Question

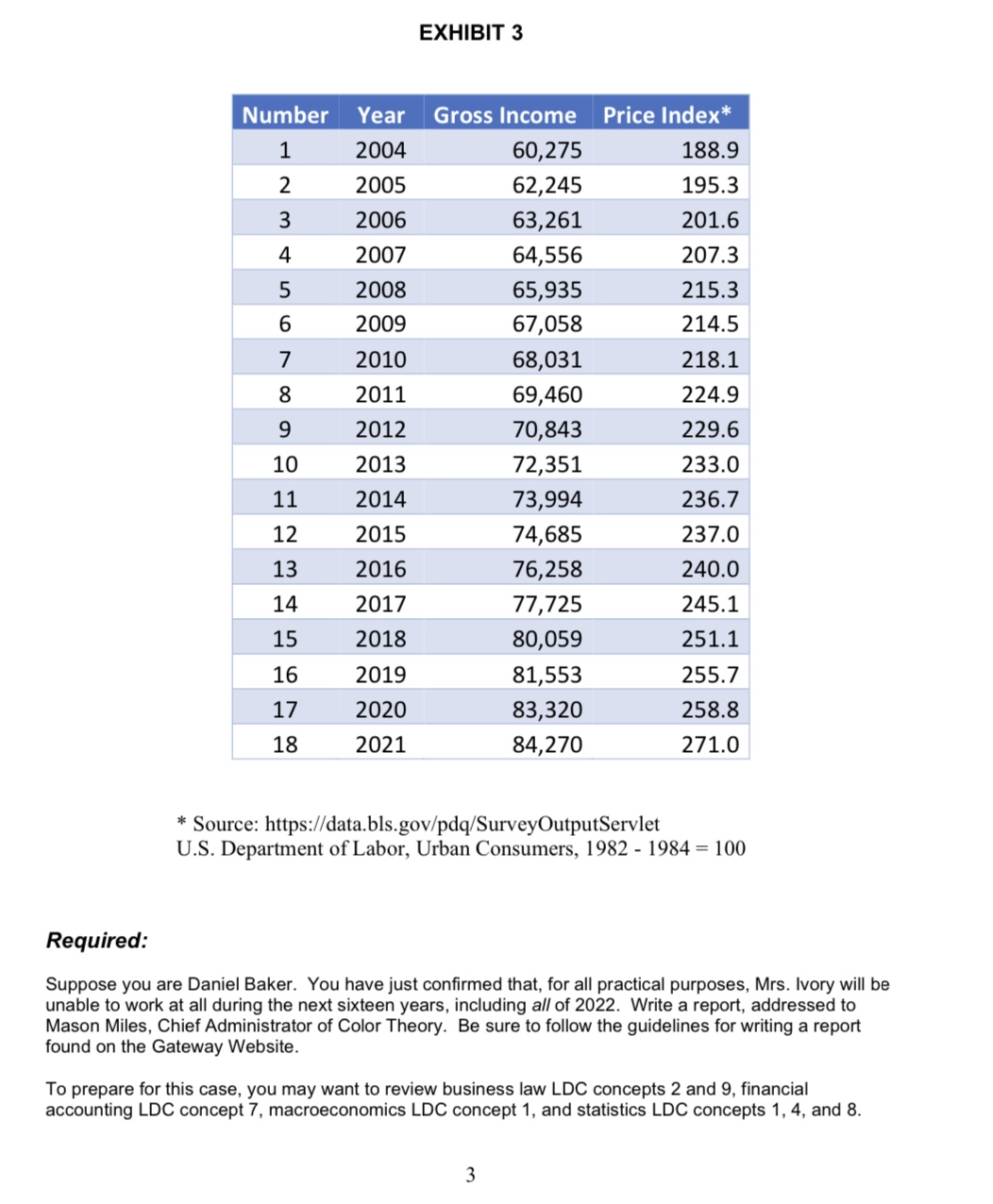

3. Assume that Mrs. Ivorys real income will not change over the next sixteen years. Use the mean real income from question 1 to determine

3. Assume that Mrs. Ivorys real income will not change over the next sixteen years. Use the mean real income from question 1 to determine projected real income for the future sixteen years of Mrs. Ivorys work expectancy. Use the regression equation from question 2 to project adjusted price indices for the next sixteen years. Assume that Mrs. Ivory pays 20% of her actual income in taxes and that Green will not provide significant state assistance. Use the projected real income and adjusted price indices to estimate Mrs. Ivorys net actual income for the next sixteen years. What would be the likely amount of an award to Mrs. Ivory based on a present value rate of 8%? Discuss the factors that could cause Mrs. Ivorys future income to differ from your estimate.

-what if economy changes

-think of other povwhat will make my estimates excessive.

Daniel Baker, Customer Relations Manager, for Color Theory, was in a quandary. He pondered over a memo from James Power, Loss Prevention Manager at Color Theory, (Exhibit 1) and a letter addressed to him from Megan Ivory, a customer, (Exhibit 2). What appeared to have been a routine shoplifting incident on the part of Mrs. Ivory turned out to lack evidence. To make matters worse, the suspect was injured during apprehension. It appeared that Color Theory faced the possibility of a lawsuit because of the incident. Mason Miles, the Chief Administrator, had asked Mr. Baker to assess the legal and financial consequences of the case, make recommendations, and report back to him. Color Theory is a large stationery and drawing supplies retailer with approximately 50 stores located throughout the State of Green. The firm has been established for many years, making steady, if unspectacular profits. EXHIBIT 1 MEMORA N D UM DATE: TO: FROM: SUBJECT: January 3,2022 File James Power, Loss Prevention Manager Shoplifting Incident At 1:50 p.m. today, I observed a customer, Megan Ivory, who was standing next to calligraphy sets in the store, make a sudden move to her pocket. She then proceeded at an accelerated pace toward the exit. I noticed that her side pocket was stuffed. I then proceeded directly to where the customer had been standing and noticed that a calligraphy pen set was missing. It so happened that I noticed earlier that day that the calligraphy pen sets were fully stocked up. I assumed that the customer, who I had previously observed, had shoplifted the set. As the customer was about to leave the store by then, I began chasing after her and reached her at the store's entrance. Fearing that I might lose her in the crowd, I shouted at her to stop. I then grasped her by the arm and shoved her back to the store. Apparently, the customer lost her balance and fell on her back hitting one of the checkout counters. She seemed to be hurt a little, but then I offered to help her stand up, although she continued to limp. I then asked her if she had forgotten to pay for something. She seemed surprised and said that she does not understand what I am talking about. I then directed her to follow me to the Loss Prevention room. Diana Rhead, one of the checkout employees, helped her walk toward the Loss Prevention room as the customer complained she was having difficulty walking and was experiencing terrible back pain. I closely walked behind the two of them. Per the store's protocol, I then advised the customer that she would have to wait until the store's manager came back from a meeting for the investigation to begin. The store's manager, Sandra Brooks, was due to return from a meeting at 2:15 p.m. that day. Unfortunately, she only returned at 3:15 p.m. At that time, Mrs. Brooks advised the customer why she was being held up and asked her to empty her pockets. However, no calligraphy set was found. Mrs. Brooks then apologized for the inconvenience, gave her a $30 gift certificate, and wished the customer well. I really did not mean to hurt the customer, but apparently, her fall did some damage to her as she kept complaining that her back hurts. EXHIBIT 2 Megan Ivory 88 Blue Street Orange City, Green February 18,2022 Mason Miles, Chief Administrator Color Theory 33 Navy Blvd. Peach City, Green Re: incident dated January 3rd,2022 Dear Mr. Miles: Based on permanent injuries inflicted on me by one of your employees while falsely imprisoning me on January 3rd, 2022 , I demand compensation in the sum of $665,000 in medical care expenses and $700,000 for the loss of future income. On January 3rd,2022, I came to your store to locate some art supplies for my daughter's art project at school. While I was examining a number of calligraphy sets that you had on the shelves, I was not able to find the calligraphy set my daughter's teacher requested. Rushed to make it back to an appointment I had with a client that afternoon, I headed toward the store's exit. As I was about to leave the store's premises, I heard someone shout behind me ordering me to stop immediately while using some foul language. When I looked back, I saw a six-foot, two-hundred-pound man grabbing my arm and shoving me back to the store. Due to the tremendous force of that shoving, I lost balance and fell on my back, right against one of the store's checkout counters. I immediately felt extreme pain in my back and was unable to move. I was then helped out by a store employee and was ordered to go to the Loss Prevention room. I was told that police would be called to the premises if I did not directly go to the Loss Prevention room. There were approximately twenty-five customers watching me as I was escorted to the Loss Prevention room. I felt extremely embarrassed by the ordeal. Once we got to the Loss Prevention room, I asked the man, who accosted me at the store's entrance and who then followed me to the room, the reason for my detention. He then mentioned that it is against the store's policy for him to discuss the matter further and that I would have to wait for the store's manager. Almost an hour later, the store manager, Mrs. Brooks, arrived. At that point, she notified me that I have been detained because one of the store's employees had observed me stealing a calligraphy pen set. I immediately denied any involvement in the matter and offered to empty my pockets. Mrs. Brooks was then satisfied that I had done nothing wrong. She politely apologized and allowed me to leave the store's premises. Later that afternoon, I was admitted to Cedars Sinai Hospital emergency room as I was experiencing severe back pain arising out of my fall earlier that day. That same night, a team of surgeons operated on my back as the condition severely deteriorated. However, they were unable to successfully treat the back injuries in this and in two other surgeries that followed. I am now diagnosed with an abnormal degeneration of my spine resulting in irreparable back injury and permanent disability. This condition prevents me from ever walking again or from ever sitting down for more than ten minutes at a time. As a result of this permanent condition, I had to quit my job as a regional salesperson for Purple Care, a pharmaceutical company. My doctor's diagnosis indicates that these injuries to my back would prevent me from ever working again. Besides my past and future medical bills, I am also demanding that you compensate me for the loss of future income. As a forty-nine years old, highly successful career woman in the field of pharmaceutical sales, I am now deprived of any prospects of employment for the rest of my life. I am attaching a copy of my gross yearly income from my sales position during the last eighteen years. (See Exhibit 3). Please respond to my settlement offer on or before April 15. I hope this matter could be resolved amicably. Sincerely, Megan Ivory Enclosures EXHIBIT 3 * Source: https://data.bls.gov/pdq/SurveyOutputServlet U.S. Department of Labor, Urban Consumers, 19821984=100 Required: Suppose you are Daniel Baker. You have just confirmed that, for all practical purposes, Mrs. Ivory will be unable to work at all during the next sixteen years, including all of 2022. Write a report, addressed to Mason Miles, Chief Administrator of Color Theory. Be sure to follow the guidelines for writing a report found on the Gateway Website. To prepare for this case, you may want to review business law LDC concepts 2 and 9 , financial accounting LDC concept 7 , macroeconomics LDC concept 1 , and statistics LDC concepts 1,4 , and 8. COLOR THEORY LIBRARY PAUL CALDWELL, PLAINTIFFRESPONDENT, v. TODD KHLER DEFENDANT-APPELLANT A-108 September Term 1993 Supreme Court of Green March 14, 1994, Argued July 6, 1994, Decided PRIOR HISTORY: [**1] COUNSEL: W. Stephen Leary argued the cause for appellant. Raymond T. Roche argued the cause for respondent OPINIONBY: HANDLER OPINION: On May 21, 1987, Todd Khler (hereinafter defendant), who was operating a car struck the rear end of a disabled vehicle at or near the shoulder of the Pulaski Skyway. The disabled car had stalled in the right lane of the roadway and its owner, Deloris Haynes, had left the car to seek help. Plaintiff, Paul Caldwell, who remained in the disabled vehicle, was injured by the impact. Caldwell, who was thirty-five-years-old at the time of the accident, was examined and treated over the years by various doctors and hospitals. For almost a year after the May 1987 accident, Caldwell continued treatment with Dr. Sherman, a board-certified internist, who initially treated Caldwell for a spasm, tenderness, and a reduced range of motion in his back. Despite Caldwell's treatment, he remained in pain. Eventually, Dr. Sherman suspected the "possibility of tuberculosis of the spine." Dr. Sherman testified that in his opinion "the accident unmasked or reactivated latent tuberculosis" because he could find no other provoking factors, and medical literature indicated that "significant auto trauma can be a provoking factor." Later, Caldwell began treatment with Dr. Lee, an orthopedic surgeon. In late 1990 , Dr. Lee admitted Caldwell to the hospital because Caldwell was still experiencing back pain and his "right leg was still getting numb every now and then." Caldwell testified that Dr. Lee told him he had tuberculosis of the spine. Dr. Lee's discharge summary indicated the final diagnosis as post-traumatic lumbosacral sprain with spasms, psoas abscess with multiple lumbar abscesses, suspected tuberculosis, and osteomyelitis with the destruction of certain vertebrae. Apparently, Dr. Lee's antibiotic treatment of Caldwell ended the progress of the disease. No evidence suggested that further destruction of spinal bone or other increase in disability had occurred or would occur in the future. Caldwell testified that his back pain was "sharp," he was "in constant pain every day," and "everything became a problem," including tying his shoes, walking, and driving. Caldwell denied ever having had any back pain before the accident. Before the accident, the plaintiff had been employed for two to three years as a general laborer by a construction company that repaired bridges and tunnels. At the time of the accident, Caldwell earned \$25.65 per hour and worked forty or forty-five hours per week, although his hours varied, seemingly due to the seasonal nature of the work. After the accident, Caldwell missed three months of work. Caldwell testified that at the construction company he earned an average gross weekly income of about $1,000. His testimony suggested that his pre-accident annual salary before taxes had been about $ 44,000 . Caldwell stated that in 1987 , the year of the accident in which he missed three months of work, he had earned $ 33,000 . However, Caldwell estimated that his gross wages for the previous year in his work for the same company were only "twenty something" thousand. After the accident and the three-month absence, Caldwell continued working for the 4 company, with lighter work assignments but at the same salary, until July 1990, more than three years after the accident. In July 1990 , the company discharged Caldwell. Caldwell testified that he had been fired because he could no longer "do the strenuous work that it would take to do ... the lifting, and other things like that." Caldwell also stated that "[b]eing terminated with a construction company means you can be fired one day and back at work the next day just because, you know ... [t]here's quite a few they would fire one week, hire back the next week. So I was just one of them." That was the first time the company fired Caldwell. He did not seek to be rehired. Caldwell remained unemployed for a period of eighteen or nineteen months. In February or March 1992, he found work driving a senior citizens' van twenty hours a week at $5.50 per hour. At the time of trial, Caldwell was earning a little over $6,000 per year. He said he was capable of driving a full week, but the job offered only twenty hours. Thus, in addition to the initial threemonth absence from work, Caldwell missed eighteen or nineteen months between the construction and the driving job. Then, he worked part-time during a five- or six-month period during which he had the twenty-hourper-week driving job. Ultimately, the jury found defendant Todd Khler 100% liable and awarded Caldwell a total of $1,550,000:$50,000 for past lost wages and $1.5 million for future lost wages. On appeal, defendant-appellant sought an order for a new trial on the computation of future lost wages. II. In assessing whether the quantum of damages assessed by the jury is excessive, a trial court must consider the evidence in the light most favorable to the prevailing party in the verdict. Taweel v. Starn's Shoprite Supermarket, 276 A.2d 861 (1971). Therefore, a trial court should not interfere with a jury verdict unless the verdict is clearly against the weight of the evidence. Horn v. Village Supermarkets, Inc., 615 A.2d 663 (App. Div. 1992). The verdict must shock the judicial conscience. Carey v. Lovett, 622 A.2d 1279 (1993). III. The principal goal of damages in personalinjury actions is to compensate fairly the injured party. Deemer v. Silk City Textile Mach. Co., 475 A.2d 648 (App.Div. 1984). Fair compensatory damages resulting from the tortious infliction of injury encompass no more than the amount that will make the plaintiff whole, that is, the actual loss. Ruff v. Weintraub, 519 A.2d 1384 (1987). "The purpose, then, of personal injury compensation is neither to reward the plaintiff, nor to punish the defendant, but to replace plaintiff's losses." Domeracki v. Humble Oil \& Ref. Co., 443 F.2d 1245, 1250 (3d Cir.), (1971). A. An injured party has the right to be compensated for diminished earning capacity. Smith v. Red Top Taxicab Corp., 168 A. 796 (E. \& A.1933). The measure of damages for tort recovery encompassing diminished earning capacity can be based on the wages lost as a result of the defendant's wrongdoing. Ibid. That measure includes the value of the decrease in the plaintiff's future earning capacity. Coll v. Sherry, 176, 148 A.2d 481 (1959). When the effects of the injury will extend into the future, "the plaintiff is entitled to further compensation -- for [the] capacity to earn in the future has been taken from the plaintiff, either in whole or in part." Robert J. Nordstrom, Income Taxes and Personal Injury Awards, 19 Ohio St.L.J. 213, 217 (1958). However, the evaluation of such a decrease in future earning capacity is necessarily complicated by the uncertainties of the future. Although generally objectionable for the reason that their estimation is conjectural and speculative, loss of future income dependent upon future events are allowed where their nature and occurrence can be shown by evidence of reasonable reliability. Case precedent recognize