Enron Corporation entered 2001 as the seventh largest public company in the United States only to later

Question:

Enron Corporation entered 2001 as the seventh largest public company in the United States only to later exit the year as the largest company to ever declare bankruptcy in U.S history. Although investigations into the company's demise will likely continue for years, reasons for Enron's collapse are already becoming clear. Investors who lost millions and lawmakers seeking to prevent similar reoccurrences are stunned by these unbelievable events. The following testimony of Rep. Richard H. Baker, chair of the House Capital Markets Subcommittee, exemplifies these feelings:

We are here today to examine and begin the process of understanding the most stunning business reversal in recent history.

One moment an international corporation with a diversified portfolio enjoying incredible run-up of stock prices, the darling of financial press and analysts, which, by the way, contributed to the view that Enron had indeed become the new model for business of the future, indeed, a new paradigm. One edition of Fortune magazine called it the best place in America for an employee to work. Analysts gave increasingly creative praise, while stock prices soared.... Now in retrospect, it is clear, at least to me, that while Enron executives were having fun, it actually became a very large hedge fund, which just happened to own a power company. While that in itself does not warrant criticism, it was the extraordinary risk taking by powerful executives which rarely added value but simply accelerated the cash burn-off rate. Executives having Enron fun are apparently very costly and, all the while, they were aggressive in the exercise of their own [Enron] stock options, flipping acquisitions for quick sale. One executive sold a total of \(\$ 353\) million in the 3 -year period preceding the failure. What did he know? When did he know it? And why didn't we? \({ }^{1}\)

Although company executives may have been involved in questionable business practices even bordering on fraud, Enron's failure was ultimately due to a collapse of investor, customer, and trading partner confidence. In the boom years of the late 1990's, Enron entered into a number of aggressive transactions involving "special purpose entities" (SPE's) for which the underlying accounting was questionable. Some of these transactions essentially involved Enron receiving borrowed funds that were made to look like revenues, without recording liabilities on the company's balance sheet. The "loans" were guaranteed with Enron stock, trading at over \(\$ 100\) per share at the time. When the transaction deals went sour simultaneous with massive drops in Enron's stock price, the company was in trouble. Debtholders began to recall the loans due to Enron's diminished stock price, and the company found its accounting positions increasingly problematic to maintain. Then, the August 2001 resignation of Enron's chief executive officer (CEO), Jeffrey Skilling, only six months after beginning his "dream job" further fueled Wall Street skepticism and scrutiny over company operations. Shortly thereafter, The Wall Street Journal's "Heard on the Street" column of August 28, 2001 drew further attention to the company, igniting a public firestorm of controversy that quickly led to the company's loss of reputation and trust. The subsequent loss of confidence by trading partners and customers quickly dried up Enron's trading volume, and the company found itself facing a liquidity crisis by late 2001 .

Jeffery Skilling, former CEO, summed it up this way when he testified before the House Energy Commerce Committee on February 7, 2002:

It is my belief that Enron's failure was due to a classic 'run on the bank:' a liquidity crisis spurred by a lack of confidence in the company. At the time of Enron's collapse, the company was solvent and highly profitable - but, apparently, not liquid enough. That is my view of the principal cause of its failure. \({ }^{2}\)

Public disclosure of diminishing liquidity and questionable management decisions and practices destroyed the trust Enron had established within the business community. This caused hundreds of trading partners, clients and suppliers to halt doing business with the company, ultimately leading to its downfall.

Enron's collapse, along with events related to the audits of Enron's financial statements, caused a similar loss of reputation, trust, and confidence in Big-5 accounting firm, Andersen, LLP. Enron's collapse and the associated revelations of alleged aggressive and inappropriate accounting practices caused major damage for this international firm. But, news about charges of inappropriate destruction of documents at the Andersen office in Houston, which was in charge of the Enron audit, and the subsequent unprecedented federal indictment was the kiss of death for this former Big-5 accounting firm. As with Enron, Andersen's clients quickly lost confidence, and by June 2002, more than 400 of its largest clients had fired the firm as their auditor, leading to the sale or desertion of various pieces of Andersen's U.S. and international practices. On June \(15^{\text {th }}\), a federal Houston jury convicted Andersen on one felony count of obstructing the SEC's investigation into Enron's collapse. After the verdict, Andersen announced it would cease auditing publicly owned clients by August 31, 2002. Thus like Enron, in an astonishingly short period of time, Andersen went from being one of the world's largest and most respected professional services firms, to an embattled, dwindled shadow of its former self, winding down its operations.

