Of all the things Dave Gray worried about when he branched out overseas, tripe never entered the

Question:

Of all the things Dave Gray worried about when he branched out overseas, tripe never entered the equation.

Gray, founder and chairman of Xplane, a consulting and design firm based in Portland, Oregon, acquired a small firm in Madrid in late 2006, hoping to establish a European outpost and break into Spanish-speaking markets worldwide. Gray was eager to establish rapport between his Spanish and American staff members, and face-to-face meetings seemed like the best way to forge a bond. But during one dinner meeting in Madrid shortly after the acquisition, a visitor from Xplane’s St. Louis office refused to sample the tripe—considered a delicacy in Spain—and proceeded to make crude jokes about it.

It was a minor incident, but only one in a series of minor incidents that ultimately created tensions between the six employees in Xplane’s Madrid office and the 45 in its U.S. offices. “I expected to come in and say, ‘This is how we do things,’” says Gray, who relocated to Madrid to oversee the transition. But he quickly learned that the Madrid and American offices were separated by more than just an ocean.

Most companies have a standard formula for team building: Spring for an annual off-site, throw in a few happy hours and a holiday party, and hope for chemistry.

That approach may suffice when employees work under the same roof or even in the same country. But in a global workplace, misunderstandings and resentments can pile up, says Anil Gupta, a professor at the University of Maryland’s Robert H. Smith School of Business and co-author of The Quest for Global Dominance: Transforming Global Presence into Global Competitive Advantage. The result, all too often, is an us-against-them mentality that makes the already challenging task of running a global organization much more difficult. Small companies, Gupta says, need to establish guidelines early, before tensions start to rise.

At Xplane, the culture clashes were starting to hurt morale. Gray noticed, for example, that some Spanish staff members grumbled when they learned that they had been excluded from e-mails sent to everyone in the two U.S. locations. The exclusion sent a clear message to the Spanish staff: You’re not one of us. “They would always forget there was a third office,” says Stephen O’Flynn, an Irish citizen and a project manager in the Madrid office.

Gray knew he had to make changes. “These cultural aspects don’t show up in numbers,” he says. “But a good culture is the fuel that keeps things going.” He told employees that too much information is better than not enough and that seemingly minor statements could be misinterpreted. Meanwhile, Xplane’s CEO, Aric Wood, asked the Madrid staff members to fill out surveys about their experiences, then discussed the results with them during one-on-one sessions. . . .

Lack of communication was a major complaint.

“Not only did they feel distant, but technology was a major obstacle,” Wood says. To make communicating easier, Xplane switched to Web-based phone service;

now, co-workers dial only four numbers to call one another instead of 13. Wood set up a wiki with pictures of employees from all three offices. O’Flynn became an unofficial ambassador to the U.S., going out of his way to call colleagues in Portland and St. Louis for input and urging his office mates to do the same. “I did a lot of brokering to get people talking,” he says.

The technology has improved communication, but it’s no substitute for face time, Wood says. Instead of spending money on a one-off team-building trip, Xplane started a year-round employee exchange program. Last year, the company rented apartments in Madrid and Portland and spent $20,000 flying employees back and forth for weeklong visits. About 16 employees have crossed the Atlantic. “We tried to close the gap through technology,” Wood says, “but ultimately we had to buy a lot of airline tickets.”

Of course, there is no one-size-fits-all solution for building an effective global team. Part of the problem is that each country has its own cultural peccadilloes. In China, for example, many employees are reluctant to disagree with their managers or assume leadership roles—

a trait linked to the legacy of the Cultural Revolution of the 1960s and 1970s, when speaking out was dangerous.

By contrast, companies moving into India often contend with ego clashes and power struggles, according to Gupta, who researched more than 200 companies for his book. “People in India, especially in tech companies, believe they are just as competent as those in the United States,” he says. That’s a problem if their American counterparts see them as second class.

Questions for Discussion

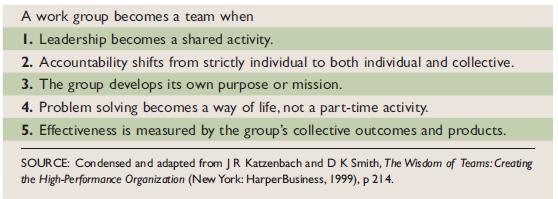

1. Using Table 11–1 as a guide, what did Xplane have to do to create a team when the Madrid firm was acquired? Explain.

Table 11-1

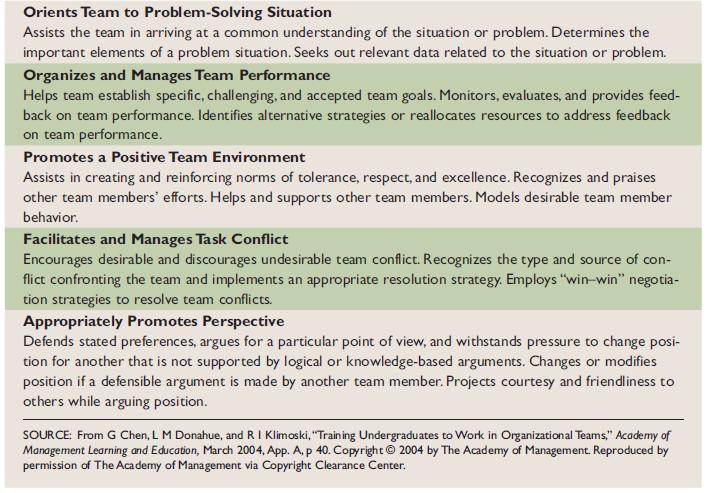

2. Should Xplane’s employees have been instructed ahead of time in both the cross-cultural competencies back in Table 4–4 and the teamwork competencies in Table 11–3? Explain how it should have been done.

Table 11-3

3. How important is trust with this sort of international virtual team? Explain how you would have established trust more quickly.

4. Which type of cohesiveness, socio-emotional or instrumental, is more important in this type of team building? Explain.

5. What advice would you give Xplane’s CEO Aric Wood about managing a virtual team, team building, and team leadership?

Step by Step Answer: