Answered step by step

Verified Expert Solution

Question

1 Approved Answer

1. Determine the initial cash needs to start the business. 2. Once uMunch starts operating, determine the expenses that will be fixed costs and variable

1. Determine the initial cash needs to start the business.

2. Once uMunch starts operating, determine the expenses that will be fixed costs and

variable costs.

3. Project uMunchs sales on a monthly basis for 2019, 2020 and 2021.

4. Prepare a monthly cash budget for 2019, 2020, and 2021. Hint: If uMunch ends any

month with a negative cash balance, then use the line of credit and factor in the

resulting interest expense.

5. Prepare 2019, 2020, and 2021, Income statements and balance sheets.

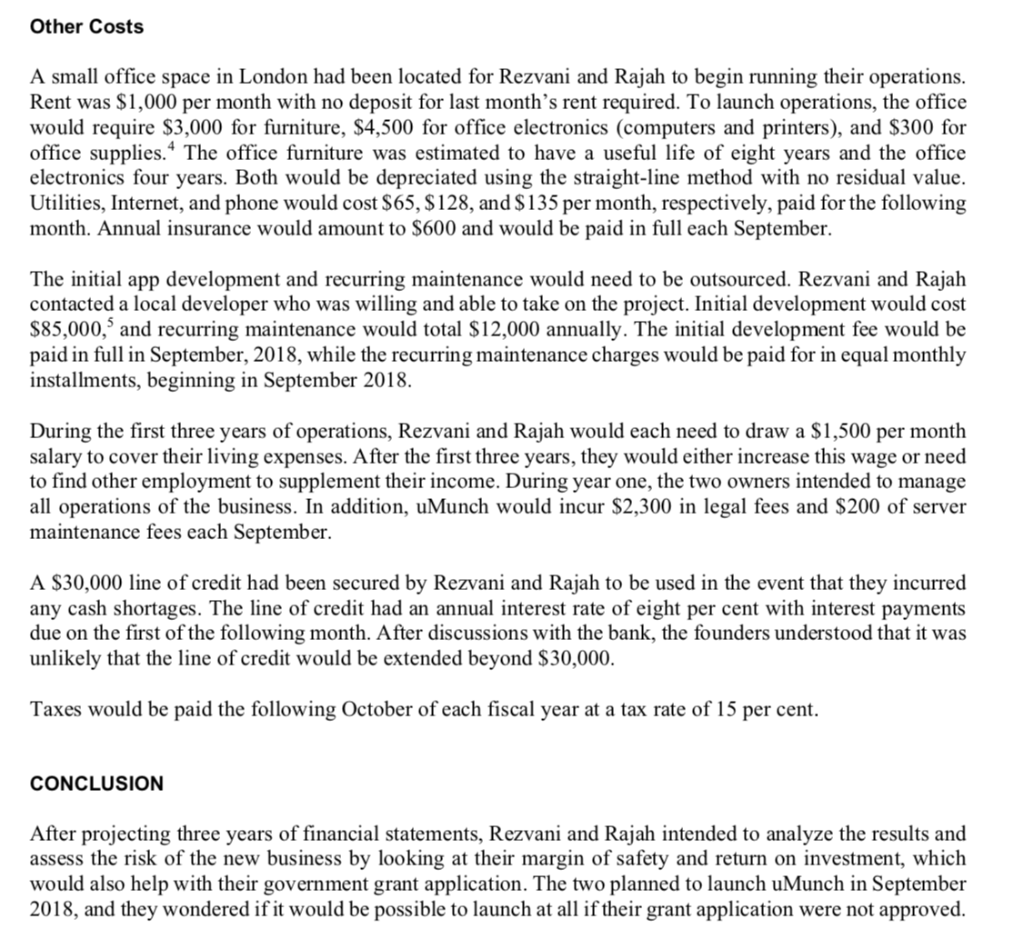

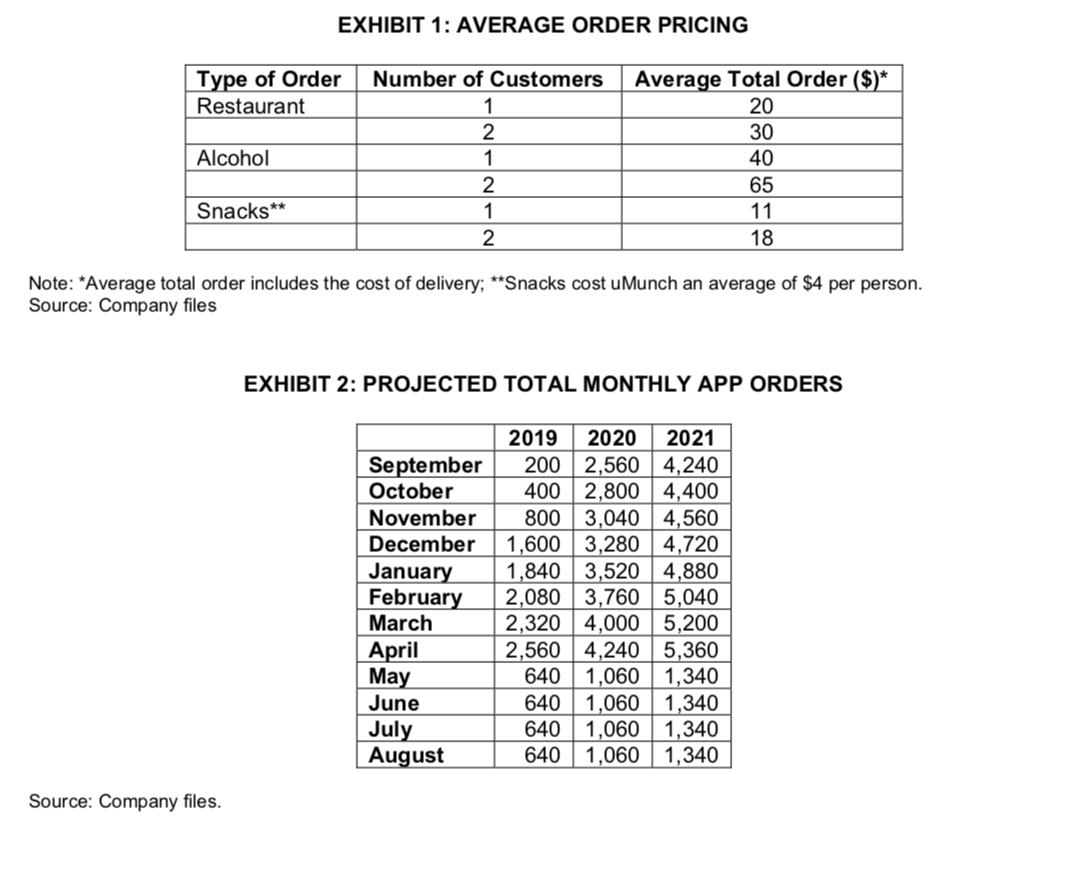

locally owned, student-oriented restaurants first, believing that these restaurants were more likely than chain restaurants to try something new. PROJECTIONS Sales After surveying the student body, Rezvani and Rajah determined early on that it was most likely that students would order either by themselves or with only one other individual. Of the total projected orders, it was estimated that 50 per cent would be attributed to restaurant sales, 10 per cent to alcohol, and 40 per cent to snacks. In each of these categories, half of the orders would be for one person and the other half would be for two (see Exhibit 1). Due to the re-order nature of the app and the expectations for growth, the pair understood that during the first three years of operations, sales would likely vary considerably from month to month. After speaking with several small-business owners in the area regarding their early sales and researching the experiences of other app-based delivery services, they concluded that they would likely experience more growth during the months when students were in school compared to the summer months (see Exhibit 2). All transactions were paid by credit card. In order to process these transactions, uMunch contracted Stripe, a third-party credit card processing company. All consumer payments would be managed by Stripe, which would then deposit the funds directly to uMunch on a semi-monthly basis. All restaurants featured on the app would be paid directly by Stripe on the same day as u Munch. Stripe charged 30 cents per credit card used in each transaction plus 2.9 per cent of every sale. All transaction fees would be covered by Munch in full. The app's semi-monthly inflows would be net of these transaction fees. To complete these deliveries, another third-party company, Debb Delivery (Debb), would be contracted. In order to allow for the legal delivery of alcohol, Debb's drivers would be Smart Serve Certified. When a delivery driver picked up a restaurant order, the driver would be paid immediately for the delivery charge by the restaurant Restaurant delivery fees of $6 were included in the total transaction paid by the customer. The delivery fee and 75 per cent of the food order would be paid directly to the restaurant through Stripe. When the delivery driver delivered an alcohol or snack order, the driver would first need to travel to the LCBO or partner convenience store and purchase the item(s) with his own money. Since the delivery driver would not have to wait for food to be prepared in these instances, the delivery fee was lower, at $5 per delivery. Both the delivery fee and the cost of the alcohol and/or snacks would be paid to Debb on the first of the following month. Debb would then distribute the funds accordingly to the delivery drivers. Advertising Marketing would play a critical role in the growth of Munch. Over the course of the first three years of operations, the founders intended to advertise using Facebook and Instagram, and by distributing information about the app on postcards through a direct-mail campaign. In year one, $3,000 was budgeted toward marketing. Of the total advertising budget, Facebook and Instagram would represent 90 per cent, and postcards would represent the remaining 10 per cent. In years two and three, the budget would increase to $6,000 and $9,000, respectively. Advertising expenses were expected to be incurred evenly between the months of August and March each year, and would be paid in the same month. Other Costs A small office space in London had been located for Rezvani and Rajah to begin running their operations. Rent was $1,000 per month with no deposit for last month's rent required. To launch operations, the office would require $3,000 for furniture, $4,500 for office electronics (computers and printers), and $300 for office supplies.* The office furniture was estimated to have a useful life of eight years and the office electronics four years. Both would be depreciated using the straight-line method with no residual value. Utilities, Internet, and phone would cost $65, $128, and $135 per month, respectively, paid for the following month. Annual insurance would amount to $600 and would be paid in full each September. The initial app development and recurring maintenance would need to be outsourced. Rezvani and Rajah contacted a local developer who was willing and able to take on the project. Initial development would cost $85,000, and recurring maintenance would total $12,000 annually. The initial development fee would be paid in full in September, 2018, while the recurring maintenance charges would be paid for in equal monthly installments, beginning in September 2018. During the first three years of operations, Rezvani and Rajah would each need to draw a $1,500 per month salary to cover their living expenses. After the first three years, they would either increase this wage or need to find other employment to supplement their income. During year one, the two owners intended to manage all operations of the business. In addition, uMunch would incur $2,300 in legal fees and $200 of server maintenance fees each September. A $30,000 line of credit had been secured by Rezvani and Rajah to be used in the event that they incurred any cash shortages. The line of credit had an annual interest rate of eight per cent with interest payments due on the first of the following month. After discussions with the bank, the founders understood that it was unlikely that the line of credit would be extended beyond $30,000. Taxes would be paid the following October of each fiscal year at a tax rate of 15 per cent. CONCLUSION After projecting three years of financial statements, Rezvani and Rajah intended to analyze the results and assess the risk of the new business by looking at their margin of safety and return on investment, which would also help with their government grant application. The two planned to launch uMunch in September 2018, and they wondered if it would be possible to launch at all if their grant application were not approved. EXHIBIT 1: AVERAGE ORDER PRICING | Type of Order Restaurant Number of Customers | Average Total Order ($)* 1 20 30 1 L 40 Alcohol 2 65 Snacks** 1 2 11 18 Note: *Average total order includes the cost of delivery; **Snacks cost u Munch an average of $4 per person. Source: Company files EXHIBIT 2: PROJECTED TOTAL MONTHLY APP ORDERS September October November December January February March April May June July August 2019 200 400 800 1,600 1,840 2,080 2,320 2,560 640 640 640 640 2020 2,560 2,800 3,040 3,280 3,520 3,760 4,000 4,240 1,060 1,060 1.060 1.060 2021 4,240 4,400 4,560 4,720 4,880 5,040 5,200 5,360 1,340 1,340 1.340 1,340 Source: Company files. in, they could add the items to their mobile shopping cart, and then share the cart with friends. The friends would then add their meals to the same cart and the app would automatically split the delivery cost among the members of the cart. All cart-sharers would be required to order from the same restaurant in order for there to be only one delivery charge. Because of the strict regulations on alcohol sales in Ontario, alcohol delivery did not earn Munch a profit. Rather, alcohol delivery was a service that Rezvani and Rajah considered would entice students to download the app. They hoped that these students would use and recommend the app to friends in the future. Alcohol was sold on the app for the same amount individuals could purchase it for at the LCBO, plus a delivery fee that would be remitted entirely to the delivery drivers by Munch. The app would be available to download free of charge from the Apple App Store. After the app gained popularity and the founders raised additional funds, they planned to create an Android version of the app to be released on the Google Play Store. CONSUMERS The app had to have a high number of daily users and offer a wide variety of restaurants, snack, and alcohol options. Without each other, neither restaurants nor students would be interested in using the app. It was therefore important that the two founders kept both consumer groups' wants and needs in mind when launching the app. Students Rezvani and Rajah anticipated that students would make up the bulk of their end consumers, given that these individuals were the most likely to eat regularly with people outside of their immediate family. The cart-sharing feature to split delivery costs would not be as desirable to families or couples given that they would more than likely be paying on one bill anyway. Within London, Ontario, there were over 50,000 students who attended Western University and Fanshawe College. The pair planned to target all advertisements at these individuals and host as many on-campus events as possible to get the word out. They anticipated that more student downloads would likely translate into more local restaurants wanting to be featured on the app. Restaurants Without a previous track record of customer orders or the completed app, Rezvani and Rajah were having trouble finding interested restaurants. Restaurants were hesitant to get on board without any proof that their sales would actually increase because all orders made through the app would cost the restaurant 25 per cent of the total food purchaseu Munch's commission on each restaurant's sale. It was important to recruit a wide variety of restaurants to encourage students to use the app. All restaurant customers were contacted directly by Rezvani and Rajah with the hope that the students' belief in the success of the app would help convince restaurant owners to try using it. The pair planned to target popular, locally owned, student-oriented restaurants first, believing that these restaurants were more likely than chain restaurants to try something new. PROJECTIONS Sales After surveying the student body, Rezvani and Rajah determined early on that it was most likely that students would order either by themselves or with only one other individual. Of the total projected orders, it was estimated that 50 per cent would be attributed to restaurant sales, 10 per cent to alcohol, and 40 per cent to snacks. In each of these categories, half of the orders would be for one person and the other half would be for two (see Exhibit 1). Due to the re-order nature of the app and the expectations for growth, the pair understood that during the first three years of operations, sales would likely vary considerably from month to month. After speaking with several small-business owners in the area regarding their early sales and researching the experiences of other app-based delivery services, they concluded that they would likely experience more growth during the months when students were in school compared to the summer months (see Exhibit 2). All transactions were paid by credit card. In order to process these transactions, uMunch contracted Stripe, a third-party credit card processing company. All consumer payments would be managed by Stripe, which would then deposit the funds directly to uMunch on a semi-monthly basis. All restaurants featured on the app would be paid directly by Stripe on the same day as u Munch. Stripe charged 30 cents per credit card used in each transaction plus 2.9 per cent of every sale. All transaction fees would be covered by Munch in full. The app's semi-monthly inflows would be net of these transaction fees. To complete these deliveries, another third-party company, Debb Delivery (Debb), would be contracted. In order to allow for the legal delivery of alcohol, Debb's drivers would be Smart Serve Certified. When a delivery driver picked up a restaurant order, the driver would be paid immediately for the delivery charge by the restaurant Restaurant delivery fees of $6 were included in the total transaction paid by the customer. The delivery fee and 75 per cent of the food order would be paid directly to the restaurant through Stripe. When the delivery driver delivered an alcohol or snack order, the driver would first need to travel to the LCBO or partner convenience store and purchase the item(s) with his own money. Since the delivery driver would not have to wait for food to be prepared in these instances, the delivery fee was lower, at $5 per delivery. Both the delivery fee and the cost of the alcohol and/or snacks would be paid to Debb on the first of the following month. Debb would then distribute the funds accordingly to the delivery drivers. Advertising Marketing would play a critical role in the growth of Munch. Over the course of the first three years of operations, the founders intended to advertise using Facebook and Instagram, and by distributing information about the app on postcards through a direct-mail campaign. In year one, $3,000 was budgeted toward marketing. Of the total advertising budget, Facebook and Instagram would represent 90 per cent, and postcards would represent the remaining 10 per cent. In years two and three, the budget would increase to $6,000 and $9,000, respectively. Advertising expenses were expected to be incurred evenly between the months of August and March each year, and would be paid in the same month. Other Costs A small office space in London had been located for Rezvani and Rajah to begin running their operations. Rent was $1,000 per month with no deposit for last month's rent required. To launch operations, the office would require $3,000 for furniture, $4,500 for office electronics (computers and printers), and $300 for office supplies.* The office furniture was estimated to have a useful life of eight years and the office electronics four years. Both would be depreciated using the straight-line method with no residual value. Utilities, Internet, and phone would cost $65, $128, and $135 per month, respectively, paid for the following month. Annual insurance would amount to $600 and would be paid in full each September. The initial app development and recurring maintenance would need to be outsourced. Rezvani and Rajah contacted a local developer who was willing and able to take on the project. Initial development would cost $85,000, and recurring maintenance would total $12,000 annually. The initial development fee would be paid in full in September, 2018, while the recurring maintenance charges would be paid for in equal monthly installments, beginning in September 2018. During the first three years of operations, Rezvani and Rajah would each need to draw a $1,500 per month salary to cover their living expenses. After the first three years, they would either increase this wage or need to find other employment to supplement their income. During year one, the two owners intended to manage all operations of the business. In addition, uMunch would incur $2,300 in legal fees and $200 of server maintenance fees each September. A $30,000 line of credit had been secured by Rezvani and Rajah to be used in the event that they incurred any cash shortages. The line of credit had an annual interest rate of eight per cent with interest payments due on the first of the following month. After discussions with the bank, the founders understood that it was unlikely that the line of credit would be extended beyond $30,000. Taxes would be paid the following October of each fiscal year at a tax rate of 15 per cent. CONCLUSION After projecting three years of financial statements, Rezvani and Rajah intended to analyze the results and assess the risk of the new business by looking at their margin of safety and return on investment, which would also help with their government grant application. The two planned to launch uMunch in September 2018, and they wondered if it would be possible to launch at all if their grant application were not approved. EXHIBIT 1: AVERAGE ORDER PRICING | Type of Order Restaurant Number of Customers | Average Total Order ($)* 1 20 30 1 L 40 Alcohol 2 65 Snacks** 1 2 11 18 Note: *Average total order includes the cost of delivery; **Snacks cost u Munch an average of $4 per person. Source: Company files EXHIBIT 2: PROJECTED TOTAL MONTHLY APP ORDERS September October November December January February March April May June July August 2019 200 400 800 1,600 1,840 2,080 2,320 2,560 640 640 640 640 2020 2,560 2,800 3,040 3,280 3,520 3,760 4,000 4,240 1,060 1,060 1.060 1.060 2021 4,240 4,400 4,560 4,720 4,880 5,040 5,200 5,360 1,340 1,340 1.340 1,340 Source: Company files. in, they could add the items to their mobile shopping cart, and then share the cart with friends. The friends would then add their meals to the same cart and the app would automatically split the delivery cost among the members of the cart. All cart-sharers would be required to order from the same restaurant in order for there to be only one delivery charge. Because of the strict regulations on alcohol sales in Ontario, alcohol delivery did not earn Munch a profit. Rather, alcohol delivery was a service that Rezvani and Rajah considered would entice students to download the app. They hoped that these students would use and recommend the app to friends in the future. Alcohol was sold on the app for the same amount individuals could purchase it for at the LCBO, plus a delivery fee that would be remitted entirely to the delivery drivers by Munch. The app would be available to download free of charge from the Apple App Store. After the app gained popularity and the founders raised additional funds, they planned to create an Android version of the app to be released on the Google Play Store. CONSUMERS The app had to have a high number of daily users and offer a wide variety of restaurants, snack, and alcohol options. Without each other, neither restaurants nor students would be interested in using the app. It was therefore important that the two founders kept both consumer groups' wants and needs in mind when launching the app. Students Rezvani and Rajah anticipated that students would make up the bulk of their end consumers, given that these individuals were the most likely to eat regularly with people outside of their immediate family. The cart-sharing feature to split delivery costs would not be as desirable to families or couples given that they would more than likely be paying on one bill anyway. Within London, Ontario, there were over 50,000 students who attended Western University and Fanshawe College. The pair planned to target all advertisements at these individuals and host as many on-campus events as possible to get the word out. They anticipated that more student downloads would likely translate into more local restaurants wanting to be featured on the app. Restaurants Without a previous track record of customer orders or the completed app, Rezvani and Rajah were having trouble finding interested restaurants. Restaurants were hesitant to get on board without any proof that their sales would actually increase because all orders made through the app would cost the restaurant 25 per cent of the total food purchaseu Munch's commission on each restaurant's sale. It was important to recruit a wide variety of restaurants to encourage students to use the app. All restaurant customers were contacted directly by Rezvani and Rajah with the hope that the students' belief in the success of the app would help convince restaurant owners to try using it. The pair planned to target popularStep by Step Solution

There are 3 Steps involved in it

Step: 1

Get Instant Access to Expert-Tailored Solutions

See step-by-step solutions with expert insights and AI powered tools for academic success

Step: 2

Step: 3

Ace Your Homework with AI

Get the answers you need in no time with our AI-driven, step-by-step assistance

Get Started