The history of Chinese trade is long and distinct, with the twentieth century being marked by large

Question:

The history of Chinese trade is long and distinct, with the twentieth century being marked by large shifts in policy. A focus on the history of trade between the USA and China helps to reveal some of the fundamental moments in the history of Chinese trade. In 1936, the USA accounted for 22 percent of China’s exports and 20 percent of its imports. In 1949, the Chinese Communist Party seized control of China and, after decades of struggle, founded the People’s Republic of China. Under this new regime, the economy was completely state controlled. These changes, the Korean War from 1950 to 1953, and the subsequent embargo toward China caused a sharp decline in USA–China trade relations. In 1972, the American share of China’s total trade accounted for only 1.6 percent.

In 1978, under the new leadership of Deng Xiaoping, China began the long process of economic reform. Initially focused on just agricultural reform, these economic reforms eventually became a transition to a capitalist and globally integrated economy. Focused on the four modernizations – the modernization of industry, agriculture, science and technology, and national defense – these reforms represented a deep-seated shift in policy and helped to spur a steady growth of USA–China trade. Between 1990 and 2000, total trade rose from \($20\) million to over \($116\) billion. By 2000, America had become China’s second-largest trade partner and China was the USA’s fourth-largest importer, supplying a wide variety of goods.

Moreover, investors poured money into China, with \($400\) billion invested in 2001, \($28.5\) billion of this coming from the USA alone. It is estimated that by 2010, China’s total imports will reach three trillion dollars, a large share of which will come from the USA.

For 13 years, China had applied for WTO membership, but this effort had not been successful, mainly due to US opposition. This opposition was based on a laundry list of economic and political issues, including concerns with human rights, tension between Taiwan and China, China’s nuclear arsenal, objections from labor unions in the USA, and the use of protectionist policies by China. “As bad as our trade deficit with China is today, it will grow even worse if we approve a permanent trade deal,” said House Minority Whip David Bonior (D., Mich.)

back in October 1999. Even with this opposition, on November 15, 1999, an historic agreement was reached between Chinese and American trade negotiators, which set the stage for China’s formal entry into the WTO.

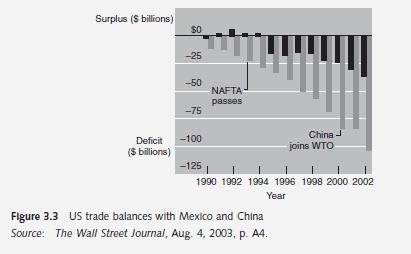

One of the major worries by those who opposed the normalization of trade relations with China was concern about a growing trade imbalance between the two countries. According to US trade data, the trade deficit with China was \($69\) billion in 1999, \($83\) billion in 2000, \($85\) billion in 2001, and \($103\) billion in 2002 (see figure 3.3). Many believed that this growing deficit was due to China’s high tariffs and numerous restrictions on American exports. In joining the WTO on December 11, 2001, China agreed to lower its average tariff from 16.7 percent in 2000 to 10 percent in 2005, and to reduce the number of items under import license and quota from approximately 300 to zero in the next 5 years. In addition, China agreed to liberalize foreign investment in banking, insurance, financial services, wholesale/retail trade, and telecommunications. All these industries had been under tight government control until recently.

In return, the USA granted China permanent normalized trade relations status. Without this legislation, China’s trade status would be open to yearly debate, as it had been in the past. Additionally, China, as a member of the WTO, now enjoys open markets with all other WTO members, including the USA. One area in which this has provided a great advantage for China’s exports is in its textile industry. Textiles have been one of the Chinese major export items but, for years, the USA had imposed a quota on them. With the removal of these tariffs, the Chinese textile industry has boomed and it grew by 27 percent in 2001.

Many US multinational companies are in the midst of an unprecedented wave of shifting capital and technology to plants in China and other low-cost locales. This wave pulls away vast chunks of business that formerly filtered down through the intricate networks of suppliers and producers inside the USA. While the tension is most acute in trade associations and other industry groups, it has recently gained political momentum that threatens to spill over into political debates. To be sure, there are some things that all manufacturers can rally around, such as the broad push to get China to stop pegging the value of the yuan to the dollar at what many believe is an artificially low level. Some economists believe that the Chinese currency is undervalued by as much as 40 percent, which gives Chinese goods a built-in advantage against identical US products. Even with the unanimity, the Bush Administration does not appear eager to get involved.

In dollar terms, China’s economy is about 10 percent of the US economy and 20 percent of Japan’s. After adjusting for differences in the cost of living (purchasing power parity), however, China’s economy is more than half as large as the US economy and surpassed Japan to become the world’s second-largest economy; in 2002, the gross domestic product was \($10.1\) trillion for the USA, \($6\) trillion for China, and \($3.6\) for Japan. It grew 7.3 percent in 2001 and an average of about 9 percent annually between 1980 and 2000. China expects its economy to grow at an annual rate of 6–7 percent over the next 10 years. China’s membership of the WTO represents another great step as it continues to move toward a more capitalistic economy. It will increase the opportunities for Chinese growth and will help China play an increasingly large role in the global economy. All of these trends together point to the emergence of China as a dominant, if not the dominant, economic power for the coming century.

China’s first manned space shot – the blastoff of a rivalry with the USA and Russia in civil space exploration and military innovation – happened in a flash but reflects the long, methodical effort of a serious program. The Shenzhou V spacecraft, launched on October 15, 2003, circled Earth 14 times before safely parachuting onto the grasslands of Inner Mongolia. The Shenzhou’s progress heightened already strong public enthusiasm for the 11-year-old manned program as a symbol of China’s rising economic and technical prowess.

Case Questions 1 What are some of the sources of trade friction between China and the USA? Why do some scholars view this friction as a positive sign?

2 What is managed trade and how does it apply to China and the USA?

3 Discuss what steps the USA can take to reduce its trade deficit with China. Mention the deflation of economies, devaluation of the currency, and the establishment of public control.

4 Suppose that the value of the US dollar sharply depreciates. Under these conditions, how would the J-curve discussed in this chapter apply to the trade relationship between China and the USA?

5 Discuss in broad terms the major changes since World War II in the trade relations between China and the USA in terms of actual balance of payments and foreign direct investment.

6 The website of the US Central Intelligence Agency, www.cia.gov, and the website of the US Census Bureau, www.census.gov, both contain economic data and statistics on trade.

Use specific numbers from these two sites to support some of your claims in the answer to question 5.

Step by Step Answer:

Global Corporate Finance Text And Cases

ISBN: 9781405119900

6th Edition

Authors: Suk H. Kim, Seung H. Kim