1..Based on the facts presented in the case study, should Richard Grasso, have been compelled tore turn what was considered by many to be "excessive compensation"? Why or why not?

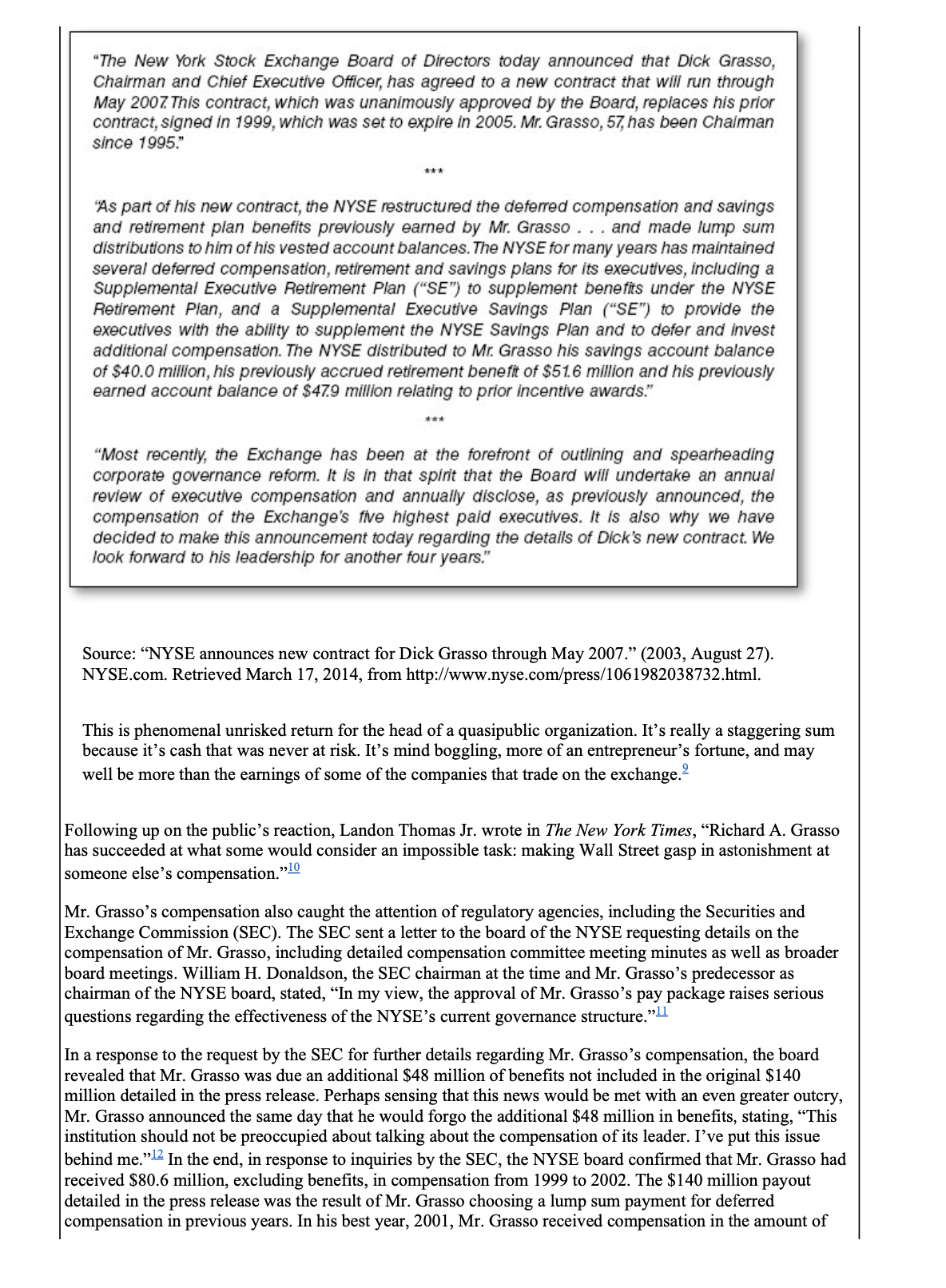

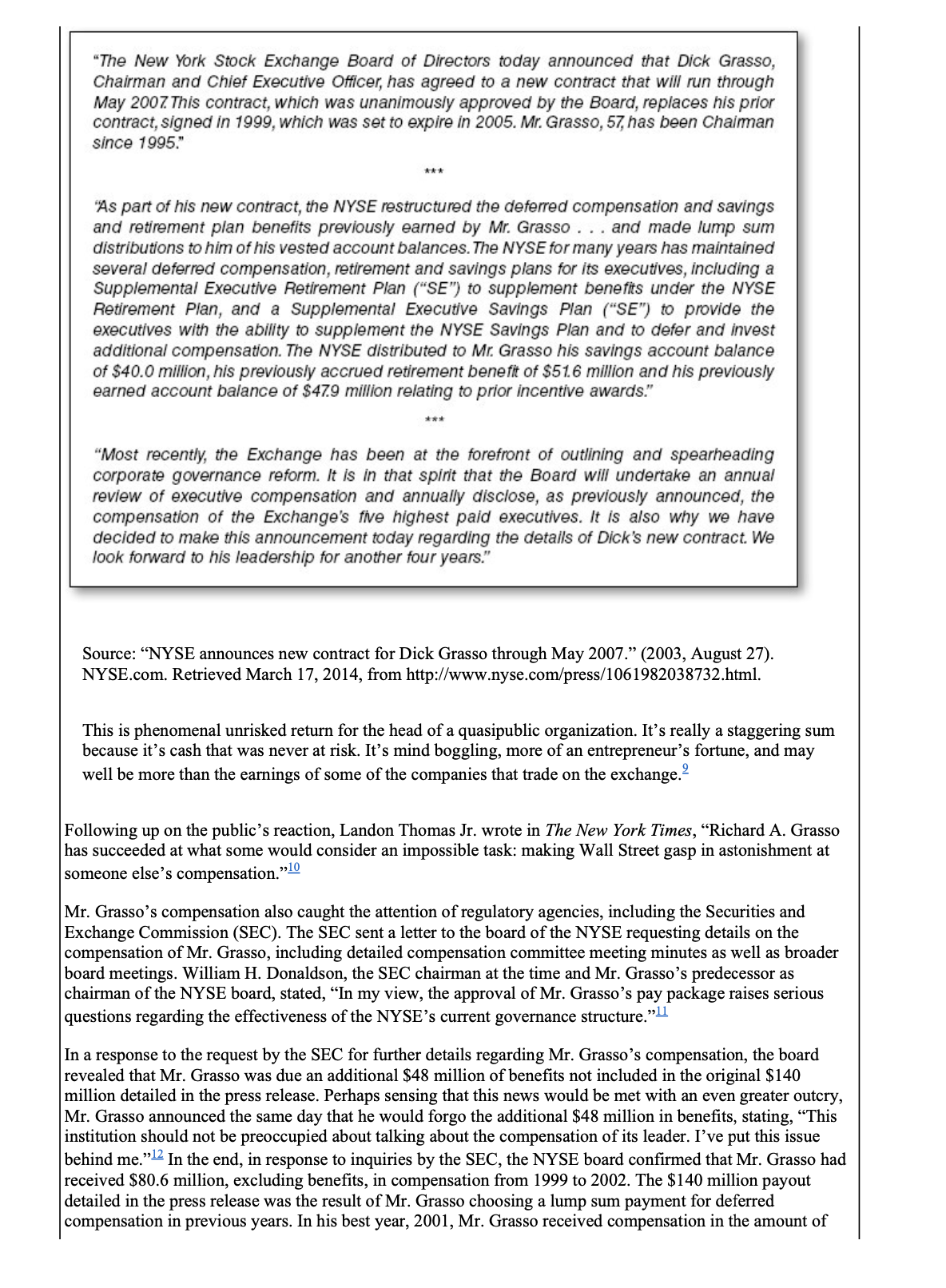

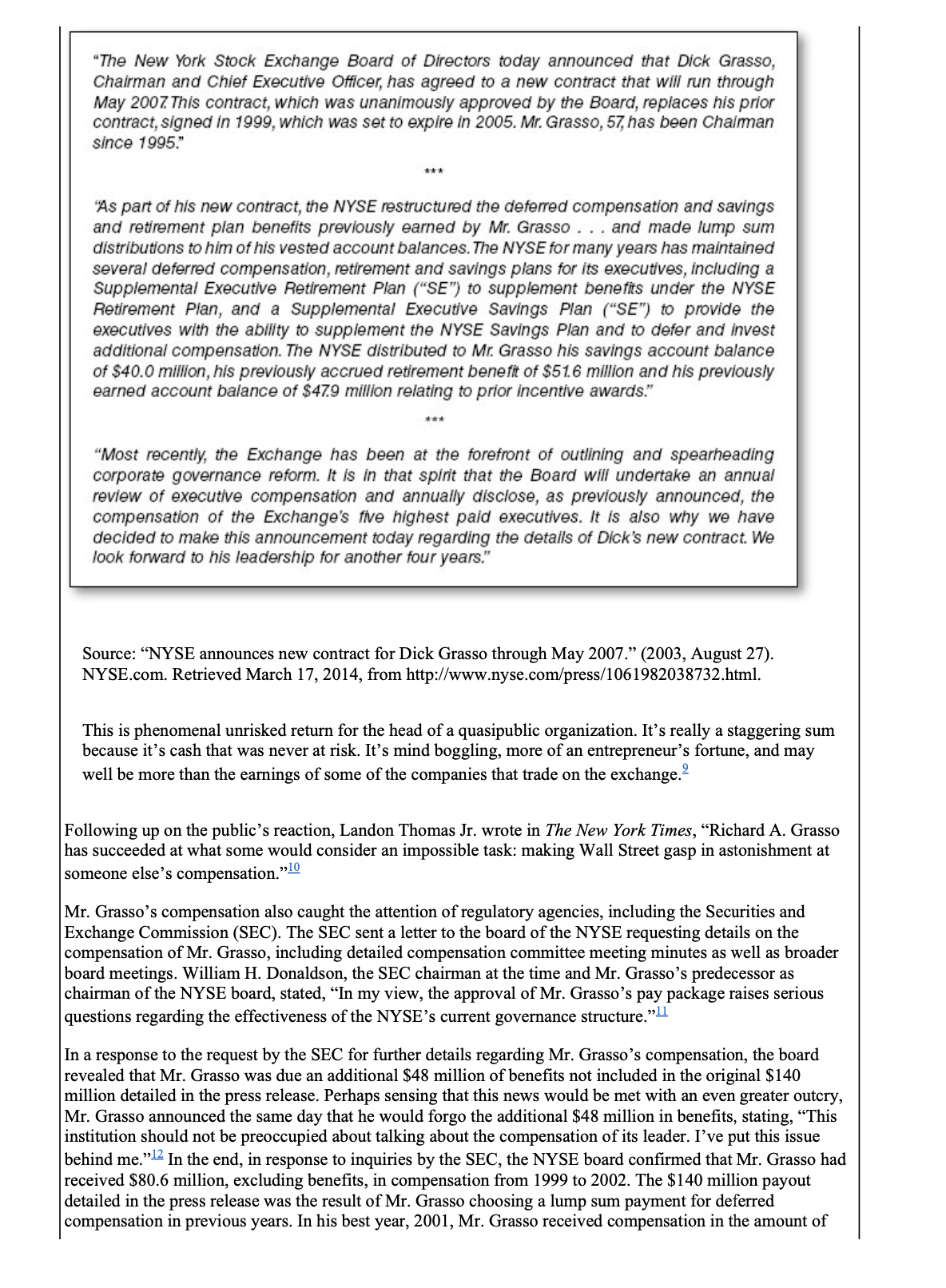

The New York Stock Exchange and Richard Grasso: Excessive Compensation as a Failure of Corporate Governance You can't pay the head of a not-for-profit that much money. The amount paid, close to $200 million US.... It's not reasonable. -Eliot Spitzer, former New York State attorney general- These were honest, diligent, and sound compensation decisions that were thoroughly researched and, most importantly, supported by 100 percent of the board. Statement from Kenneth Langone, former NYSE director and chair of the compensation committee- Those who thought they could break me... badly underestimated my character and resolve. -Richard Grasso, former chairman and CEO of the New York Stock Exchange"Our systems are all go. At 9:30 Monday morning trading will resume on both markets, and the message will be given to the criminals who foisted this on America that they lost," stated Richard Grasso upon announcing the reopening of the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE) after the terrorist attacks on September 11." Trading on the NYSE had been canceled that fateful Tuesday after the second plane crashed into the South Tower, and the Exchange had remained closed for the remainder of the week after the September 1 1 attacks. In the wake of the tragedy, Mr. Grasso became the public face of the Exchange and was widely praised for enabling the Exchange to return to operations in such a short time, even amid the devastation of lower Manhattan. Rudy Giuliani, the mayor of New York City at the time of the attacks, lauded Mr. Grasso as a hero for his role in reopening the Exchange. Roberta Karmel, a former NYSE director, stated to The New York Times, "After 9/1 1 people couldn't say enough about him." Yet, just two years after being praised as a hero, Mr. Grasso was asked to step down as the chairman and chief executive officer of the Exchange. How did Mr. Grasso fall so quickly and so hard from an American hero extolled for his leadership to a tarnished executive denigrated as a symbol of corporate greed and crony capitalism? The answer to this question involves the ongoing business debate on the scale of executive pay, the appropriate board composition to ensure effective corporate governance, and the controversial dual role of CEO and chairman. The New York Stock Exchange The New York Stock Exchange (NYSE) was at the time an iconic landmark of not only the United States but also the global financial system. In a piece titled "Fixing a Tarnished Market," The New York Times stated, 'There is no more evocative monument to the vibrancy of American capitalism, and to New York City's claim to be the world's financial capital, than the graceful, colonnaded building that houses the New York Stock Exchange on Wall Street." The NYSE was at the time the world's largest stock-trading exchange, with market capitalization of its listed companies at $14.4 trillion as of December 201 1 and a daily trading volume of $153 million in 2008 The NYSE was founded in 1792 by an agreement between 24 stockbrokers in New York City. In 1817, the institution drafted a new constitution and officially adopted the name "New York Stock & Exchange Board." The Exchange grew over the first half of the 19th century and in 1865 moved to its current street, Broad Street in lower Manhattan. Then, in 1903, the current facade and building was constructed along with a new trading floor. From its founding to December 2005, the NYSE was a quasi-public institution, existing as a nonprofit under New York State law, charged with a vital regulatory role. However, in December 2005, with its merger with electronic trading rival, Archipelago, the NYSE officially became a for-profit company. In March 2006, the NYSE began trading under the name "NYSE Group." Then, in April 2007, NYSE Group merged with Euronext, the European combined stock market, forming the first transatlantic stock exchange, named "NYSE Euronext." Throughout its 220 years of existence, the NYSE faced many trials and challenges, including fires, financial panics, insider trading scandals, and the onset of electronic trading. Despite these challenges, the NYSE endured and remained the symbol of American capitalism. Richard Grasso Richard A. "Dick" Grasso's rise was in many ways the classic Horatio Alger story. Born in Jackson Heights, Queens, New York City in 1946, Mr. Grasso was raised by his mother and two aunts after his father left the family when he was just an infant. After graduating from high school, Mr. Grasso attended Pace University for two years prior to enlisting in the Army. In 1968, after leaving the Army, Mr. Grasso was hired as a clerk for the New York Stock Exchange. Over the next 22 years, Mr. Grasso's rise through the ranks of the New York Stock Exchange would ultimately culminate in his appointment as president in 1988 and chairman in 1995. Mr. Grasso held the positions of chief executive and chairman of the NYSE until his resignation in 2003. Mr. Grasso was widely accredited with establishing the NYSE as the preeminent stock exchange in United States during his leadership tenure. In the press release announcing his new employment contract, the NYSE Board stated:Under Dick's leadership, the NYSE has experienced tremendous growth and success. It has added 1,549 of its 2,300 listed companies, including most of out nearly 500 non-US. companies. During this period the market capitalization of the companies listed on the NYSE has more than doubled to $14.8 trillion. In the process, Dick revolutionized the Exchange's technological platform, making it the most efficient and sophisticated in the industry. The value of a seat on the exchange has nearly tripled during his tenure. And throughout his term, Dick has shown an unwavering commitment to regulation and the interests of America's 85 million investors. From his commitment to technology and innovation, which has made the NYSE the world's most efcient and reliable equities market, to leading the securities industry out of the tragedy of 9111, to his unwavering commitment to investor protection, Dick's leadership has been outstanding.g Yet, this very press release praising Mr. Grasso's outstanding leadership and commitment would result in the compensation scandal that would ultimately end with Mr. Grasso's resignation just one month after its release. Compensation Controversy On August 27, 2003, the board of directors of the New York Stock Exchange circulated a press release detailing the organization's new employment contract with its chairman and chief executive officer, Dick Grasso. This press release was the rst time in the NYSE's ZOO-year history that the Exchange released information regarding the compensation package for its chief executive. What was intended to be an innocuous press release announcing the continued leadership of the Exchange's longtime CEO and chairman in effect resulted in Mr. Grasso resigning as CEO and chairman less than three weeks later. See Exhibit 6.1 for excerpts from the press release. The press release detailed a compensation package that included $140 million in accrued savings and incentives as well as a $1.5 million salary and a guaranteed bonus of at least $1.0 million. Public reaction to the press release and compensation details was swift and harsh. Charles M. Elson, chairman of the corporate g0vernance program at the University of Delaware, stated: Exhibit 6.1 Excerpts From Press Release "The New York Stock Exchange Board of Directors today announced that Dick Grasso, Chairman and Chief Executive Officer, has agreed to a new contract that will run through May 2007 This contract, which was unanimously approved by the Board, replaces his prior contract, signed in 1999, which was set to expire in 2005. Mr. Grasso, 57, has been Chairman since 1995." "As part of his new contract, the NYSE restructured the deferred compensation and savings and retirement plan benefits previously earned by Mr. Grasso . . . and made lump sum distributions to him of his vested account balances. The NYSE for many years has maintained several deferred compensation, retirement and savings plans for its executives, including a Supplemental Executive Retirement Plan ("SE") to supplement benefits under the NYSE Retirement Plan, and a Supplemental Executive Savings Plan ("SE") to provide the executives with the ability to supplement the NYSE Savings Plan and to defer and invest additional compensation. The NYSE distributed to Mr. Grasso his savings account balance of $40.0 million, his previously accrued retirement benefit of $51.6 million and his previously earned account balance of $47.9 million relating to prior incentive awards." "Most recently, the Exchange has been at the forefront of outlining and spearheading corporate governance reform. It is in that spirit that the Board will undertake an annual review of executive compensation and annually disclose, as previously announced, the compensation of the Exchange's five highest paid executives. It is also why we have decided to make this announcement today regarding the details of Dick's new contract. We look forward to his leadership for another four years." Source: "NYSE announces new contract for Dick Grasso through May 2007." (2003, August 27). NYSE.com. Retrieved March 17, 2014, from http://www.nyse.com/press/1061982038732.html. This is phenomenal unrisked return for the head of a quasipublic organization. It's really a staggering sum because it's cash that was never at risk. It's mind boggling, more of an entrepreneur's fortune, and may well be more than the earnings of some of the companies that trade on the exchange. Following up on the public's reaction, Landon Thomas Jr. wrote in The New York Times, "Richard A. Grasso has succeeded at what some would consider an impossible task: making Wall Street gasp in astonishment at someone else's compensation."10 Mr. Grasso's compensation also caught the attention of regulatory agencies, including the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC). The SEC sent a letter to the board of the NYSE requesting details on the compensation of Mr. Grasso, including detailed compensation committee meeting minutes as well as broader board meetings. William H. Donaldson, the SEC chairman at the time and Mr. Grasso's predecessor as chairman of the NYSE board, stated, "In my view, the approval of Mr. Grasso's pay package raises serious questions regarding the effectiveness of the NYSE's current governance structure." In a response to the request by the SEC for further details regarding Mr. Grasso's compensation, the board revealed that Mr. Grasso was due an additional $48 million of benefits not included in the original $140 million detailed in the press release. Perhaps sensing that this news would be met with an even greater outcry, Mr. Grasso announced the same day that he would forgo the additional $48 million in benefits, stating, "This institution should not be preoccupied about talking about the compensation of its leader. I've put this issue behind me." In the end, in response to inquiries by the SEC, the NYSE board confirmed that Mr. Grasso had received $80.6 million, excluding benefits, in compensation from 1999 to 2002. The $140 million payout detailed in the press release was the result of Mr. Grasso choosing a lump sum payment for deferred compensation in previous years. In his best year, 2001, Mr. Grasso received compensation in the amount of$30.5 million, just shy of his company's total reported earnings for that year, $31.8 million. Mr. Grasso was soon met with widespread calls for his immediate resignation. Investors, the SEC, and public officials representing public pension funds in New York and California demanded that Mr. Grasso step down as the leader of the NYSE. After publicly denying his intention to resign for three weeks, on September 17, 2003, Mr. Grasso announced that he would immediately resign from his positions as chairman and chief executive of the NYSE. Upon announcing his resignation, Mr. Grasso stated, "I believe this course is in the best interest of both the exchange and myself." He went on to say that he was resigning "with the deepest reluctance." In fact, Mr. Grasso was not alone in his reluctance regarding his resignation. Seven of the 20 board members of the NYSE voted against accepting Mr. Grasso's resignation. Other observers were wary of the implications to corporate governance caused by the forced resignation of a successful executive simply as a result of negative public and regulatory reaction to compensation. Jeffrey Sonnenfeld, at the time an associate dean of the Yale School of Management, commented, "This will be the first time in American history where someone who is said to have done a good job is being fired because the board is paying him too much. The board's accountability is the second issue to be dealt with." Indeed, Mr. Grasso's resignation did not end the controversy or the scrutiny of the NYSE's board. Following Mr. Grasso's resignation, additional executives and board members involved in the compensation scandal also resigned or retired, including Frank Ashen, a 25-year veteran of the Exchange; Jurgen Schrempp, chief executive of DaimlerChrysler; and H. Carl Mccall, a former politician who as chairman of the Exchange's compensation committee signed Mr. Grasso's contract extension that extended $48 million of additional benefits on top of the $140 million. Less than a year after his resignation, in May 2004, Mr. Grasso was sued by New York State, demanding repayment of $100 million of his $140 million compensation package. Eliot Spitzer, New York State's attorney general at the time, filed the complaint against Mr. Grasso with the New York State Supreme Court, stating, "There is a simple reality here. Mr. Grasso was paid too much. He has the money in his checking account and he has an obligation to return it." The complaint against Mr. Grasso alleged that Mr. Grasso inflated his pay and intentionally manipulated his board to approve a compensation package that far exceeded the benchmark for comparable executives. Additionally, Mr. Spitzer had convinced Frank Ashen, the NYSE's internal compensation director and a longtime co-employee with Mr. Grasso, to provide testimony that Mr. Grasso hid $18 million in bonus compensation from the board. Mr. Ashen, who was initially to be named in the lawsuit, agreed to pay back $1.3 million in compensation and provide testimony. The lawsuit painted a picture of a symbiotic relationship between Mr. Grasso and his board, including Mr. Grasso overlooking conflicts of interest for Wall Street research analysts when executives from those firms were authorizing his compensation. In response to the lawsuit, Mr. Grasso stated that he would not repay any of his compensation, commenting, "I'm disappointed that New York's attorney general has chosen to intervene in what amounts to be a commercial dispute between my former employer and me. I look forward to a complete vindication in court." Mr. Grasso filed a countersuit against NYSE and its new chairman, John Reed, claiming "defamation of character." The lawsuits, which would not be fully settled until two years later, placed questions on the scale of executive pay, board composition, and