Despite inclusion in the Fortune 500, few people outside of Texas had heard of Enron prior to its fall and the subsequent Congressional investigation. However, because of the Congressional hearings and intense media coverage, along with the tremendous impact the company's collapse has had on the corporate community and accounting profession, the name "Enron" will reverberate for many years to come. Here's a brief analysis of the complex fall of these two giants.

ENRON IN THE BEGINNING

Enron Corporation, based in Houston, Texas, was formed as the result of the July 1985 merger of Houston Natural Gas and InterNorth of Omaha, Nebraska. In its early years, Enron was a natural gas pipeline company whose primary business strategy involved entering into contracts to deliver specified amounts of natural gas to businesses or utilities over a given period of time. In 1989, Enron began trading natural gas commodities. With the deregulation of the electrical power markets in the early 1990s-a change for which senior Enron officials lobbied heavily-Enron swiftly evolved from a conventional business that simply delivered energy into a "new economy" business heavily involved in the brokerage of speculative energy futures. Enron acted as an intermediary by entering into contracts with buyers and sellers of energy, profiting on the price difference. Enron began marketing electricity in the U.S. in 1994, and entered the European energy market in 1995.

At the height of the Internet boom, Enron furthered its transformation into a "new economy" company by launching EnronOnline, a Web-based commodity trading site, in 1999. Enron also broadened its technological reach by entering the business of buying and selling access to high-speed Internet bandwidth. At its peak, Enron owned a stake in nearly 30,000 miles of gas pipelines, owned or had access to a 15,000 -mile fiber optic network, and had a stake in several electricity-generating operations around the world. In 2000, the company reported gross revenues of \(\$ 101\) billion.

Enron continued to expand its business into extremely complex ventures by offering a wide variety of financial hedges and contracts to customers. These financial instruments were designed to protect customers against a variety of risks, including events such as changes in interest rates and changes in the weather. The volume of transactions involving these "new economy" type instruments grew rapidly and actually surpassed the volume of traditional contracts involving delivery of physical commodities, such as natural gas to customers. To ensure that Enron managed the risks related to these "new economy" instruments, the company hired a large number of employees who were experts in the fields of mathematics, physics, meteorology, and economics. \({ }^{3}\)

Within a year of its launch, EnronOnline was handling more than \(\$ 1\) billion in transactions a day. The web site was much more than a place for buyers and sellers of various commodities to meet. Internetweek reported that, "It was the market, a place where everyone in the gas and power industries gathered pricing data for virtually every deal they made, regardless of whether they executed them on the site. "4 The site's success depended on cutting-edge technology and more importantly on the trust the company developed with its customers and partners who expected Enron to follow through on its price and delivery promises.

When the company's accounting shenanigans were brought to light, customers, investors, and other partners ceased trading through the energy giant when they lost confidence in Enron's ability to fulfill its obligations and act with integrity in the marketplace. \({ }^{5}\)

ENRON'S COLLAPSE

On August 14, 2001, Kenneth Lay was reinstated as Enron's CEO after Jeffery Skilling resigned for "purely personal" reasons after having only served for a sixmonth period as CEO. Skilling joined Enron in 1990 after leading McKinsey \& Company's energy and chemical consulting practice, and became Enron's president and chief operating officer in 1996. Skilling was appointed CEO in early 2001 to replace Lay who had served as chairman and CEO since 1986. \({ }^{6}\)

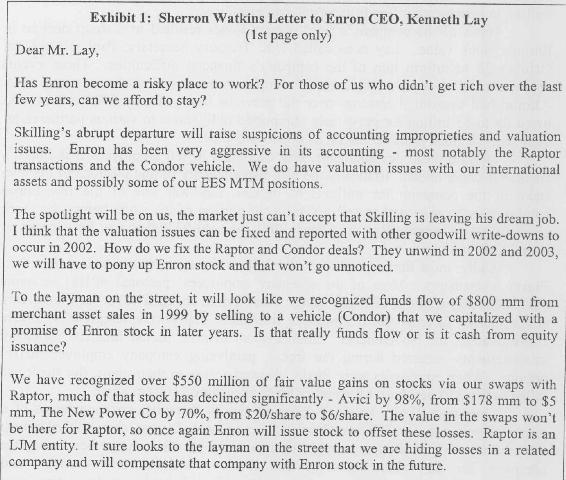

Skilling's resignation would prove to be the beginning of Enron's collapse. The day after Skilling resigned, Enron vice president of corporate development, Sherron Watkins, sent an anonymous letter to Kenneth Lay (see Exhibit 1). In the letter, she detailed her fears that Enron "might implode in a wave of accounting scandals." The letter later branded her as a loyal employee trying to save the company through her whistle-blowing efforts.

Two months later, Enron reported a 2001 third quarter loss of \(\$ 618\) million and a reduction of \(\$ 1.2\) billion in shareholder's equity related to partnerships run by chief financial officer (CFO), Andrew Fastow. Fastow had created and managed numerous off-the-balance-sheet partnerships for Enron, which also benefited him personally. In fact, during his tenure at Enron, Fastow collected approximately \(\$ 30\) million in management fees from various partnerships.

News of the company's third quarter losses resulted in a sharp decline in Enron's stock value. Lay even called U.S. Treasury Secretary, Paul O'Neill, on October 28 to inform him of the company's financial difficulties. Those events where then followed by a November \(8^{\text {th }}\) company announcement of even worse news - Enron had overstated earnings over the previous four years by \(\$ 586\) million and owed up to \(\$ 3\) billion for previously unreported obligations to various partnerships. That sent the stock price further on its downward slide.

Despite these developments, Lay continued to tell employees that Enron's stock was undervalued. Ironically, he was also allegedly selling portions of his own stake in the company for millions of dollars. Lay was one of the few Enron employees who managed to sell a significant portion of his stock before the stock price collapsed completely. In August 2001, he sold 93,000 shares for a profit of over \(\$ 2\) million.

Sadly, most Enron employees didn't have the same chance to liquidate their Enron investments. Most of the company employees' personal \(401(\mathrm{k})\) accounts contained large amounts of Enron stock. When Enron changed 401(k) administrators at the end of October 2001, employee retirement plans were temporarily frozen. Unfortunately, the November \(8^{\text {th }}\) announcement of prior period financial statement misstatements occurred during the freeze, paralyzing company employee \(401(\mathrm{k})\) options. When employees were finally allowed access to their plans, the stock had fallen below \(\$ 10\) per share from earlier highs exceeding \(\$ 100\) per share.

Corporate "white knights" appeared shortly thereafter spurring hopes of a rescue. Dynegy Inc. and ChevronTexaco Corp. (a major Dynegy shareholder) almost spared Enron from bankruptcy when they announced a tentative agreement to buy the company for \(\$ 8\) billion in cash and stock. Unfortunately, Dynegy and ChevronTexaco later withdrew their offer after Enron's credit rating was downgraded to "junk" status in late November. Enron tried unsuccessfully to prevent the downgrade, and allegedly asked the Bush administration for help in the process.

After Dynegy formally rescinded its purchase offer, Enron filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy on December 2, 2001. This announcement eventually forced the company's stock price to a low of \(\$ 0.40\) per share. On January 15, 2002, the New York Stock Exchange suspended trading in Enron's stock and began the process to formally de-list it.

It is important to understand that most of the earnings restatements may not technically have been attributable to improper accounting treatment in the periods since 1997. So, what made these enormous restatements necessary? In the end, the decline in Enron's stock price triggered contractual obligations that were never reported on the balance sheet due to "loopholes" in accounting standards that Enron exploited. An analysis of the nuances of Enron's partnership accounting provides some insight as to the unraveling of this major corporate giant.

Unraveling the "Special Purpose Entity" Web. The term "special purpose entity" (SPE) has become synonymous with the Enron collapse because these entities were at the center of Enron's aggressive business and accounting practices. SPE's are separate legal entities set up to accomplish specific company objectives. For example, SPE's are often created to help a company sell off assets. After identifying which assets to sell to the SPE, the selling company secures an outside investment of at least three percent of the value of the assets to be sold to the SPE? The company then transfers the identified assets to the SPE. The SPE pays for the contributed assets through a new debt or equity issuance. The selling company can then recognize the sale of the assets to the SPE and thereby remove the assets and any related debts from its balance sheet. This is all contingent on the outside investors bearing the risk of their investment. In other words, they cannot finance their interest through a note payable or other type of guarantee that may absolve them from accepting responsibility if the SPE suffers losses or fails. 8 While SPE's are commonplace in corporate America, they are controversial. Some argue that SPE's represent a "gaping loophole in accounting practice." \({ }^{9}\) Tradition dictates that once a company owns \(50 \%\) or more of another, the company must consolidate. However, as the following quote from Business Week demonstrates such is not the case with SPE's:

