Bill French 4 : Bill French picked up the phone and called his boss, Wes Davidson, controller

Question:

Bill French4: Bill French picked up the phone and called his boss, Wes Davidson, controller of Duo-Products Corporation. "Say, Wes, I'm all set for the meeting this afternoon. I've put together a set of break-even statements that should really make people sit up and take notice—and I think they'll be able to understand them, too." After a brief conversation about other matters, the call was concluded, and French turned to his charts for one last check-out before the meeting.

French had been hired six months earlier as a staff accountant. He was directly responsible to Davidson and, up to the time of this case, had been doing routine types of analysis work. French was an alumnus of a graduate business school and was considered by his associates to be quite capable and unusually conscientious. It was this latter characteristic that had apparently caused him to "rub some of the working guys the wrong way," as one of his co-workers put it. French was well aware of his capabilities and took advantage of every opportunity that arose to try to educate those around him. Wes Davidson's invitation for French to attend an informal manager's meeting had come as some surprise to others in the accounting group. However, when French requested permission to make a presentation of some break- even data, Davidson acquiesced. The Duo-Products Corporation had not been making use of this type of analysis in its planning or review procedures. Basically, what French had done was to determine the level at which the company must operate in order to break even. As he phrased it:

The company must be able at least to sell a sufficient volume of goods so that it will cover all the variable costs of producing and selling the goods; further, it will not make a profit unless it covers the fixed, or nonvariable, costs as well. The level of operation at which total costs (that is, variable plus nonvariable) are just covered is the break-even volume. This should be the lower limit in all our planning.

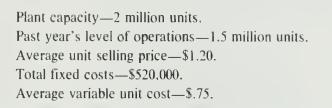

The accounting records had provided the following information that French used in constructing his chart:

From this information, French observed that each unit contributed $.45 to fixed costs after covering the variable costs. Given total fixed costs of $520,000, he calculated that 1.155,556 units must be sold in order to break even. He verified this conclusion by calculating the dollar sales volume that was required to break even. Since the variable costs per unit were 62.5 percent of the selling price, French reasoned that 37.5 percent of every sales dollar was left available to cover fixed costs. Thus, fixed costs of $520,000 require sales of $1,386,667 in order to break even.When he constructed a break-even chart to present the information graphically, his conclusions were further verified. The chart also made it clear that the firm was operating at a fair margin over the break-even requirements and that the pretax profits accruing (at the rate of 37.5 percent of every sales dollar over break-even) increased rapidly as volume increased (see Exhibit A).

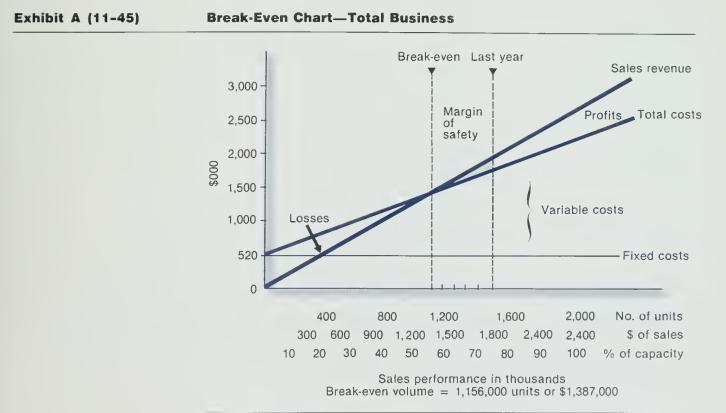

Shortly after lunch, French and Davidson left for the meeting. Several representatives of the manufacturing departments were present, as well as the general sales manager, two assistant sales managers, the purchasing officer, and two people from the product engineering office. Davidson introduced French to the few people he had not already met, and then the meeting got under way. French's presentation was the last item on Davidson's agenda, and in due time, the controller introduced French, explaining his interest in cost control and analysis. French had prepared enough copies of his chart and supporting calculations for everyone at the meeting. He described carefully what he had done and explained how the chart pointed to a profitable year, dependent on meeting the volume of sales activity that had been maintained in the past. It soon became apparent that some of the participants had known in advance what French planned to discuss; they had come prepared to challenge him and soon had taken control of the meeting. The following exchange ensued (see Exhibit B for a checklist of participants with their titles):

Cooper [production control]: You know. Bill, I'm really concerned that you haven't allowed for our planned changes in volume next year. It seems to me that you should have allowed for the sales department's guess that we'll boost sales by 20 percent unitwise. We'll be pushing 90 percent of what we call capacity then. It sure seems that this would make quite a difference in your figuring

French: That might be true, but as you can see, all you have to do is read the cost and profit relationship right off the chart for the new volume. Let's see—at a millioneight units we'd . . .

Williams [manufacturing]: Wait a minute, now!!! If you're going to talk in terms of 90 percent of capacity, and it looks like that's what it will be, you had better note that we'll be shelling out some more for the plant. We've already got okays on investment money that will boost your fixed costs by $10,000 a month, easy. And that may not be all. We may call it 90 percent of plant capacity but there are a lot of places where we're just full up and can't pull things up any tighter.

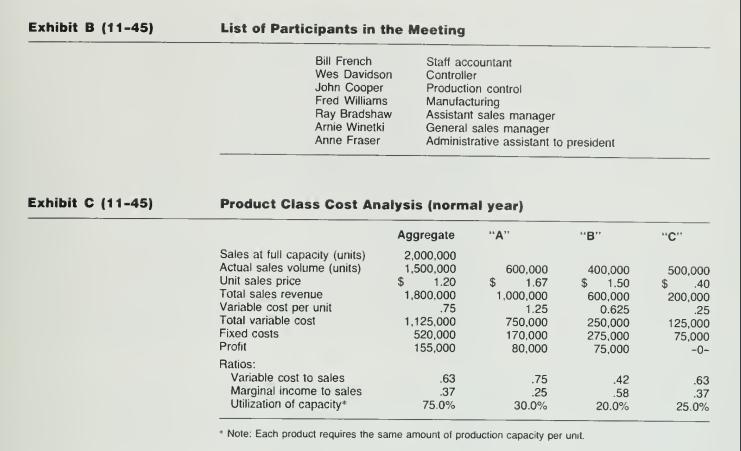

Cooper: See, Bill? Fred is right, but I'm not finished on this bit about volume changes. According to the information that I've got here—and it came from your ff, ce— r m not sure that your break-even chart can really be used even if there were to be no changes next year. Looks to me like you've got average figures that don't allow for the fact that we're dealing with three basic products. Your report here [see Exhibit C] on costs, according to product lines, for last year makes it pretty clear that the "average" is way out of line. How would the break-even point look if we took this on an individual product basis?

French: Well, I'm not sure. Seems to me that there is only one break-even point for the firm. Whether we take it product by product or in total, we've got to hit that point. I'll be glad to check for you if you want, but. . . .

Bradshaw [assistant sales manager]: Guess I may as well get in on this one. Bill. If you're going to do anything with individual products, you ought to know that we're looking for a big swing in our product mix. Might even start before we get into the new season. The "A" line is really losing out and I imagine that we'll be lucky to hold two thirds of the volume there next year. Wouldn't you buy that, Arnie? [Agreement from the general sales manager.] That's not too bad, though, because we expect that we should pick up the 200,000 that we lose, and about a quarter million units more, over in "C" production. We don't see anything that shows much of a change in "B". That's been solid for years and shouldn't change much now.

Winetki [general sales manager]: Bradshaw's called it about as we figure it, but there's something else here too. We've talked about our pricing on "C" enough, and now I'm really going to push our side of it. Ray's estimate of maybe half a million-450,000 1 guess it was-up on "C" for next year is on the basis of doubling the price with no change in cost. We've been priced so low on this item that it's been a crime-we've got to raise, but good. for two reasons. First, for our reputation; the price is out of line classwise and is completely inconsistent with our quality reputation. Second, if we don't raise the price, we'll be swamped and we can't handle it. You heard what Williams said about capacity. The way the whole "C" field is exploding, we'll have to answer to another half- million units in unsatisifed orders if we don't jack the price up. We can't afford to expand that much for this product.

At this point, Anne Fraser (administrative assistant to the president) walked up toward the front of the room from where she had been standing near the rear door. The discussion broke for a minute, and she took advantage of the lull to interject a few comments.

Fraser: This has certainly been enlightening. You clearly have a valuable familiarity with our operations. As long as you're going to try to get all the things together that you ought to pin down for next year. let's see what I can add to help you:

Number One: Let's remember that everything that shows in the profit area here on Bill's chart is divided just about evenly between the government and us. Now, for last year we can read a profit of about $150,000. Well, that's right. But we were left with half of that, and then paid out dividends of $50,000 to the stockholders. Since we've got an anniversary year coming up, we'd like to put out a special dividend of about 50 percent extra. We ought to retain $25,000 in the business, too. This means that we'd like to hit $100,000 profit after taxes. Number Two: From where I sit, it looks as if we're going to have negotiations with the union again, and this time it's liable to cost us. All the indications are and this isn't public—that we may have to meet demands that will boost our production costs—what do you call them here. Bill —variable costs—by 10 percent across the board. This may kill the bonus-dividend plans, but we've got to hold the line on past profits. This means that we can give that much to the union only if we can make it in added revenues. I guess you'd say that raises your break-even point. Bill —and for that one I'd consider the company's profit to be a fixed cost. Number Three: Maybe this is the time to think about switching our product emphasis. Arnie may know better than I which of the products is more profitable. You check me out on this, Arnie—and it might be a good idea for you and Bill to get together on this one, too. These figures that I have [Exhibit C] make it look like the percentage contribution on line "A" is the lowest of the bunch. If we're losing volume there as rapidly as you sales folks say, and if we're as hard pressed for space as Fred has indicated, maybe we'd be better off grabbing some of that big demand for "C" by shifting some of the facilities over there from "A."

Davidson: Thanks, Anne, I sort of figured that we'd wind up here as soon as Bill brought out his charts. This is an approach that we've barely touched upon, but as you can see, you've all got ideas that have got to be made to fit here somewhere. Let me suggest this: Bill, you rework your chart and try to bring into it some of the points that were made here today. I'll see if I can summarize what everyone seems to be looking for. First of all, I have the idea that your presentation is based on a rather important series of assumptions. Most of the questions that were raised were really about those assumptions; it might help us all if you try to set the assumptions down in black and white so that we can see just how they influence the analysis. Then, I think that John would like to see the unit sales increase taken up, and he'd also like to see whether there's any difference if you base the calculations on an analysis of individual product lines. Also, as Ray suggested, since the product mix is bound to change, why not see how things look if the shift materializes as he has forecast? Arnie would like to see the influence of a price increase in the "C" line; Fred looks toward an increase in fixed manufacturing costs of $10,000 a month, and Anne has suggested that we should consider taxes, dividends, expected union demands, and the question of product emphasis. I think that ties it all together. Let's hold off on your next meeting, fellows, until Bill has time to work this all into shape.

With that, the participants broke off into small groups and the meeting disbanded. French and Davidson headed back to their offices, and French, in a tone of concern, asked Davidson, "Why didn't you warn me about the hornet's nest I was walking into?"

"Bill, you didn't ask!"

Required:

a. What are the assumptions implicit in Bill French's determination of his company's break-even point?

b. On the basis of French's revised information, what does next year look like:

( 1 ) What is the break-even point?

(2) What level of operations must be achieved to meet both dividends and expected union requirements?

c. Assume that A's volume will drop to 400.000 units, B's volume remains un- changed, and C's volume increases by 450,000 units. Can the break-even analysis help the company decide whether to alter the existing product emphasis?

d. Calculate each of the three products' break-even points, using the data in Exhibit C. Why is the sum of these three volumes not equal to the 1,155,556 units aggregate break-even volume?

e. Evaluate Bill French's approach in developing and presenting his analysis.

Step by Step Answer: