Automotive Component CorporationActivity-Based Costing Case (Prepared by Trey Johnston, Lehigh University) Automotive Component Corporation (ACC) began in

Question:

Automotive Component Corporation—Activity-Based Costing Case

(Prepared by Trey Johnston, Lehigh University)

Automotive Component Corporation (ACC)

began in 1955 as a small machine shop supplying the Big Three automakers. The business is now a $2 billion component manufacturing firm. During the three decades from 1955 to 1985, ACC expanded from a common machine shop to a modern manufacturing operation with CNC machines, automatic guided vehicles (AGVs), and a world-class quality program. Consequently, ACC’s direct-labor cost component has decreased significantly since 1955 from 46 percent to 11 percent. ACC’s current cost structure is as follows:

Manufacturing overhead 43.6%

Materials 27.1%

Selling and administrative 17.8%

expenses Labor 11.5%

Despite efforts to expand, revenues leveled off and margins declined in the late 1980s and early 1990s. ACC began to question its investment in the latest flexible equipment and even considered scrapping some. Bill Brown, ACC’s controller, explains.

“At ACC, we have made a concerted effort to keep up with current technology. We invested in CNC machines to reduce setup time and setup labor and to improve quality. Although we accomplished these objectives, they did not translate to our bottom line. Another investment we made was in AGVs. Our opinion at the time was that the reduction in labor and increased accuracy of the AGVs combined with the CNC machines would allow us to be competitive on the increasing number of small-volume orders. We have achieved success in this area, but once again, we have not been able to show a financial benefit from these programs. Recently, there has been talk of scrapping the newer equipment and returning to our manufacturing practices of the early eighties. I just don’t believe this could be the right answer but, as our margins continue to dwindle, it becomes harder and harder to defend my position.”

“At ACC, we have made a concerted effort to keep up with current technology. We invested in CNC machines to reduce setup time and setup labor and to improve quality. Although we accomplished these objectives, they did not translate to our bottom line. Another investment we made was in AGVs. Our opinion at the time was that the reduction in labor and increased accuracy of the AGVs combined with the CNC machines would allow us to be competitive on the increasing number of small-volume orders. We have achieved success in this area, but once again, we have not been able to show a financial benefit from these programs. Recently, there has been talk of scrapping the newer equipment and returning to our manufacturing practices of the early eighties. I just don’t believe this could be the right answer but, as our margins continue to dwindle, it becomes harder and harder to defend my position.”

With these sentiments in mind, Bill decided to study the current costing system at ACC in detail. He had attended a seminar recently that discussed some of the problems that arise in traditional cost accounting systems. Bill felt that some of the issues discussed in the meeting directly applied to ACC’s situation.

The speaker mentioned that ABC was a tool that corporations could use to better identify their true product costs. He also mentioned that better strategic decisions could be made based on the information provided from the activity-based reports. Bill decided to form an ABC team to look at the prospect of implementing ABC at ACC. The team consisted of two other members: Sally Summers, a product engineer with a finance background, and Jim Schmidt, an industrial engineer with an MBA.

The speaker mentioned that ABC was a tool that corporations could use to better identify their true product costs. He also mentioned that better strategic decisions could be made based on the information provided from the activity-based reports. Bill decided to form an ABC team to look at the prospect of implementing ABC at ACC. The team consisted of two other members: Sally Summers, a product engineer with a finance background, and Jim Schmidt, an industrial engineer with an MBA.

Sally had some feelings about the current state of ACC:

“ACC is a very customer-focused company.

When the automakers demanded small-volume orders, we did what we could to change our manufacturing processes. The problem is that no one realized that it takes just as long for the engineering department to design a 10-component part and process for a smallvolume order as it does for a 10-component, large-volume order. Our engineering departments cannot handle this kind of workload much longer. On top of this, we hear rumors about layoffs in the not-too-distant future.”

Jim felt similarly:

“Sally is correct. As an industrial engineer, I get involved in certain aspects of production that are simply not volume dependent. For example, I oversee first-run inspections. We run a predetermined number of parts before each full run to ensure the process is under control. Most of the inspections we perform on the automobile components are looking for burrs, which can severely affect fit or function downstream in our assembly process.

Many times, we can inspect sample part runs right on the line. The real consumption of resources comes from running a sample batch, not by inspecting each part.”

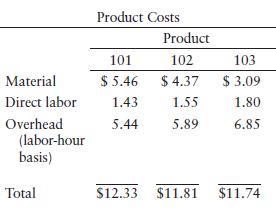

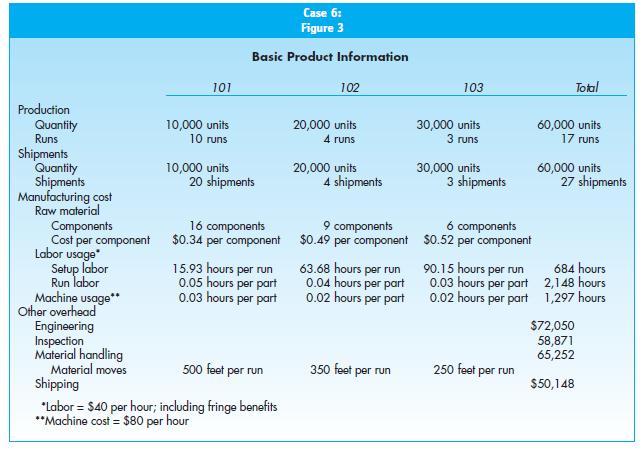

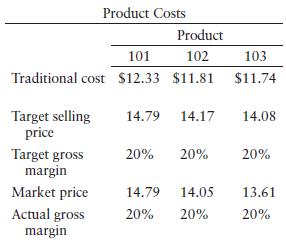

To begin its study, the team obtained a cost report from the plant’s cost accountant. A summary of the product costs is as follows:

ACC has been determining product costs basically the same way it did in 1955. Raw material cost is determined by multiplying the number of components by the standard raw material price. Direct labor cost is determined by multiplying the standard labor hours per unit by the standard labor rate per hour.