The controversial exception that outsiders need invest only three percent of an SPE's capital for it to be independent and off the balance sheet came about through fumbles by the Securities \& Exchange Commission and the Financial Accounting Standards Board. In 1990, accounting firms asked the SEC to endorse the three percent rule that had become a common, though unofficial, practice in the '80s. The SEC didn't like the idea, but it didn't stomp on it, either. It asked the FASB to set tighter rules to force consolidation of entities that were effectively controlled by companies. FASB drafted two overhauls of the rules but never finished the job, and the SEC is still waiting. \({ }^{10}\)

While SPE's can serve legitimate business purposes, it is now apparent that Enron used an intricate network of SPE's, along with complicated speculations and hedges-all couched in dense legal language - to keep an enormous amount of debt off the company's balance sheet. Enron had literally hundreds of SPE's. Through careful structuring of these SPE's that took into account the complex accounting rules governing the required financial statement treatment of SPE's (e.g., FAS 140), Enron was able to avoid consolidating the SPE's on its balance sheet. Three of the Enron SPE's have been made prominent throughout the congressional hearings and litigation proceedings. These are widely known as "Chewco," "LJM2," and "Whitewing."

Chewco was established in 1997 by Enron executives in connection with a complex investment in another Enron partnership with interests in natural gas pipelines. Enron's CFO, Andrew Fastow, was charged with managing the partnership. However, to prevent required disclosure of a potential conflict of interest between Fastow's roles at Enron and Chewco, Fastow employed Michael Kopper, managing director of Enron Global Finance, to "officially" manage Chewco. In connection with the Chewco partnership, Fastow and Kopper appointed Fastow relatives to the board of directors of the partnership. Then, in a set of complicated transactions, another layer of partnerships was established to disguise Kopper's invested interest in Chewco. Kopper originally invested \(\$ 125,000\) in Chewco and was later paid \(\$ 10.5\) million when Enron bought Chewco in March 2001. \({ }^{11}\) Surprisingly, Kopper remained relatively unknown throughout the subsequent investigations. In fact, Ken Lay told investigators that he didn't know Kopper. Kopper was able to continue in his management roles up until January 2002. \({ }^{12}\)

The LJM2 partnership was formed in October 1999 with the goal of acquiring assets chiefly owned by Enron. Like Chewco, LJM2 was managed by Fastow and Kopper. To assist with the technicalities of this partnership, LJM2 engaged the accounting firm, PricewaterhouseCoopers, LLP and the Chicago-based law firm, Kirkland \& Ellis, where Whitewater prosecutor Kenneth Star serves as partner. Enron used the LJM2 partnership to deconsolidate its less productive assets. Eventually, these actions generated a 30 percent average annual return for the LJM2 limited-partner investors.

The Whitewing partnership, another significant SPE established by Enron, engaged in purchasing an assortment of power plants, pipelines, and water projects originally purchased by Enron in the mid-1990s that were located in India, Turkey, Spain, and Latin America. The Whitewing partnership was crucial to Enron's move from being an energy provider to becoming a trader of energy contracts. Whitewing was the vehicle through which Enron sold its energy production assets.

In creating this partnership, Enron quietly guaranteed investors in Whitewing that if Whitewing's assets (transferred from Enron) were sold at a loss, Enron would compensate the investors with shares of Enron common stock. This obligationunknown to Enron's shareholders-totaled \(\$ 2\) billion as of November 2001. Part of the secret guarantee to Whitewing investors surfaced in October 2001, when Enron's credit rating was downgraded by credit agencies. The credit downgrade triggered a requirement that Enron immediately pay \(\$ 690\) million to Whitewing investors. When this obligation surfaced, Enron's talks with Dynegy to sell the company failed. Enron was unable to delay the payment and was forced to disclose the problem, stunning investors and fueling the fire that led to the company's bankruptcy filing on December 2, 2001.

In addition to these partnerships, Enron created financial instruments called "Raptors," which were designed to reduce the risks associated with Enron's own investment portfolio and backed by Enron stock. In essence, the Raptors covered potential losses on Enron investments as long as Enron's stock market price continued to do well. Enron also masked debt using complex financial derivative transactions. Taking advantage of accounting rules to account for large loans from Wall Street firms as financial hedges, Enron hid \$3.9 billion in debt from 1992 through 2001. At least \(\$ 2.5\) billion of those transactions arose in the three years prior to the Chapter 11 bankruptcy filing. These loans were in addition to the \(\$ 8\) to \(\$ 10\) billion in long and short-term debt that Enron disclosed in its financial reports in the three years leading up to its bankruptcy. Because the loans were accounted for as a hedging activity, Enron was able to explain away what looked like an increase in borrowings, (which would raise red flags for creditors), as hedges for commodity trades, rather than new debt financing. \({ }^{13}\)

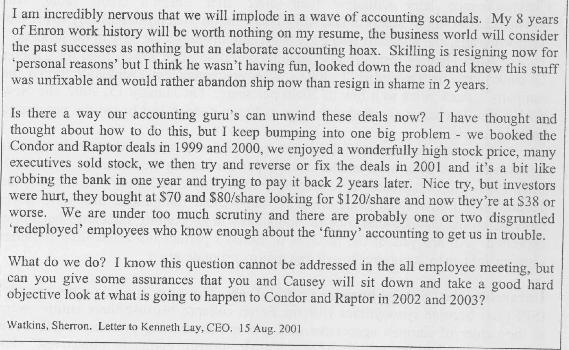

The Complicity of Accounting Standards. Limitations in generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP) are at least partly to blame for Enron executives' ability to hide debt from the company's financial statements. These technical accounting standards lay out specific "bright-line" rules that read much like the tax or criminal law codes. Some observers of the profession argue that by attempting to outline every accounting situation in detail, standard-setters are trying to create a specific decision model for every imaginable situation. However, very specific rules create an opportunity for clever lawyers, investment bankers, and accountants to create entities and transactions that circumvent the intent of the rules while still conforming to the "letter of the law."

In his congressional testimony, Robert K. Herdman, SEC Chief Accountant, discussed the difference between rule and principle-based accounting standards:

\begin{abstract}

Rule-based accounting standards provide extremely detailed rules that attempt to contemplate virtually every application of the standard. This encourages a check-the-box mentality to financial reporting that eliminates judgments from the application of the reporting. Examples of rule-based accounting guidance include the accounting for derivatives, employee stock options, and leasing. And, of course, questions keep coming. Rule-based standards make it more difficult for preparers and auditors to step back and evaluate whether the overall impact is consistent with the objectives of the standard. \({ }^{14}\)

\end{abstract}

While the specifics are still under investigation, in some cases it appears that Enron neither abode by the spirit nor the letter of these accounting rules (for example, by securing outside SPE investors against possible losses). It also appears that the company's lack of disclosure regarding Fastow's involvement in the SPE's fell short of accounting rule compliance.

These "loopholes" allowed Enron executives to hide many of the company's liabilities from the financial statements being auditing by Andersen, LLP, as highlighted by the Business Week article summarized in Exhibit 2. Given the alleged abuse of the accounting rules, many are asking, "Where was Andersen, the accounting firm that was to serve as Enron's public 'watchdog,' while Enron allegedly betrayed and misled its shareholders?"

It is clear that investors and the public believe that Enron executives are not the only parties responsible for the company's collapse. Many fingers are also pointing to Enron's auditor, Andersen, LLP, which issued "clean" audit opinions on Enron's financial statements from 1997 to 2000 but later agreed that a massive earnings restatement was warranted. Andersen's involvement with Enron has decimated the accounting firm-something the global business community would have thought impossible in the fall of 2001. Ironically, Andersen may cease to exist for the same reasons Enron failed-the company lost the trust of its clients and other business partners.

Andersen in the Beginning. Andersen was originally founded as Andersen, Delaney \& Co. in 1913 by Arthur Andersen, an accounting professor at Northwestern University in Chicago. By taking tough stands against clients, Andersen quickly gained a national reputation as a reliable keeper of the public's trust:

In 1915, Andersen took the position that the balance sheet of a steamship-company client had to reflect the costs associated with the sinking of a freighter, even though the sinking occurred after the company's fiscal year had ended but before Andersen had signed off on its financial statements. This marked the first time an auditor had demanded such a degree of disclosure to ensure accurate reporting.

Although Andersen's storied reputation began with its founder, the accounting firm continued the tradition for years. A phrase often said around Andersen was, "There's the Andersen way and the wrong way." Andersen was the only one of the major accounting firms to back reforms in the accounting for pensions in the 1980 s, a move opposed by many corporations. \({ }^{16}\) Ironically, prior to the Enron debacle, Andersen had also previously taken an unpopular public stand to toughen the very accounting standards that Enron exploited in using SPE's to keep debt off its balance sheets.

