1. Focusing on only the impatient care cost (i.e., ignoring operating room costs), what is the cost of a TAH (non-oncology) under each of the cost accounting systems? a tuboplasty? A TAH (oncology)? What accounts for the differences?

1. Focusing on only the impatient care cost (i.e., ignoring operating room costs), what is the cost of a TAH (non-oncology) under each of the cost accounting systems? a tuboplasty? A TAH (oncology)? What accounts for the differences?

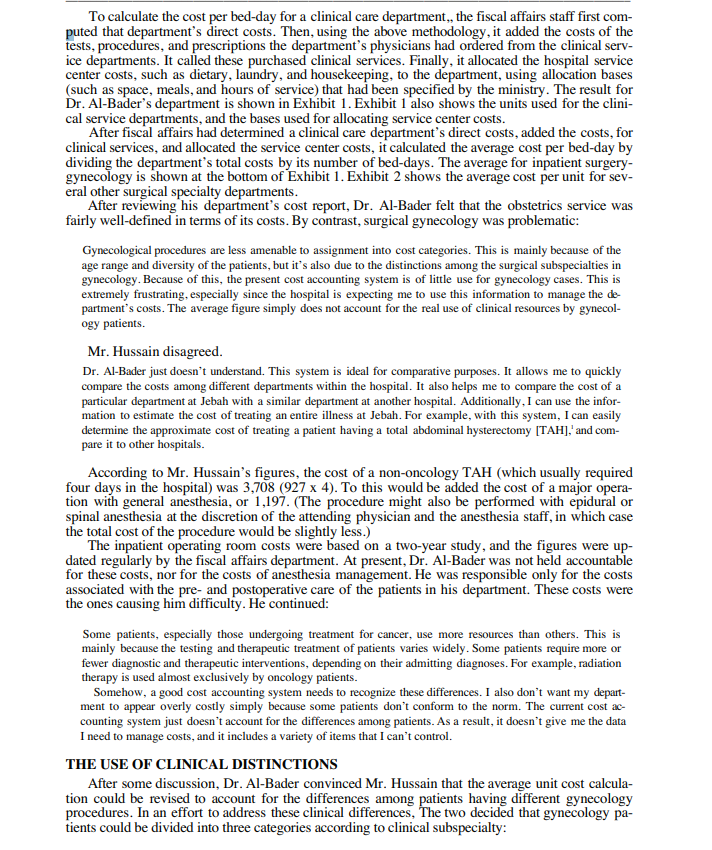

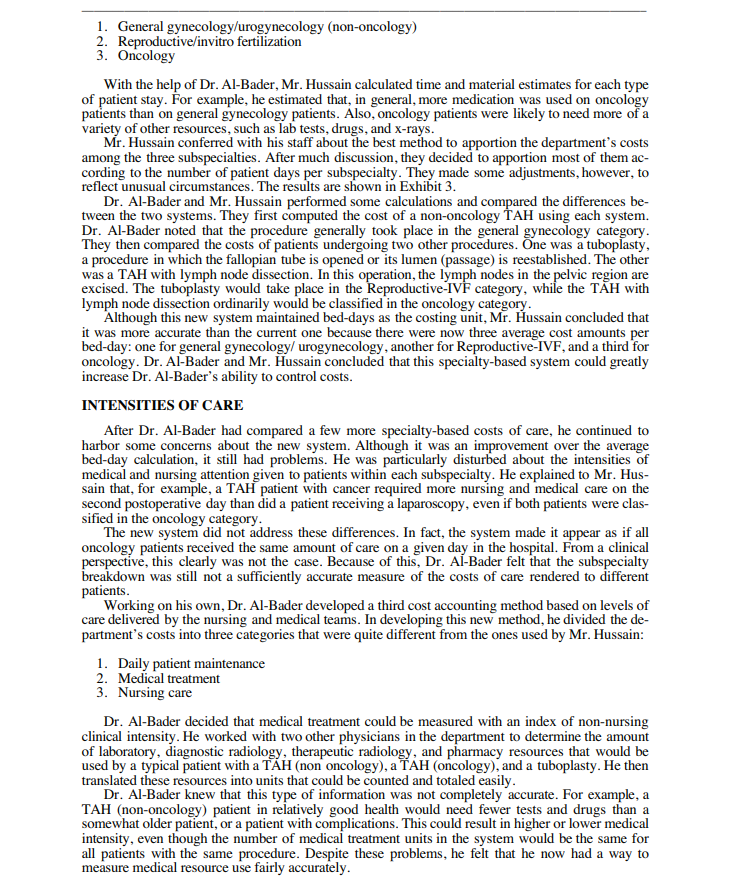

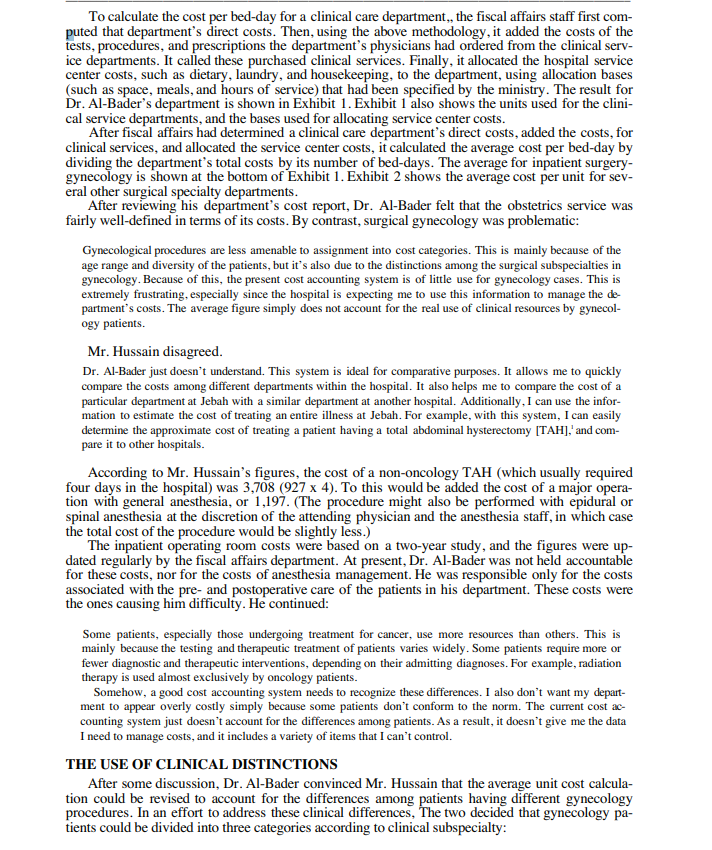

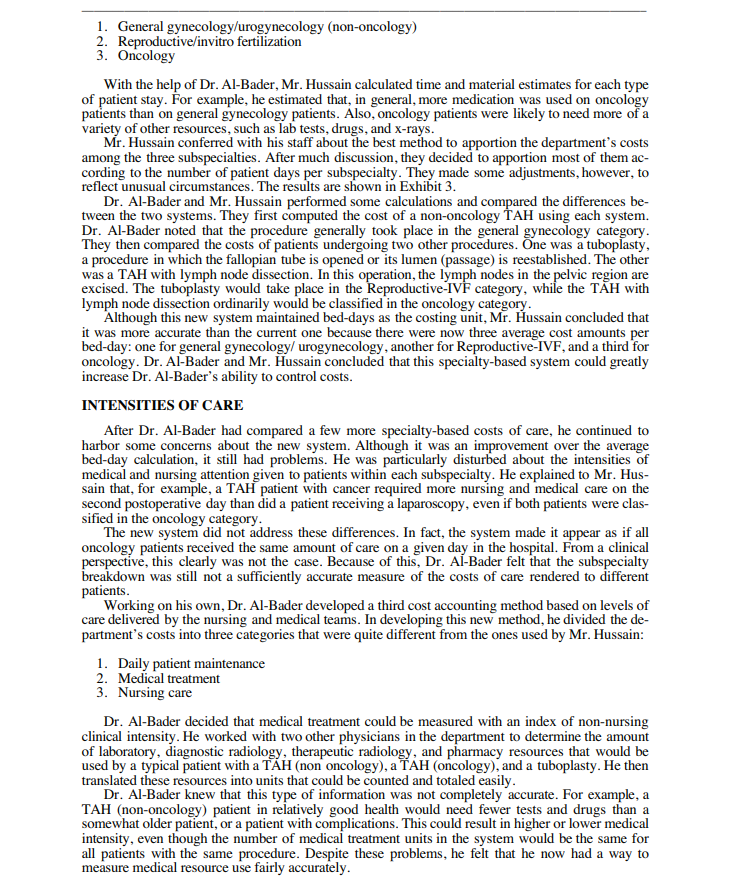

Jebah Hospital This report doesn't describe where our costs are generated. We're applying one standard to all patients, regard- less of their level of care. What incentive is there to identify and account for the costs of each type of proce- dure? Unless I have better cost information, all our attempts to control costs will focus on decreasing the num- ber of days spent in the hospital. This limits our options. In fact, it's not even an appropriate response to the ministry's financial constraints. The speaker was Abdul Al-Bader, M.D., Chief of the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecol- ogy at Jebah Hospital, a medium-sized tertiary care facility, located in a Middle Eastern country. After reviewing the most recent cost report for his department, Dr. Al-Bader had some serious con- cerns, and was meeting with Tarek Hussain, the Director of Fiscal Affairs, whose department had generated the report. Dr. Al-Bader continued: Not only that, but over half the costs are outside my control. How am I supposed to exert any influence over dietary or housekeeping, for example? I also know from experience that the cost figure the hospital is using for a simple lab test, such as a CBC, is exorbitant. And it's likely that some of the other clinical services shown on my report are too expensive as well. But I can't do anything about it! BACKGROUND Two years ago, in an effort to control rising hospital costs, the Ministry of Health had estab- lished countrywide spending limits, and had made each hospital responsible for keeping its total he limit determined during annual budget negotiations. Jebah, like many other tertiary care institutions, had felt the pinch. As one of the country's largest institutions, it had been among the first to establish a departmental cost accounting system. In addition, and with support of its medical staff leadership, Jebah had required each service chief to become involved in the hospi- tal's budgeting process, and to take responsibility for the costs associated with the care of patients in his or her department. By involving service chiefs in the budgeting and control process, Jebah's senior management hoped to gain more control over its costs, and to improve the hospital's overall financial performance. THE COST ACCOUNTING SYSTEM Jebah's cost accounting system was based on three costing units that had been stipulated by the ministry: a bed-day for inpatient care, a visit for outpatient care, and a procedure (or operation) for operating rooms. Each hospital was required to compute its unit costs, such as a cost-per-bed-per- day for inpatient care, and report them to the ministry on a monthly basis. The ministry planned to use the information for cross-hospital cost comparisons, and it expected each hospital to make cross-department comparisons as part of its cost-control efforts. Under Mr. Hussain's leadership, Jebah had taken an additional step. In addition to using the ministry's standard costing units for its clinical care departments (such as Ob-Gyn), it had begun or its clinical service departments, such as radiology, laboratory, radiotherapy and the pharmacy. In radiology and radiotherapy, for example, the unit was a procedure, and Mr. Hussain's staff computed an average cost per procedure each month. The monthly radiology and radiotherapy costs for each clinical care department then were computed by multiplying this average by the number of procedures its physicians had ordered that month. The same was true in the labo- ratory, where the unit was a test, and in the pharmacy, where it was a filled prescription. To calculate the cost per bed-day for a clinical care department, the fiscal affairs staff first com- puted that department's direct costs. Then, using the above methodology, it added the costs of the tests, procedures, and prescriptions the department's physicians had ordered from the clinical serv- ice departments. It called these purchased clinical services. Finally, it allocated the hospital service center costs, such as dietary, laundry, and housekeeping, to the department, using allocation bases (such as space, meals, and hours of service) that had been specified by the ministry. The result for Dr. Al-Bader's department is shown in Exhibit 1. Exhibit 1 also shows the units used for the clini- cal service departments, and the bases used for allocating service center costs. After fiscal affairs had determined