When a UK government department lost computer discs carrying the personal data of 25m people members

Question:

When a UK government department lost computer discs carrying the personal data of 25m people – members of 7m families in receipt of child benefit – in 2008, the incident was blamed on mistakes by junior officials. But a report just published on the debacle focuses its criticism not so much on individuals as on the ‘unsuitable organisational design’ of Her Majesty’s Revenue and Customs (HMRC), the department formed by the merger of the Inland Revenue and Customs & Excise three years before.

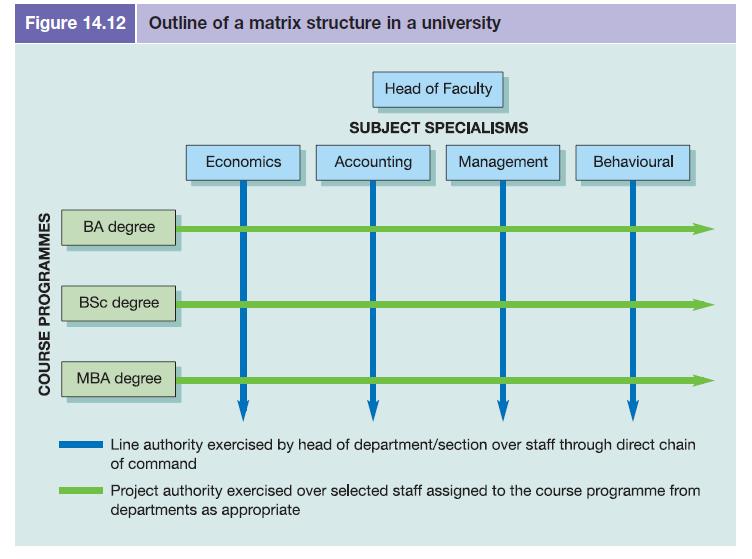

In the report of the investigation Kieran Poynter, chairman of City of London professional services firm PwC, expresses dismay at HMRC’s ‘muddled accountabilities’. In a swipe at the complex structure adopted for the 2005 merger, he says HMRC should have opted for a traditional, hierarchical structure: ‘[HMRC] is not suited to the so-called “constructive friction” matrix type organisation [that was] in place at the time of the data loss.’

So did HMRC really get it so wrong – and if so, why?

Both outside and inside HMRC, the management structure has been condemned. Even before the discs were lost, at least one professional institute – the tax faculty of the ICAEW, the UK chartered accountants’

body – blamed the ‘matrix management’ for lack of accountability, ownership of issues and clarity of vision. Soon after, a Cabinet Office report highlighted the ‘proliferation of committees’ at HMRC and criticised ‘the complex management structure’. At the time of the merger, however, HMRC’s top managers faced a traditional management problem of finding a way to integrate two entities without forcing one partner to mould itself to the other. They had two big organisations with different cultures: Inland Revenue was pragmatic and intellectual; Customs & Excise more confrontational. Costs had to be cut 5 per cent a year, with the consent of the unions and without alienating staff.

Around the time the HMRC was formed, Sir David Varney, the chairman (a senior industrialist who had worked at Shell, British Gas and BT) explained that senior managers’ responsibilities would not correspond with the former structures of the two legacy organisations, so enabling a new culture to develop. ‘We didn’t want an organisation that was split along lines of customers, operations or policies or infrastructure,’ he said. But was the matrix structure a fundamental flaw? The idea of a grid-like structure with multiple reporting lines first became popular in the 1970s for encouraging speed and innovation. At best, it helps top management understand the consequences of a course of action. But it has often been criticised for causing loyalty clashes and turf battles.

Professor Nelson Phillips, head of the organisation and management group at Tanaka Business School at Imperial College, London says matrix structures remain essential for multinationals. But he says a hierarchical structure has advantages for transactionprocessing organisations such as HMRC that need clear lines of communication. He suspects the adoption of a complex structure in cases such as HMRC might be a way of avoiding hard decisions: ‘Who is the boss? You can both be the boss in a matrix,’ he says. In the aftermath, HMRC has moved to a simpler structure that makes responsibilities clear. But in the long run, creating a common culture may prove a hard task.

Discussion questions

1. What lessons can be drawn from the article about the importance of organisational structure?

2. Why might the management of the newly created HMRC have chosen a matrix style (as shown in Figure 14.12), rather than a hierarchy? Explain the benefits and drawbacks of each for both employees and for the government.

Step by Step Answer:

Management And Organisational Behaviour

ISBN: 9780273728610

9th Edition

Authors: Laurie J. Mullins, Gill Christy