In the early 1930s, the Great Depression forced engineering student William Harrah to drop out of UCLA.

Question:

In the early 1930s, the Great Depression forced engineering student William Harrah to drop out of UCLA. Known as a "hustler" by his friends, Harrah began operating a bingo parlor to support himself. After repeated confrontations with law enforcement authorities that centered on the legality of his bingo games, Harrah moved his business operations to Nevada, which had less restrictive gambling laws than California.

Over the next several decades, the resourceful and enigmatic entrepreneur assembled an impressive collection of gaming properties.1 Harrah eventually took his company public in 1971 to raise the funds he needed to build the crown jewel of his business empire, the five-star hotel and gaming resort Harrah's Lake Tahoe.

In 1973, William Harrah registered Harrah's Inc. with the New York Stock Exchange, making it the first gaming company listed on the Big Board. In 2005, long after its founder's death, the renamed Harrah's Entertainment Inc., became the nation's largest gaming company when it acquired the opulent Caesars Palace in Las Vegas and dozens of other major gaming properties operated by one of its primary competitors. The company's executives eventually renamed the firm Caesars Entertainment Corporation and listed its common stock on the NASDAQ under the ticker symbol CZR.

Over the years, Caesars and its predecessors have had more than their fair share of run-ins with regulatory authorities due to the company's aggressive business practices.

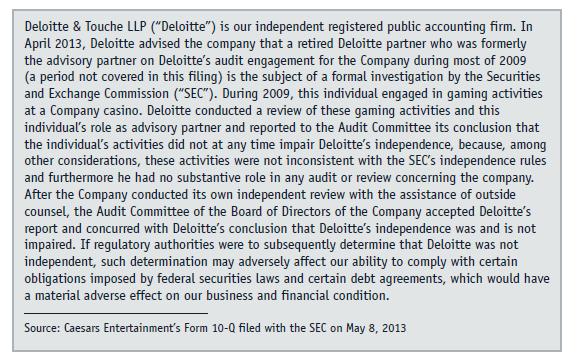

In early 2013, the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) launched an investigation involving Caesars. Ironically, the investigation was not prompted by any actions or decisions by the company's executives but rather by the conduct of James T. Adams, a former partner of the company's audit firm, Deloitte & Touche (Deloitte).2 Adams had served as the advisory partner on Deloitte's 2008 and 2009 audits of Caesars. During 2009, Adams had allegedly engaged in certain "gaming activities" at a Caesars casino that made the SEC question Deloitte's independence during the 2009 audit. Exhibit 1 presents the one-paragraph disclosure made by Caesars of the SEC investigation while it was in progress.

As noted in Exhibit 1, Caesars and Deloitte performed their own independent investigations and concluded that Adams' actions had not impaired Deloitte's independence. Also, notice Caesars reported that if a contrary conclusion was ultimately reached by the SEC, there could be “material adverse” consequences for the company.

Questions

1. Do you agree with Deloitte’s assertion that Adams had no “substantive role” in the 2008 and 2009 Caesars audits? Defend your answer.

2. The SEC applies a principles-based approach to mitigating the risks that may undercut auditor independence. Identify the four guiding principles applied by the SEC to protect the independence of auditors of public companies.

3. Assume Adams had used his personal funds to finance his gaming activities in the Caesars casino. Under those circumstances, would he have violated any ethical or professional standards? Again, defend your answer.

4. The SEC observed in AAER No. 3554 that “any loan . . . to or from an audit client” is “inconsistent” with auditor independence. Despite that statement, are there any circumstances in which an auditor can have an outstanding loan from an audit client? Explain.

Step by Step Answer: