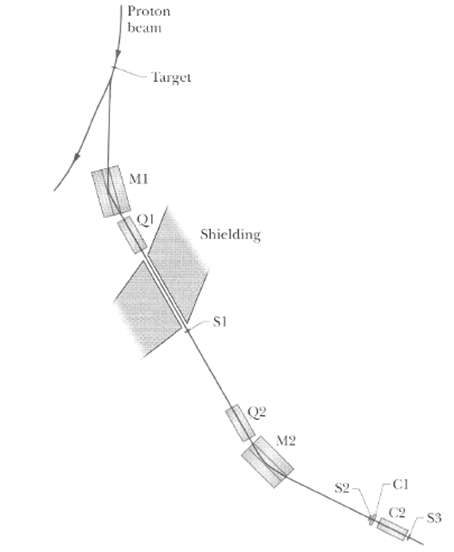

Figure shows part of the experimental arrangement in which antiprotons were discovered in the 1950s. A beam

Question:

Figure shows part of the experimental arrangement in which antiprotons were discovered in the 1950s. A beam of 6.2 GeV protons emerged from a particle accelerator and collided with nuclei in a copper target. According to theoretical predictions at the time, collisions between protons in the beam and the protons and neutrons in those nuclei should produce antiprotons via the reactions p + p ?? p + p + p + p and p + n ?? p + n + p + p However, even if these reactions did occur, they would be rare compared to the reactions p + p ?? p + p + π+ + π- and p + n ?? p + n + π+ + π-, thus, most of the particles produced by the collisions between the 6.2 GeV protons and the copper target were pions. To prove that antiprotons exist and were produced by some limited number of the collisions, particles leaving the target were sent into a series of magnetic fields and detectors as shown in Figure. The first magnetic field (M1) curved the path of any charged particle passing through it; moreover, the field was arranged so that the only particles that emerged from it to reach the second magnetic field (O1) had to be negatively charged (either a p or a π-) and have a momentum of 1.19 GeV/c π-. Field Q1 was a special type of magnetic field (a quadrapole field) that focused the particles reaching it into a beam, allowing them to pass through a hole in thick shielding to a scintillation counter 51. The passage of a charged particle through the counter triggered a signal, with each signal indicating the passage of either a 1.19 GeV/c n- or (presumably) a1.19 GeV/c p. After being refocused by magnetic field Q2 the particles were directed by magnetic field MZ through a second scintillation counter 52 and then through two Cerenkov counters Cl and C2. These latter detectors can be manufactured so that they send a signal only when the particle passing through them is moving with a speed that falls within a certain range. In the experiment, a particle with a speed greater than 0.79c would trigger C1 and a particle with a speed between 0.75c and 0.78c would trigger C2. There were then two ways to distinguish the predicted rare antiprotons from the abundant negative pions. Both ways involved the fact that the speed of a 1.19 GeV/c p differs from that of a 1.19 GeV/c π-: (1) According to calculations, a p would trigger one of the Cerenkov counters and a π- would trigger the other. (2) The time interval Δ t between signals from S1 and S2, which were separated by 12m, would have one value for a p and another value for a n. Thus, if the correct Cerenkov counter was triggered and the time interval Δ t had the correct value, the experiment would prove the existence of antiprotons. What is the speed of?

(a) An antiproton with a momentum of 1.19 GeV/c and

(b) A negative pion with that same momentum? (The speed of an antiproton through the Cerenkov detectors would actually be slightly less than calculated here because the antiproton would lose a little energy within the detectors.) Which Cerenkov detector was triggered by

(c) An antiproton and

(d) A negative pion? What time interval Ar indicated the passage of

(e) An antiproton and

(f) A negative pion? [Problem adapted from O. Chamberlain, E. Segrb, C. Wiegand, and T. Ypsilantis, "Observation of Antiprotons," Physical Revier,v, Vol. 100, pp.947 -950 (1955).]

Step by Step Answer:

Fundamentals of Physics

ISBN: 978-0471758013

8th Extended edition

Authors: Jearl Walker, Halliday Resnick