Health care systems face challenging prospects. These include ageing populations and a continuing growth in expenditures on

Question:

Health care systems face challenging prospects.

These include ageing populations and a continuing growth in expenditures on long-term and chronic conditions such as diabetes. There is pressure on financing, whether the basis of funding is private, insurance based or public expenditure. At the same time, hospitals are experiencing increases in emergency admissions and pressures on bed occupancy. Across the world, health care professionals and others are seeking to innovate in response to these challenges.

Of course, the position varies across the world and between countries, not least in relation to the issue of development, but changes in health systems are a key feature of today’s world.

In the United Kingdom, growth in health expenditure has been slower overall since 2011 but is now planned to grow at a higher rate. Conversely, UK public expenditure on social care has reduced, in real terms, between 2008 and 2016. At the same time, experience indicates that in periods of high growth in health expenditure (for example, 6 per cent pa), productivity growth is low, whereas when health expenditure growth is lower, productivity growth is higher. In the UK, patients with long-term and chronic conditions comprise 12 per cent of the population but consume nearly 50 per cent of health and care expenditure.

Approximately one third of all hospital beds are occupied by patients whom clinicians have assessed as medically fit to be discharged. The key limitation is how to organize ongoing care in the community and at home. This is costing hospitals £2.8 billion each year.

It needs to be noted that reducing this problem is not mainly about finance. We know that elderly patients lose muscle mass while in hospital and potentially this impacts significantly their quality of life. In addition, there is the risk of infection in hospital, and waiting to be discharged and get to their home is likely to be an experience many will view as an issue.

So, there is increased focus on how best to deliver care to differing segments, including specialized care for long-term conditions such as diabetes and strokes.

There is a trend towards setting up ‘integrated care’ –

enabling care to be more effectively coordinated along ‘care pathways’ and ensuring that key enablers are in place. These enablers include: effective information decentralized to care practitioners; effective payment mechanisms that provide a flow of funds to where expenditures are incurred; effective governance; and leadership of change.

There are two basic models of care. The first is a community-based model that builds on and extends primary and community care in order to avoid hospitalization.

The second focuses on building hospital care into a more fully integrated system, within which hospitals and other providers combine to deliver an ‘end-to-end’ approach to the delivery of care. Examples include many health care systems in the UK, such as those in Torbay, Sheffield Teaching Hospitals, Newcastle upon Tyne, Imperial College, Guys and St Thomas NHS Trust. Examples elsewhere include:

Montefiore in the Bronx, New York; Ribera Salud in Valencia, Spain; and the Camden Coalition, New Jersey.

There are versions of these models also in New Zealand, Denmark and Canada.

The economic case for integrated care is clear enough. Assume that primary care represents 10 per cent of the cost of a health system; hospital care would account for 50–60 per cent of health expenditure, the remainder being spent in the community, including ambulance and paramedic services. Therefore, a 30 per cent increase in primary care would require 3 per cent of the systems cost. Achieving a 20–30 per cent reduction in non-elective hospital admissions (normally 40–50 per cent of hospital spend) could deliver savings in the total system of between 5–9 per cent. Integrated care models focus on ensuring a more optimal organization of care across the system, rather than approaching the problem in terms of the optimal organization of each element considered separately.

Three fundamental building blocks are essential to the success of innovations of this type:

1. A focus on understanding and meeting the health needs of key population segments – for example, meeting the needs of elderly people and of those with chronic or long-term and complex conditions.

2. Changes in the health care delivery model to emphasize patients and to coordinate care, embracing multidisciplinary teams.

3. Five enablers of change need to be in place –

namely, payment models aligned to integrated care, information flows to support patient self-management, care delivery performance management and payment, governance arrangements to support long-term change management and professional leadership and management development focused on facilitating the necessary shift to a more planned and multidisciplinary model of care.

Progress here will be based on several characteristics of success in this field. First, there needs to be effective alignment around the common purpose of delivering integrated care. Second, it is important to put in place appropriate governance arrangements. Various stakeholder groups need to play an effective role in these arrangements, including professionals working in primary care, community care and hospitals, senior leaders from the health care providers involved and senior staff from the organizations providing the finances. Of course, a means must be found for ensuring the patients’ views and local community views and preferences are sought and considered. Third, there is the need to ensure that real change is delivered.

Montefiore and Ribera Salud demonstrate the important role of primary care in these innovations, but hospitals also have a vital role. They typically organize and manage the whole system leading the work to define standardized care pathways across the system and invest in estates information and provide the operational management of risks in the system.

On the face of it, hospitals have the most to lose from innovations of this kind because funds that are currently part of the hospital budget must now flow to other parts of the system. But, integrated care provides both more effective care for many patients and can lead to savings in the hospital, which would fund the necessary flow of funds. Moreover, do hospital staffs welcome a situation in which a third of beds are occupied by people they are not treating? Evidently there needs to be a shared vision around these ideas and a common desire to work more effectively, which in the past has been constrained by existing systems and practices.

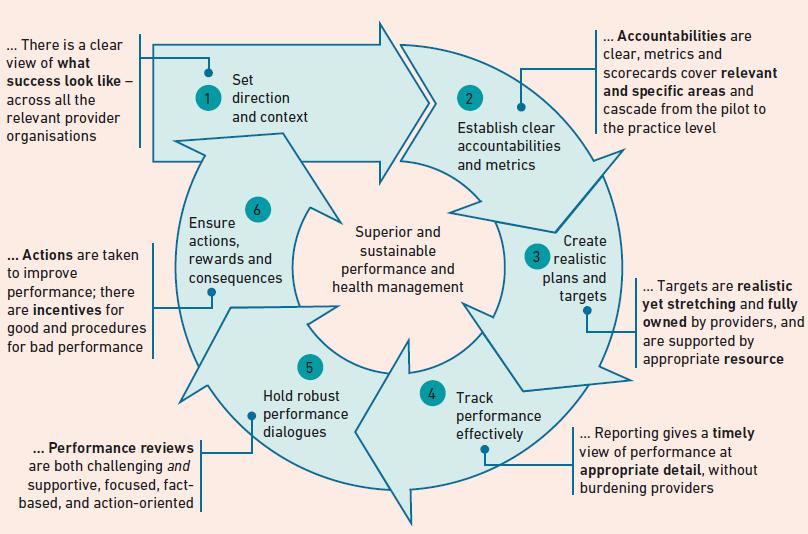

Transformation programme design principles The high-level design of a transformation programme is shown in Figure 7.8, beginning with ideas about what successful transformation comprises, defined in terms of purpose and objectives. It then moves on to accountabilities and metrics. In the context of integrated care, this would include definitions in all relevant areas, from region or city down to provider level including hospitals, primary care and local charities if involved. Realistic targets are set in collaboration and accepted throughout the health system, linked to reporting of performance that carefully balances the value and needs for reporting with the resources used in doing so. Performance review and problem solving, alongside incentives for superior reporting, complete the cycle.

Common reasons for failure in the design and implementation of integrated care are summarized at high level in Figure 7.9. Most importantly, having an overly ambitious target appears not to be the root cause of failure. In fact, failure is far more likely to derive from issues of engagement or limitations to the processes of engagement. Typically, these are seen

Questions

1. The case describes a major transformation of health care, away from separation of care into primary and hospital care and the functional organization of hospital care, toward a process focused on care delivered on ‘care pathways’. What kinds of shift of emphasis for staff and patients will it require?

2. Consider the enablers of change included. How might these enablers support change through ensuring effective connectivity, leverage and integration?

3. How important is effective change governance and why?

Step by Step Answer:

Organizational Change

ISBN: 9781292243436

6th Edition

Authors: Barbara Senior, Stephen Swailes, Colin Carnall