The town of Verey, Switzerland, perches among the vineyards above Lake Geneva. Wealthy retirees take in Alpine

Question:

The town of Verey, Switzerland, perches among the vineyards above Lake Geneva. Wealthy retirees take in Alpine vistas as they pass their afternoons strolling along the waterfront. The most exciting event is the annual grape harvest. Silicone Valley and the hubbub of high tech seem worlds away. On the edge of town, however, stands the glass and steel global headquarters of Nestlé, the world’s largest food producer.

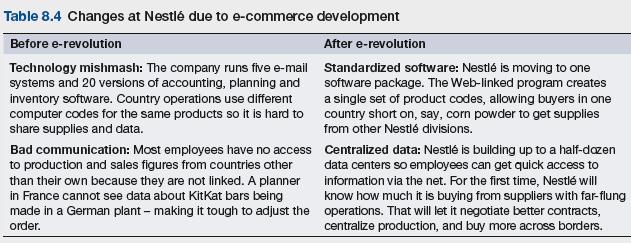

This setting has now become the epicenter of one of Europe’s most ambitious e-commerce initiatives as Nestlé

undertakes a plan to make the company more agile, more responsive to its customers, and more profitable. Over the next three years it will invest as much as US$1.8 billion in a phased development plan. The company will continue to expand its use of the Internet and Web, acquire additional specialized software and solutions, build data centers, and work toward creating a coherent global information system. Peter Brabeck-Lemathe, the company’s chief executive, calls the process an ‘e-revolution’ – albeit one that will take several years to complete.

He has commented that ‘This might sound slow for Silicon Valley, but it’s very fast’ for a company like Nestlé.

The company

Henri Nestlé founded the company in 1867 in order to market the baby formula he had developed. In 1938, Nestlé scientists were the first to produce instant coffee.

These two products fueled much of the company’s growth for its first century. Twenty years ago Nestlé began a US$40 billion buying spree, acquiring a number of companies including Friskies in 1985, saucemaker Buitoni in 1988, and Perrier in 1992.

Now, with 1999 revenues of US$46.6 billion, 509 factories in 83 countries, 230,000 employees, and over 8,000 products, Nestlé is the world’s leading food and beverage company. However, profits margins have been low compared to industry standards, and the stock price has stagnated.

Nestlé is involved in all phases of the food industry, from buying raw materials such as cocoa beans to processing, packaging, marketing, and selling products. Many food items remain local products. As Brabeck says: ‘You can’t sell a Bavarian soup to a Taiwanese noodle-lover.’ The company thus must make adjustments to product lines, packaging, pricing, advertising, etc. to suit the demands of each of its many markets. Nestlé’s size and complexity, as well as the diversity of environments in which it operates, create problems in all phases of operations, with substantial duplications of effort and difficulties in getting all of the required information to some decision makers.

Nestlé has viewed the improvements in intercompany and intracompany communications made possible by the Internet and the Web, and the software available for use in e-commerce, as providing great potential for reducing costs in everything from obtaining materials and supplies to marketing. It also makes feasible certain types of restructuring that should lead to improved responsiveness and control. ‘For big companies like us, the Internet is particularly good because it shakes you up,’ says Mario Corti, Nestlé’s chief financial officer and head of its Internet offensive. In its e-commerce initiatives, Nestlé must practice a delicate balancing act: using the net to both reduce transaction costs and gain economies of scale while still catering to a variety of cultural preferences.

Nestlé’s early e-commerce initiatives, coupled with restructuring efforts, led to an increase in net profit of almost 35% in the first half of 2000 (to US$1.7 billion). Now the company is undertaking a major additional effort in e-commerce.

Expanding e-commerce initiatives

In June 2000 Nestlé signed a US$200 million contract with German-based SAP to provide support in this effort. SAP is the world’s largest provider of ERP (enterprise resource planning) software and solutions designed to support a broad range of integrated management systems including financials, supply chain management, e-procurement, customer relationship management, etc. For SAP, it was the largest sale ever. For Nestlé, the objective is to streamline the company’s operations and give farflung employees quick access to information from around the globe. This should enable Nestlé to better leverage its size by tying together long-independent national fiefdoms.

Expected results are as shown in Table 8.4.

Although Nestlé is a consumer-driven company, most of the changes will be invisible to diners sipping Perrier or kids munching Nestlé Crunch bars. But behind the scenes, the way Nestlé buys, manufactures, and delivers its products is going digital. The company is a founder of online food-supply marketplaces Transora and CPGmarket.com, which aim to use the Web to streamline purchasing.

The emphasis, though, will not be on slashing raw material prices or eliminating distributors. Instead, Nestlé wants to link its disparate operations, partner with suppliers to cut waste, and move its food products more quickly from farm to factory to the family dinner table. Rather than desiring to squeeze suppliers, these actions are designed to increase the company’s internal productivity.

Nestlé’s reinvention is a work in progress. The company’s margins, while improving, remain a third lower than those of competitors H. J. Heinz, Cadbury, or Procter &

Gamble. The giant SAP deal is at least three years away from giving all Nestlé employees access to information from other countries’ divisions. Transora and CPGmarket.

com are only now beginning operations, and online marketplaces in many other industries are encountering severe teething problems.

That is where the Web comes in. The first order of business has been linking to retailers. Since July, store owners in the United States have been able to order Nestlé

chocolates and other products online at NestléEZOrder.com. The benefit for Nestlé: the system cuts out expensive manual data entry and slashes processing costs for each order from US$2.35 to 21 cents. Similar initiatives are on tap for other countries, which could trim as much as 20% from the company’s US$3 billion in yearly worldwide logistics and administrative costs.

The net helps cut inventories, too. In the past, when Nestlé held promotions it had to guess at demand. By linking up electronically with its retail partners it can now adjust production quickly. In Britain, supermarket chains Sainsbury and Tesco send in daily sales reports and demand forecasts over the Web to Nestlé headquarters, while Nestlé managers check inventory levels on the supermarkets’ computer systems. ‘It’s been a revolution in the way we work together,’ says Tom McGuffog, director of e-business at Nestlé UK.

Nestlé is seeing similar results from sharing information online inside the company. Pietro Senna, a buyer for Nestlé Switzerland, was recently having trouble getting kosher meat. He posted a message online, and a colleague in the United States found him just the right supplier – in Uruguay. The time savings are immense.

Each country’s hazelnut buyer, for example, used to visit processing plants in Italy and Turkey. Hazelnuts, a key ingredient in chocolate bars, are prone to wild price swings and uneven quality. But after Senna stopped by some Turkish plants he posted his report on the Web – and within a week 73 other Nestlé buyers from around the globe had read it, saving them the trouble of a trip to Turkey. ‘For the first time, I get to take advantage of Nestlé’s size,’ he says. When leveraged, that size can slash procurement costs. Until recently, Nestlé had 12 buyers throughout Europe, dealing with 14 suppliers of lactose, an ingredient in infant formula and chocolate bars. By linking via the net, the company has been able to cut its suppliers to just four. ‘We can only do this because of online information, ’Senna says. Lactose costs have come down by as much as 20%.

Nestlé’s Web charge is being led by its dairy farm in Carnation, Washington, USA. Nestlé’s US CEO Joe Weller asks workers how to unify Nestlé. The answer: e-business.

If the US division leads, the rest of the giant is likely to follow.

The sheer weight of the US operation has wallop: it booked more than US$10 billion in sales last year, nearly a quarter of the company’s total. If the US division is quarterbacking the effort, Brabeck is its chief cheerleader. He does not have a computer in his office – e-mails have to go through his secretary. And far from passing his leisure time surfing the net, 56-yearold Brabeck spends his weekends climbing the Alps that tower over Vevey. But he was an early backer of e-tailing experiments the company participated in. Those trials were eventually shelved, but Brabeck says they demonstrated the power of technology and the net. ‘This opened my eyes,’ he says. Nestlé’s disparate Internet ventures present a mountain of opportunity that will require all the strength and savvy Brabeck can muster. He does not underestimate the challenges ahead. But he does not seem fazed either.

Some comments on Nestlé’s subsequent performance

Nestlé appears to be making substantial progress with its e-commerce initiatives, streamlining and integrating operations, and overhauling the information technology systems. Information systems improvements have given management the data they need to compare performance of units worldwide, and to identify those needing help. They have also enabled the company to avoid some of the costs of highly decentralized buying and logistics. Since 2001, the company has realized US$1.5 billion in cost savings, and expects an additional US$2.5 billion savings by 2006 (Matlack, 2003). While still trailing the operating margins of Unilever and Kraft, Nestlé’s have risen by almost 50% in the past five years (Ball, 2004).

The company has made three acquisitions, at a total cost of US$15.5 billion to increase its presence in the United States (Weintraub and Tierney, 2002). The company is still pursuing sales growth and is keeping its broad and diverse product line with about 8,000 brands (Matlack, 2003).

Under Mr Brabeck’s direction, Nestlé has continued to focus on improving IT, has purchased higher margin businesses, and has trimmed its portfolio of lower-margin product lines. The company is enjoying a fifth year of strong profit growth, and its share prices have grown more rapidly than those of Unilever and Kraft (Simonian, 2007).

Questions

1. Evaluate Nestlé’s use of the Internet and the Web to this point. How will its marketing operations be enhanced?

2. What other uses of the Internet should Nestlé

explore?

3. Does the signing of a contract for such major software and solutions development with SAP seem appropriate at this stage? Should the company take one step at a time rather than attempt to do so much at once?

4. Will the Internet and the Web revolutionize international marketing? Explain.

5 What are the advantages and disadvantages of having some 8,000 brands?

Step by Step Answer:

International Marketing And Export Management

ISBN: 9781292016924

8th Edition

Authors: Gerald Albaum , Alexander Josiassen , Edwin Duerr