Manufacturing overhead is allocated to product based on direct labor content.

The team then applied the traditional 20 percent markup to the three products. This represents the target price that ACC tries to achieve on its products. They then compared the target price to the market price. ACC was achieving its 20 percent target gross margin on Product 101, but not on Products 102 or 103, as illustrated below.

The team then applied the traditional 20 percent markup to the three products. This represents the target price that ACC tries to achieve on its products. They then compared the target price to the market price. ACC was achieving its 20 percent target gross margin on Product 101, but not on Products 102 or 103, as illustrated below.

Bill was concerned; he remembered the conference he had attended. The speaker had mentioned examples of firms headed in a downward spiral because of a faulty cost system.

Bill asked the team, “Is ACC beginning to show signs of a faulty cost system?”

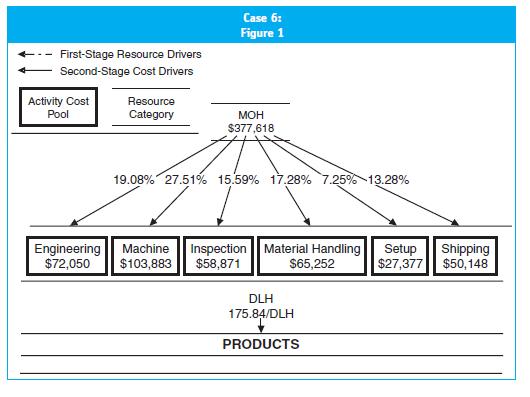

Next, the team looked at the manufacturing overhead breakdown (Figure 1). The current cost accounting system allocated 100 percent of this overhead to product based on labor dollars. The team felt ACC could do a better job of tracing costs to products based on transaction volume. Jim explains:

“The manufacturing overhead really consists of the six cost pools shown in Figure 1.

Each of these activity cost pools should be traced individually to products based on the proportion of transactions they consume, not the amount of direct labor they consume.”

The team conducted the following interviews to determine the specific transactions ACC should use to trace costs from activities to products.

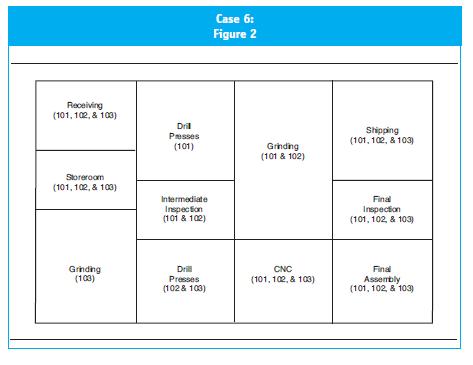

John “Bull” Adams, the supervisor in charge of material movement, provided the floor layout shown in Figure 2 and commented on his department’s workload:

“Since ACC began accepting small-volume orders, we have had our hands full. Each time we design a new part, a new program must be written. Additionally, it seems the new smallvolume parts we are producing are much more complex than the large-volume parts we produced just a few years ago. This translates into more moves per run. Consequently, we wind up performing AGV maintenance much more frequently.

Sometimes I wish we would get rid of those AGVs; our old system of forklifts and operators was much less resistant to change.”

Sara Nightingale, the most experienced jobsetter at ACC, spoke about the current status of setups:

“The changeover crew has changed drastically recently. Our team has shifted from mostly mechanically skilled maintenance people to a team of highly trained programmers and mechanically skilled people. This shift has greatly reduced our head count.

Yet the majority of our work is still spent on setup labor time.”

Phil Johnson, the shipping supervisor, told the team what he felt drove the activity of the shipping department:

“The volume of work we have at the shipping department is completely dependent on the number of trucks we load. Recently, we have been filling more trucks per day with less volume. Our workload has increased, not decreased. We still have to deal with all of the paperwork and administrative hassles for each shipment. Also, the smaller trucks they use these days are side-loaders, and our loading docks are not set up to handle these trucks. Therefore, it takes us a while to coordinate our docks.”

Once the interviews were complete, the team went to the systems department to request basic product information on the three products ACC manufactured. The information is shown in Figure 3.

Required:

The team has conducted all of the required interviews and collected all of the necessary information in order to proceed with its ABC pilot study.

a. The first three steps in an activity-based cost implementation are to define the resource categories, activity centers, and first-stage resource drivers. These steps have already been completed at ACC, and the results are displayed in Figure 1.

Using the information from the case, perform the next step for the implementation team and determine the second-stage cost drivers ACC should use in its ABC system. Support your choices with discussion.

b. Using the second-stage cost drivers identified in part (a), compute the new product costs for Products 101, 102, and 103.

c. Modify Figure 2 and include the cost drivers identified in part (a).

d. Compare the product costs computed under the current cost accounting system to the product costs computed under the activity-based system.

e. Explain the differences in product cost.

f. Given the new information provided by the ABC system, recommend a strategy ACC should pursue to regain its margins, and comment on specific improvements that would reduce ACC’s overhead burden in the long run.

Step by Step Answer: