The oil and gas industry consists of different activities including upstream exploration and production, midstream transportation (via,

Question:

The oil and gas industry consists of different activities including upstream exploration and production, midstream transportation (via, for example, a pipeline or an oil tanker), storage of crude petroleum products, the downstream refining of petroleum crude oil and the processing of natural gas. Businesses operating in this sector include BP Amoco, Chevron, Elf Aquitaine, Exxon, Shell and Total – brands that we are all familiar with – particularly because, as consumers, we buy automotive fuel from their forecourt retail services.

Companies in the oil and gas market are renowned for being conservative, which is hardly surprising given the harsh and remote conditions in which they work, the potentially catastrophic environmental consequences of errors and the fact that a single unproductive day on a platform can cost a liquid natural gas (LNG) facility as much as $25 million (Winig, 2016). LNG platforms might have five down days a year which represents a significant annual cost, but besides trying to reduce the number of down days, central to operators such as BP Amoco, Elf Aquitaine and Shell is improving the productivity of equipment (assets). Extraction rates of oil wells sit at around 35 per cent, leaving a massive amount of resource unrecovered because existing technology makes it too expensive to extract (Winig, 2016).

Engineering businesses such as Baker Hughes (a General Electric subsidiary), Hyundai and Schlumberger supply process equipment to a variety of industries (including oil and gas), while pump manufacturers such as Sulzer provide components which might typically be part of an OEM’s integrated solution for a new oil and gas installation or replacements for customers’ existing oil extraction or pipeline operations.

For any engineering business, being able to guarantee maximum productive capacity for products is a key part of the commercial narrative when seeking to secure new business and when working with customers to manage the operation of an existing installed base.

Improving productive capacity in the oil and gas industry presents challenges, both for equipment suppliers and customers such as BP Amoco, Elf Aquitaine and Total. First of all, not all equipment in, for example, an extraction, transportation or processing phase is integrated. If a customer transporting gas by pipeline has a problem with a turbo-compressor (used at compressing stations to reduce gas volume), the customer might analyse compressor data when in fact the problem lies with the heat exchanger used to cool this process. Second, while major capital equipment might be installed with sensors and data controls, this is not necessarily the case for less expensive pieces of equipment. This is all well and good, until the day an ‘inconsequential’ pump fails and shuts down an entire production process.

Third, companies operating in the sector invest considerable sums of money in software systems and can handle massive amounts of ‘big data’ for seismic modelling

– used to help with oil exploration and drilling. In fact, the industry more or less invented the term ‘big data’ over 30 years ago. But, when it comes to using data for operational processes and for monitoring equipment central to these, the industry falls over. Even if equipment is fitted with sensors (which would be used for condition monitoring), up to 40 per cent of data is lost because the sensors are binary, that is, they only show if a specific performance parameter is above or below what it should be (Maslin, 2015). This is important but it does not give any indication of trends which could be used to help decision-making and planning (such as preventative maintenance). Fourth, data management for condition monitoring is ad hoc and many companies lack an integrated infrastructure which would enable high-speed communication links and data storage. This means that, in some processes, only 0.7 per cent of the original data generated is used (Maslin, 2015). Companies operating in the sector are beginning to realize that they could learn much from other markets, such as the aerospace industry. Here condition monitoring is used on turbines so that potential failures are seen before they become problems. This has changed the way in which maintenance in the aerospace industry is undertaken, and has reduced maintenance costs by 30 per cent (Maslin, 2015). And because airline operators have more information about the performance of turbines, they are more comfortable with using different turbines, making them engine ‘agnostic’ – this again reducing costs.

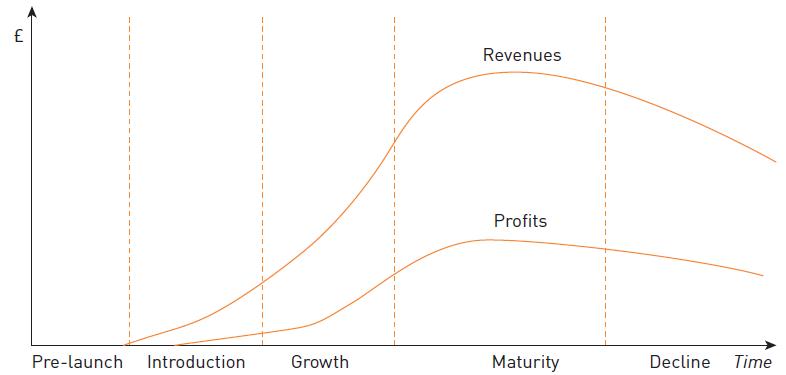

QUESTIONS 1. Using Figure 10.4 , how might you expect interaction and information flows involving ‘sales’ and ‘purchasing’ teams from companies such as Schlumberger and Shell respectively to evolve, as suppliers and customers move from transactions to value co-creation?

Figure 10.4 2. What skills do you consider necessary for members of the sales team in crafting and implementing solutions for customers in the oil and gas industry?

2. What skills do you consider necessary for members of the sales team in crafting and implementing solutions for customers in the oil and gas industry?

3. How might social media be used internally to ensure a shared understanding of and commitment to customer-specific programmes of action?

Step by Step Answer:

Business To Business Marketing

ISBN: 9781526494399,9781529726176

5th Edition

Authors: Ross Brennan , Louise Canning , Raymond McDowell