Andersen's Loss of Reputation. Prior to the Enron disaster, Andersen's reputation suffered largely because of the number of high profile SEC investigations launched against the firm. The firm was investigated for its role in the financial statement audits of Waste Management, Global Crossing, Sunbeam, Qwest Communications, Baptist Foundation of Arizona, and WorldCom. In May 2001, Andersen paid \(\$ 110\) million to settle securities fraud charges stemming from its work at Sunbeam. In June 2001, Andersen entered a no-fault, no-admission-of-guilt plea bargain with the SEC to settle charges of Andersen's audit work on Waste Management, Inc. for \(\$ 7\) million. Andersen later settled with investors of the Baptist Foundation of Arizona for \(\$ 217\) million without admitting fault or guilt (the firm subsequently reneged on the agreement). Due to this string of negative events and associated publicity, Andersen found its once-applauded reputation for impeccable integrity questioned by a market where integrity, independence, and reputation are the primary attributes affecting demand for the firm's services.

Andersen at Enron. By 2001 Enron had become one of Andersen's largest clients. Despite the recognition that Enron was a high-risk client, Andersen apparently had difficulty sticking to its guns at Enron:

[Andersen had] found \(\$ 51\) million of problems in the company's books - and decided to let them go uncorrected. While auditing Enron's 1997 financial results, Andersen proposed that the energy company make 'adjustments' that would have cut its annual income by almost 50 percent, to \(\$ 54\) million from \(\$ 105\) million..... Enron chose not to make those adjustments and Andersen put its stamp of approval on the company's financial report anyway. \({ }^{17}\)

Andersen chief executive, Joseph F. Berardino, testified before the U.S. Congress that, after proposing the \(\$ 51\) million of adjustments to Enron's 1997 results, the accounting firm decided that those adjustments were not material. \({ }^{18}\) Congressional hearings and the business press allege that Andersen was unable to stand up to Enron because of the conflicts of interest that existed due to large fees and the mix of services Andersen provided to Enron.

In 2000 Enron reported that it paid Andersen \(\$ 52\) million, \(\$ 25\) million for the financial statement audit work and \(\$ 27\) million for consulting services. Andersen not only performed the external financial statement audit, but also carried out Enron's internal audit functions, a common practice in the accounting profession before the Enron debacle. Ironically, Enron's 2000 annual report disclosed that one of the major projects Andersen performed in 2000 was to examine and report on management's assertion about the effectiveness of Enron's system of internal controls.

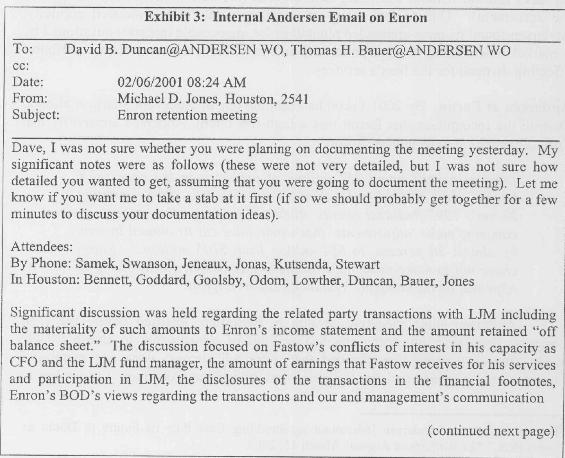

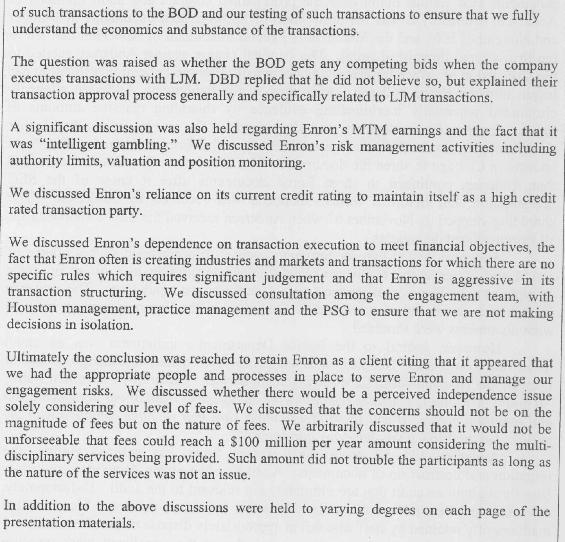

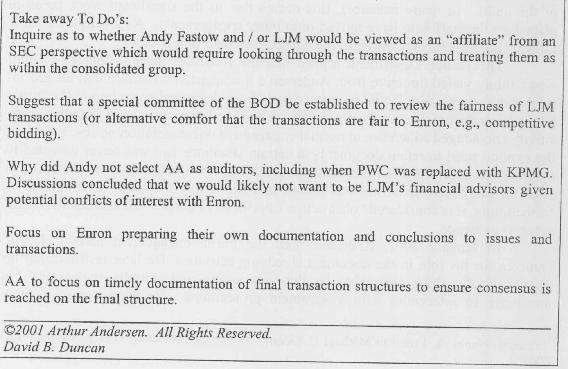

Comments by investment billionaire, Warren E. Buffett, summarize the perceived conflict that often arises when auditors receive significant fees from audit clients: "Though auditors should regard the investing public as their client, they tend to kowtow instead to the managers who choose them and dole out their pay. "Buffett continued by quoting an old proverb: "Whose bread I eat, his song I sing. "19 It also appears that Andersen knew about Enron's problems nearly a year before the downfall. According to a February 6, 2001 internal firm e-mail, Andersen considered dropping Enron as a client. The e-mail, which was written by an Andersen partner to David Duncan, partner in charge of the Enron audit, detailed the discussion at an Andersen meeting about the future of the Enron engagement. The essential text of that email is reproduced in Exhibit 3.

The Andersen Indictment. Although the massive restatements of Enron's financial statements cast serious doubt over the professional conduct and audit opinions of Andersen, ultimately it was the destruction of Enron-related documents in October and November 2001 and the March 2002 Federal indictment of Andersen that led to the firm's rapid downward spiral. The criminal charge against Andersen related to the obstruction of justice for destroying documents after the Federal investigation had begun into the Enron collapse. According to the indictment, Andersen allegedly eliminated potentially incriminating evidence by shredding massive amounts of Enron-related audit workpapers and documents. The government alleged that Andersen partners in Houston were directed by the firm's national office legal counsel in Chicago to shred the documents. The U.S. Justice Department contended that Andersen continued to shred Enron documents after it knew of the SEC investigation, but before a formal subpoena was received by Andersen. The shredding stopped on November \(8^{\text {th }}\) when Andersen received the SEC's subpoena for all Enron-related documents.

Andersen denied that its corporate counsel recommended such a course of action and assigned the blame for the document destruction to a group of rogue employees in its Houston office seeking to save their own reputations. The evidence is unclear as to exactly who ordered the shredding of the Enron documents or even what documents were shredded.

However, central to the Justice Department's indictment was an email forwarded from Nancy Temple, Andersen's corporate counsel in Chicago, to David Duncan, the Houston-based Enron engagement partner. The body of the email states, "It might be useful to consider reminding the engagement team of our documentation and retention policy. It will be helpful to make sure that we have complied with the policy. Let me know if you have any questions. \({ }^{\text {20 }}\)

Andersen, like all professional service firms, has policies guiding the retention and destruction of documents. Auditors often obtain documents and other files throughout an audit that are ultimately not relevant to the audit. Unfortunately, a common problem in the audit profession is that these documents and files are often inadvertently retained by staff who fail to appropriately dispose of the files at the end of the audit. In many instances, this occurs due to the significant work pressure placed on the staff who have moved onto other engagements. As a result, the staff fails to take the time to dispose of the unused files on a timely basis.

The Justice Department argued that the Andersen general counsel's email was a thinly veiled directive from Andersen's headquarters to ensure that all Enronrelated documents that should have previously been destroyed according to the firm's policy were destroyed. Andersen contended that the infamous Nancy Temple memo simply encouraged adherence to normal engagement documentation policy, including the explicit need to retain documents in certain situations and was never intended to obstruct the government's investigation. However, it is important to understand that once an individual or a firm has reason to believe that a federal investigation is forthcoming, it is considered "obstruction of justice" to destroy documents that might serve as evidence.

In January 2002, Andersen fired the Enron engagement partner, David Duncan, for his role in the document shredding activities. He later testified that he didn't initially think that what he did was wrong and initially maintained his innocence in interviews with government prosecutors. He even signed a joint defense agreement with Andersen on March 20, 2002. Shortly thereafter, Duncan decided to plead guilty to obstruction of justice charges after "a lot of soul searching about my intent and what was in my head at the time." 21 In the obstruction of justice trial against Andersen, Duncan testified for the Federal prosecution, admitting that he ordered the destruction of documents because of the email he received from Andersen's counsel reminding him of the company's document retention policy. He also testified that he wanted to get rid of documents that could be used by prosecuting attorneys and SEC investigators. \({ }^{22}\)

The End of Andersen. In the early months of 2002, Andersen pursued the possibility of being acquired by one of the other four Big-5 accounting firms: PricewaterhouseCoopers, Ernst \& Young, KPMG, and Deloitte \& Touche. The most seriously considered possibility was an acquisition of the entire collection of Andersen partnerships by Deloitte \& Touche, but the talks fell through only hours before an official announcement of the acquisition was scheduled to take place. The biggest barrier to an acquisition of Andersen apparently centered around fears that an acquirer would assume Andersen's liabilities and responsibility for settling future Enron-related lawsuits.

In the aftermath of Enron's collapse, Andersen began to unravel quickly, losing over 400 publicly traded clients by June 2002-including many high-profile clients with which Andersen enjoyed long relationships. \({ }^{23}\) The list of former clients includes Delta Air Lines, FederalExpress, Merck, SunTrust Banks, Abbott Laboratories, Freddie Mac, and Valero Energy Corp. In addition to losing clients, Andersen lost many of its global practice units to rival accounting and consulting firms and agreed to sell a major portion of its consulting business to KPMG consulting for \(\$ 284\) million and agreed to sell most of its tax advisory practice to Deloitte \& Touche.

On March 26, 2002, Joseph Berardino, CEO of Andersen Worldwide, resigned as CEO, but remained with the firm. In an attempt to salvage the firm, Andersen hired former Federal Reserve chairman, Paul Volcker, to head an oversight board to make recommendations to rebuild Andersen. Mr. Volcker and the board recommended that Andersen split its consulting and auditing businesses and that he and the seven-member board take over Andersen in order to realign firm management and implement reforms. The success of the oversight board depended on Andersen's ability to stave off criminal charges and settle lawsuits related to its work on Enron. Because Andersen failed in this regard, Mr. Volcker suspended the board's efforts to rebuild Andersen in April 2002.

Andersen faced an uphill battle in its fight against the federal prosecutors' charges of a felony count for the obstruction of justice, regardless of the trial's outcome. Never in the 212 -year history of the U.S. financial system has a major financial-services firm survived a criminal indictment, and Andersen would not likely have been the first, even had the firm not been convicted of a single count of obstruction of justice on June 15, 2002. Andersen, along with many others, accused the justice department of a gross abuse of governmental power, and announced that it would appeal the conviction. However, the firm also announced that it would cease to audit publicly held clients by August 31, 2002 .

The details surrounding Enron's bankruptcy and Andersen's fall from grace will continue to be uncovered for years. Only time will tell the fate of those involved. But one thing is certain-the Enron debacle will have a profound and lasting impact on the accounting profession and on the entire business community for years to come.

REQUIREMENTS

1. What were the business risks Enron faced and how did those risks increase the likelihood of material misstatements in Enron's financial statements?

2. What are the responsibilities of a company's board of directors? Could the board of directors at Enron-especially the audit committee - have prevented the fall of Enron? Should they have known about the risks and apparent lack of independence with SPE's? What should they have done about it?

3. In your own words, summarize how Enron used SPE's to hide large amounts of company debt.

4. What are the auditor independence issues surrounding the provision of external auditing services, internal auditing services, and management consulting services for the same client? Develop arguments for why auditors should be allowed to perform these services for the same client. Develop separate arguments for why auditors should not be allowed to perform non-audit services for their audit clients.

5. Explain how "rules-based" accounting standards differ from "principles-based" standards. How might fundamentally changing accounting standards from bright-line rules to principle-based standards help prevent another Enron-like fiasco in the future? Are there dangers in removing bright-line rules? What difficulties might be associated with such a change?

6. Enron and Andersen suffered severe consequences because of their perceived lack of integrity and damaged reputations. In fact, some people believe the fall of Enron occurred because of a "run on the bank." Some argue that Andersen experienced a similar "run on the bank" as many top clients quickly fired the firm in the wake of Enron's collapse. Is the "run on the bank" analogy valid for both firms? Why or why not?

7. Why did so many companies terminate their relationships with Andersen, given that Andersen's Houston office had no part in servicing those engagements?

8. A perceived lack of integrity caused irreparable damage to both Andersen and Enron. How can you apply the principles learned in this case personally? Generate an example of how involvement in unethical or illegal activities, or even the appearance of such involvement, might adversely affect your career. What are the possible consequences when others question your integrity? What can you do to preserve your reputation throughout your career?

9. Why do audit partners struggle with making tough accounting decisions that may be contrary to their client's position on the issue? What changes should the profession make to eliminate these obstacles?

10. What has been done, and what more can be done to restore the public trust in the auditing profession and in the nation's financial reporting system?

Step by Step Answer:

Auditing Cases An Active Learning Approach

ISBN: 9781266566899

2nd Edition

Authors: Mark S. Beasley, Frank A. Buckless, Steven M. Glover, Douglas F. Prawitt