New Orleans mayor Mitch Landrieu wanted to observe the 300th anniversary of his city in a way

Question:

New Orleans mayor Mitch Landrieu wanted to observe the 300th anniversary of his city in a way that would “build something that would make us better” (Winfrey, 2018).

The city was still rebuilding and recovering from the devastation of a recession, a major oil spill, and four hurricanes when Mitch was approached by a friend with the idea of removing the Robert E. Lee statue, one of four prominently placed statues around the city memorializing the Southern confederacy and its leaders. Mitch was born and raised in New Orleans, the son of white parents. He grew up in a diverse neighborhood surrounded by the richness of the culture of New Orleans. His father, a member of the Louisiana legislature, was one of the only people to vote against segregationist laws in the 1960s.

Initially, Landrieu shied away from the proposal, but started researching the history of the monuments— who had constructed them and to what purpose. Realizing this was an opportunity to heal a significant wound at an important time in the city’s history, he decided all four of the statues should be removed.

After almost two years of effort, significant controversy, and difficulty, the last statue came down on May 19, 2017. On that day, Mayor Landrieu delivered the following speech explaining why he felt this was so important for the City of New Orleans and its people: Thank you for coming.

The soul of our beloved City is deeply rooted in a history that has evolved over thousands of years; rooted in a diverse people who have been here together every step of the way—for both good and for ill. It is a history that holds in its heart the stories of Native Americans—the Choctaw, Houma Nation, the Chitimacha. Of Hernando De Soto, Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle, the Acadians, the Islenos, the enslaved people from Senegambia, Free People of Colorix, the Haitians, the Germans, both the empires of France and Spain. The Italians, the Irish, the Cubans, the south and central Americans, the Vietnamese and so many more.

You see—New Orleans is truly a city of many nations, a melting pot, a bubbling caldron of many cultures. There is no other place quite like it in the world that so eloquently exemplifies the uniquely American motto: e pluribus unum—out of many we are one. But there are also other truths about our city that we must confront. New Orleans was America’s largest slave market: a port where hundreds of thousands of souls were bought, sold and shipped up the Mississippi River to lives of forced labor, of misery, of rape, of torture. America was the place where nearly 4,000 of our fellow citizens were lynched, 540 alone in Louisiana; where the courts enshrined “separate but equal”; where Freedom Riders coming to New Orleans were beaten to a bloody pulp. So when people say to me that the monuments in question are history, well what I just described is real history as well, and it is the searing truth.

And it immediately begs the questions, why there are no slave ship monuments, no prominent markers on public land to remember the lynchings or the slave blocks; nothing to remember this long chapter of our lives; the pain, the sacrifice, the shame . . . all of it happening on the soil of New Orleans. So for those self-appointed defenders of history and the monuments, they are eerily silent on what amounts to this historical malfeasance, a lie by omission. There is a difference between remembrance of history and reverence of it.

For America and New Orleans, it has been a long, winding road, marked by great tragedy and great triumph. But we cannot be afraid of our truth. As President George W. Bush said at the dedication ceremony for the National Museum of African American History & Culture, “A great nation does not hide its history. It faces its flaws and corrects them.” So today I want to speak about why we chose to remove these four monuments to the Lost Cause of the Confederacy, but also how and why this process can move us towards healing and understanding of each other. So, let’s start with the facts.

The historic record is clear, the Robert E. Lee, Jefferson Davis, and P.G.T. Beauregard statues were not erected just to honor these men, but as part of the movement which became known as The Cult of the Lost Cause. This “cult” had one goal—through monuments and through other means—to rewrite history to hide the truth, which is that the Confederacy was on the wrong side of humanity. First erected over 166 years after the founding of our city and 19 years after the end of the Civil War, the monuments that we took down were meant to rebrand the history of our city and the ideals of a defeated Confederacy. It is self-evident that these men did not fight for the United States of America, they fought against it. They may have been warriors, but in this cause they were not patriots. These statues are not just stone and metal. They are not just innocent remembrances of a benign history. These monuments purposefully celebrate a fictional, sanitized Confederacy; ignoring the death, ignoring the enslavement, and the terror that it actually stood for.

After the Civil War, these statues were a part of that terrorism as much as a burning cross on someone’s lawn; they were erected purposefully to send a strong message to all who walked in their shadows about who was still in charge in this city. Should you have further doubt about the true goals of the Confederacy, in the very weeks before the war broke out, the Vice President of the Confederacy, Alexander Stephens, made it clear that the Confederate cause was about maintaining slavery and white supremacy. He said in his now famous “cornerstone speech” that the Confederacy’s “cornerstone rests upon the great truth, that the negro is not equal to the white man; that slavery—subordination to the superior race—is his natural and normal condition. This, our new government, is the first, in the history of the world, based upon this great physical, philosophical, and moral truth.”

Now, with these shocking words still ringing in your ears . . . I want to try to gently peel from your hands the grip on a false narrative of our history that I think weakens us. And make straight a wrong turn we made many years ago—we can more closely connect with integrity to the founding principles of our nation and forge a clearer and straighter path toward a better city and a more perfect union.....................

Questions

1. Some people argue that leadership has a moral dimension that moves people toward the common good. Do you think Mayor Landrieu’s speech has a moral dimension? If yes, what values is Mayor Landrieu promoting? What are the obstacles to his advocacy?

2. By removing the statues and through his speech, Mayor Landrieu takes a strong stand against dignifying symbols of the Confederacy. Do you feel his actions fostered a stronger sense of inclusion within the city of New Orleans? Discuss how different perceptions of the statues and their inherent messages may have affected different groups within the community.

3. The chapter discussed five barriers to diversity and inclusion: ethnocentrism, prejudice, unconscious bias, stereotypes, and privilege. In what ways were these statues symbolic of these barriers?

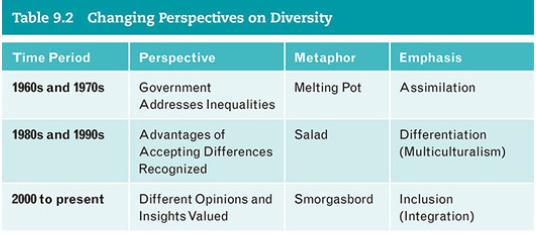

4. Table 9.2 describes different metaphors for diversity during different time periods. What is the metaphor and emphasis of Mayor Landrieu’s speech, and what are the implications of this approach for diversity and inclusion?

5. Consider the various symbols in your community, school, or workplace that you see every day. Select one or two and discuss the possible perceptions of each symbol to different members of your community.

Step by Step Answer:

Introduction To Leadership Concepts And Practice

ISBN: 9781544351599

5th Edition

Authors: Peter G Northouse