Question: started realizing there are things that I need to do that are more important than gangbanging and wasting my life in the streets. Even though

started realizing there are things that I need to do that are more important than gangbanging and wasting my life in the streets.

Even though I felt stuck in it. Even though there were 10 dudes that wanted to kill me and there was no way for me to get out of the streets. I started realizing there is more important things that need to be done. I have a daughter. My father wasn’t in my life and maybe if my father was in my life it would be different. If I die, then who is the man that is going to be in her life? I started looking at my family through the generations. Nobody in my family owns a house. They have been living in the poor section of the city. They don’t even have an income. Nobody in my family even had a car. I was the first one to own a car. I want to break that cycle for my family. I want to own a house so that my daughter, when I leave, can take over the house and get things going. I want to get my daughter away from living in those parts of the city. I don’t want her around that.

~ Joe Sierra, ICW trainer and former InnerCity Weightlifting student3 Section 1: Is the Time Right to Expand to a Second City?

Jon Feinman, founder and executive director of InnerCity Weightlifting (ICW), was working out in one of ICW’s Bostonarea gyms as he did every day. ICW is a nonprofit focused on reducing recidivism by giving young men who are active in the streets the tools to turn their lives around. Jon was proud that ICW was having a profound impact on the lives of its students like Joe. Jon wanted to grow ICW so it could impact more young people involved in gangs and the streets. He was contemplating a potential major growth initiative: should ICW expand beyond Boston? He had planned to expand to other cities since founding ICW, and he and the board had chosen Philadelphia as a possible next location.

There are approximately 1,150,000 gang members in the United States distributed among 24,250 gangs, some local and some national.4 ICW’s unique program helps transform the most hardened gang members in Boston into a better life outside of gangs. Jon wondered whether ICW’s high‐touch model could scale. Could other cities replicate the Boston model? He wondered if ICW worked because the team really understood Boston. He worried that other cities and gangs might be very different and that the model might not fit elsewhere.

As CEO of a nonprofit, Jon knew there was a lot riding on the decision. While growing ICW into a national model was his dream, expansion posed several risks, especially for the financial well‐being of his company. There were lives on the line if ICW did not work in Philadelphia; worse, a misstep could potentially set the Boston operation back by damaging ICW’s financial well‐being and reputation. The Philadelphia move might be successful, but it could put a crushing burden on the lean management team if other cities increased pressure on ICW to expand there.

ICW works to reduce street violence and recidivism of the highest‐risk youth in the city. One percent of Boston’s youth is responsible for over 50% of the city’s gun violence. This one percent is about 400 people who live mostly in the neighborhoods of Roxbury, Dorchester, and Mission Hill. This list of 400 people, called the PACT list, includes those most likely to kill or be killed, identified by the Boston Police in its Partnership Advancing Communities Together program for reducing street violence in Boston. Most of these individuals are affiliated with a gang and have done significant jail time. The Boston Police call them “high‐impact players.” ICW identifies and recruits this group of young people to be their students.

ICW helps its students turn their lives around by building trust, instilling hope, and providing opportunity. Not many organizations are willing to work with this population, but Jon believes transforming even a few gang members will have huge benefits not only for the students, but also for the greater Boston community. He believes the model will bring systemic change by reducing violence and changing society’s perceptions of the demographic that makes up his student population.

Jon always had the goal of expanding from Boston to other high‐profile cities to achieve national systemic change. He feels that after almost eight years of operation, now is the time. He knows there is great demand for ICW to expand to other cities.

When ESPN ran a short documentary in 2013, the ICW server crashed twice as people from all over the country and around the world posted messages and sent e‐mails requesting information about how to start a chapter in their city. But big unanswered questions remain: is ICW ready for expansion? Will Jon’s model be sustainable in another city? Will Philadelphia, the city chosen for expansion, have the same positive reaction as Boston? Can ICW work without Jon there at every step?

Jon knows the risk is great. While expansion could certainly transform more lives in more places, if it is not executed properly, it could also cause ICW to lose its intimate mode of operation, arguably the biggest factor for current success.

Furthermore, failure in Philadelphia risks hurting ICW beyond repair, thus closing the doors not only to Philadelphia’s highimpact players but also to ICW students in Boston as well.

Without ICW, many might not have any option but to turn back to the streets for survival. And on the streets, the six‐month outlook for these young men is jail or death.

The Beginnings of a Social Entrepreneur Jon grew up in Amherst, Massachusetts, a small, wealthy, suburban town that provided him with plenty of opportunities.

“I grew up in a family and community with connections and opportunity. I went to college because everyone I knew went to college. That was really my only focus growing up. After working with ICW students, I recognize how much I took for granted.”8 College was Jon’s primary focus. He figured he would graduate, start a career and a family of his own, and live the American dream like his parents and all the people he grew up with. With the luxury of being able to choose from various extracurricular activities, Jon took up many hobbies, including soccer. He excelled at soccer, and after graduating from high school, he was recruited to play for Bryant University. At 5′8″ and 160 pounds, Jon had always been an undersized athlete. To compete at the collegiate level, he started taking weightlifting very seriously. His dedication to weightlifting throughout his undergraduate years led him to certification and his first job as a personal trainer.

Jon started studying to be a personal trainer after college. He enjoyed the science behind the sport and later, the relationships he built with his clients. During the first year after graduation, Jon’s main commitment was his work with the AmeriCorps program, Athletes in Service in America.9 He was stationed at a kindergarten through eighth grade school in East Boston, and his role was to involve kids in after‐school sports programs.

Jon was drawn to a group of young people associated with one of the nation’s most violent gangs, MS‐13. Other counselors told him not to bother with this group—they were too dangerous and definitely didn’t care enough to change—but Jon was determined to make contact and build a connection. At first they paid him little notice; they were suspicious of Jon as he self‐described himself as the “small white kid from Amherst Mass.” The kids, mostly of color from the inner city of Boston, didn’t relate to Jon. One day while the boys were playing soccer, Jon saw his opportunity. After showing them some tricks, Jon earned their attention. He started to break through the trust barrier by playing soccer and lifting weights with them. During this time, he got to know them for who they were as people beyond their MS‐13 label and learned from them something that forever changed his perspective.

I recognized what I believed to be confusion between lack of care and lack of hope. People call them thugs, gang members, criminals, and whatever other word they want to throw out to basically write them off, because they think they don’t care and that you can’t really do much for someone who doesn’t care. What I saw was very different. No one wants to end up dead or in jail, and yet they are willing to lose their life to a bullet or jail to be there for each other, to care for each other. I saw this really genuine form of care, and I saw what was lacking was not care, but hope. That realization was empowering because hope is something that I felt I could do something about, and more importantly, we as a society could do something about.10 Spending time with the young people eventually helped Jon discover what drove them to the streets. They lacked hope and opportunity and a network to access opportunity. These young people only have the support of their fellow gang members, which leads to gang activity and street violence. If the lack of hope and opportunity led to violence, what is it that drains hope and opportunity?

I started to recognize the system. [Our students are] born into families and communities that are segregated and isolated. Unlike myself, they have to worry about rent, they have to worry about food, they have to worry about clothes. There’s no way that school can be their only focus.

So they turn to the streets to solve the real challenges that they face today, because they don’t get to see tomorrow unless they take care of those short‐term obstacles that are in their way. Rather than leveraging an education to find a meaningful career, they find themselves in jail. They come out more segregated and more isolated. All along the way everyone calls them a bad decision‐maker, when in reality, they don’t have a single good option to choose from. This whole system gets perpetuated every time someone like myself during that year [in AmeriCorps] was told stay away from them: “Don’t cross this street; it’s dangerous over there.” That very avoidance creates segregated and isolated pockets of communities which leads to a lack of resources, lack of opportunity, inequality, poverty, and the need for the streets in the first place, which manifests itself in violence.11 Jon had always been considered a good decision‐maker by society, but he realized this was because he only ever had good options to choose from. On the other hand, society looks down on his students’ decisions and punishes them through the criminal justice system. While these decisions might lead to actions that break the law, the decisions themselves are not illogical. Their decision‐making process isn’t what is flawed, it is their options, limited by a society that has written them off.

Getting to know these young men helped Jon start to recognize the system of segregation and isolation that left this population with only bad options. Thus, leading to street violence with death or jail as the most likely outcomes.

Many of Jon’s realizations took place during his time in AmeriCorps, but it took him a while to develop those ideas and start thinking of a solution. When Jon’s year in AmeriCorps ended, his work as a personal trainer expanded from a side gig to his full‐time job. After another year or two of working for himself as a trainer, at age 24, he had a full schedule of clients and a comfortable salary. Jon was uneasy with the fact that he had reached this top level of success in the field at such a young age. He knew he could continue like this and lead a comfortable life, but he wasn’t satisfied. Jon decided to pursue the idea that he had been contemplating since AmeriCorps.

The Founding Story of ICW There isn’t one moment that Jon can point to as the moment when the idea for ICW came to him. Rather, the idea started forming as a combination of his life experiences and his feeling of being stuck in a career at age 24. While Jon was talking to one of his personal training clients about his concerns, he realized he could use his trainer skillset to make a social impact.

Although he had lost contact with them, Jon had not forgotten about the young people he met during AmeriCorps. He had enjoyed working with them and was still passionate about making an impact on their lives. Using sports and lifting had worked to connect with them then, so why couldn’t it work again?

Once the idea that would become ICW started forming in his head, Jon decided to take a big risk. He put himself in debt to go to Babson College to get his MBA. To this day, Jon says it was one of the best decisions of his life. Going to school for an MBA is what allowed his idea to grow. Jon started piloting his business plan while at Babson. He was able to use an acquaintance’s gym space for two hours, three days a week, to start working with their target students. While in his pilot period, Jon received a piece of criticism that led to the basic approach for running ICW today. Jon was told that he had no idea what he was doing, and he agreed. “Since I had no clue what I was doing, I really only had one option. To LISTEN. I think too often, especially in the nonprofit sector, we try to solve problems from our own privileged perspective, that somehow if we can get kids onto the path we followed, their lives will be better—it worked for me, so it should work for everyone else.

This is flawed logic.” Jon started listening to his students and realized his original business plan wasn’t going to work for ICW’s target population.

Originally, Jon thought he would reduce violence in the target population by using weightlifting to get kids into the Olympics or win college athletic scholarships. After listening to the students he was working with, Jon soon realized his original idea was deeply flawed. “Knowing this was the population we were working with and reducing violence was our end goal, there’s probably a million different ways to get there. To succeed, we needed to let the students define their own path and shape the organization off that. Like I said, I don’t know what they have to go through on a day‐to‐day basis.” It turns out, just getting these young men in the gym, off the streets, lifting together and building a community not based on violence, was much more realistic, effective, and far‐reaching in impact than trying to get them college scholarships or Olympic glory. This change in philosophy led Jon to make adjustments, including letting go of some of his original coaches because they were too focused on the lifting and not on the connection and community aspect that ICW needed to center around. Jon now viewed the gym and weightlifting as a “hook” to attract his target population. He built a community and support system to accomplish the larger mission of helping his students redirect their lives. After this change in model, ICW really started to grow into what it is today.

How ICW Works InnerCity Weightlifting’s entire philosophy is centered around a promise. “What this organization is about, is that we don’t promise to solve [our students’] short‐term problems, because they are too severe and honestly, we can’t hope to fix them. What we do promise and commit to is being by their side so they don’t have to solve these problems alone. That became pretty powerful.” As Joe Sierra, a student turned trainer through ICW’s program notes:

When I talk to these kids, some of them have been shot already. I ask them what they want to be when they grow up, and they don’t even have an answer. They shrug their shoulders. Some of them say they want to move bricks, you know kilos of cocaine or heroin. They think they’re going to be Pablo Escobar. “You are not going to be Pablo Escobar.”

I try to help them. I tell them what I’ve been through, what I’ve seen. Working individually with each person allows ICW to help students discover another way to live their lives. The incarceration recidivism rate for ICW’s target population before starting the program is 80%. Among those students who continue through the program long enough to develop hope and real alternatives, the rate drops to 8.2%. One of the reasons ICW is effective in reducing these rates is that they do not give up on their students. They do not require students to make it through all its stages consecutively or to “graduate” from the program.

Many students are arrested, shot, or stabbed at different points while in the program; but Jon and his staff stand by their promise to help their students no matter what—visiting them in prison or in the hospital, going to court appearances, and writing to them while they are behind bars. ICW also provides formal weightlifting training so that students may achieve certification for a career as a weight trainer. The program also helps students who did not finish high school to earn a GED. This promise applies to students in all stages of the program. Once ICW reaches out to someone, the staff is there for that student no matter what.

Cali, an ICW student who has started his own personal training program and attends Bunker Hill Community College, agrees with this philosophy. “At the end of the day, all anyone around here can do is do what they can do for these kids. Do what you can do and don’t ever give up on these kids.” ICW has developed four main sequential stages that students work through: Trust, Hope, Social Capital, and finally Economic Mobility. Originally, ICW sought students through court referrals, street workers, and juvenile detention centers.

Now, ICW has grown enough in Boston that it only needs to rely on word‐of‐mouth, their current students bringing friends to the program. ICW works hard to ensure they are only admitting students who are truly in their target demographic, which is that 1% who are most susceptible to street violence. Most of ICW students have shot, been shot, done significant time in jail, and come from a family that makes less than \($10,000\) a year.

If someone is referred to ICW who is not in this demographic, ICW refers them to another program.

ICW determines if a potential student is part of their target demographic during an extensive screening process. To maintain the safety and security of everyone inside the gym, it is imperative that ICW not mix rival gangs. During the screening process, ICW must establish the student’s identity within gang dynamics to ensure that it is safe to bring them into the gym.

We recognize the fact that we just don’t know. We’ve developed a process that takes everything off‐site, and we don’t give away our locations publicly. We incorporate our students in that process. If we don’t know the person, our next step is to ask the people we are working with:

do you know this person? Do you know this group? Our own people actually have a big say in whether or not that person ends up at the gym, and it allows us to make sure we are keeping everything safe even before we know the new candidate. Angel LaCourt, who has been with the program for six years and is now a certified trainer and student intake coordinator, laughed when asked about his own screening process.

My friend brought me to the gym, and I met Jon for the first time. But, there was a whole process before I met Jon that took place without me even knowing. My boy [friend] asked Jon if I could come before he even asked me to come. Someone did intake with me, and there was a whole process and it was just crazy the way it worked.

I was like “S*** when was I going to be notified that this was going on?” Jon didn’t tell me until a couple months later when I asked “How come I didn’t go through that [intake process]?” and he was like “You did, you just didn’t know it happened,” and I was like “That’s cool”… I understood why too, because it was for everyone’s safety.19 In his current role as student intake coordinator, Angel helps with the screening process by reaching out to potential students, talking to them, and learning about their background and goals.

The initial stage, Trust, takes place mostly outside of the gym as part of the screening process. Within the first stage, ICW measures a student’s success through his willingness to communicate.

The first big step is to get their phone number, which already requires preliminary trust from the student. Then ICW looks at the communication ratio they have with each student.

Does the student call or text back when ICW reaches out? At a minimum, ICW likes to have at least eight points of contact within a month with each student. This can be by phone or text, appearance at the gym, or a car ride to and from the gym. During this stage, ICW staff is building trust with students by listening to them and breaking down small barriers that are preventing them from coming into the gym.

Once you start listening, you hear that someone is actually interested, but they can’t get here safely. So I say, “Well, I’ll pick you up tomorrow if you want.” As you listen, you start hearing how someone wants to come to the gym and work out, but they don’t have a pair of shorts. Well, we can buy you a pair of shorts. Someone might come here and, more often than not, they haven’t eaten that day – let’s go out for lunch. A lot of our guys, they get out of jail, and they don’t have an ID and yet they’ll still have probation fees and they need a job, but they can’t get a job without an ID and they don’t have any money. We take them and buy the ID for them. By listening, you start to solve problems and earn someone’s trust in these seemingly simple ways, which are actually pretty profound. If you can’t pay your probation fees and you can’t get a job, you are left with one choice:

go back to the streets and solve your problems the way know how. Stage two, Hope, is all about engagement in the gym. Success in the second stage is eight engagements beyond just small conversation. Once students start coming to the gym regularly and are comfortable at ICW, they start to have hope that longterm goals are possible. Then they move on to the third stage.

As Cali notes, “You have to go through a process that allows you to grow through the levels. The majority of that process is pretty much dedication and just showing up and really being disciplined about learning about fitness, doing some of the exercises yourself, learning about program design, and stuff like that. I took it seriously coming through the door. Stage three, Social Capital, is where ICW’s in‐house personal trainer training comes into play. The end goal for this stage is making meaningful connections and building genuine relationships with clients to bridge social capital across socioeconomic classes. This is when student networks really start to grow; they are training clients who come from six or seven figure backgrounds, Boston area professionals who work in finance or large corporations. Building these relationships eventually connects students to opportunities either directly from or within the clients’

extensive networks. Furthermore, all ICW students have access to everyone and everything in ICW. This provides all students with a network, no matter their stage or whether they have built a personal training clientele. For example, Jon found out that Mack, one of ICW’s students, was interested in consulting.

Jon knew someone else’s client who worked for a consulting firm, and they set up an opportunity for Mack to shadow someone at this company. Opportunities like these eventually lead students to potential jobs. While these connections with clientele from the opposite socioeconomic background impact students greatly, clients are affected as well. ICW sends out surveys to its clients, and many say their perspective on this population has changed. Clients consider many of the trainers to be friends and vice versa. When asked about his relationships with his clients, Cali lit up. “Oh my clients?! Me and my clients are homies! Yeah, we’re good, we’re friends!”22 Many clients meet with their student trainers outside of the gym, inviting them to dinner or some other activity. The gap between these two populations begins to be bridged and an altered, positive perception starts to spread. “To be successful, we always need high‐net‐worth clients to come. We run corporate training programs to try to bridge the gap between people of wealth and people of poverty. If they don’t come together, you can’t grow—we need them to grow, they need us to grow—we can’t do it separately.” The last stage, Economic Mobility, is what ICW defines as earning over \($30,000\) a year. In this stage, success is measured by how much money students are making. ICW knows how much students still in the program are earning and can estimate what students with jobs outside the organization are making. In addition to income and long‐term employment, ICW also looks at recidivism rates and life stability as measures of success.

During this stage, ICW hopes students will start to make enough money to think more about their future, instead of having to spend all their time, energy, and money on the problems of today. Joe Sierra, who has been with ICW for nearly six years, is now on salary at ICW as a trainer and is saving to buy a house.

That’s my focus on life right now, is me trying to get to where I want to get to, I mean I have three jobs, I’m on salary here at InnerCity Weightlifting because I have been with them for so long. I train anywhere from 40 to 60 clients on top of what I make. I work at another gym.

And then I also work at a Dorchester brewery where I also get paid well. I’m going good. I meet people in college that don’t even make the money that I make. I travel a lot. Every month or two. I have 20 stamps in my passport. ICW also looks at the critical points when students reach a bump in the road. Do they have a new network that can support them through it, or do they have to return to their old gang networks?

The recidivism rate of students who reach stage four is less than 8.2%. For students who leave ICW before completing all the stages for another job opportunity, data shows they are more likely to go back to jail.

All students do not study to become personal trainers, as this is not the career for everyone; but regardless, all ICW students are working to become ICW certified. The ICW certification requires basic skills to run a client through a training session.

Working toward this certification adds structure to a student’s program as they work through stages two and three. It also allows for a sense of accomplishment when completed and inspires students to pursue a career in personal training and study for an official personal training certification. Some, like Cali, know right away that personal training is for them. “After four to six months, I was running my own show. Even though I represent ICW, I pretty much go out there and get my own clients.

I have been doing that for probably about a year now.” Other students take to it more slowly. Angel admitted that at the beginning, personal training was terrible for him because it was hard to get clients. It took two years for him to reach a point where his schedule was full. While Angel enjoys personal training, he wants to do something else for ICW in the future.

“I definitely see myself with ICW, but doing something just a little bit different one day. [Eventually,] I want to open up an InnerCity Weightlifting Gym myself, just to give back and show

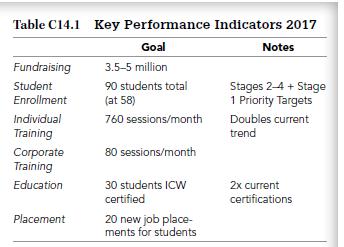

dudes that there is hope. Because Jon gave a lot of us hope when we thought there wasn’t any.” While ICW uses stages to track success of its students, they have a set of key performance indicators (KPIs) that allow them to track success of the organization as a whole. Table C14.1 identifies ICW’s KPIs.

Todd Millay, the president of ICW’s board, notes:

One challenge is how do we measure success? How do we know if this is working or not? How does a donor know that this has been a good investment relative to the other things they could’ve done? I think that is a really hard question. We’ve developed a variety of metrics that we use to measure success. I think we’ve done a better job measuring success on the student side, the original narrow purpose of ICW. It is very challenging to measure the broader sense of that. What impact have we had on all the clients that have come into our gym? When they see a scary‐looking African American guy walking down the street, do they cross the street? Do they make an assumption about somebody? All these little things that help to ingrain the isolation and segregation of this population, are we ameliorating those or not? If we are, that is tremendously important. The ICW team is still figuring out how to best measure changes in client attitudes, but hopes that it will eventually show the national impact and systemic change that ICW promotes.

ICW’s first gym location is in Dorchester. When the client training aspect of the program began to grow, ICW and the board began to believe that expansion to a second location would help students interact with high‐net‐worth clients. Todd Millay understood the need for growth from the unique perspective of both client and now ICW’s board chair.

I think Dorchester is awesome. I love the gym, I love going there, but it can be intimidating. I’ve had several people that I was surprised were just unwilling to go to that gym. People that I didn’t think of as particularly timid, people who I thought would really like the experience, but just the idea of going down to Dorchester, going through a metal detector, it was intimidating.

Half of ICW’s mission is focused on not only the students, but the broader community that they’re isolated from, and making connections with them. That was what was missing with Dorchester. Only a small subset of that [wealthier] community would be willing to go down to Dorchester. That limits the economic opportunity of the students.29 In the spring of 2015, ICW opened its second Boston‐area location. The Kendall Square facility was designed to operate mostly as a client‐training gym. ICW chose this location because it allowed ICW to focus on its goal of bridging the gap between the student population and the clientele. Kendall Square is in an area with no gang presence, which helps maintain the safety of the students and the clients they train. On the business side, Kendall Square is a favorable location, because there are not many competing gyms in the area to serve the growing presence of tech companies. While clients can still train at the Dorchester gym, its main function is offering a place for students to work out and work through the stages.

Jon’s unique model and ICW’s success since its launch have earned recognition for both Jon and the organization in greater Boston. Jon has won the Heroes Among Us award from the Boston Celtics, the Babson College Rising Star award, the Outstanding Community Partner Award from YearUp, the Lewis Institute Changemaker Award, along with awards from Good Sports, Cabot Creamery, Anytime Fitness, and two from Bostinno.

Jon was also Social Ventures Partner Grantee in 2012, one of the Ten Outstanding Young Leaders named by the Greater Boston Chamber of Commerce in 2014, and the Ernst & Young New England Social Entrepreneur of the Year in 2015. And ICW as an organization won the Rosoff Award in the Nonprofit Diversity Initiative Category in 2015.30 The local recognition has helped Jon grow ICW and garner more support.

Resources ICW is a 501(c)3 nonprofit corporation. Its funding comes from three different sources. Around 70% of ICW revenue comes from corporate donors and philanthropic foundations such as the Lynch Foundation, Devonshire Foundation, Baupost Group, State Street Foundation, John Hancock Foundation, and Highland Street Foundation. Many of these foundations fund ICW with yearly or multi‐year grants. ICW also applies for city and state grants. The second revenue category is individual donors, which brings in 15% of ICW revenue. Most of these donors are relationship‐based repeat donors. Many clients who train at the gym also make contributions. ICW has a program called Elexson’s Club, which has donors who give over \($1,000\) each year. The third source, accounting for 15% of ICW revenue, is earned income from individual and corporate training sessions which ICW runs and students provide. Individuals can purchase a one‐time session, a pack of sessions, or a monthly unlimited number of training sessions. Each session costs a client \($25\). While this is a source of revenue, most of the \($25\) goes directly into the pockets of ICW student trainers.

Almost all payments now are done through credit card. At the lowest rate, clients will pay \($25\) a session and students keep \($20\) of that. We put our trainers on W‐2s, unlike traditional gyms that will 1099 their trainers. That way, our students don’t have to worry about the employer‐side taxes. Their taxes come out of their checks and we just take care of all of that for them. They don’t have to worry about [taxes] at the end of the year. Between the employer‐side taxes, mind‐body software, and credit card fee, we net \($1.70\) from the transactions.31 While ICW hopes to grow its earned income revenues, it does not want to do so in a way that would reduce student income. Jon stresses the importance of fundraising strategies that align with ICW’s mission. “Because our clients are paying a reduced rate and because they get to change lives while changing their own, they become our donors. It creates a sustainable donor cultivation strategy. We can actually make more money off of client donations than we could trying to take an extra 20% that would come out of our students’ pockets and just wouldn’t feel right in any way.” And clients feel good about choosing ICW. As Todd Millay highlights:

For me, I think ICW is addressing one of the fundamental problems in America. The segregation and isolation of a part of our population and the increasing disparities of wealth. I think Jon’s sense that this can be a vehicle to break down that isolation on both sides is quite insightful, and personally I have benefitted from it tremendously.

Because I would never know Reggie or any of these guys if it weren’t for ICW. So I feel like I have forged some very meaningful relationships in my life from having that first‐hand experience and just having a conversation about what their lives have been like. I think it’s important for any of us on the other side of the divide to be doing something about it. This was a way that I saw that would be sustainable for me to make a meaningful contribution.

Any nonprofit activity when you already have a demanding job and an active family life has to be something you’re really passionate about. Despite all ICW’s fundraising efforts, the budget is still tight. More resources are needed to improve ICW’s operation in Boston. First and foremost, ICW needs more staff. They need more drivers to bring students to and from the gym, a larger administrative staff, and a donor outreach team. Furthermore, to better serve the target population in Boston, ICW needs an additional location. Right now, they cannot bring people from rival gangs to their gyms. This prevents ICW from reaching the PACT population at the depth their program aspires to. In the future, ICW hopes to open another site in either Roxbury or Mission Hill to serve rival gang members.

The Philly Opportunity Jon’s motivation for growing his company is unique. The more ICW grows, the more high‐risk young people it can reach across the nation, and the more it can lower street violence nationwide.

Jon has a larger goal than lowering street violence or even changing the lives of ICW’s target population. Jon wants to grow ICW to shift the national perception of this target population and change the narrative surrounding issues of violence, incarceration, isolation, and segregation that these people face. Jon’s theory is that if ICW can create this effect in key, high‐profile cities, then that will be enough to start real national systemic change so that ICW doesn’t have to be in every city.

ICW believes it can help start a national conversation about how segregation and isolation in impoverished communities create a need for gangs, and how segregation and isolation continually fuel and are fueled by mass incarceration. Further, ICW believes this dialog will create more opportunity and inclusion on a grander scale.

ICW has identified four additional high‐profile cities with significant street violence: Philadelphia, Baltimore, Chicago, and LA. Philadelphia is the logical location for the first expansion because it is geographically close to the home base in Boston. After sharing the idea of starting ICW in Philadelphia, the target population of gang members, government officials, and additional stakeholders have expressed strong positive reactions. As Josh Feinman, Jon’s brother and ICW Director of Development and Communications points out,

“We heard from a lot of people that they wanted us to be there tomorrow. When we were telling them that it might be a year out or so, they were like, well we could use this program tomorrow.” The ICW team has chosen now as the time to expand to a new city because it recognizes the opportunity to build a national brand and spread their message. “Right now, as a society, we’re still trying to solve this problem by further segregating and isolating people, first by circumstance, but then by prison and incarceration. By expanding ICW, we are hoping to build more awareness about what can be done by bringing these disparate groups together, instead of pushing them out.” After eight years of experience in Boston and successful expansion to a second Boston location, the ICW team feels ready to take on this next step toward developing a national voice. Jon knows the risk is great. Failure in Philadelphia risks hurting ICW beyond repair, but not trying equates to a bigger failure in Jon’s eyes. “I’ll feel like we failed if we’ve been around for decades and we’re still just in Boston and haven’t made that national impact, because we won’t have made the systemic change nationwide that we set out for. I think there is a bigger risk on the side of not growing. That being said, we are very aware of the risk involved with growing, especially as it relates to financial sustainability.”36 The most important thing to the ICW team is to make sure the integrity of the mission and operation is maintained with expansion. A good leader is essential to achieving this goal.

Josh Feinman, the current Director of Marketing and Communications and Jon’s brother, volunteered to lead the expansion in Philadelphia. At the time Jon was piecing the idea of ICW together in his head, Josh was working with him as a personal trainer at the same studio. When Jon launched ICW in 2010, Josh was one of the first volunteers. He does a lot of work building and maintaining relationships with both corporate and individual donors. He has learned many lessons about leadership from watching Jon build ICW for the past eight years. For example, Josh is more emotional and likely to speak up if something happens that bothers him. He has learned to moderate his emotions based on Jon’s example. He understands that becoming visibly upset with an unfriendly potential stakeholder can negatively impact ICW and its students in the future.

The ICW team and board are all confident that Josh is a good fit to lead the expansion. He has been with the organization from the beginning and is very passionate about its mission. “When it comes to expanding, we need to have the right leaders in place who understand our model from the ground up. I think for us to feel comfortable, we have to have leaders within the organization involved in the expansion.”37 Road Map to Philly The current rough plan for Philadelphia expansion is for Josh and ICW head coach, Regan Feinman, to move there for two years. During this time, Josh will be hiring and training staff and identifying local leaders who can continue the operation after he leaves. It is important that Josh build a staff dedicated to the intimate nature of ICW’s program. He needs to find people who, no matter their title, will be willing to give rides, go to court dates, and always listen to their students and attend to their needs. Josh has already organically been building a volunteer staff as interest in the city spreads. The goal is for the Philadelphia operation to be self‐sustaining at the end of his two years. If all goes well, Josh will then return to Boston with a playbook for further expansion.

ICW has held focus groups with the young people they have been able to contact. At these focus groups, current ICW students have been able to chat with Philadelphia’s high‐risk youth. From listening to people in their target population, the ICW team has learned that there are different dynamics in Philadelphia from those in Boston.

It’s a very different city, and we’re learning that as we go, again by the philosophy of listening as much as possible.

I think it’s different on almost every level, even though there are some similarities. In Boston, you seem to have these groups of young people who have very clear beefs with other groups and territories. In Philadelphia, so far, it seems like the lines are a little more blurred. This is something we need to learn more and more about to be effective there.38 Although Philadelphia is two times bigger than Boston, Jon and Josh have learned that it still has a small city feel; you are likely to run into more people you know, and the city’s population is more connected than in other large urban centers.

