In late 2005, Deloitte's Navistar audit for the fiscal year ending October 31, 2005, was nearing completion

Question:

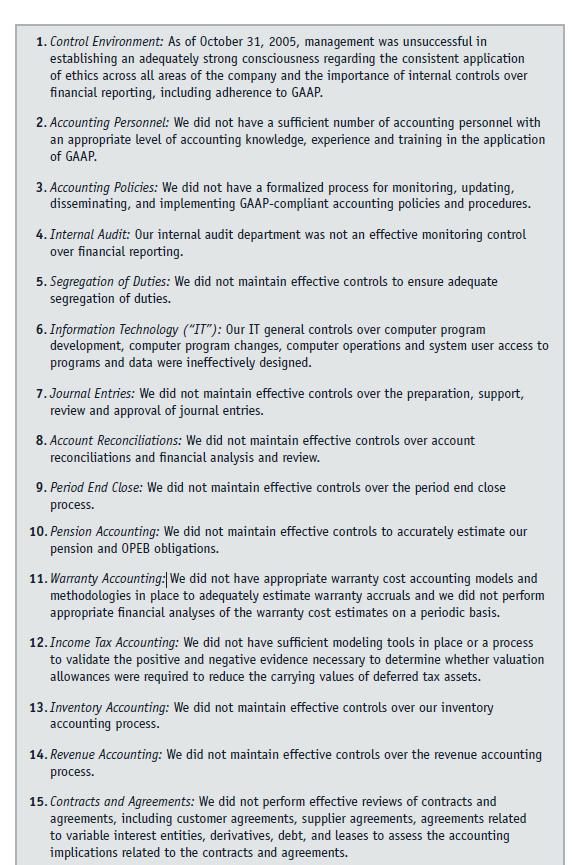

In late 2005, Deloitte's Navistar audit for the fiscal year ending October 31, 2005, was nearing completion when the audit engagement partner took a "mysterious medical leave"2 and was replaced. Navistar's new audit engagement partner was a former Arthur Andersen partner who had joined Deloitte after a felony conviction in 2002 drove Andersen out of business.3 The new engagement partner was apparently shocked at the condition of Navistar's accounting records and the work that had been done to that point on the 2005 audit. "The new lead engagement partner . . . began questioning almost everything that had been done or approved previously. . . [and] refused to accept any of the work . . . the [audit] team had already done and basically, according to Navistar, started the audit over." 4 Navistar's management team was less than happy with the sudden turn of events.The company's executives were even more dismayed when the delay in the 2005 audit prevented Navistar from meeting the filing deadline for its annual Form 10-K with the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC). In February 2006, Deloitte advised Navistar management that it could no longer rely on representations made by the company's controller, which caused Navistar o replace that individual.Deloitte also asked Navistar to reassign a top executive of its large finance subsidiary, Navistar Financial Corporation, which the company did. The tense relationship between Deloitte and Navistar ended in April 2006 when the company's audit committee dismissed Deloitte and retained KPMG as the company's independent auditor.Over the following 20 months, "Navistar spent more than $200 million to reconduct their 2002-2004 audits, redo and complete their 2005 audit, and reevaluate a neverending list of material weaknesses and significant deficiencies in internal controls over financial reporting."5 Navistar hired PricewaterhouseCoopers, Ernst & Young, and two large consulting firms to overhaul its accounting and financial reporting functions. In the meantime, the New York Stock Exchange delisted Navistar's common stock, which complicated the company's efforts to raise needed capital. In late 2007, Navistar finally filed its 2005 Form 10-K and restated financial statements for fiscal 2003, fiscal 2004, and the first three quarters of 2005 with the SEC. The restatements reduced Navistar's previously reported profits by nearly $680 million. Navistar's 2005 Form 10-K reported 15 material weaknesses in the company's internal controls over financial reporting. Exhibit 1 provides brief summaries of those material weaknesses that were excerpted from that Form 10-K.

Questions1. Identify the advantages and disadvantages of mandatory audit firm rotation. What, if any, auditor rotation rules are in effect in the United States?2. What is the formal definition of a “material weakness” in internal control? How do material weaknesses in internal control differ from “significant deficiencies” in internal control? Identify the three material weaknesses in Exhibit 1 that you believe were most critical. Defend your choices. Can an organization’s internal controls be so inadequate that it is not possible for the entity to be audited? Defend your answer.3. Is it appropriate for an audit firm “to function as a de facto adjunct” to a client’s accounting department? Why or why not? Which party or parties were primarily responsible for Deloitte being dismissed as Navistar’s independent auditor in April 2006? Defend your answer.4. Define what is meant by the phrase “planning materiality threshold”? What factors should be considered in establishing such thresholds? Are there any conditions under which it is appropriate for auditors to change a planning materiality threshold after the given audit has begun?5. This case includes the following quote from a former PCAOB official: “The [audit] firm tends to be the subject of disciplinary action when there is a failure of oversight or supervision. Where a particular partner simply makes an error but the firm was not negligent, only the party may get named in the proceeding.” Do you believe that Deloitte, in addition to Linden and Anderson, should have been sanctioned by the PCAOB in connection with the 2003 Navistar audit? Justify your answer.6. What professional standards require accounting firms to develop quality controls for their audit practices? What key issues should such quality controls address? In commenting on Deloitte’s quality controls, the PCAOB referred to the “culture” of that firm. What are the key factors or conditions that influence the “culture” within an accounting firm’s audit practice?7. Do you believe that the PCAOB overstepped its regulatory role and responsibilities by beginning a dialogue regarding the possible need for mandatory audit firm rotation? Why or why not? Do you agree with U.S. Representative Garrett that the PCAOB is not a policy-making body? Explain.8. Deloitte maintained that it was not appropriate for PCAOB inspection teams to “second-guess” the “reasonable judgments” of skilled professionals. Do you agree? Defend your answer.

Step by Step Answer: