INA Bearing Company is a medium-sized manufacturer of high-precision engine components for the automotive industry. Based in

Question:

INA Bearing Company is a medium-sized manufacturer of high-precision engine components for the automotive industry. Based in Llanelli, South Wales, it is one of a number of manufacturing companies across Europe owned by the multi-national Schaeffler Group.

In 2001 the company was facing a crisis. Its market position had been declining rapidly since the late 1990s as a result of orders being switched to low-cost producers in eastern Europe. This period resulted in successive reductions in the workforce from around 860 to 360 jobs. In 2001 prospects looked bleak. INA’s German parent had plans to switch even more production capacity to units in eastern Europe which, if implemented, would have resulted in the loss of a contract accounting for around half the plant’s output and further job losses of 120.

Faced with this bleak scenario, the personnel manager led a strategy workshop to reformulate the best way forward. It was accepted that competing with its European counterparts on the basis of cost was not a viable option. Instead INA decided to compete on the basis of quality with a vision to become the group’s preferred location for high-tech production work. At the same time, it was recognised that this transformation in production orientation could not be achieved without radical realignment of the company’s skill base. This led INA to a commitment to compete on the basis of workforce capability. Investment in machinery was to be switched to investment in human capital with the clear intent of building an employee skill base, developing a continuous improvement culture and building towards a learning organisation in order to realise the company’s vision.

In effecting this transformation, INA had to confront a number of potential obstacles. The demands of continuous production severely limited the time available for staff development. The failure of previous turnaround initiatives had left the workforce cynical about management’s intentions. Over time, the demands of production had resulted in the HR roles of managers, supervisors and team leaders becoming diluted. Team leaders spent too much time helping out with production, meaning that the management hierarchy was becoming distorted as supervisors operated as team leaders and managers as supervisors. The grapevine was rife and the works council operated more as a forum for discussing housekeeping issues. Previous attempts to build skills through NVQ (National Vocational Qualifications) programmes had foundered because of lack of time and commitment among supervisors to undertake the necessary assessments of employee competences. The workforce was characterised by long-serving employees who had received little task-based HRD. Lastly, employee relations had deteriorated to the point that some unresolved issues had prompted strike ballots.

In addressing these potential obstacles, INA took two early important steps towards facilitating the desired learning culture where survival was seen to depend on learning faster than the rate of change.

First, one-to-one meetings were held with every employee to explain the company’s vision and signal management’s commitment to that vision. The emphasis was on communicating the company’s position honestly, whereby if the company failed to achieve its vision its decision to base its strategy around HRD investment would have at least resulted in employees having been equipped with high-level, portable skills that would significantly enhance their employability. The second was to forge a partnership agreement with the trade union Amicus. This resulted in the union signing up to the change programme and securing funding for significant investment in the company’s learning centre.

These two interventions have changed the employee relations climate and opened up a genuine two-way dialogue. The individual meetings allowed employees to share their perceptions on obstacles to the development of a learning culture.

They particularly stressed the importance of a unified team. This resulted in the harmonisation of terms and conditions, the introduction of an inflation-linked pay system and the re-alignment of the works council. Shop stewards now report that collaboration has replaced confrontation, evidenced by the way that the works council now plays a key role in developing strategy. Also, the council’s subcommittees have been charged with leading important initiatives. These include a review of internal communications and the development of systems to support company financed individual learning plans (similar to EDAPs).

The platform for skills development was the relaunch of the NVQ programme. This time around, the roles of managers, supervisors and team leaders have been redefined to enable them to commit to their HRD responsibilities. This surfaced a number of management skills gaps among these groups, such as communication, and led to the introduction of an NVQ level 3 in business improvement techniques for supervisors and an NVQ level 3 in management for team leaders. To reinforce their commitment to HRD, senior managers assist in customising training to meet INA’s context and participate in its delivery to those with leadership roles. An NVQ level 2 programme in performing manufacturing operations is being delivered in collaboration with a local college.

This is being taken by all the company’s production operators, some of who are now progressing through levels 3 and 4 of the programme.

Questions

1. How is INA trying to build a learning culture and how would you assess its success to date?

2. In a number of models of SHRD, employees, line managers and senior managers are identified as having important roles to play in its development (for example Mabey et al., 1998; McCracken and Wallace, 2000). To what extent do these stakeholders represent obstacles to the development of SHRD in INA and how are any such obstacles being addressed?

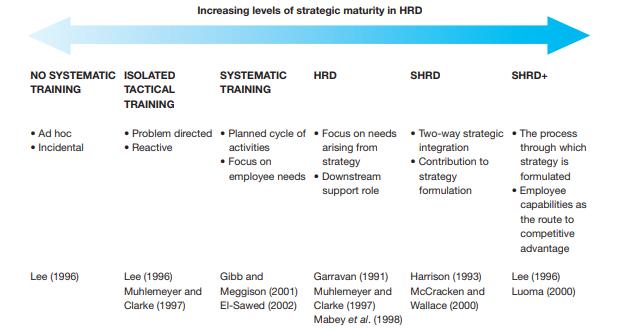

3. Where would you position INA along the HRD strategic maturity continuum (Figure 10.8) and how would you justify your placement decision?

4. Either – what recommendations would you make to help INA move further towards strategically mature HRD? – Or – what further evidence would be needed to justify positioning INA at the SHRD end of the HRD strategic maturity continuum.

Figure 10.8:

Step by Step Answer:

Strategic Human Resource Management Contemporary Issues

ISBN: 9780273681632

1st Edition

Authors: Mark N. K. Saunders; Mike Millmore; Philip Lewis; Adrian Thornhill; Trevor Morrow