In the two decades to 2017, Chinas share of global merchandise exports almost tripled, rising from 4.7

Question:

In the two decades to 2017, China’s share of global merchandise exports almost tripled, rising from 4.7 per cent to 12.8 per cent. However, this trend did not reflect China’s exports of rare earth minerals, which are commonly used in high-tech products. This is a group of 17 minerals, used in a wide range of products such as hybrid cars, weapons, flat-screen TVs, mobile phones, mercury-vapour lights and camera lenses. As the elements associated within these minerals are ‘relatively/ moderately abundant’, meaning less common than elements like oxygen, silicon, aluminium and iron (which together account for approximately 90 per cent of the Earth’s crust), they are called ‘rare earth’ minerals.

China’s dominant global position in the production of rare earths took a hit in 2015 as the World Trade Organization (WTO) forced the nation to abolish their restrictive export quotas for rare earth products. Under the guidelines set by the WTO, although sales of rare earth products required an export license, this was no longer associated with fixed quotas. China had previously sought to protect the value of rare earths by imposing export quotas in 2009, but the rise in computer and high-tech products fuelled supply concerns and quickly prompted other nations to start producing rare earth products to take advantage of this market opportunity. As such, the US was quick to open and develop new mines in search of rare earth minerals and a number of countries, including Japan, started to invest in initiatives to recycle rare earths.

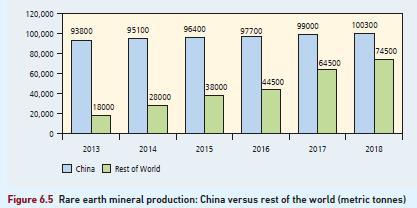

A primary reason for China to impose quotas on rare earth mineral exports was a trade dispute with Japan. Japanese multinationals who required high volumes of rare earth minerals, such as Hitachi and Mitsubishi, started to re-design some of their products to reduce reliance on these mineral components. Although China’s imposition of quotas provided it with market power and political leverage, the state struggled to exploit their position over the long run as the rest of the world picked up the slack and broadening the global supplier base of these minerals (Figure 6.5).

When other nations, and multinationals, started to invest in the production of rare earth minerals, Beijing was quick to claim that there was a need to conserve a scarce resource and limit environmental damage that could be caused by opening new mining sites. However, China did not impose restrictions on either the production or use of rare earths by firms within the domestic market. Initially, China’s 2009 quota was challenged by the US in 2012 via the WTO and the EU and Japan were quick to join forces with the US’s complaint. Historically, up until the late 1990s the US produced and supplied their own rare earth minerals, but production declined as low-cost Chinese firms started to dominate the global market, and China decided to take control of the rare earth market by forcing Chinese firms to merge into state-owned groups. The export quota that was placed by China in 2009 came at an economically sensitive period, as following the 2008 financial crisis many nations were seeking to boost exports to tackle unemployment concerns.

When other nations, and multinationals, started to invest in the production of rare earth minerals, Beijing was quick to claim that there was a need to conserve a scarce resource and limit environmental damage that could be caused by opening new mining sites. However, China did not impose restrictions on either the production or use of rare earths by firms within the domestic market. Initially, China’s 2009 quota was challenged by the US in 2012 via the WTO and the EU and Japan were quick to join forces with the US’s complaint. Historically, up until the late 1990s the US produced and supplied their own rare earth minerals, but production declined as low-cost Chinese firms started to dominate the global market, and China decided to take control of the rare earth market by forcing Chinese firms to merge into state-owned groups. The export quota that was placed by China in 2009 came at an economically sensitive period, as following the 2008 financial crisis many nations were seeking to boost exports to tackle unemployment concerns.

The Chinese dominated global markets in 2013 when they produced almost 80 per cent of rare earth minerals. This declined to reach 40 per cent by 2018. In an attempt to take back some control over the market and push up prices, China decided to limit the total production of rare earth minerals in the second half of 2018. A production limit of 45,000 tonnes was set, representing a five-year low. Given the recent US and China trade war, arguably this was an indirect blow aimed at the US, as 45,000 tonnes of rare earths is only enough to supply China’s domestic market needs. There were indications that this attempt to take back some control of the market was working. The price for one key rare earth mineral, PrNd Oxide, began to rise in 2019. But the evidence overall is mixed with some rare earth minerals showing price increases and others showing declines.

Overall, history tells us that when the supply for essential materials and components like rare earth minerals becomes too heavily dependent on one country, in this case China, other nations mobilise to rebalance the market. The dynamics of international trade are driven by actions and reactions, as nations seek to gain temporary local advantage over others through trade policy, or defend local interests against the policies of others.

Step by Step Answer:

International Business

ISBN: 9781292274157

8th Edition

Authors: Simon Collinson, Rajneesh Narula, Alan M. Rugman