the dual role of CEO and chairman at the forefront of media attention and business debate. Board Composition According to the investigative report completed by Winston & Strawan on behalf of the NYSE published on December 15, 2003, Mr. Grasso "had a strong influence in who was selected as members of the Nominating Committee and the Board, and he personally selected which Board members served on the Compensation Committee." This committee was the committee responsible for approving Mr. Grasso's annual compensation. In the wake of the corporate scandals, a renewed interest was placed on the CEO's relationship with the board and the growing trend of an interlocking directorate in the United States: the practice of directors sitting on multiple boards of various companies in different industries.Dual Role of CEO and Chairman At the time of the compensation scandal, Mr. Grasso was both the chief executive and chairman of the board of the NYSE. When a chief executive ofcer also holds the position of chairman of the board, it is commonly referred to as \"CEO duality.\" The effects of CEO duality on the efcacy of boards and rm nancial performance have long been debated and studied. The landmark report on corporate governance issued by the Cadbury Commission in 1992, now referred to as the Cadbury Report, recommended that the CEO and chairman roles be separated to ensure effective corporate governance. Specically, the report dictated as follows: Given the importance and particular nature of the chairman's role, it should in principle be separate from that of the chief executive. If the two roles are combined in one person, it represents a considerable concentration of power. We recommend, therefore, that there should be a clearly accepted division of responsibilities at the head of the company, which will ensure a balance of power and authority, such that no one individual has unfettered powers of decision. Where the chairman is also the chief executive, it is essential that there should be a strong and independent element on the board.E Despite this clear recommendation, CEO duality remained commonplace in the United States through the early 2000s. The high-prole corporate scandals of the early 2000s gave birth to renewed focus on ensuring that two separate individuals hold the two most powerful positions within a company. As of 201 2, there was no specic law or regulation requiring publicly traded companies to separate the chairman and CEO roles, though many shareholders and investors vocalized a preference for separation. An Ongoing Debate The New York State lawsuit and Mr. Grasso's lawsuits moved to trial two years after their initial lings. On October 19, 2006, a New York judge ruled that Mr. Grasso must return a large portion of his compensation. The judge found that Mr. Grasso had deceived his board on details pertaining to his compensation, preventing the board 'om performing its duciary responsibilities, and that he had gained access to retirement funds prematurely. The judge stopped short of stating that Mr. Grasso had committed any illegal activities. The order that Mr. Grasso return millions in compensation was called \"the shot heard round the boardrooms\" by New York Times journalist Gretchen Morgenson. Writing in The New York Times, Morgenson wrote, \"The days of pouring other people's money into the pockets of CEO's without justication are over.\"a At the time of the judgment, Mr. Grasso's suit claiming defamation was also dismissed. Mr. Grasso vowed to appeal the decisions, and the legal ght moved to the New York State Court of Appeals. In the appeal, Mr. Grasso's attorney's argued that the judge had \"ignored the law and the facts.\"2 On July 1, 2008, the New York State Court of Appeals ruled that Mr. Grasso was entitled to keep his compensation and dismissed all outstanding claims against him. The majority decision cited the fact that NYSE was now a division of a for-prot corporation and that New York had no oversight authority on issues of compensation, ultimately stating that further matters were \"not in the public interest.\" The decision also dismissed outstanding claims Mr. Grasso had against New York and the Exchange. In response to the decision, Mr. Grasso stated, \"Right now I'm going to turn to my family and we're going to move on to the M chapter.\" The Grasso compensation controveISy lasted for more than ve years, providing fuel for a national debate on executive compensation, board composition, and the dual role of CEO/chairman. The debate was still ongoing in 2012, and the Grasso controversy was still being referenced as an example of excessive CEO compensation. Sanjay Sangohoee wrote for Fortune magazine, in his article titled \"We're Having the Wrong Debate on CEO Pay\": The other big weakness in our system is the propensity of companies and shareholders to accept the \"divine right" of CEOs, which elevates them to monarch status and enables them to run their companies like private kingdoms rather than as trusts run for the sake of the owners. Nowhere was this phenomenon more clearly evident than in the case of Dick Grasso, the former head of the New York Stock Exchange, whose disproportionately large $190 million pay package became possible due at least in part to his personally handpicked board, absolute stranglehold ever the NYSE's activities, as well as his ability to regulate the very people who were tasked with deciding his compensation.a In many ways, the sentiment expressed by The New York Times just days after the now infamous NYSE press release in 2003 captured the essence of the ongoing debate on corporate governance and executive compensation nearly a decade after the start of the Grasso controversy. The New York Times stated: The recent corporate scandals have taught us, if nothing else, that when reckless chief executives are able to raid their institutions' treasuries at will and enrich themselves beyond reason, it's a sure sign that corporate governance has been corrupted to an alarming degree.g The question remains: Has corporate governance evolved since 2003, or are there still unresolved deciencies in US. corporate governance practices, specically regarding executive compensation