After serving in the less demanding position as a traffic court judge, Judge Victoria Pratt was assigned

Question:

After serving in the less demanding position as a traffic court judge, Judge Victoria Pratt was assigned to the city of Newark, New Jersey’s Part Two criminal court. Part Two is a court that handles low-level, nonviolent offenses. It was an undesirable assignment for a judge due to the large volume and difficulty of the cases and to significant frustration as the same defendants returned time after time. It was not just the cases that made the assignment disagreeable, but also the morale and mindset of the court employees. Judge Pratt (2016) explains: “[T]he attitudes there were terrible. And the reason that the attitudes were terrible was because everyone who was sent there [to work at the court] understood they were being sent there as punishment. The [police] officers who were facing disciplinary actions . . . the public defender and prosecutor felt like they were doing a 30-day jail sentence on their rotation.”

At the same time Judge Pratt took on this challenging assignment, the city of Newark was initiating a pilot program in the Part Two criminal court aimed at changing the system. This pilot program, Newark Community Solutions, was modeled after the successful Red Hook Community Justice Center in southwestern Brooklyn, New York, created by the Center for Court Innovation (CCI), a nonprofit justice reform organization, and Judge Alex Calabrese. The Red Hook approach provides “rapid sanctions aimed at stopping the cycle of people going in and out of jail: community service, social services such as anger management and conflict resolution, or longer-term drug treatment” (Rosenberg, 2015).

Successful completion of the program meant avoiding jail time. Defendants were required to return to court frequently to discuss their progress and/or submit to mandatory urine tests. But if drug tests were failed or appointments missed, the resulting jail sentences would be considerably longer than the terms the defendants would initially have been given.

Judge Pratt visited Red Hook and was struck not only by what Judge Calabrese did, but how he did it.

He engaged directly with the defendants, sitting eye level with them instead of above, talking in plain, understandable language and congratulating them on even the smallest victories. He asked them about their intentions for the future and what they felt was best for them. Judge Calabrese was implementing the concept of “procedural justice” based on the concept that “an offender is more likely to do what the authorities tell him and refrain from committing further crimes if he feels that he is treated with respect and fairness—regardless of the judge’s ruling” (Rosenberg, 2015). To that end, the four tenets of procedural justice are neutrality (defendants trust that the process is impartial), respect (defendants must be treated with respect), understanding (defendants clearly understand what is going on, the consequences of the process, and what is expected of them), and voice (defendants have an opportunity to speak).

Judge Pratt had never witnessed those types of interactions in a courtroom. Energized, she embraced this new partnership and the resulting program, known as Newark Community Solutions, as an opportunity to change the culture of her newly assigned court.

An important aspect of Newark Community Solutions was to develop community trust and buy-in through the creation of “community courts.” Hearings were held to solicit input from members of the community regarding how they felt justice should function. The responses focused not on punishment but on helping defendants lead productive lives through such things as jobs and treatment for drug addiction. The people didn’t view the defendants as just criminals; they were members of the community, the kids who once played in the neighborhood parks. A community advisory board was created to maintain a dialogue and feedback between the community and the judiciary.

Because the program was new, services such as psychological screening, counseling, and therapy groups that were a cornerstone of the Red Hook program were not yet in place at Newark Community Solutions. Undeterred, Judge Pratt did what she could on her own, implementing the concepts of procedural justice and emulating the way Judge Calabrese interacted with defendants.

She led by example, training the court staff, attorneys, and police officers how to engage with court participants. She spoke to the defendants in her court with respect, explaining in simple language (in English and in Spanish) the charges against them, the consequences of those charges, and what was expected of them. She would require defendants to do nontraditional tasks, such as assigning defendants to write an essay about themselves, but with a twist—they were required to return to court and read it aloud. She believed the essays were a valuable way to give the defendants voice, to help her better understand them, and to provide a means for them to contemplate and respond to her deeper questions. Requiring the essays be read aloud encouraged them to take the assignment more seriously.

She shares the example of a man who came before her who had been addicted to drugs for 20 years.

She assigned him to write a letter to his son. When he read the letter aloud in court, it began, “My dear son who’s sitting in heaven, you were taken away far too soon at 16 years old and I haven’t been able to get right since.” Realizing they were “looking at more than a junkie,” the court saw instead a man who was numbing his deep grief with drugs and was now in a better position to more appropriately address the real problem (Fields, 2019).

It wasn’t long before the results of her actions began to pay off. Shortly after her takeover of Part Two, an older man came before Judge Pratt on heroin charges. Judge Pratt asked him how long he had been addicted. When he told her he had been addicted for 30 years, she began to quiz him on a personal level. “I wanted to get to the human side and not just the old, dried-up, drug-addict side,” she said, recalling the exchange.

She asked if he had a family. Yes, a son who was 32.

“Then you haven’t been a father to your son for most of his life,” Pratt stated pragmatically. The man started to cry. Under the old system, Pratt would have had to give him jail time; instead, she told him to come back in two weeks and secured a drug treatment program for him. Two weeks later, he showed up just as she had directed. “You showed me more love than I have for myself,” she recalled him saying.................

Questions

1. A positive environment is shaped by the degree to which people feel they are supported, appreciated, and encouraged for their roles. Discuss how Judge Pratt has or has not created this type of environment in her courtroom.

2. Providing structure is important to developing a constructive climate. This book lists the following three ways a leader provides structure; for each one, describe how it is applied in Judge Pratt’s courtroom.

a. Establish concrete goals

b. Give explicit assignments

c. Make responsibilities clear

3. As discussed in this chapter, “norms emerge as a result of how leaders treat followers and how followers treat each other. . . .When a leader brings about constructive norms, it can have a positive effect on the entire group.” Describe how Judge Pratt used this concept to change the culture in her courtroom, both with the court staff and with the defendants who appeared before her.

4. Cohesiveness, described as a sense of “we-ness,” may seem an odd fit with a criminal courtroom.

Reviewing the description of cohesiveness in the text, describe how that concept contributes to the constructive climate of Judge Pratt’s courtroom.

a. The text lists the following leadership actions for building cohesiveness. Which of these do you think Judge Pratt found most useful, and how did she apply them?

i. Create a climate of trust

ii. Invite group members to become active participants

iii. Encourage passive or withdrawn members to become involved

iv. Be willing to listen and accept group members for who they are

v. Help group members to achieve their individual goals

vi. Promote free expression of divergent viewpoints in a safe environment

vii. Allow group members to share leadership responsibilities viii. Foster and promote member-to-member interaction instead of only leader-to-follower interaction

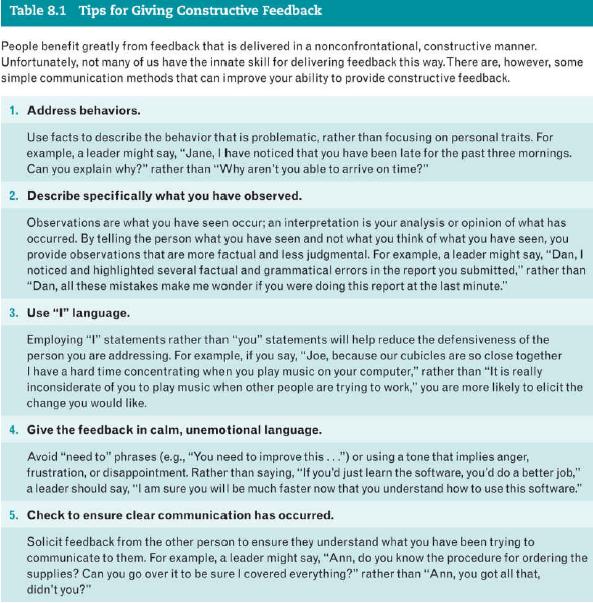

b. Table 8.1 provides a list of positive outcomes for cohesive groups. Identify and explain which of these apply to this case.

5. How did Judge Pratt apply the six essential factors of promoting standards of excellence to the cultural shift in the Part Two criminal court?

Step by Step Answer:

Introduction To Leadership Concepts And Practice

ISBN: 9781544351599

5th Edition

Authors: Peter G Northouse