1)

- Calculate the Balance Sheet effect of taking advantage of the supplier discount offered. (2% discount offered if paid within 10 days, and due within 30 days)

- Calculate the Income Statement effect of taking advantage of the supplier discount offered.

- Calculate the effective interest rate the company is paying if it is not taking the supplier discount.

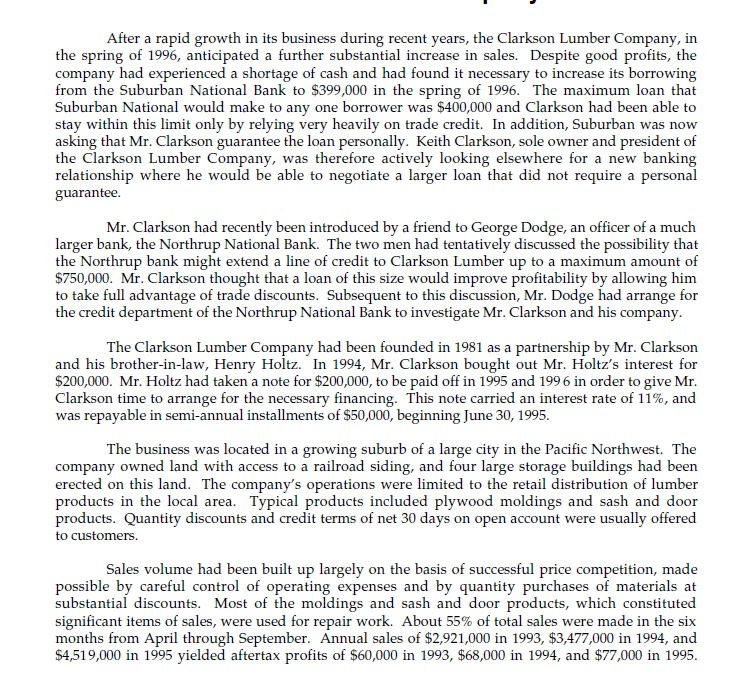

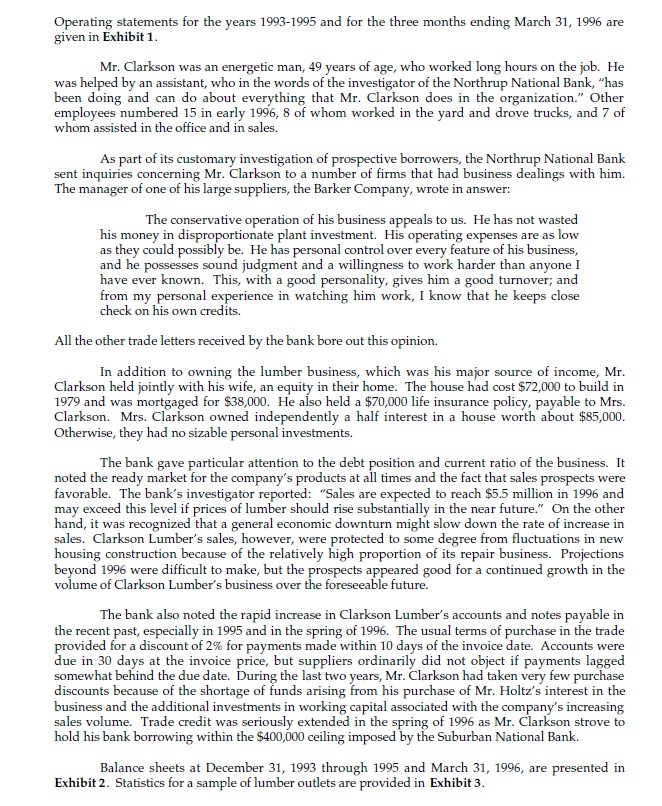

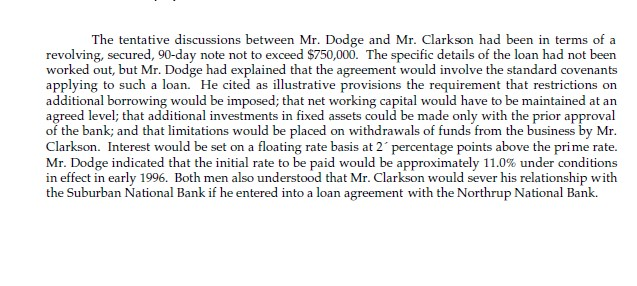

After a rapid growth in its business during recent years, the Clarkson Lumber Company, in the spring of 1996, anticipated a further substantial increase in sales. Despite good profits, the company had experienced a shortage of cash and had found it necessary to increase its borrowing from the Suburban National Bank to $399,000 in the spring of 1996. The maximum loan that Suburban National would make to any one borrower was $400,000 and Clarkson had been able to stay within this limit only by relying very heavily on trade credit. In addition, Suburban was now asking that Mr. Clarkson guarantee the loan personally. Keith Clarkson, sole owner and president of the Clarkson Lumber Company, was therefore actively looking elsewhere for a new banking relationship where he would be able to negotiate a larger loan that did not require a personal guarantee. Mr. Clarkson had recently been introduced by a friend to George Dodge, an officer of a much larger bank, the Northrup National Bank. The two men had tentatively discussed the possibility that the Northrup bank might extend a line of credit to Clarkson Lumber up to a maximum amount of $750,000. Mr. Clarkson thought that a loan of this size would improve profitability by allowing him to take full advantage of trade discounts. Subsequent to this discussion, Mr. Dodge had arrange for the credit department of the Northrup National Bank to investigate Mr. Clarkson and his company. The Clarkson Lumber Company had been founded in 1981 as a partnership by Mr. Clarkson and his brother-in-law, Henry Holtz. In 1994, Mr. Clarkson bought out Mr. Holtz's interest for $200,000. Mr. Holtz had taken a note for $200,000, to be paid off in 1995 and 1996 in order to give Mr. Clarkson time to arrange for the necessary financing. This note carried an interest rate of 11%, and was repayable in semi-annual installments of $50,000, beginning June 30, 1995. The business was located in a growing suburb of a large city in the Pacific Northwest. The company owned land with access to a railroad siding, and four large storage buildings had been erected on this land. The company's operations were limited to the retail distribution of lumber products in the local area. Typical products included plywood moldings and sash and door products. Quantity discounts and credit terms of net 30 days on open account were usually offered to customers. Sales volume had been built up largely on the basis of successful price competition, made possible by careful control of operating expenses and by quantity purchases of materials at substantial discounts. Most of the moldings and sash and door products, which constituted significant items of sales, were used for repair work. About 55% of total sales were made in the six months from April through September. Annual sales of $2,921,000 in 1993, $3,477,000 in 1994, and $4,519,000 in 1995 yielded aftertax profits of $60,000 in 1993, $68,000 in 1994, and $77,000 in 1995. Operating statements for the years 1993-1995 and for the three months ending March 31, 1996 are given in Exhibit 1. Mr. Clarkson was an energetic man, 49 years of age, who worked long hours on the job. He was helped by an assistant, who in the words of the investigator of the Northrup National Bank, "has been doing and can do about everything that Mr. Clarkson does in the organization." Other employees numbered 15 in early 1996, 8 of whom worked in the yard and drove trucks, and 7 of whom assisted in the office and in sales. As part of its customary investigation of prospective borrowers, the Northrup National Bank sent inquiries concerning Mr. Clarkson to a number of firms that had business dealings with him. The manager of one of his large suppliers, the Barker Company, wrote in answer: The conservative operation of his business appeals to us. He has not wasted his money in disproportionate plant investment. His operating expenses are as low as they could possibly be. He has personal control over every feature of his business, and he possesses sound judgment and a willingness to work harder than anyone I have ever known. This, with a good personality, gives him a good turnover; and from my personal experience in watching him work, I know that he keeps close check on his own credits. All the other trade letters received by the bank bore out this opinion. In addition to owning the lumber business, which was his major source of income, Mr. Clarkson held jointly with his wife, an equity in their home. The house had cost $72,000 to build in 1979 and was mortgaged for $38,000. He also held a $70,000 life insurance policy, payable to Mrs. Clarkson. Mrs. Clarkson owned independently a half interest in a house worth about $85,000. Otherwise, they had no sizable personal investments. The bank gave particular attention to the debt position and current ratio of the business. It noted the ready market for the company's products at all times and the fact that sales prospects were favorable. The bank's investigator reported: "Sales are expected to reach $5.5 million in 1996 and may exceed this level if prices of lumber should rise substantially in the near future." On the other hand, it was recognized that a general economic downturn might slow down the rate of increase in sales. Clarkson Lumber's sales, however, were protected to some degree from fluctuations in new housing construction because of the relatively high proportion of its repair business. Projections beyond 1996 were difficult to make, but the prospects appeared good for a continued growth in the volume of Clarkson Lumber's business over the foreseeable future. The bank also noted the rapid increase in Clarkson Lumber's accounts and notes payable in the recent past, especially in 1995 and in the spring of 1996. The usual terms of purchase in the trade provided for a discount of 2% for payments made within 10 days of the invoice date. Accounts were due in 30 days at the invoice price, but suppliers ordinarily did not object if payments lagged somewhat behind the due date. During the last two years, Mr. Clarkson had taken very few purchase discounts because of the shortage of funds arising from his purchase of Mr. Holtz's interest in the business and the additional investments in working capital associated with the company's increasing sales volume. Trade credit was seriously extended in the spring of 1996 as Mr. Clarkson strove to hold his bank borrowing within the $400,000 ceiling imposed by the Suburban National Bank. Balance sheets at December 31, 1993 through 1995 and March 31, 1996, are presented in Exhibit 2. Statistics for a sample of lumber outlets are provided in Exhibit 3. The tentative discussions between Mr. Dodge and Mr. Clarkson had been in terms of a revolving, secured, 90-day note not to exceed $750,000. The specific details of the loan had not been worked out, but Mr. Dodge had explained that the agreement would involve the standard covenants applying to such a loan. He cited as illustrative provisions the requirement that restrictions on additional borrowing would be imposed; that net working capital would have to be maintained at an agreed level; that additional investments in fixed assets could be made only with the prior approval of the bank, and that limitations would be placed on withdrawals of funds from the business by Mr. Clarkson. Interest would be set on a floating rate basis at 2 percentage points above the prime rate. Mr. Dodge indicated that the initial rate to be paid would be approximately 11.0% under conditions in effect in early 1996. Both men also understood that Mr. Clarkson would sever his relationship with the Suburban National Bank if he entered into a loan agreement with the Northrup National Bank. Exhibit 1 Operating Expenses for Years Ending December 31, 1993-1995, and for First Quarter 1996 (thousands of dollars) 1st Quarter 1996 1993 1994 1995 $2,921 $3,477 $4,519 $1,062 Net sales Cost of Goods Sold: Beginning inventory Purchases 330 2,209 $2,539 337 $2,202 337 2,729 $3,066 432 $2,634 432 3,579 $4,011 587 $3,424 587 819 $1,406 607 $799 Ending inventory Total Cost of Goods Sold Gross profit Operating expenses Earnings before interest and taxes Interest expense Net income before income taxes Provision for income taxes Net income 719 622 $97 23 $74 14 $60 843 717 $126 42 $84 16 $68 1,095 940 $155 56 $99 22 $77 263 244 $19 13 $6 1 $5 &in the first quarter of 1995, sales were $903,000 and net income was $7,000 Operating expenses include a cash salary for Mr. Clarkson of $75,000 in 1993; $80,000 in 1994; $85,000 in 1995; and $22,500 in the first quarter of 1996. Clarkson Lumber was required to estimate its income tax liability for the current tax year and pay four quarterly estimated tax installments during that year. The first $50,000 of pretax profits were taxed at a 15% rate; the next $25,000 were taxed at a 25% rate; the next $25,000 were taxed at a 34% rate; and profits in excess of $100,000 but less than $335,000 were taxed at a 39% rate. Exhibit 2 Balance Sheets at December 31, 1993-1995, and March 31, 1996 (thousands of dollars) 1st Quarter 1996 1993 1994 1995 Cash Accounts receivable, net Inventory Current assets Property, net Total Assets $ 43 306 337 $686 233 $919 $ 52 411 432 $ 895 262 $1,157 $ 56 606 587 $1,249 388 $1,637 $ 53 583 607 $1,243 384 $1,627 $ $ 60 100 213 42 Notes payable, banka Note payable to Holtz, current portion Notes payable, trade Accounts payable Accrued expenses Term loan, current portion Current liabilities Term loan Note payable, Mr. Holtz Total Liabilities Net worth Total Liabilities and Net Worth 20 $275 140 340 45 20 $ 565 120 100 $ 785 372 $ 390 100 127 376 75 20 $1,088 100 0 $1,188 449 $ 399 100 123 364 67 20 $1,073 100 0 $1,173 454 $415 504 $919 $1,157 $1,637 $1,627 a Interest is computed on the average outstanding loan balance at the rate of prime plus 2%. Interest is fixed at 11% times the outstanding balance. interest is fixed at 10.0% times the outstanding balance; the term loan is secured by the fixed assets and is repayable in semiannual installments of $10,000. After a rapid growth in its business during recent years, the Clarkson Lumber Company, in the spring of 1996, anticipated a further substantial increase in sales. Despite good profits, the company had experienced a shortage of cash and had found it necessary to increase its borrowing from the Suburban National Bank to $399,000 in the spring of 1996. The maximum loan that Suburban National would make to any one borrower was $400,000 and Clarkson had been able to stay within this limit only by relying very heavily on trade credit. In addition, Suburban was now asking that Mr. Clarkson guarantee the loan personally. Keith Clarkson, sole owner and president of the Clarkson Lumber Company, was therefore actively looking elsewhere for a new banking relationship where he would be able to negotiate a larger loan that did not require a personal guarantee. Mr. Clarkson had recently been introduced by a friend to George Dodge, an officer of a much larger bank, the Northrup National Bank. The two men had tentatively discussed the possibility that the Northrup bank might extend a line of credit to Clarkson Lumber up to a maximum amount of $750,000. Mr. Clarkson thought that a loan of this size would improve profitability by allowing him to take full advantage of trade discounts. Subsequent to this discussion, Mr. Dodge had arrange for the credit department of the Northrup National Bank to investigate Mr. Clarkson and his company. The Clarkson Lumber Company had been founded in 1981 as a partnership by Mr. Clarkson and his brother-in-law, Henry Holtz. In 1994, Mr. Clarkson bought out Mr. Holtz's interest for $200,000. Mr. Holtz had taken a note for $200,000, to be paid off in 1995 and 1996 in order to give Mr. Clarkson time to arrange for the necessary financing. This note carried an interest rate of 11%, and was repayable in semi-annual installments of $50,000, beginning June 30, 1995. The business was located in a growing suburb of a large city in the Pacific Northwest. The company owned land with access to a railroad siding, and four large storage buildings had been erected on this land. The company's operations were limited to the retail distribution of lumber products in the local area. Typical products included plywood moldings and sash and door products. Quantity discounts and credit terms of net 30 days on open account were usually offered to customers. Sales volume had been built up largely on the basis of successful price competition, made possible by careful control of operating expenses and by quantity purchases of materials at substantial discounts. Most of the moldings and sash and door products, which constituted significant items of sales, were used for repair work. About 55% of total sales were made in the six months from April through September. Annual sales of $2,921,000 in 1993, $3,477,000 in 1994, and $4,519,000 in 1995 yielded aftertax profits of $60,000 in 1993, $68,000 in 1994, and $77,000 in 1995. Operating statements for the years 1993-1995 and for the three months ending March 31, 1996 are given in Exhibit 1. Mr. Clarkson was an energetic man, 49 years of age, who worked long hours on the job. He was helped by an assistant, who in the words of the investigator of the Northrup National Bank, "has been doing and can do about everything that Mr. Clarkson does in the organization." Other employees numbered 15 in early 1996, 8 of whom worked in the yard and drove trucks, and 7 of whom assisted in the office and in sales. As part of its customary investigation of prospective borrowers, the Northrup National Bank sent inquiries concerning Mr. Clarkson to a number of firms that had business dealings with him. The manager of one of his large suppliers, the Barker Company, wrote in answer: The conservative operation of his business appeals to us. He has not wasted his money in disproportionate plant investment. His operating expenses are as low as they could possibly be. He has personal control over every feature of his business, and he possesses sound judgment and a willingness to work harder than anyone I have ever known. This, with a good personality, gives him a good turnover; and from my personal experience in watching him work, I know that he keeps close check on his own credits. All the other trade letters received by the bank bore out this opinion. In addition to owning the lumber business, which was his major source of income, Mr. Clarkson held jointly with his wife, an equity in their home. The house had cost $72,000 to build in 1979 and was mortgaged for $38,000. He also held a $70,000 life insurance policy, payable to Mrs. Clarkson. Mrs. Clarkson owned independently a half interest in a house worth about $85,000. Otherwise, they had no sizable personal investments. The bank gave particular attention to the debt position and current ratio of the business. It noted the ready market for the company's products at all times and the fact that sales prospects were favorable. The bank's investigator reported: "Sales are expected to reach $5.5 million in 1996 and may exceed this level if prices of lumber should rise substantially in the near future." On the other hand, it was recognized that a general economic downturn might slow down the rate of increase in sales. Clarkson Lumber's sales, however, were protected to some degree from fluctuations in new housing construction because of the relatively high proportion of its repair business. Projections beyond 1996 were difficult to make, but the prospects appeared good for a continued growth in the volume of Clarkson Lumber's business over the foreseeable future. The bank also noted the rapid increase in Clarkson Lumber's accounts and notes payable in the recent past, especially in 1995 and in the spring of 1996. The usual terms of purchase in the trade provided for a discount of 2% for payments made within 10 days of the invoice date. Accounts were due in 30 days at the invoice price, but suppliers ordinarily did not object if payments lagged somewhat behind the due date. During the last two years, Mr. Clarkson had taken very few purchase discounts because of the shortage of funds arising from his purchase of Mr. Holtz's interest in the business and the additional investments in working capital associated with the company's increasing sales volume. Trade credit was seriously extended in the spring of 1996 as Mr. Clarkson strove to hold his bank borrowing within the $400,000 ceiling imposed by the Suburban National Bank. Balance sheets at December 31, 1993 through 1995 and March 31, 1996, are presented in Exhibit 2. Statistics for a sample of lumber outlets are provided in Exhibit 3. The tentative discussions between Mr. Dodge and Mr. Clarkson had been in terms of a revolving, secured, 90-day note not to exceed $750,000. The specific details of the loan had not been worked out, but Mr. Dodge had explained that the agreement would involve the standard covenants applying to such a loan. He cited as illustrative provisions the requirement that restrictions on additional borrowing would be imposed; that net working capital would have to be maintained at an agreed level; that additional investments in fixed assets could be made only with the prior approval of the bank, and that limitations would be placed on withdrawals of funds from the business by Mr. Clarkson. Interest would be set on a floating rate basis at 2 percentage points above the prime rate. Mr. Dodge indicated that the initial rate to be paid would be approximately 11.0% under conditions in effect in early 1996. Both men also understood that Mr. Clarkson would sever his relationship with the Suburban National Bank if he entered into a loan agreement with the Northrup National Bank. Exhibit 1 Operating Expenses for Years Ending December 31, 1993-1995, and for First Quarter 1996 (thousands of dollars) 1st Quarter 1996 1993 1994 1995 $2,921 $3,477 $4,519 $1,062 Net sales Cost of Goods Sold: Beginning inventory Purchases 330 2,209 $2,539 337 $2,202 337 2,729 $3,066 432 $2,634 432 3,579 $4,011 587 $3,424 587 819 $1,406 607 $799 Ending inventory Total Cost of Goods Sold Gross profit Operating expenses Earnings before interest and taxes Interest expense Net income before income taxes Provision for income taxes Net income 719 622 $97 23 $74 14 $60 843 717 $126 42 $84 16 $68 1,095 940 $155 56 $99 22 $77 263 244 $19 13 $6 1 $5 &in the first quarter of 1995, sales were $903,000 and net income was $7,000 Operating expenses include a cash salary for Mr. Clarkson of $75,000 in 1993; $80,000 in 1994; $85,000 in 1995; and $22,500 in the first quarter of 1996. Clarkson Lumber was required to estimate its income tax liability for the current tax year and pay four quarterly estimated tax installments during that year. The first $50,000 of pretax profits were taxed at a 15% rate; the next $25,000 were taxed at a 25% rate; the next $25,000 were taxed at a 34% rate; and profits in excess of $100,000 but less than $335,000 were taxed at a 39% rate. Exhibit 2 Balance Sheets at December 31, 1993-1995, and March 31, 1996 (thousands of dollars) 1st Quarter 1996 1993 1994 1995 Cash Accounts receivable, net Inventory Current assets Property, net Total Assets $ 43 306 337 $686 233 $919 $ 52 411 432 $ 895 262 $1,157 $ 56 606 587 $1,249 388 $1,637 $ 53 583 607 $1,243 384 $1,627 $ $ 60 100 213 42 Notes payable, banka Note payable to Holtz, current portion Notes payable, trade Accounts payable Accrued expenses Term loan, current portion Current liabilities Term loan Note payable, Mr. Holtz Total Liabilities Net worth Total Liabilities and Net Worth 20 $275 140 340 45 20 $ 565 120 100 $ 785 372 $ 390 100 127 376 75 20 $1,088 100 0 $1,188 449 $ 399 100 123 364 67 20 $1,073 100 0 $1,173 454 $415 504 $919 $1,157 $1,637 $1,627 a Interest is computed on the average outstanding loan balance at the rate of prime plus 2%. Interest is fixed at 11% times the outstanding balance. interest is fixed at 10.0% times the outstanding balance; the term loan is secured by the fixed assets and is repayable in semiannual installments of $10,000