Characterize the types of investments that are most vulnerable to political risk. Characterize those that are least

Question:

Characterize the types of investments that are most vulnerable to political risk. Characterize those that are least vulnerable. What factors influence an investment’s vulnerability? On a scale of 1 to 10, with 10 being the highest, how vulnerable is the Kashagan consortium to political risk?

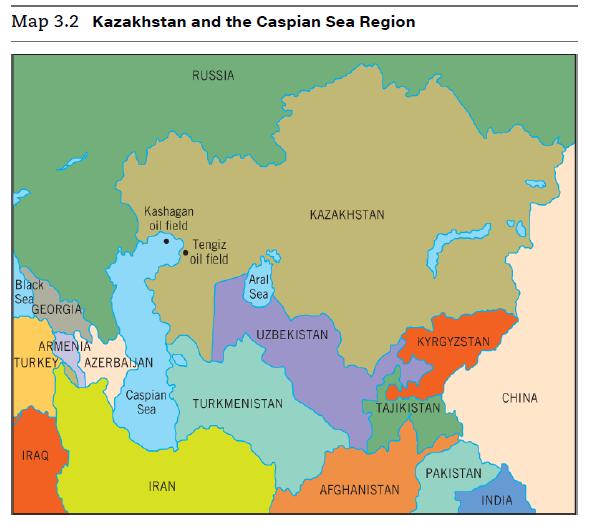

With an estimated 13 billion barrels of oil—making it the fifth largest reservoir in the world and the largest discovery in 30 years—you’d think that rights to develop the Kashagan oil field in Kazakhstan would bring a smile to any oil executive’s face (see Map 3.2 ). Instead, it has produced nothing but headaches for the Western oil companies involved.

The Kazakhstan Soviet Socialist Republic was part of the Soviet Union for most of the twentieth century. The Soviet Union was aware of the field’s potential, but chose to avoid the technical difficulties of offshore drilling there in favor of its more easily exploited Siberian oil deposits. When the Soviet Union disintegrated and Kazakhstan gained its independence in 1991, the new country lacked the technology and management skills to develop the field, for most of the available talent was Russian.

Accordingly, it offered exploration rights to Western oil companies using a production sharing agreement (PSA). PSAs are common in the oil industry. The companies bear all the costs of exploring, developing, and operating the oil field, but are allowed to recover all of their costs before having to share any revenues with the host government.

In 1997, a consortium of oil companies—Shell, BP, Total, Mobil (now part of ExxonMobil), ENI of Italy, Statoil of Norway, and the BG Group of the United Kingdom—won the rights to develop Kashagan under a production sharing agreement signed with the Kazakh government. (In 2003, BG dropped out of the project; the state-owned Kazakh company KazMunaiGas (KMG) bought half of BG’s share, with the other half being split among the other partners.) The consortium hoped to be pumping 250,000 barrels of crude oil per day by 2011 and 1.5 million barrels a day by 2019.

Originally the companies selected Shell to serve as the lead operator. But after a series of misadventures with a drilling barge that Shell had used in Nigeria and proposed to transport to the Caspian Sea, the other partners demanded a new operator. ENI was the compromise choice.

The challenges facing ENI were numerous. The Caspian Sea freezes over five months of the year because winters in the region are cold and its waters are shallow in the Kashagan region. Ice floes and pack ice driven by fierce north winds would be constant threats to any drilling rig. ENI’s solution to the challenges of drilling in these difficult conditions was to build a man-made island 50 miles offshore, surrounded by curved reefs to protect it against the destructive power of the Caspian Sea, on which the rigs would operate. Over 4 million tons of rock would be needed to build the island complex. This approach was initially rejected by Kazakh authorities, as it would delay production until 2005. However, after a year’s delay, they granted approval, agreeing to a revised start date of 2008, although they also announced the government would fine the oil companies’ \($50\) million each year production was delayed beyond the original 2005 start date.

While the sea is shallow, the Kashagan deposits lie 12,000 feet below the Caspian’s seabed. Extremely high gas pressure plagues the field—500 times that at sea level—requiring the use of expensive stress-resistant pipes and sophisticated compressors to reinject these gases back into the ground. And the oil flowing from Kashagan’s reservoirs is full of deadly hydrogen sulfide gas. Crude oil with a hydrogen sulfide concentration of over 1 percent is considered to be “sour.” Sour oil is more expensive to refine into gasoline, and more of the barrel tends to be used to make lower-priced products like fuel oil and diesel fuel. The hydrogen sulfide concentration of Kashagan’s oil was 15 percent; 3 percent would be considered extremely high. The high levels of hydrogen sulfide substantially increased the dangers facing the drilling and operating crews, forcing ENI to invest heavily in protecting its work force.

Employees on the rigs are subjected to daily evacuation drills. Gas detectors and oxygen canisters are nearby, as are high speed boats to evacuate the workers should an emergency arise. The facilities on the island had to be redesigned when it was determined that the living quarters were too close to the compressors that injected the hydrogen sulfide back into the reservoir, making even minor leaks a major danger.

ENI had budgeted \($10\) billion to develop the Kashagan field. However, in mid-2007, ENI announced large budget overruns—the estimated development costs ballooned to \($19\) billion—and pushed back the expected start of production to 2010. ENI blamed the cost overruns on escalating daily lease rates for drilling rigs, soaring steel prices, and shortages of skilled personnel, including project managers and oilfield engineers.

Needless to say, the Kazakh government was not pleased with this news.

The cost overruns and project delays reduced the magnitude of the revenues it had anticipated, as well as postponing their arrival. In August 2007, the Kazakh government demonstrated its displeasure by suspending the consortium’s operating licenses for three months on environmental grounds, arguing that ENI had failed to protect the breeding grounds of the endangered beluga sturgeon and harmed the local seal population. It also threatened to investigate the consortium for customs violations and for violating the country’s fire safety regulations.

The Kazakhi parliament passed a law allowing the government to abrogate contracts with foreign oil companies if it were in the national interest.

In September, Kazakh officials demanded that the state oil company, KMG, should be made co-operator of the Kashagan field, since ENI had demonstrated an inability to fulfill the terms of the original contract. After several months of negotiations, the dispute was settled in January 2008.

The Western oil companies agreed to allow KMG to double its stake in the consortium to 16.6 percent for \($1.8\) billion, a bargain basement price given the revenues that the Kashagan field is expected to generate for the next 40 years. In addition, the consortium agreed to increase the royalties paid directly to the Kazakh government by an additional \($2.5\) billion to \($4.5\) billion, depending on the future price of oil. These changes were made in part to compensate the government for agreeing to push the start date out to 2013.

Step by Step Answer: