Thirty-five years ago, when an Indiana accounting professor, Dan Edwards, placed an order to buy shares of

Question:

Thirty-five years ago, when an Indiana accounting professor, Dan Edwards, placed an order to buy shares of Sony Corp., his broker tried to talk him out of it, saying “nobody has ever heard of that company.” Nevertheless, Professor Edwards persisted, and his broker made the purchase.

To begin with, it took 2 days for the order to go through; once it did, Professor Edwards couldn’t find price quotes without calling his broker. When annual reports came, they were in Japanese.

How times have changed. Thanks largely to the rise of American depository receipts (ADRs), these days US investors can trade many foreign shares, such as DaimlerChrysler, with no more difficulty than it takes to buy domestic shares. Created in 1927 by financier J. P. Morgan as a way of facilitating US investment abroad, an ADR is a negotiable certificate issued by a US bank in the USA to represent the underlying shares of foreign stock, which are held in a custodian bank. ADRs are sold, registered, and transferred in the USA in the same way as any share of domestic stock. Fueled by Americans’ interest in foreign markets, ADRs now account for more than 5 percent of all trading volume on the major US exchanges. Three of the 10 most active NYSE stocks in 1996 were ADRs – Telefonos de Mexico SA, Hanson PLC, and Glaxo Wellcome PLC. Currently, there are more than 1,400 ADRs in the USA. This figure represents a 50 percent increase from only 7 years ago. “The ADR market has grown like a jerry built house for the last few years,” says Eric Fry, President of Holl International, a San Francisco management firm. “It started at 2,500 square feet, and now it’s 14,000 square feet.”

In 1993, Daimler-Benz management decided to adjust its financial reporting in order to list shares of stock as ADRs on the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE). This decision resulted from months of negotiations between Daimler-Benz, the NYSE, and the SEC (Securities and Exchange Commission). In 1993, Daimler-Benz saw profits fall by 25 percent from the previous year, and prospects for the future were not bright. The company relied historically on strong profits for cash flow; therefore, its management realized that it would have to look to other sources of cash to fund future growth. One way to raise funds was to issue shares of stock in foreign stock exchanges such as the NYSE.

Daimler-Benz was Europe’s largest industrial company – best known for its vehicle division, Mercedes-Benz – but it consisted of 23 business units housed in five divisions: passenger cars, commercial vehicles, aerospace, services, and directly managed business. In November 1998, Daimler-Benz purchased Chrysler for \($40.5\) billion in its ADRs, which created the world’s second-largest company on the Fortune Global 500. This newly combined company, named DaimlerChrysler, became the fifth-largest automaker in the world ranked by production. The world’s top five automakers based on 1998 production of cars and light trucks are GM (7.8 million units), Ford (6.5 million units), Toyota (4 million units), Volkswagen (3.9 million units), and DaimlerChrysler (3.6 million units).

Unlike other mergers, the overall goal of this merger is just growth. DaimlerChrysler said that it would generate annual savings and revenue gains of at least \($3\) billion, with no plant closures or layoffs planned. The company’s top integration priorities included: (1) combining efforts to boost Chrysler and Daimler sales in Asia and Latin America; (2) building and selling an extra 30,000 units of the Mercedes M-class sport-utility vehicle around the world; (3) identifying ways to use Daimler diesel engines in Chrysler cars and trucks; (4) developing a Daimler-

Benz minivan, working with Chrysler’s minivan platform team; (5) eliminating overlapping research into fuel cells, electric cars, and advanced diesel engines; and (6) consolidating the functions of marketing and finance.

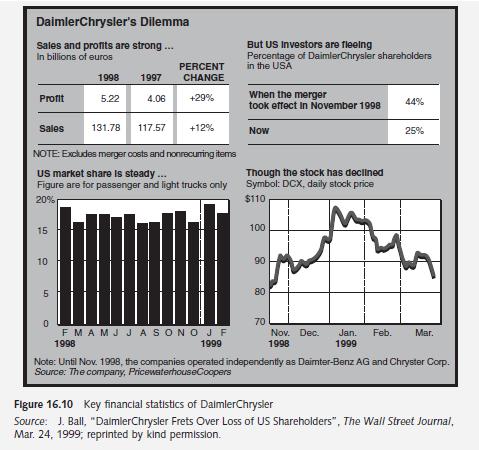

Figure 16.10 shows that this combined company posted substantial gains in both sales and profits in 1998 over 1997. Furthermore, DaimlerChrysler predicted a 4 percent growth in sales and operating profit in 1999. Analysts did not dispute the company’s forecast for even faster growth in sales and earnings beyond 1999. In just 4 months after the historic merger, however, the portion of US investors in DaimlerChrysler dropped from 44 percent in November 1998 to 25 percent in March 1999. In the meantime, the company’s share price fell 21 percent from a 52-week high of \($108.625\) on January 6, 1999, to \($86\) on March 23, 1999, in NYSE composite trading. These two pieces of bad news – the drop in US ownership and the decline in the share price – caused DaimlerChrysler in March 1999 to abruptly end its efforts to purchase Japan’s Nissan Motor Co. Apparently, the overall goal of DaimlerChrysler at the time of their merger – just growth –

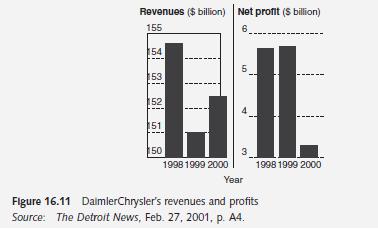

turned out to be an unrealizable dream. Figure 16.11 shows that the company’s revenues and profits fell sharply after their 1998 merger. Consequently, DaimlerChrysler announced its restructured plan for Chrysler Group in February 2001. Under this plan, the company would:

(1) cut 26,000 jobs, close six plants, and reduce car and truck output by 15 percent; (2) lower parts and materials costs by \($7.8\) billion through 2003; (3) cut manufacturing expenses by \($1.8\) billion and sell noncore assets; (4) lower the break-even point from 113 percent to 83 percent;

(5) reduce fixed costs by \($2.5\) billion by cutting workforce, trimming white-collar benefits, and noncore asset sales; (6) increase annual revenues by \($4.8\) billion by 2003; and (7) reduce engineering costs through a variety of actions. However, critics charge that DaimlerChrysler should have taken these actions when they merged in 1998. Some observers argue that all major merged companies restructure their business operations at the time of the merger by laying off thousands of workers, closing factories, firing long-time managers, and spinning off noncore businesses.

Case Questions 1 Describe American depository receipts in some detail.

2 Why did Daimler-Benz and other foreign companies decide to list their ADRs on the NYSE?

3 Briefly describe how to choose ADRs.

4 What is the downside of ADR investment?

5 Both sales and profits in DaimlerChrysler posted big gains in 1998 and expected to increase even faster beyond 1999. In the meantime, the company’s US ownership and share price declined sharply in the first 4 months after the merger. Explain this apparent conflict between the company’s profits and its share price.

6 To list their stocks in the New York Stock Exchange, foreign companies have to comply with the registration and disclosure requirements established by the US Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC). Use the website of the SEC, www.sec.gov/, to review disclosure requirements in SEC final rules related to foreign investment and trade.

Step by Step Answer:

Global Corporate Finance Text And Cases

ISBN: 9781405119900

6th Edition

Authors: Suk H. Kim, Seung H. Kim