Question: 1. Over-land can increase capacity in different ways to accommodate the additional loads if they accept FHPs contract. Why might Over-land use an independent operator

1. Over-land can increase capacity in different ways to accommodate the additional loads if they accept FHPs contract. Why might Over-land use an independent operator (variable cost of $1.65/mile) over purchasing a rig and hiring a driver for a lower variable cost ($1.39/mile)? Calculate at what point (in miles) Over-land would be indifferent between purchasing a new rig and using an independent operator.

2. What should Over-land do?? If you were advising Over-land on what to do relative to FHPs two additional routes, what would you advise, and why?

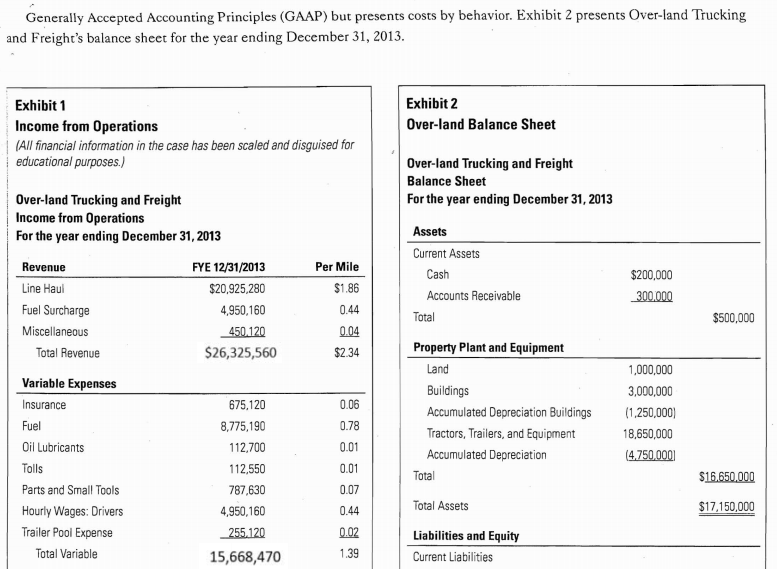

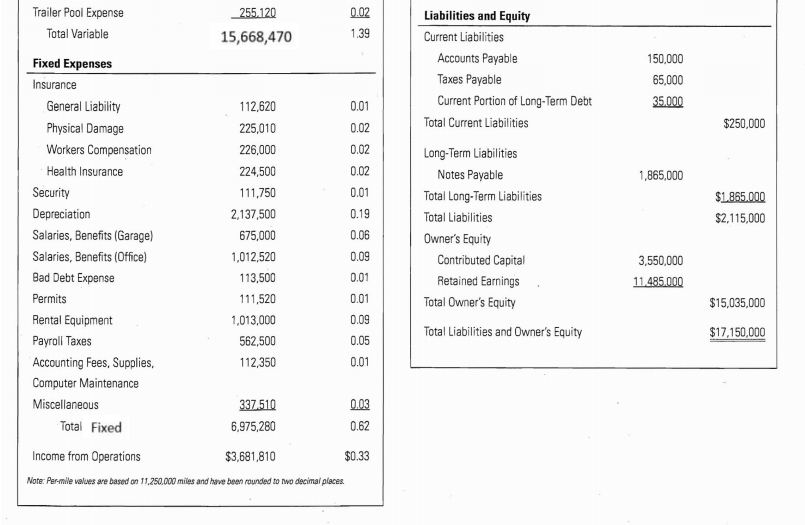

ABSTRACT Over-land Trucking and Freight has a long-established and mutually beneficial business relationship with a major international automotive parts company, FHP Technologies. Management at FHP has approached Over-land with a request to provide additional routes that are important to the efficiency of its supply chain. Over-land's management wishes to nurture the business relationship with FHP but is concerned about the available capacity to service the new routes, potential risks, and profitability associated with FHP's request. INTRODUCTION Alan James founded Over-land Trucking and Freight in 1968 and has grown the business into a sizeable operation with 90 trucks and 180 trailers. His largest customer, FHP Technologies, has submitted a proposal to him to add delivery routes that would improve the efficiency of FHP's supply chain. Alan was not certain that Over-land could handle the additional routes since the company currently was operating at (or near) full capacity. FHP offered a total of $2.15 per mile (including fuel service charge and miscellaneous fees) for the new route. But Alan knew that to accept the offer he would have to add more trucks and perhaps incur additional debt. The question was whether the rates offered by FHP were high enough to offset the associated risks of growing the fleet. Although the business had been grown organically through the years by reinvesting profits, it incurred debt from time to time to replace older equipment (usually in blocks of five trucks). Alan knew the slim profit margins associated with trucking, coupled with a downturn in the economy, could spell disaster if saddled with too much debt. See Exhibits 1 and 2 for the company's most recent statement of income from operations and the balance sheet, respectively. Roger Simmons, Over-land's operations manager for the past 16 years, had been reviewing the FHP proposal and approached Alan. "Alan, we need to discuss this offer from FHP. I think it is a great opportunity for our company, and we need to find a way to make it work." Within 10 minutes Alan and Roger were in a closed-door meeting discussing the pros and cons of FHP's offer. Roger began by stating the obvious: "Alan, this is a huge opportunity for us to grow the business. Not to mention, as FHP becomes more dependent on our services, we will be in a stronger position to negotiate future rate increases. I know you are opposed to debt, and I understand the risks of carrying more debt, but there is more than one way to grow our fleet. If you would consider using independent contract drivers, we could grow the fleet enough to accept FHP's offer without incurring more debt." Alan cringed at the thought of using independent contract drivers. Although independent contractors owned their own trucks, Alan viewed them as difficult to deal with and not worth the headache. "Roger, I hear you, but this new route will not last a week if we cannot give FHP great service. Independent contractors call the shots, not us. They own the rig and will sit at home if they want to. I would rather deal with our own company's rigs and drivers. The rewards just do not justify the risks of damaging our relationship with FHP. Included in miscellaneous revenue are the following: Storage fees are collected when Over-land stores a loaded trailer on its lot for a customer. Lumper revenue is collected if a driver assists with unloading a trailer. "But I am not sure we should take on any more debt at this point to purchase additional rigs. The economy is in the tank, and it is a bad time for us to leverage the balance sheet any further. Roger, my success in this business was not built by jumping on every offer that came along. Sometimes you have to say no, even to your biggest customer. Unless you can find a way to squeeze out more capacity within our current fleet, I just do not think we can accept FHP's offer at this time," Alan concluded. As the two men left the room, Roger was convinced that Alan was wrong. Roger knew that Alan was leaving money on the table. He just needed to prepare a financial analysis that would prove it. Was it possible to squeeze out more capacity from an already fully utilized fleet? Perhaps they could shift trucks from another account. Was taking on more debt truly "risky" given the profit potential of this new route? Roger knew he had to make a convincing argument before FHP took its offer to another truck line. Certain flatbed loads, such as drywall, unpainted steel, and some types of wood products, that would be damaged by rain must be covered. Trucking companies typically charge a tarping fee for such loads. Additional insurance is required when transporting high- value cargo. Practices vary throughout the industry. If a load is above a company's standard cargo insurance limits, many companies simply will not haul it. Trucking companies that are willing to bind additional cargo coverage normally do so for a fee that covers only the extra cost of insurance. (Alternatively, this revenue line item could have been booked as a reduction to the "Insurance" expense account.) INDUSTRY TERMS Loads transported on flatbed trailers must be secured by straps or chains. These types of loads often are associated with higher worker's comp claims. Thus an extra strapping and chaining fee is charged only for a flatbed load. A tractor-trailer rig is a truck that consists of a tractor attached to a trailer. The tractor typically is powered by a diesel engine. A flatbed trailer is long flat platform with no sides. A dry van trailer is a boxed cargo compartment designed for nonrefrigerated freight. Trucking companies often have a revenue-generating load in one direction but need a revenue-generating contract for the return trip. The return trip is known as a backhaul. Often trucking companies contract with freight brokers to acquire backhauls. If a truck sits idle at the dock for more than two hours, customers can be charged a fee that is classified as detention revenue. Placing a detention revenue clause in the contract encourages customers to load trailers efficiently in order to avoid further constraints on Over-land's tractor capacity. TYPES OF BUSINESS ARRANGEMENTS WITH DRIVERS Over-land has potentially two arrangements with drivers. "They are classified as emplosagar as independent operare INDUSTRY BACKGROUND AND COST STRUCTURE Trucking firms generate a variety of revenue types from hauling goods for their clients. Presented next is a brief overview of key types of revenues included in the 2013 income from operations of Over-land Trucking and Freight. Line haul revenue is earned from hauling freight They are classified as employees or as independent operators. Employees receive traditional employee benefits and a Form W2 for tax purposes. These persons are typically engaged in work for the company that is considered "permanent." Alternatively, independent operators are not considered employees and receive a Form 1099 (rather than a Form W2) for tax purposes. These operators typically provide the tractor but generally do not provide the trailer. In addition to driver salaries and depreciation on trucks, expenses incurred by independent contractors include: Tags (known as International Registration Plan (IRP)) - The independent contractor buys the IRP tag for the tractor, while the shipping company buys the tags for the trailer. IRS Form 2290 - Heavy Road Use Tax. Diesel fuel, engine fluids, and all maintenance-related parts and items. Fuel prices in recent years have been volatile. Because trucking companies are exposed to fuel price volatility when they sign a long-term contract with their customers, they may charge an additional fee associated with fuel costs when prices exceed predetermined levels. Thus, the primary purpose of the fuel surcharge (FSC) revenue is to protect the truck line from fuel price increases during the contract term. III. Planning and Decision Making 121 . . Physical damage insurance. Non-trucking "bobtail Liability Insurance (needed for when the truck is not transporting a crailer). Tolls and scale fees. For an example of a publicly traded transportation company thar primarily uses independent operators, visit Landstar Trucking Company's website at www.nonforced dispatch.com/landstar.php. For a description of a publicly traded transportation company thar primarily owns its rigs and employs company drivers, ste J. B. Hunt Transportation Services' Form 10K ar www.sc. gu/Archresledaar data/728535/000143774914002605/ M/20131231 10kw. Read the discussion in Item 1-Business arrives, drops an empty trailer to replace the trailer just filled, then immediately hooks onto the loaded trailer and departs. Tractor utilization improves because tractors are not sitting idle while a customer loads a trailer. This approach is economically feasible because trailers are far less expensive to purchase and operate than tractors. Most trucking companies keep some tractors "on the fence" as spares, in case one breaks down. There is considerable disagreement, however, over what constitutes too many spares. Some owners believe a truck line should put all available equipment on the road and rent a tractor if a spare is needed. Others disagree and maintain a small number of tractors in reserve. Currently Over-land Trucking Independent contractors generally control their own working hours, unlike an employee. Further, independent contractors' work generally is considered temporary, rather than permanent (unlike for an employee). In the trucking industry, an independent contractor ofren signs a one-year contract for a temporary job. But an employee is hired permanently under the assumption that he or she will make deliveries until further notice. This arrangement constitutes a permanent job. and Freight keeps a small number of tractors and trailers out of service but prepared for duty in case a rig breaks down. Some managers believe this policy is an expensive luxury and that some of these idle rigs could be used to add the new routes requested by FHP. When estimating a tractor's practical capacity, management at Over-land use 85% of total potential miles driven in a period. Theoretical (or 100%) capacity utilization is virtually impossible in the industry because of factors such as traffic and loading delays. CAPACITY ISSUES AND INDUSTRY PRACTICES THE PROPOSAL AND RELATED ISSUES Over-land Trucking typically assigns one driver to one tractor. But this practice can constrain the available hours the tractor can operate. For example, laws require a driver to take a 10-hour break after 11 hours of driving. Further, a driver cannot work more than 70 hours in an eight-day period without taking a 34-hour break. To improve tractor utilization by avoiding constraints based on legal driving time requirements, some trucking companies use "slip seating." This is a practice that permits greater tractor utilization by placing a fresh driver behind the wheel at the end of the former driver's shift. Slip seating is similar in practice to an airline company that keeps its planes flying longer by inserting fresh flight crews as the previous crew goes off duty. It also is efficient to utilize "team drivers" chat are commonly husband-wife teams. One person drives while the other sleeps. Relative to a single driver, this arrangement basically doubles the amount of miles driven in a given week. Typically, teams are paid more, but additional line haul revenues offset the extra labor costs. Another strategy to improve tractor utilization is to use trailer pools, commonly referred to as "drop and hook" systems. For example, trucking companies will leave an empty trailer with customers, who will load it with products as units are produced. When the trailer is filled, a tractor Management at FHP has asked Over-land to consider adding two dry van loads per week; each load would require 1,500 round-trip miles. Because FHP is a long-term client with a strong financial position, the company's management has asked for a very favorable rate of $2.15 per mile including FSC and all miscellaneous fees. Roger believes the potential volume of freight from FHP can be used to grow Over-land's business and profitability. There is also risk associated with not taking the new lines. If Over-land does not accept the new routes, another trucking line will, thus building loyalty with FHP. FHP is a stable, solvent company that presents no question of collection, thus ensuring a reliable cash flow. If FHP decides to restructure its supply chain in the future, Over-land could find itself in the undesirable position of holding dedicated assets (trucks and trailers) for routes that no longer exist. The owner's aversion to increased debt levels further exacerbates concerns about acquiring additional fixed assets. Perhaps Over- land could service the initial demand with existing equipment. But, as additional routes are added in the future, Over-land must acquire more tractor-trailer rigs or consider outsourcing the miles by using independent contractors. Exhibit 1 presents Over-land Trucking and Freight's income from operations for the year ending December 31, 2013. This statement is not prepared in accordance with Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP) but presents costs by behavior. Exhibit 2 presents Over-land Trucking and Freight's balance sheet for the year ending December 31, 2013. Exhibit 2 Over-land Balance Sheet Exhibit 1 Income from Operations (All financial information in the case has been scaled and disguised for educational purposes.) Over-land Trucking and Freight Balance Sheet For the year ending December 31, 2013 Over-land Trucking and Freight Income from Operations For the year ending December 31, 2013 Assets Current Assets Revenue Cash $200,000 300.000 Line Haul Fuel Surcharge Miscellaneous Total Revenue FYE 12/31/2013 $20.925,280 4,950,160 450.120 $26,325,560 Per Mile $1.86 0.44 0.04 $2.34 Accounts Receivable Total $500,000 Variable Expenses Insurance Property Plant and Equipment Land Buildings Accumulated Depreciation Buildings Tractors, Trailers, and Equipment Accumulated Depreciation 1,000,000 3,000,000 (1,250,000 18,650,000 (4.750,000 Total 675,120 8,775,190 112,700 112,550 787,630 4,950,160 255.120 15,668,470 Fuel Oil Lubricants Tolls Parts and Small Tools Hourly Wages: Drivers Trailer Pool Expense Total Variable $16.650.000 Total Assets $17,150,000 Liabilities and Equity Current Liabilities Trailer Pool Expense Total Variable 255.120 15,668,470 Liabilities and Equity Current Liabilities Accounts Payable Taxes Payable Current Portion of Long-Term Debt Total Current Liabilities 150,000 65,000 35.000 $250,000 1,865,000 $1.865.000 $2,115,000 Fixed Expenses Insurance General Liability Physical Damage Workers Compensation Health Insurance Security Depreciation Salaries, Benefits (Garage) Salaries, Benefits (Office) Bad Debt Expense Permits Rental Equipment Payroll Taxes Accounting Fees, Supplies, Computer Maintenance Miscellaneous Total Fixed 112,620 225,010 226,000 224,500 111,750 2,137,500 675,000 1,012,520 113,500 111,520 1,013,000 562,500 112,350 Long-Term Liabilities Notes Payable Total Long-Term Liabilities Total Liabilities Owner's Equity Contributed Capital Retained Earnings Total Owner's Equity 3,550,000 11.485.000 $15,035,000 Total Liabilities and Owner's Equity $17,150,000 337.510 6,975,280 Income from Operations $3,681,810 Note: Per mille values are based on 11.250.000 miles and have been rounded to two decimal places ABSTRACT Over-land Trucking and Freight has a long-established and mutually beneficial business relationship with a major international automotive parts company, FHP Technologies. Management at FHP has approached Over-land with a request to provide additional routes that are important to the efficiency of its supply chain. Over-land's management wishes to nurture the business relationship with FHP but is concerned about the available capacity to service the new routes, potential risks, and profitability associated with FHP's request. INTRODUCTION Alan James founded Over-land Trucking and Freight in 1968 and has grown the business into a sizeable operation with 90 trucks and 180 trailers. His largest customer, FHP Technologies, has submitted a proposal to him to add delivery routes that would improve the efficiency of FHP's supply chain. Alan was not certain that Over-land could handle the additional routes since the company currently was operating at (or near) full capacity. FHP offered a total of $2.15 per mile (including fuel service charge and miscellaneous fees) for the new route. But Alan knew that to accept the offer he would have to add more trucks and perhaps incur additional debt. The question was whether the rates offered by FHP were high enough to offset the associated risks of growing the fleet. Although the business had been grown organically through the years by reinvesting profits, it incurred debt from time to time to replace older equipment (usually in blocks of five trucks). Alan knew the slim profit margins associated with trucking, coupled with a downturn in the economy, could spell disaster if saddled with too much debt. See Exhibits 1 and 2 for the company's most recent statement of income from operations and the balance sheet, respectively. Roger Simmons, Over-land's operations manager for the past 16 years, had been reviewing the FHP proposal and approached Alan. "Alan, we need to discuss this offer from FHP. I think it is a great opportunity for our company, and we need to find a way to make it work." Within 10 minutes Alan and Roger were in a closed-door meeting discussing the pros and cons of FHP's offer. Roger began by stating the obvious: "Alan, this is a huge opportunity for us to grow the business. Not to mention, as FHP becomes more dependent on our services, we will be in a stronger position to negotiate future rate increases. I know you are opposed to debt, and I understand the risks of carrying more debt, but there is more than one way to grow our fleet. If you would consider using independent contract drivers, we could grow the fleet enough to accept FHP's offer without incurring more debt." Alan cringed at the thought of using independent contract drivers. Although independent contractors owned their own trucks, Alan viewed them as difficult to deal with and not worth the headache. "Roger, I hear you, but this new route will not last a week if we cannot give FHP great service. Independent contractors call the shots, not us. They own the rig and will sit at home if they want to. I would rather deal with our own company's rigs and drivers. The rewards just do not justify the risks of damaging our relationship with FHP. Included in miscellaneous revenue are the following: Storage fees are collected when Over-land stores a loaded trailer on its lot for a customer. Lumper revenue is collected if a driver assists with unloading a trailer. "But I am not sure we should take on any more debt at this point to purchase additional rigs. The economy is in the tank, and it is a bad time for us to leverage the balance sheet any further. Roger, my success in this business was not built by jumping on every offer that came along. Sometimes you have to say no, even to your biggest customer. Unless you can find a way to squeeze out more capacity within our current fleet, I just do not think we can accept FHP's offer at this time," Alan concluded. As the two men left the room, Roger was convinced that Alan was wrong. Roger knew that Alan was leaving money on the table. He just needed to prepare a financial analysis that would prove it. Was it possible to squeeze out more capacity from an already fully utilized fleet? Perhaps they could shift trucks from another account. Was taking on more debt truly "risky" given the profit potential of this new route? Roger knew he had to make a convincing argument before FHP took its offer to another truck line. Certain flatbed loads, such as drywall, unpainted steel, and some types of wood products, that would be damaged by rain must be covered. Trucking companies typically charge a tarping fee for such loads. Additional insurance is required when transporting high- value cargo. Practices vary throughout the industry. If a load is above a company's standard cargo insurance limits, many companies simply will not haul it. Trucking companies that are willing to bind additional cargo coverage normally do so for a fee that covers only the extra cost of insurance. (Alternatively, this revenue line item could have been booked as a reduction to the "Insurance" expense account.) INDUSTRY TERMS Loads transported on flatbed trailers must be secured by straps or chains. These types of loads often are associated with higher worker's comp claims. Thus an extra strapping and chaining fee is charged only for a flatbed load. A tractor-trailer rig is a truck that consists of a tractor attached to a trailer. The tractor typically is powered by a diesel engine. A flatbed trailer is long flat platform with no sides. A dry van trailer is a boxed cargo compartment designed for nonrefrigerated freight. Trucking companies often have a revenue-generating load in one direction but need a revenue-generating contract for the return trip. The return trip is known as a backhaul. Often trucking companies contract with freight brokers to acquire backhauls. If a truck sits idle at the dock for more than two hours, customers can be charged a fee that is classified as detention revenue. Placing a detention revenue clause in the contract encourages customers to load trailers efficiently in order to avoid further constraints on Over-land's tractor capacity. TYPES OF BUSINESS ARRANGEMENTS WITH DRIVERS Over-land has potentially two arrangements with drivers. "They are classified as emplosagar as independent operare INDUSTRY BACKGROUND AND COST STRUCTURE Trucking firms generate a variety of revenue types from hauling goods for their clients. Presented next is a brief overview of key types of revenues included in the 2013 income from operations of Over-land Trucking and Freight. Line haul revenue is earned from hauling freight They are classified as employees or as independent operators. Employees receive traditional employee benefits and a Form W2 for tax purposes. These persons are typically engaged in work for the company that is considered "permanent." Alternatively, independent operators are not considered employees and receive a Form 1099 (rather than a Form W2) for tax purposes. These operators typically provide the tractor but generally do not provide the trailer. In addition to driver salaries and depreciation on trucks, expenses incurred by independent contractors include: Tags (known as International Registration Plan (IRP)) - The independent contractor buys the IRP tag for the tractor, while the shipping company buys the tags for the trailer. IRS Form 2290 - Heavy Road Use Tax. Diesel fuel, engine fluids, and all maintenance-related parts and items. Fuel prices in recent years have been volatile. Because trucking companies are exposed to fuel price volatility when they sign a long-term contract with their customers, they may charge an additional fee associated with fuel costs when prices exceed predetermined levels. Thus, the primary purpose of the fuel surcharge (FSC) revenue is to protect the truck line from fuel price increases during the contract term. III. Planning and Decision Making 121 . . Physical damage insurance. Non-trucking "bobtail Liability Insurance (needed for when the truck is not transporting a crailer). Tolls and scale fees. For an example of a publicly traded transportation company thar primarily uses independent operators, visit Landstar Trucking Company's website at www.nonforced dispatch.com/landstar.php. For a description of a publicly traded transportation company thar primarily owns its rigs and employs company drivers, ste J. B. Hunt Transportation Services' Form 10K ar www.sc. gu/Archresledaar data/728535/000143774914002605/ M/20131231 10kw. Read the discussion in Item 1-Business arrives, drops an empty trailer to replace the trailer just filled, then immediately hooks onto the loaded trailer and departs. Tractor utilization improves because tractors are not sitting idle while a customer loads a trailer. This approach is economically feasible because trailers are far less expensive to purchase and operate than tractors. Most trucking companies keep some tractors "on the fence" as spares, in case one breaks down. There is considerable disagreement, however, over what constitutes too many spares. Some owners believe a truck line should put all available equipment on the road and rent a tractor if a spare is needed. Others disagree and maintain a small number of tractors in reserve. Currently Over-land Trucking Independent contractors generally control their own working hours, unlike an employee. Further, independent contractors' work generally is considered temporary, rather than permanent (unlike for an employee). In the trucking industry, an independent contractor ofren signs a one-year contract for a temporary job. But an employee is hired permanently under the assumption that he or she will make deliveries until further notice. This arrangement constitutes a permanent job. and Freight keeps a small number of tractors and trailers out of service but prepared for duty in case a rig breaks down. Some managers believe this policy is an expensive luxury and that some of these idle rigs could be used to add the new routes requested by FHP. When estimating a tractor's practical capacity, management at Over-land use 85% of total potential miles driven in a period. Theoretical (or 100%) capacity utilization is virtually impossible in the industry because of factors such as traffic and loading delays. CAPACITY ISSUES AND INDUSTRY PRACTICES THE PROPOSAL AND RELATED ISSUES Over-land Trucking typically assigns one driver to one tractor. But this practice can constrain the available hours the tractor can operate. For example, laws require a driver to take a 10-hour break after 11 hours of driving. Further, a driver cannot work more than 70 hours in an eight-day period without taking a 34-hour break. To improve tractor utilization by avoiding constraints based on legal driving time requirements, some trucking companies use "slip seating." This is a practice that permits greater tractor utilization by placing a fresh driver behind the wheel at the end of the former driver's shift. Slip seating is similar in practice to an airline company that keeps its planes flying longer by inserting fresh flight crews as the previous crew goes off duty. It also is efficient to utilize "team drivers" chat are commonly husband-wife teams. One person drives while the other sleeps. Relative to a single driver, this arrangement basically doubles the amount of miles driven in a given week. Typically, teams are paid more, but additional line haul revenues offset the extra labor costs. Another strategy to improve tractor utilization is to use trailer pools, commonly referred to as "drop and hook" systems. For example, trucking companies will leave an empty trailer with customers, who will load it with products as units are produced. When the trailer is filled, a tractor Management at FHP has asked Over-land to consider adding two dry van loads per week; each load would require 1,500 round-trip miles. Because FHP is a long-term client with a strong financial position, the company's management has asked for a very favorable rate of $2.15 per mile including FSC and all miscellaneous fees. Roger believes the potential volume of freight from FHP can be used to grow Over-land's business and profitability. There is also risk associated with not taking the new lines. If Over-land does not accept the new routes, another trucking line will, thus building loyalty with FHP. FHP is a stable, solvent company that presents no question of collection, thus ensuring a reliable cash flow. If FHP decides to restructure its supply chain in the future, Over-land could find itself in the undesirable position of holding dedicated assets (trucks and trailers) for routes that no longer exist. The owner's aversion to increased debt levels further exacerbates concerns about acquiring additional fixed assets. Perhaps Over- land could service the initial demand with existing equipment. But, as additional routes are added in the future, Over-land must acquire more tractor-trailer rigs or consider outsourcing the miles by using independent contractors. Exhibit 1 presents Over-land Trucking and Freight's income from operations for the year ending December 31, 2013. This statement is not prepared in accordance with Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP) but presents costs by behavior. Exhibit 2 presents Over-land Trucking and Freight's balance sheet for the year ending December 31, 2013. Exhibit 2 Over-land Balance Sheet Exhibit 1 Income from Operations (All financial information in the case has been scaled and disguised for educational purposes.) Over-land Trucking and Freight Balance Sheet For the year ending December 31, 2013 Over-land Trucking and Freight Income from Operations For the year ending December 31, 2013 Assets Current Assets Revenue Cash $200,000 300.000 Line Haul Fuel Surcharge Miscellaneous Total Revenue FYE 12/31/2013 $20.925,280 4,950,160 450.120 $26,325,560 Per Mile $1.86 0.44 0.04 $2.34 Accounts Receivable Total $500,000 Variable Expenses Insurance Property Plant and Equipment Land Buildings Accumulated Depreciation Buildings Tractors, Trailers, and Equipment Accumulated Depreciation 1,000,000 3,000,000 (1,250,000 18,650,000 (4.750,000 Total 675,120 8,775,190 112,700 112,550 787,630 4,950,160 255.120 15,668,470 Fuel Oil Lubricants Tolls Parts and Small Tools Hourly Wages: Drivers Trailer Pool Expense Total Variable $16.650.000 Total Assets $17,150,000 Liabilities and Equity Current Liabilities Trailer Pool Expense Total Variable 255.120 15,668,470 Liabilities and Equity Current Liabilities Accounts Payable Taxes Payable Current Portion of Long-Term Debt Total Current Liabilities 150,000 65,000 35.000 $250,000 1,865,000 $1.865.000 $2,115,000 Fixed Expenses Insurance General Liability Physical Damage Workers Compensation Health Insurance Security Depreciation Salaries, Benefits (Garage) Salaries, Benefits (Office) Bad Debt Expense Permits Rental Equipment Payroll Taxes Accounting Fees, Supplies, Computer Maintenance Miscellaneous Total Fixed 112,620 225,010 226,000 224,500 111,750 2,137,500 675,000 1,012,520 113,500 111,520 1,013,000 562,500 112,350 Long-Term Liabilities Notes Payable Total Long-Term Liabilities Total Liabilities Owner's Equity Contributed Capital Retained Earnings Total Owner's Equity 3,550,000 11.485.000 $15,035,000 Total Liabilities and Owner's Equity $17,150,000 337.510 6,975,280 Income from Operations $3,681,810 Note: Per mille values are based on 11.250.000 miles and have been rounded to two decimal places

Step by Step Solution

There are 3 Steps involved in it

Get step-by-step solutions from verified subject matter experts