a clinical care department's direct costs, added the costs, for clinical services, and allocated the service center costs, it calculated the average cost per bed-day by dividing the department's total costs by its number of bed-days. The average for inpatient surgery- gynecology is shown at the bottom of Exhibit 1. Exhibit 2 shows the average cost per unit for sev- eral other surgical specialty departments. After reviewing his department's cost report, Dr. Al-Bader felt that the obstetrics service was fairly well-defined in terms of its costs. By contrast, surgical gynecology was problematic: Gynecological procedures are less amenable to assignment into cost categories. This is mainly because of the age range and diversity of the patients, but it's also due to the distinctions among the surgical subspecialties in gynecology. Because of this, the present cost accounting system is of little use for gynecology cases. This is extremely frustrating, especially since the hospital is expecting me to use this information to manage the de partment's costs. The average figure simply does not account for the real use of clinical resources by gynecol- ogy patients. Mr. Hussain disagreed. Dr. Al-Bader just doesn't understand. This system is ideal for comparative purposes. It allows me to quickly compare the costs among different departments within the hospital. It also helps me to compare the cost of a particular department at Jebah with a similar department at another hospital. Additionally, I can use the infor- mation to estimate the cost of treating an entire illness at Jebah. For example, with this system, I can easily determine the approximate cost of treating a patient having a total abdominal hysterectomy [TAH],' and com- pare it to other hospitals. According to Mr. Hussain's figures, the cost of a non-oncology TAH (which usually required four days in the hospital) was 3,708 (927 x 4). To this would be added the cost of a major opera- tion with general anesthesia, or 1,197. (The procedure might also be performed with epidural or spinal anesthesia at the discretion of the attending physician and the anesthesia staff, in which case the total cost of the procedure would be slightly less.) The inpatient operating room costs were based on a two-year study, and the figures were up- dated regularly by the fiscal affairs department. At present, Dr. Al-Bader was not held accountable for these costs, nor for the costs of anesthesia management. He was responsible only for the costs associated with the pre- and postoperative care of the patients in his department. These costs were the ones causing him difficulty. He continued: Some patients, especially those undergoing treatment for cancer, use more resources than others. This is mainly because the testing and therapeutic treatment of patients varies widely. Some patients require more or fewer diagnostic and therapeutic interventions, depending on their admitting diagnoses. For example, radiation therapy is used almost exclusively by oncology patients. Somehow, a good cost accounting system needs to recognize these differences. I also don't want my depart- ment to appear overly costly simply because some patients don't conform to the norm. The current cost ac counting system just doesn't account for the differences among patients. As a result, it doesn't give me the data I need to manage costs, and it includes a variety of items that I can't control. THE USE OF CLINICAL DISTINCTIONS After some discussion, Dr. Al-Bader convinced Mr. Hussain that the average unit cost calcula- tion could be revised to account for the differences among patients having different gynecology procedures. In an effort to address these clinical differences. The two decided that gynecology pa- tients could be divided into three categories according to clinical subspecialty: 1. General gynecology/urogynecology (non-oncology) 2. Reproductive/invitro fertilization 3. Oncology With the help of Dr. Al-Bader, Mr. Hussain calculated time and material estimates for each type of patient stay. For example, he estimated that, in general, more medication was patients than on general gynecology patients. Also, oncology patients were likely to need more of a variety of other resources, such as lab tests, drugs, and X-rays. Mr. Hussain conferred with his staff about the best method to apportion the department's costs among the three subspecialties. After much discussion, they decided to apportion most of them ac- cording to the number of patient days per subspecialty. They made some adjustments, however, to eflect unusual circumstances. The results are shown in Exhibit 3. Dr. Al-Bader and Mr. Hussain performed some calculations and compared the differences be- tween the two systems. They first computed the cost of a non-oncology TAH using each system. Dr. Al-Bader noted that the procedure generally took place in the general gynecology category. They then compared the costs of patients undergoing two other procedures. One was a tuboplasty, a procedure in which the fallopian tube is opened or its lumen (passage) is reestablished. The other was a TAH with lymph node dissection. In this operation, the lymph nodes in the pelvic region are excised. The tuboplasty would take place in the Reproductive-IVF category, while the TAH with lymph node dissection ordinarily would be classified in the oncology category. Although this new system maintained bed-days as the costing unit, Mr. Hussain concluded that it was more accurate than the current one because there were now three average cost amounts per bed-day: one for general gynecology/ urogynecology, another for Reproductive-IVF, and a third for oncology. Dr. Al-Bader and Mr. Hussain concluded that this specialty-based system could greatly increase Dr. Al-Bader's ability to control costs. INTENSITIES OF CARE After Dr. Al-Bader had compared a few more specialty-based costs of care, he continued to harbor some concerns about the new system. Although it was an improvement over the average bed-day calculation, it still had problems. He was particularly disturbed about the intensities of medical and nursing attention given to patients within each subspecialty. He explained to Mr. Hus- sain that, for example, a TAH patient with cancer required more nursing and medical care on the second postoperative day than did a patient receiving a laparoscopy, even if both patients were clas- sified in the oncology category. The new system did not address these differences. In fact, the system made it appear as if all oncology patients received the same amount of care on a given day perspective, this clearly was not the case. Because of this, Dr. Al-Bader felt that the subspecialty breakdown was still not a sufficiently accurate measure of the costs of care rendered to different patients. Working on his own, Dr. Al-Bader developed a third cost accounting method based on levels of care delivered by the nursing and medical teams. In developing this new method, he divided the de- partment's costs into three categories that were quite different from the ones used by Mr. Hussain: 1. Daily patient maintenance 2. Medical treatment 3. Nursing care Dr. Al-Bader decided that medical treatment could be measured with an index of non-nursing clinical intensity. He worked with two other physicians in the department to determine the amount of laboratory, diagnostic radiology, therapeutic radiology, and pharmacy resources that would be used by a typical patient with a TAH (non oncology), a TAH (Oncology), and a tuboplasty. He then translated these resources into units that could be counted and totaled easily. Dr. Al-Bader knew that this type of information was not completely accurate. For example, a TAH (non-oncology) patient in relatively good health would need fewer tests and drugs than a somewhat older patient, or a patient with complications. This could result in higher or lower medical intensity, even though the number of medical treatment units in the system would be the same for all patients with the same procedure. Despite these problems, he felt that he now had a way to measure medical resource use fairly accurately. TCG157 Jebah Hospital 4 of 8 Levels of nursing care proved to be similarly complicated. Dr. Al-Bader consulted with nurses on the gynecology floor and, with them, developed a system to measure patient care needs. They defined three basic levels of nursing care, which are described in Exhibit 4. A patient could change levels during her stay, and, within each level, a patient could be assigned a range of units, depending upon the intensity of nursing services being provided. In this third method, Dr. Al-Bader expected to use not only bed-days as a costing unit, but also, the average number of medical treatment units and nursing units per procedure. He enlisted Mr. Hussain's assistance in devising a means to divide costs among the categories in his new system. The resulting cost breakdown is shown in Exhibit 5. COMPARISON OF COSTS To compare his new system with the others, Dr. Al-Bader again calculated costs for the same three procedures. According to his calculations, each required the following: Bed Days Medical Treatment Units Nursing Units 10 Procedure TAH-Non-oncology Tuboplasty TAH-Oncology 20 38 Dr. Al-Bader was satisfied with the results of this cost accounting system. He thought it accu- rately distinguished among the surgical procedures in the gynecological subspecialties, and that the differences in costs reflected the actual differences in resources used by patients. He commented: With this new information, I can identify cost problems easily since all costs are now categorized according to the nature as well as the intensity of the services. I plan to develop this system even further so that standard unit requirements for each type of procedure become well-known by the physicians in my department. Then I'll be able to analyze gynecology costs according to the patient mix being treated, and in terms of the services be- ing provided or ordered by different physicians. Mr. Hussain agreed with Dr. Al-Bader that this third system might work well in gynecology, and in other departments having surgical subspecialties. However, he doubted that it could be tr ferred to all departments within the hospital. He felt that some departments would not be able to de- velop standard medical and nursing requirements since their patient diagnoses and procedures were less well-defined than those in surgery. Furthermore, he was concerned about the complexity of the system, especially for department chiefs. Chiefs, in his view, might not have the inclination or ability to use the system effectively, or might not feel it worth the time to collect all of the necessary infor- mation. Dr. Al-Bader disagreed. He contacted the Vice President of Medical Affairs and offered to pre- sent his system at the next meeting of chiefs of service. He was convinced that the chiefs would see its value. Assignment 1. Focusing on only the inpatient care cost i.e., ignoring operating room costs), what is the cost of a TAH (non-oncology) under each of the cost accounting systems? A tuboplasty? A TAH (Oncology)? What a counts for the differences? 2. Which of the three systems is the best? Why? 3. From a managerial perspective, of what use is the information in the second and third systems? How, if at all, would this additional information improve Dr. Al-Bader's ability to control costs? How might it help chiefs in non-surgical specialties? 4. What should Dr. Al-Bader do next? JEBAH HOSPITAL Exhibit 1. Cost Center Report for Inpatient Surgery-Gynecology Direct Costs Wages: Physician services Nursing service Clinical support staff Administrative staff 1,881,160 1,301,170 902,790 4,217,725 Supplies: Medical supplies Administrative supplies 670,050 205,150 875,200 208,000 5,300,925 4,409,476 Capital Depreciation on maior purchases 174.000 Equipment: Minor purchases 34,000 Total direct costs Purchased Clinical Services Costing Unit Diagnostic imaging Procedure 687,361 Laboratory tests Test 923,986 Radiotherapy Procedure 279,486 Pharmaceutical Prescription 2.518.643 Allocated Service Center Costs Allocation Basis Patient Dietary Meal 626,430 Services: Laundry Kilogram 169,575 Housekeeping Square meter 154,260 Medical records Record 127.720 Social Service Hour of service 120.897 General Operation of plant Square meter 236,450 Services Plant depreciation Square meter 382.680 Employee benefits Salaries 469.950 Administration No. employees 1.000,300 Insurance Square meter 541,000 Total purchased and allocated costs Total costs Average cost per day 1 ,198,882 2,630,380 8,238,738 13,539,663 927 819 Exhibit 2. Cost Summary for Surgical Specialties and Anesthesia Inpatient Cost by Specialty Costing Unit Total Cost Average/Unit General bed/day 11,871,305 797 Orthopedic bed/day 12,274,636 938 Neurosurgery bed/day 15,837,594 1.106 Gynecology bed/day 13,539,663 927 Obstetrics bed/day 9,483,625 Pediatrics bed/day 11,847,364 882 Total Inpatient 74.854.187 Anesthesia in Inpatient Operating Rooms 13,789,475 Major/General procedure 1,197 Major/Epidural or Spinal procedure 1,163 Major/Local or Regional procedure 760 Minor/General procedure 589 Minor/Epidural or Spinal procedure 485 Minor/Local or Regional procedure 274 Anesthesia in Emergency Operating Rooms 4,842.631 Minor/General Anesthesia procedure Minor/Local or Regional procedure Minor/No anesthesia procedure Total Cost 93,486,293 JEBAH HOSPITAL EXHIBIT 4. Levels of Nursing Care Level 1 Basic Assistance (mainly for ambulatory patients) 1-3 units Feeds self without supervision or with family member. Toilets independently. Vital signs routine - daily temperature, pulse and respiration. Bedside humidifier or blow bottle. Routine post-operation suction standby. Bathes self, bed straightened with minimal or no supervision. Exercises with assistance, once in 8 hours. Treatments once or twice in 8 hours. Level 2 Periodic Assistance 4-7 units Feeds self with staff supervision; I&O; or tubal feeding by patient. Toilets with supervision or specimen collection, or uses bedpan. Hemovac output. Vital signs monitored; every 2 to 4 hours. Mist or humidified air when sleeping, or cough and deep breathe every 2 hours. Nasopharyngeal or oral suction prn. Bathed and dressed by personnel or partial bath given; daily change of linen. Up in chair with assistance twice in 8 hours or walking with assistance. Treatments 3 or 4 times in 8 hours. Level 3 Continual Nursing Care 8-10 units Total feeding by personnel or continuous IV or blood transfusions or instructing the patient. Tube feeding by personnel every 3 hours or less. Up to toilet with standby supervision or output measurement every hour. Initial hemovac setup. Vital signs and observation every hour or vital signs monitored plus neuro check. Blood pressure, pulse, respiration and neuro check every 30 minutes. Continuous oxygen, trach mist or cough and deep breathe every hour. IPPB with supervision every 4 hours. Tracheostomy suction every 2 hours or less. Bathed and dressed by personnel, special skin care, occupied bed. Bed rest with assistance in turning every 2 hours or less, or walking with assistance of two persons twice in 8 hours. Treatments more than every 2 hours. Jebah Hospital This report doesn't describe where our costs are generated. We're applying one standard to all patients, regard- less of their level of care. What incentive is there to identify and account for the costs of each type of proce- dure? Unless I have better cost information, all our attempts to control costs will focus on decreasing the num- ber of days spent in the hospital. This limits our options. In fact, it's not even an appropriate response to the ministry's financial constraints. The speaker was Abdul Al-Bader, M.D., Chief of the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecol- ogy at Jebah Hospital, a medium-sized tertiary care facility, located in a Middle Eastern country. After reviewing the most recent cost report for his department, Dr. Al-Bader had some serious con- cerns, and was meeting with Tarek Hussain, the Director of Fiscal Affairs, whose department had generated the report. Dr. Al-Bader continued: Not only that, but over half the costs are outside my control. How am I supposed to exert any influence over dietary or housekeeping, for example? I also know from experience that the cost figure the hospital is using for a simple lab test, such as a CBC, is exorbitant. And it's likely that some of the other clinical services shown on my report are too expensive as well. But I can't do anything about it! BACKGROUND Two years ago, in an effort to control rising hospital costs, the Ministry of Health had estab- lished countrywide spending limits, and had made each hospital responsible for keeping its total he limit determined during annual budget negotiations. Jebah, like many other tertiary care institutions, had felt the pinch. As one of the country's largest institutions, it had been among the first to establish a departmental cost accounting system. In addition, and with support of its medical staff leadership, Jebah had required each service chief to become involved in the hospi- tal's budgeting process, and to take responsibility for the costs associated with the care of patients in his or her department. By involving service chiefs in the budgeting and control process, Jebah's senior management hoped to gain more control over its costs, and to improve the hospital's overall financial performance. THE COST ACCOUNTING SYSTEM Jebah's cost accounting system was based on three costing units that had been stipulated by the ministry: a bed-day for inpatient care, a visit for outpatient care, and a procedure (or operation) for operating rooms. Each hospital was required to compute its unit costs, such as a cost-per-bed-per- day for inpatient care, and report them to the ministry on a monthly basis. The ministry planned to use the information for cross-hospital cost comparisons, and it expected each hospital to make cross-department comparisons as part of its cost-control efforts. Under Mr. Hussain's leadership, Jebah had taken an additional step. In addition to using the ministry's standard costing units for its clinical care departments (such as Ob-Gyn), it had begun or its clinical service departments, such as radiology, laboratory, radiotherapy and the pharmacy. In radiology and radiotherapy, for example, the unit was a procedure, and Mr. Hussain's staff computed an average cost per procedure each month. The monthly radiology and radiotherapy costs for each clinical care department then were computed by multiplying this average by the number of procedures its physicians had ordered that month. The same was true in the labo- ratory, where the unit was a test, and in the pharmacy, where it was a filled prescription. To calculate the cost per bed-day for a clinical care department, the fiscal affairs staff first com- puted that department's direct costs. Then, using the above methodology, it added the costs of the tests, procedures, and prescriptions the department's physicians had ordered from the clinical serv- ice departments. It called these purchased clinical services. Finally, it allocated the hospital service center costs, such as dietary, laundry, and housekeeping, to the department, using allocation bases (such as space, meals, and hours of service) that had been specified by the ministry. The result for Dr. Al-Bader's department is shown in Exhibit 1. Exhibit 1 also shows the units used for the clini- cal service departments, and the bases used for allocating service center costs. After fiscal affairs had determined a clinical care department's direct costs, added the costs, for clinical services, and allocated the service center costs, it calculated the average cost per bed-day by dividing the department's total costs by its number of bed-days. The average for inpatient surgery- gynecology is shown at the bottom of Exhibit 1. Exhibit 2 shows the average cost per unit for sev- eral other surgical specialty departments. After reviewing his department's cost report, Dr. Al-Bader felt that the obstetrics service was fairly well-defined in terms of its costs. By contrast, surgical gynecology was problematic: Gynecological procedures are less amenable to assignment into cost categories. This is mainly because of the age range and diversity of the patients, but it's also due to the distinctions among the surgical subspecialties in gynecology. Because of this, the present cost accounting system is of little use for gynecology cases. This is extremely frustrating, especially since the hospital is expecting me to use this information to manage the de partment's costs. The average figure simply does not account for the real use of clinical resources by gynecol- ogy patients. Mr. Hussain disagreed. Dr. Al-Bader just doesn't understand. This system is ideal for comparative purposes. It allows me to quickly compare the costs among different departments within the hospital. It also helps me to compare the cost of a particular department at Jebah with a similar department at another hospital. Additionally, I can use the infor- mation to estimate the cost of treating an entire illness at Jebah. For example, with this system, I can easily determine the approximate cost of treating a patient having a total abdominal hysterectomy [TAH],' and com- pare it to other hospitals. According to Mr. Hussain's figures, the cost of a non-oncology TAH (which usually required four days in the hospital) was 3,708 (927 x 4). To this would be added the cost of a major opera- tion with general anesthesia, or 1,197. (The procedure might also be performed with epidural or spinal anesthesia at the discretion of the attending physician and the anesthesia staff, in which case the total cost of the procedure would be slightly less.) The inpatient operating room costs were based on a two-year study, and the figures were up- dated regularly by the fiscal affairs department. At present, Dr. Al-Bader was not held accountable for these costs, nor for the costs of anesthesia management. He was responsible only for the costs associated with the pre- and postoperative care of the patients in his department. These costs were the ones causing him difficulty. He continued: Some patients, especially those undergoing treatment for cancer, use more resources than others. This is mainly because the testing and therapeutic treatment of patients varies widely. Some patients require more or fewer diagnostic and therapeutic interventions, depending on their admitting diagnoses. For example, radiation therapy is used almost exclusively by oncology patients. Somehow, a good cost accounting system needs to recognize these differences. I also don't want my depart- ment to appear overly costly simply because some patients don't conform to the norm. The current cost ac counting system just doesn't account for the differences among patients. As a result, it doesn't give me the data I need to manage costs, and it includes a variety of items that I can't control. THE USE OF CLINICAL DISTINCTIONS After some discussion, Dr. Al-Bader convinced Mr. Hussain that the average unit cost calcula- tion could be revised to account for the differences among patients having different gynecology procedures. In an effort to address these clinical differences. The two decided that gynecology pa- tients could be divided into three categories according to clinical subspecialty: 1. General gynecology/urogynecology (non-oncology) 2. Reproductive/invitro fertilization 3. Oncology With the help of Dr. Al-Bader, Mr. Hussain calculated time and material estimates for each type of patient stay. For example, he estimated that, in general, more medication was patients than on general gynecology patients. Also, oncology patients were likely to need more of a variety of other resources, such as lab tests, drugs, and X-rays. Mr. Hussain conferred with his staff about the best method to apportion the department's costs among the three subspecialties. After much discussion, they decided to apportion most of them ac- cording to the number of patient days per subspecialty. They made some adjustments, however, to eflect unusual circumstances. The results are shown in Exhibit 3. Dr. Al-Bader and Mr. Hussain performed some calculations and compared the differences be- tween the two systems. They first computed the cost of a non-oncology TAH using each system. Dr. Al-Bader noted that the procedure generally took place in the general gynecology category. They then compared the costs of patients undergoing two other procedures. One was a tuboplasty, a procedure in which the fallopian tube is opened or its lumen (passage) is reestablished. The other was a TAH with lymph node dissection. In this operation, the lymph nodes in the pelvic region are excised. The tuboplasty would take place in the Reproductive-IVF category, while the TAH with lymph node dissection ordinarily would be classified in the oncology category. Although this new system maintained bed-days as the costing unit, Mr. Hussain concluded that it was more accurate than the current one because there were now three average cost amounts per bed-day: one for general gynecology/ urogynecology, another for Reproductive-IVF, and a third for oncology. Dr. Al-Bader and Mr. Hussain concluded that this specialty-based system could greatly increase Dr. Al-Bader's ability to control costs. INTENSITIES OF CARE After Dr. Al-Bader had compared a few more specialty-based costs of care, he continued to harbor some concerns about the new system. Although it was an improvement over the average bed-day calculation, it still had problems. He was particularly disturbed about the intensities of medical and nursing attention given to patients within each subspecialty. He explained to Mr. Hus- sain that, for example, a TAH patient with cancer required more nursing and medical care on the second postoperative day than did a patient receiving a laparoscopy, even if both patients were clas- sified in the oncology category. The new system did not address these differences. In fact, the system made it appear as if all oncology patients received the same amount of care on a given day perspective, this clearly was not the case. Because of this, Dr. Al-Bader felt that the subspecialty breakdown was still not a sufficiently accurate measure of the costs of care rendered to different patients. Working on his own, Dr. Al-Bader developed a third cost accounting method based on levels of care delivered by the nursing and medical teams. In developing this new method, he divided the de- partment's costs into three categories that were quite different from the ones used by Mr. Hussain: 1. Daily patient maintenance 2. Medical treatment 3. Nursing care Dr. Al-Bader decided that medical treatment could be measured with an index of non-nursing clinical intensity. He worked with two other physicians in the department to determine the amount of laboratory, diagnostic radiology, therapeutic radiology, and pharmacy resources that would be used by a typical patient with a TAH (non oncology), a TAH (Oncology), and a tuboplasty. He then translated these resources into units that could be counted and totaled easily. Dr. Al-Bader knew that this type of information was not completely accurate. For example, a TAH (non-oncology) patient in relatively good health would need fewer tests and drugs than a somewhat older patient, or a patient with complications. This could result in higher or lower medical intensity, even though the number of medical treatment units in the system would be the same for all patients with the same procedure. Despite these problems, he felt that he now had a way to measure medical resource use fairly accurately. TCG157 Jebah Hospital 4 of 8 Levels of nursing care proved to be similarly complicated. Dr. Al-Bader consulted with nurses on the gynecology floor and, with them, developed a system to measure patient care needs. They defined three basic levels of nursing care, which are described in Exhibit 4. A patient could change levels during her stay, and, within each level, a patient could be assigned a range of units, depending upon the intensity of nursing services being provided. In this third method, Dr. Al-Bader expected to use not only bed-days as a costing unit, but also, the average number of medical treatment units and nursing units per procedure. He enlisted Mr. Hussain's assistance in devising a means to divide costs among the categories in his new system. The resulting cost breakdown is shown in Exhibit 5. COMPARISON OF COSTS To compare his new system with the others, Dr. Al-Bader again calculated costs for the same three procedures. According to his calculations, each required the following: Bed Days Medical Treatment Units Nursing Units 10 Procedure TAH-Non-oncology Tuboplasty TAH-Oncology 20 38 Dr. Al-Bader was satisfied with the results of this cost accounting system. He thought it accu- rately distinguished among the surgical procedures in the gynecological subspecialties, and that the differences in costs reflected the actual differences in resources used by patients. He commented: With this new information, I can identify cost problems easily since all costs are now categorized according to the nature as well as the intensity of the services. I plan to develop this system even further so that standard unit requirements for each type of procedure become well-known by the physicians in my department. Then I'll be able to analyze gynecology costs according to the patient mix being treated, and in terms of the services be- ing provided or ordered by different physicians. Mr. Hussain agreed with Dr. Al-Bader that this third system might work well in gynecology, and in other departments having surgical subspecialties. However, he doubted that it could be tr ferred to all departments within the hospital. He felt that some departments would not be able to de- velop standard medical and nursing requirements since their patient diagnoses and procedures were less well-defined than those in surgery. Furthermore, he was concerned about the complexity of the system, especially for department chiefs. Chiefs, in his view, might not have the inclination or ability to use the system effectively, or might not feel it worth the time to collect all of the necessary infor- mation. Dr. Al-Bader disagreed. He contacted the Vice President of Medical Affairs and offered to pre- sent his system at the next meeting of chiefs of service. He was convinced that the chiefs would see its value. Assignment 1. Focusing on only the inpatient care cost i.e., ignoring operating room costs), what is the cost of a TAH (non-oncology) under each of the cost accounting systems? A tuboplasty? A TAH (Oncology)? What a counts for the differences? 2. Which of the three systems is the best? Why? 3. From a managerial perspective, of what use is the information in the second and third systems? How, if at all, would this additional information improve Dr. Al-Bader's ability to control costs? How might it help chiefs in non-surgical specialties? 4. What should Dr. Al-Bader do next? JEBAH HOSPITAL Exhibit 1. Cost Center Report for Inpatient Surgery-Gynecology Direct Costs Wages: Physician services Nursing service Clinical support staff Administrative staff 1,881,160 1,301,170 902,790 4,217,725 Supplies: Medical supplies Administrative supplies 670,050 205,150 875,200 208,000 5,300,925 4,409,476 Capital Depreciation on maior purchases 174.000 Equipment: Minor purchases 34,000 Total direct costs Purchased Clinical Services Costing Unit Diagnostic imaging Procedure 687,361 Laboratory tests Test 923,986 Radiotherapy Procedure 279,486 Pharmaceutical Prescription 2.518.643 Allocated Service Center Costs Allocation Basis Patient Dietary Meal 626,430 Services: Laundry Kilogram 169,575 Housekeeping Square meter 154,260 Medical records Record 127.720 Social Service Hour of service 120.897 General Operation of plant Square meter 236,450 Services Plant depreciation Square meter 382.680 Employee benefits Salaries 469.950 Administration No. employees 1.000,300 Insurance Square meter 541,000 Total purchased and allocated costs Total costs Average cost per day 1 ,198,882 2,630,380 8,238,738 13,539,663 927 819 Exhibit 2. Cost Summary for Surgical Specialties and Anesthesia Inpatient Cost by Specialty Costing Unit Total Cost Average/Unit General bed/day 11,871,305 797 Orthopedic bed/day 12,274,636 938 Neurosurgery bed/day 15,837,594 1.106 Gynecology bed/day 13,539,663 927 Obstetrics bed/day 9,483,625 Pediatrics bed/day 11,847,364 882 Total Inpatient 74.854.187 Anesthesia in Inpatient Operating Rooms 13,789,475 Major/General procedure 1,197 Major/Epidural or Spinal procedure 1,163 Major/Local or Regional procedure 760 Minor/General procedure 589 Minor/Epidural or Spinal procedure 485 Minor/Local or Regional procedure 274 Anesthesia in Emergency Operating Rooms 4,842.631 Minor/General Anesthesia procedure Minor/Local or Regional procedure Minor/No anesthesia procedure Total Cost 93,486,293 JEBAH HOSPITAL EXHIBIT 4. Levels of Nursing Care Level 1 Basic Assistance (mainly for ambulatory patients) 1-3 units Feeds self without supervision or with family member. Toilets independently. Vital signs routine - daily temperature, pulse and respiration. Bedside humidifier or blow bottle. Routine post-operation suction standby. Bathes self, bed straightened with minimal or no supervision. Exercises with assistance, once in 8 hours. Treatments once or twice in 8 hours. Level 2 Periodic Assistance 4-7 units Feeds self with staff supervision; I&O; or tubal feeding by patient. Toilets with supervision or specimen collection, or uses bedpan. Hemovac output. Vital signs monitored; every 2 to 4 hours. Mist or humidified air when sleeping, or cough and deep breathe every 2 hours. Nasopharyngeal or oral suction prn. Bathed and dressed by personnel or partial bath given; daily change of linen. Up in chair with assistance twice in 8 hours or walking with assistance. Treatments 3 or 4 times in 8 hours. Level 3 Continual Nursing Care 8-10 units Total feeding by personnel or continuous IV or blood transfusions or instructing the patient. Tube feeding by personnel every 3 hours or less. Up to toilet with standby supervision or output measurement every hour. Initial hemovac setup. Vital signs and observation every hour or vital signs monitored plus neuro check. Blood pressure, pulse, respiration and neuro check every 30 minutes. Continuous oxygen, trach mist or cough and deep breathe every hour. IPPB with supervision every 4 hours. Tracheostomy suction every 2 hours or less. Bathed and dressed by personnel, special skin care, occupied bed. Bed rest with assistance in turning every 2 hours or less, or walking with assistance of two persons twice in 8 hours. Treatments more than every 2 hours

1. Focusing on only the impatient care cost (i.e., ignoring operating room costs), what is the cost of a TAH (non-oncology) under each of the cost accounting systems? a tuboplasty? A TAH (oncology)? What accounts for the differences?

1. Focusing on only the impatient care cost (i.e., ignoring operating room costs), what is the cost of a TAH (non-oncology) under each of the cost accounting systems? a tuboplasty? A TAH (oncology)? What accounts for the differences?