Everything that ICW is learning from the focus groups will be further investigated on a larger and deeper scale as planning and development continue. It is essential for ICW in Philadelphia to know enough about the city’s dynamic to ensure the safety and security of its students and staff.

In terms of funding stakeholders, ICW started making connections in Philadelphia after Jon spoke at the Aspen Institute in DC. Here he met a man who ran a foundation in Philadelphia and took interest in ICW. The ICW team took a trip to Philadelphia to meet with him, and networking spread from there. ICW currently has \($70K\) in seed capital but will not launch in Philadelphia until they have raised \($500K\). On top of securing more funds, ICW is in the process of putting together a local advisory board to help with expansion.

ICW has the goal of making the Philadelphia model self‐sustainable within two years; and to achieve this, they must build both individual and corporate clientele much faster than they did in Boston. Building clientele in Philadelphia is crucial to sustainability because there are not as many resources for nonprofit funding as in Boston. ICW is hoping to rely more on earned income from personal and corporate training for revenue. In Boston, earned income is about 15% of revenue. In the future, ICW hopes to grow this to 30% in Boston and hopefully more in Philadelphia. Jon explained his concern. “I think the big concern, from my perspective, is whether it is going to be sustainable.

How do we know from year one if this is working really well, or if it is time to say, hey we learned a lot but we need to scale back and get back to Boston because this thing is going to put us under. I think any time you grow, you’ve got this risk of hurting the organization unintentionally.”39 While financial sustainability, safety, and security are major risks of expansion, another is that the ICW team might dilute the effectiveness of their work back in Boston. This could happen if the team is spread too thin or distracted by the Philadelphia operation.

Josh thinks the most important way to mitigate dilution is to maintain open lines of communication between the Boston and Philadelphia operations. The ICW team has adjusted operations at the two Boston sites, based on what they have learned from each location. This mutual learning must take place in regular communications.

According to Josh, it is essential for the Philadelphia operation to inform the Boston operation and vice versa.

While confident, Jon has a fear of dilution but also a concern that a Philadelphia failure will let down its students.

The biggest fear I had with starting ICW was that even though I thought it was going to work, somehow I wasn’t going to be able to sustain it as a leader because I didn’t know what I was doing. I think it is similar with Philadelphia. If we don’t know what we are doing, are we going to become just another door that opens for the people we work with, to ultimately shut it in their faces because we couldn’t figure it out on our end. That was my biggest fear here.40 ICW is changing the lives of this population and starting to have an impact on members from the opposite side of society.

This program has shown amazing results, causing recidivism rates to drop from 80% to 8.3%. Failure would end access to creating opportunity for a better future, but not trying would leave high‐impact players around the globe without the chance to partake in a program that is actually working.

Decision Point The exact date for expansion is still up in the air. First, ICW must reach its set milestone of \($500K\) in funding before starting in Philadelphia. If this goal is achieved in the next year, the earliest that ICW would move to Philadelphia is next summer (2018).

Other factors could delay the move. ICW is also currently looking at possibly expanding to a third location in Boston.

The South Boston Waterfront Neighborhood Association Seaport (SBWNA Seaport) has offered ICW a site. This site is in an affluent area and would function like the Kendall Square site to train clients. The problem with this project is that ICW cannot afford the rent for the building. ICW is currently discussing options with the landlord. If this project progresses, Philadelphia might be put off for a little longer.

As Jon looked at the Philadelphia expansion opportunity, he was torn. Expansion was central to his vision, but it could risk the success that ICW had achieved in Boston. As he continued lifting, Jon wondered if expansion was a good idea.

Discussion Questions

1. Should ICW expand to Philadelphia?

2. Besides financial, what obstacles would such an expansion face?

3. Can ICW replicate its Boston success in Philadelphia? What are the key factors that need replication?

4. While Josh has worked for ICW since the beginning, is he the right person to lead expansion?

Table C14.1 Key Performance Indicators 2017 Goal Notes Fundraising 3.5-5 million Student 90 students total Enrollment (at 58) Stages 2-4 + Stage 1 Priority Targets Individual 760 sessions/month Doubles current Training trend Corporate 80 sessions/month Training Education 30 students ICW certified 2x current certifications Placement 20 new job place- ments for students

Step by Step Solution

3.33 Rating (159 Votes )

There are 3 Steps involved in it

Discussion Questions 1 Should ICW expand to Philadelphia Pros of Expansion to Philadelphia Impact and Reach Expanding to Philadelphia will allow ICW to reach more highrisk youth and potentially reduce ... View full answer

Get step-by-step solutions from verified subject matter experts