Do high-technology products invented by American companies result in a trade surplus for the United States? Not

Question:

Do high-technology products invented by American companies result in a trade surplus for the United States? Not necessarily. Consider the case of the iPhone. Designed and marketed by Apple Inc. (a U.S. company), the iPhone functions as a camera phone, including visual voicemail, text messaging, a portable media player, and an Internet client, with e-mail, web browsing, and Wi-Fi connectivity. It obviously is a high-technology product. However, instead of contributing to a trade surplus for the United States, the iPhone results in a bilateral trade deficit with China. This is because China ships to the United States all iPhones purchased by American consumers.

In 2009, the iPhone increased the U.S. trade deficit with China by $1.9 billion according to conventional trade statistics. How is this possible? Conventional ways of measuring trade flows do not acknowledge the intricacies of global commerce where the design, manufacturing, and assembly of goods often encompass several countries. The weakness of the conventional approach is that it considers the full value of an iPhone as a Chinese export to the United States, even though it is designed by a U.S. company and is manufactured largely from components produced in several Asian and European countries. China's only contribution to the value of an iPhone is the final step of assembling and shipping it to the United States.

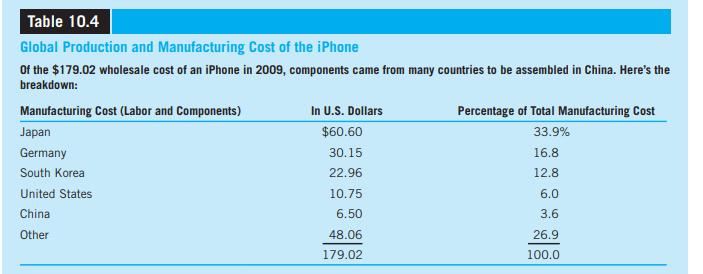

As seen in Table 10.4, the entire $179.02 wholesale cost of an iPhone that was shipped to the United States in 2009 was credited to China's exports, even though the value of work performed by Chinese assemblers amounted to $6.50, or just 3.6 percent of the total. This resulted in an exaggeration of the bilateral trade deficit of the United States with China. If China was credited with producing only its portion of the value of an iPhone, its exports to the United States for the same number of iPhones would have been a much smaller figure. This is why many economists feel that breaking down imports and exports in terms of the value added from different countries is a more accurate way of measuring trade statistics than the conventional method.

Conventional trade statistics tend to inflate bilateral trade deficits between a country used as an export processing zone by multinational firms and its destination countries. In the case of the iPhone, China only accounted for 3.6 percent of the U.S. $1.9 billion trade deficit, the remainder stemming from Japan, Germany, and other countries that produced components used to make the iPhone. By inflating the bilateral trade deficit with China, conventional trade statistics add to political tensions simmering in Washington, DC, over what to do about China's allegedly undervalued currency and unfair trading practices.

Conventional trade statistics tend to inflate bilateral trade deficits between a country used as an export processing zone by multinational firms and its destination countries. In the case of the iPhone, China only accounted for 3.6 percent of the U.S. $1.9 billion trade deficit, the remainder stemming from Japan, Germany, and other countries that produced components used to make the iPhone. By inflating the bilateral trade deficit with China, conventional trade statistics add to political tensions simmering in Washington, DC, over what to do about China's allegedly undervalued currency and unfair trading practices.

What do you think? Given the limitations of balance of payments statistics, are they of much use to policy makers?

Step by Step Answer: