In 1969, Eddie Antar, a 21-year-old high school dropout from Brooklyn, opened a consumer electronics store with

Question:

In 1969, Eddie Antar, a 21-year-old high school dropout from Brooklyn, opened a consumer electronics store with 150 square feet of floor space in New York City. Despite this modest beginning, Antar would eventually dominate the retail consumer electronics market in the New York City metropolitan area. By 1987, Antar’s firm, Crazy Eddie, Inc., had 43 retail outlets, sales exceeding \($350\) million, and outstanding stock with a collective market value of \($600\) million. Antar personally realized more than \($70\) million from the sale of Crazy Eddie stock during his tenure as the company’s chief executive.

A classic rags-to-riches story became a spectacular business failure in the late 1980s when Crazy Eddie collapsed following allegations of extensive financial wrongdoing by Antar and his associates. Shortly after a hostile takeover of the company in November 1987, the firm’s new owners discovered that Crazy Eddie’s inventory was overstated by more than \($65\) million. This inventory shortage had been concealed from the public in registration statements fi led with the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC). Subsequent investigations by regulatory authorities revealed that Eddie Antar and his subordinates had grossly overstated Crazy Eddie’s reported profits throughout its existence.

Eddie Antar was born into a large, closely knit Syrian family in 1947. After dropping out of high school at the age of 16, Antar began peddling television sets in his Brooklyn neighborhood. Within a few years, Antar and one of his cousins scraped together enough cash to open an electronics store near Coney Island. It was at this tiny store that Antar acquired the nickname “Crazy Eddie.” When a customer attempted to leave the store empty-handed, Antar would block the store’s exit, sometimes locking the door until the individual agreed to buy something—anything. To entice a reluctant customer to make a purchase, Antar first determined which product the customer was considering and then lowered the price until the customer finally capitulated.

Antar became well known in his neighborhood not only for his unusual sales tactics but also for his unconventional, if not asocial, behavior. A bodybuilder and fitness fanatic, he typically came to work in his exercise togs, accompanied by a menacing German shepherd. His quick temper caused repeated problems with vendors, competitors, and subordinates. Antar’s most distinctive trait was his inability to trust anyone outside of his large extended family. In later years, when he needed someone to serve in an executive capacity in his company, Antar nearly always tapped a family member, although the individual seldom had the appropriate training or experience for the position. Eventually, Antar’s father, sister, two brothers, uncle, brother-in-law, and several cousins would assume leadership positions with Crazy Eddie, while more than one dozen other relatives would hold minor positions with the firm.

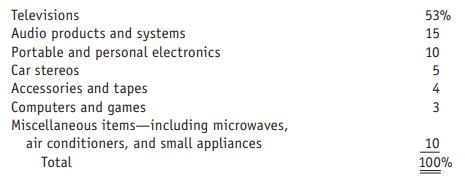

In the early 1980s, sales in the consumer electronics industry exploded, doubling in the four-year period from 1981 to 1984 alone. As the public’s demand for electronic products grew at an ever-increasing pace, Antar converted his Crazy Eddie stores into consumer electronics supermarkets. Antar stocked the shelves of Crazy Eddie’s retail outlets with every electronic gadget he could fi nd and with as many different brands of those products as possible. By 1987, the company featured seven product lines. Following are those product lines and their percentage contributions to Crazy Eddie’s 1987 sales.

Antar encouraged his salespeople to supplement each store’s profits by pressuring customers to buy extended product warranties. Many, if not most, of the repair costs that Crazy Eddie paid under these warranties were recovered by the company from manufacturers that had issued factory warranties on the products. As a result, the company realized a 100 percent profi t margin on much of its warranty revenue.

As his fi rm grew rapidly during the late 1970s and early 1980s, Antar began extracting large price concessions from his suppliers. His ability to purchase electronic products in large quantities and at cut-rate prices enabled him to become a “transhipper,” or secondary supplier, of these goods to smaller consumer electronics retailers in the New York City area. Although manufacturers frowned on this practice and often threatened to stop selling to him, Antar continually increased the scale of his transhipping operation.

The most important ingredient in Antar’s marketing strategy was large-scale advertising. Antar created an advertising “umbrella” over his company’s principal retail market that included the densely populated area within a 150-mile radius of New York City. Antar blanketed this region with raucous, sometimes annoying, but always memorable radio and television commercials.

In 1972, Antar hired a local radio personality and part-time actor known as Doctor Jerry to serve as Crazy Eddie’s advertising spokesperson. Over the 15 years that the bug-eyed Doctor Jerry hawked products for Crazy Eddie, he achieved a higher “recognition quotient” among the public than Ed Koch, the longtime mayor of New York City. Doctor Jerry’s series of ear-piercing television commercials that featured him screaming “Crazy Eddie—His prices are insane!” brought the company national notoriety when they were parodied by Dan Akroyd on Saturday Night Live......

Questions

1. Compute key ratios and other financial measures for Crazy Eddie during the period 1984–1987. Identify and briefly explain the red flags in Crazy Eddie’s financial statements that suggested the firm posed a higher-than-normal level of audit risk.

2. Identify specific audit procedures that might have led to the detection of the following accounting irregularities perpetrated by Crazy Eddie personnel:

(a) the falsifi cation of inventory count sheets,

(b) the bogus debit memos for accounts payable,

(c) the recording of transhipping transactions as retail sales, and (d) the inclusion of consigned merchandise in year-end inventory.

3. The retail consumer electronics industry was undergoing rapid and dramatic changes during the 1980s. Discuss how changes in an audit client’s industry should affect audit planning decisions. Relate this discussion to Crazy Eddie.

4. Explain what is implied by the term lowballing in an audit context. How can this practice potentially affect the quality of independent audit services?

5. Assume that you were a member of the Crazy Eddie audit team in 1986. You were assigned to test the client’s year-end inventory cutoff procedures. You selected 30 invoices entered in the accounting records near year-end: 15 in the few days prior to the client’s fiscal year-end and 15 in the first few days of the new year. Assume that client personnel were unable to locate 10 of these invoices. How should you and your superiors have responded to this situation? Explain.

6. Should companies be allowed to hire individuals who formerly served as their independent auditors? Discuss the pros and cons of this practice.

Step by Step Answer:

Contemporary Auditing Real Issues And Cases

ISBN: 9780538466790

8th Edition

Authors: Michael C. Knapp