and apply the general principle that damages for the loss of future income are recoverable 5 where the evidence makes reasonably certain their occurrence and extent. The award of damages for loss of future income depends upon whether there is a satisfactory basis for estimating what the probable earnings would have been had there been no tort. A satisfactory basis for an existing basis may include reliance on specific economic or statistical models based on past earnings record. See Tenore v. Nu Car Carriers, Inc., 67 N.J. 466, 494, 341 A.2d 613 (1975). The "proper measure of damages for lost future income in personal-injury cases is net income after taxes." Ruff, supra, 105 N.J. at 238, 519 A.2d 1384. The net-income rule embodies the principle that "damages in personal-injury actions should reflect, as closely as possible, the plaintiff's actual loss." Ibid.; see Tenore, supra, 67 N.J. at 477,341 A.2d 613. Hence, "If plaintiff gets, in tax-free damages, an amount on which he would have had to pay taxes if he had gotten it as wages, then plaintiff is getting more than he lost." 4 Fowler V. Harper et al., The Law of Torts 25.12 (2d ed. 1986); see Ruff, supra, 105 N.J. at 238,519 A.2d 1384. The measurement of after tax income is the "more accurate, and therefore proper, measure of damages," Ruff, supra, 105 N.J. at 241, 519 A.2d 1384, because personal-injury damage awards are subject to neither federal nor state taxes. 26 U.S.C. 104(a)(2); N.J.S.A. 54A: 6-6. See generally Annotation, John E. Theuman, Propriety of Taking Income Tax into Consideration in Fixing Damages in Personal Injury or Death Action, 16 A.L.R.4th 589, 611 (1982 \& Supp.1993). Evidence of loss of future income must be discounted to present value, a procedure that recognizes that the injured party would have had his income spread out over the remaining years of his working life. Tenore, supra, 67 N.J. at 474, 341 A.2d 613. In this case, the jury apparently based its future-lost-income award of $1.5 million only on Caldwell's gross income, given that neither plaintiff nor defendant presented any evidence of net income. The jury probably had calculated the future lost wages award by multiplying the gross income figure of $ 1,000 per week by the number of weeks of Caldwell's life expectancy. The jury may have reasonably concluded that plaintiff used to make $1,000 per week but, despite his demonstrated desire to work steadily and hard, he was now doomed to jobs paying no more than his current earnings of $120 per week for the rest of his life. Despite the absence of evidence of plaintiff's net income, the trial court instructed the jury to use net income as the measure of lost wages. Nevertheless, the jury seemingly did not attempt to ascertain or apply net income in its computation of the award. See Lesniak v. County of Bergen, 117 N.J. 12, 28-29, 563 A.2d 795 (1989). In this case, neither party presented the jury with evidence of plaintiff's net income. The deficiencies in the evidence led the jury to reach exaggerated awards for future income. The verdict obviously was distorted by evidence that was limited to gross income. In a fifty-week year, Caldwell would lose gross earnings of $880 per week or $ 44,000 per year. We may surmise that the jury had multiplied Caldwell's life expectancy of 34.55 years by the $44,000 in lost gross earnings to arrive at $1,520,000, which was rounded down to $1,500,000. That award contemplated plaintiff working for 2,083 straight weeks without vacation, or over forty years until the age of eighty, again based on defendant's gross, not net, income. A verdict based on evidence of net income would clearly have brought the jury to a different result. Assuming the Appellate Division's hypothesis was correct, the jury simply multiplied Caldwell's gross income by his life expectancy to reach an award of $ 1.5 million. Accepting Caldwell's testimony that he had earned $1,000 in gross weekly income, and assuming federal and state tax liability to be 28%, his after-tax income would have been $720. Plaintiff was fortyyears-old at the date of the verdict. If the net income figure were multiplied by Caldwell's life expectancy of 34.55 years, even assuming plaintiff worked all fifty-two weeks a year, at most the verdict would approximate $1,290,000. 6 Furthermore, if the jury had based its calculations using work-life expectancy, twenty-five years, again assuming plaintiff worked fifty-two weeks a year, his future lost wages based on net income would equal \$936,000 (\$37,440 net annual income multiplied by twenty-five years). Moreover, the income award would have been reduced even further based on plaintiff's earnings as a van driver. Lastly, the income award would have been reduced even more had the jury calculated the present value of the computed award. We conclude that the damages award based on lost future income, was clearly excessive and must be set aside. It was excessive since it used gross income figures, and not net income figures. Also, it was excessive because it failed to base the award on the work life expectancy of the plaintiff. Lastly, it was excessive since the award was not based on the present value of the future lost income. We, therefore, remand for a retrial of those damages. ROY THOMPSON ET AL. v. PAUL C. LeBLANC ET AL. No. 10782 Court of Appeal of Green, First Circuit COUNSEL: Walton J. Barnes, Baton Rouge, for Appellants. Gordon R. Crawford, Gonzales, for Appellees. JUDGES: Landry, Covington and Ponder, JJ. OPINION: Plaintiffs Roy and Bernice Thompson, husband and wife (Appellants), appeal from judgment dismissing their suit for damages for the alleged false imprisonment of Mrs. Thompson by defendant Larry LeBlanc (LeBlanc), employee of defendant Paul C. LeBlanc (Owner), principal shareholder of an establishment known as Janice LeBlanc's Style Shop (Shop), for suspected shoplifting. We affirm. Although the testimony of the numerous witnesses called at the trial is conflicting in some respects, the trial court has favored us with excellent oral findings of fact dictated into the record. We are in agreement with these findings which are substantially as follows: Early in the afternoon of July 11, 1993, Mrs. Thompson and her children, Joyce, aged 16, Donald, aged 15, and Roy aged 11, were shopping at the Gonzales Mall, in which the Shop is located. They entered the Shop, an establishment dealing primarily in women's apparel, to purchase clothing for Joyce who was contemplating a school trip. The daughter tried on and ultimately purchased three pairs of pants and one top or blouse, which items were admittedly paid for and delivered to the purchaser in one of the Shop's distinctive pink bags by Shop employees. It appears that the other members of the family entertained themselves during the shopping episode, either by looking at the merchandise in the store or assisting Miss Thompson in making her selections. When the Thompson family entered the Shop, Mrs. Janice LeBlanc, Owner's wife, and an employee, Irene Gregoire were having lunch in the Shop office situated at the rear of the establishment. The evidence preponderates to the effect that when the Thompsons came into the Shop, there were no customers in the establishment. It is also shown that in addition to Mrs. LeBlanc and Mrs. Gregoire, two other employees were present. The office was equipped with a twoway mirror through which its occupants could view the interior of the establishment. Mrs. LeBlanc and Mrs. Gregoire observed the Thompsons enter the store together and immediately separate, in which circumstance they were trained to suspect a possible shoplifting incident, especially since Mrs. Thompson was carrying a large purse. Through the mirror they observed as Mrs. Thompson looked through a rack of swimsuits located near the front entrance while at the same time opening her purse. At this same time, one of the Thompson boys passed between his mother and the mirror, apparently while Mrs. Thompson was either opening or fingering her purse, which circumstance caused Mrs. LeBlanc and Mrs. Gregoire to believe they saw Mrs. Thompson place a swimsuit in her purse. Either Mrs. LeBlanc or some other personnel of the store immediately checked the swimsuit rack and found an empty hanger where Mrs. Thompson had been looking at the swimsuits. In accordance with Owner's standing instructions, Mrs. LeBlanc telephoned Larry LeBlanc, who was employed in another of Owner's shops located across the mall of the shopping center, and requested that he come to the shop immediately. LeBlanc arrived while the Thompsons were still in the store. He immediately telephoned and requested the police to send someone to investigate the incident. He kept the Thompsons under observation until the Thompsons left the store approximately five minutes after LeBlanc phoned for the police. He watched as the Thompsons exited the Shop and crossed the mall to a fabric store situated directly across from the Shop. The Thompsons remained in the fabric shop for 8 5 to 10 minutes and re-crossed the mall to visit a card and novelty store next to the Shop. After completing her visit to the card shop, Mrs. Thompson, accompanied by the children, proceeded to leave the mall in the direction of the parking lot. En route to the parking lot, Mrs. Thompson again passed the Shop, at which point LeBlanc realized she would leave the premises before the police arrived. As Mrs. Thompson neared the front door of the Shop, LeBlanc approached Mrs. Thompson and requested that she return to the shop so that the ladies there could look into her purse because they suspected her of shoplifting. Mrs. Thompson reacted with surprise and disbelief because she at first did not think LeBlanc was addressing her. LeBlanc then repeated his request whereupon Mrs. Thompson protested her innocence and refused to reenter the Shop. Upon the urging of her children, particularly the daughter who suggested that her mother should prove her innocence, Mrs. Thompson voluntarily reentered the Shop. It is conceded that LeBlanc did not threaten, coerce or attempt to intimidate Mrs. Thompson in any manner whatsoever. It is also admitted that he used no abusive language and did not threaten Mrs. Thompson with arrest. Mrs. Thompson was understandably upset over the accusation. LeBlanc opened the door of the Shop for Mrs. Thompson who proceeded immediately to the check out counter where, without further request from Shop personnel, she removed several large items from her purse, placed them on the counter, and emptied the remaining contents onto the counter. Mrs. LeBlanc or some other Shop personnel examined the purse but found nothing incriminating, either in the purse or on the counter. Mrs. LeBlanc apologized for the inconvenience caused Mrs. Thompson. Mrs. Thompson then asked Mrs. LeBlanc to identify herself, and upon learning Mrs. LeBlanc's name, Mrs. Thompson told Mrs. LeBlanc she would hear from Mrs. Thompson's attorney. With that, Mrs. Thompson left the establishment. At no time did the police appear at the scene. The record establishes conclusively that except perhaps for the Thompson children, Mrs. Thompson was the only person other than Shop personnel in the shop when she entered the store at LeBlanc's request. The evidence is conflicting whether the Thompson children followed their mother into the establishment. Mrs. Thompson and the children testified that the children did accompany their mother when she reentered the Shop. Mrs. LeBlanc, LeBlanc, Mrs. Gregoire and one or two other employees testified that Mrs. Thompson entered the Shop alone. The trial court concluded that LeBlanc was authorized by Owner to detain and question suspected shoplifters and that the detention in question was privileged because LeBlanc acted with reasonable cause and exercised reasonable measures under the circumstances. Appellants contend that the trial court erred in the following determinations: (1) holding that reasonable cause existed when the detention was made by a party without personal knowledge of the events upon which the detention was based; (2) holding that the search was reasonable notwithstanding that it was conducted in a public area of the Shop instead of in the privacy of the office or some other nonpublic area of the Shop; and (3) holding that the detention was privileged even though it was not made on the premises but in a public area of the shopping center. Defendants invoke the privilege extended to shopkeepers pursuant to Green Code Crim.Pro.Art. 215 which pertinently provides: "Art. 215. Detention and arrest of shoplifters A peace officer, merchant, or a specifically authorized employee of a merchant, may use reasonable force to detain a person for questioning on the merchant's premises, for a reasonable length of time, when he has reasonable cause to believe that the person has committed theft of goods held for sale by the merchant, regardless of the actual value of the goods. The detention shall not constitute false imprisonment." To meet the requirements of an authorized detention, as defined in Article 215, above, it must be shown: (1) The person effecting the detention must be a peace officer, a merchant or a specifically authorized employee of a merchant; (2) The party making the detention must have reasonable cause to believe that the detained person has committed theft. Reasonable cause requires that the detaining officer have articuable knowledge of particular facts sufficiently reasonably to suspect the detained person of shoplifting. To have articulable knowledge, the merchant must conduct preliminary investigation of his suspicions, if time permits.; (3) the detention was conducted in a reasonable manner. In determining whether detention was conducted in a reasonable manner, courts examine the following factors: (a) whether the merchant threatened the customer with arrest; (b) whether the merchant coerced the customer; (c) whether the merchant attempted to intimidate the customer; (d) whether the merchant used abuse language towards the customer; (e) whether the merchant used forced against the customer; (f) whether the merchant promptly informed the customer of the reasons for the detention; and (g) whether the detention took place in public next to others. (4) The detention must occur on the merchant's premises; and (5) The detention may not last longer than for a reasonable period of time. The testimony supports the trial court's finding that LeBlanc was authorized by Owner to detain customers suspected of shoplifting. Mrs. LeBlanc and Mrs. Gregoire testified they were under standing orders from Owner to call Mr. LeBlanc, who worked in another of Owner's shops across the mall, whenever the employees of the Shop suspected an incident of shoplifting. The testimony also shows that these ladies had in fact called Mr. LeBlanc for such purpose on many prior occasions, all of which testimony was fully corroborated both by Owner and LeBlanc. As did the trial court, we find LeBlanc had reasonable cause to believe that a theft had occurred. Considering the circumstances, including the facts that Mrs. Thompson was carrying a very large purse, that she was observed handling the bathing suits, that the Shop employees saw what they considered a suspicious move by Mrs. Thompson and that an empty hanger was seen on the rack after Mrs. Thompson left the area where the bathing suits were displayed, we find it reasonable that the employees suspected a theft had occurred. We find that LeBlanc acted reasonably in the manner in which he detained Mrs. Thompson. It is conceded he never touched or threatened Mrs. Thompson but that he politely requested her to return to the Shop and advised her that the reason for his request was that she was suspected of shoplifting. On Mrs. Thompson's refusal, LeBlanc made no further request and Mrs. Thompson's decision to re-enter the establishment was made upon the urging of her children that she establish her innocence of the charge. It is also shown that Mrs. Thompson hastily entered the store ahead of LeBlanc who held the door open for her. She proceeded directly to the check-out counter where she immediately emptied her purse before anything was said by LeBlanc or any other employee of the establishment. There were no other customers in the Shop, save the possible exception of the Thompson children. That the incident occurred in a public portion of the shop under these circumstances, does not constitute unreasonableness on the part of the employees involved. Finally, the fact that the detention occurred in front of the Shop and not within the store does not defeat the merchant's statutory privilege. The record establishes that the detention occurred on a sidewalk or walkway within a few feet of the door of the Shop. Sidewalks immediately in front of a merchandising establishment are considered part of the premises for purposes of application of Green Code Crim.Pro.Art. 215. Durand v. United Dollar Store of Hammond, Inc., above; Eason v. J. Weingarten, Inc., La.App., 219 So.2d 516; Simmons v. J. C. Penney Company, La.App., 186 So.2d. 358. The judgment of the trial court is affirmed, all costs of these proceedings to be paid by Appellants. Affirmed. Daniel Baker, Customer Relations Manager, for Color Theory, was in a quandary. He pondered over a memo from James Power, Loss Prevention Manager at Color Theory, (Exhibit 1) and a letter addressed to him from Megan Ivory, a customer, (Exhibit 2). What appeared to have been a routine shoplifting incident on the part of Mrs. Ivory turned out to lack evidence. To make matters worse, the suspect was injured during apprehension. It appeared that Color Theory faced the possibility of a lawsuit because of the incident. Mason Miles, the Chief Administrator, had asked Mr. Baker to assess the legal and financial consequences of the case, make recommendations, and report back to him. Color Theory is a large stationery and drawing supplies retailer with approximately 50 stores located throughout the State of Green. The firm has been established for many years, making steady, if unspectacular profits. EXHIBIT 1 MEMORA N D UM DATE: TO: FROM: SUBJECT: January 3,2022 File James Power, Loss Prevention Manager Shoplifting Incident At 1:50 p.m. today, I observed a customer, Megan Ivory, who was standing next to calligraphy sets in the store, make a sudden move to her pocket. She then proceeded at an accelerated pace toward the exit. I noticed that her side pocket was stuffed. I then proceeded directly to where the customer had been standing and noticed that a calligraphy pen set was missing. It so happened that I noticed earlier that day that the calligraphy pen sets were fully stocked up. I assumed that the customer, who I had previously observed, had shoplifted the set. As the customer was about to leave the store by then, I began chasing after her and reached her at the store's entrance. Fearing that I might lose her in the crowd, I shouted at her to stop. I then grasped her by the arm and shoved her back to the store. Apparently, the customer lost her balance and fell on her back hitting one of the checkout counters. She seemed to be hurt a little, but then I offered to help her stand up, although she continued to limp. I then asked her if she had forgotten to pay for something. She seemed surprised and said that she does not understand what I am talking about. I then directed her to follow me to the Loss Prevention room. Diana Rhead, one of the checkout employees, helped her walk toward the Loss Prevention room as the customer complained she was having difficulty walking and was experiencing terrible back pain. I closely walked behind the two of them. Per the store's protocol, I then advised the customer that she would have to wait until the store's manager came back from a meeting for the investigation to begin. The store's manager, Sandra Brooks, was due to return from a meeting at 2:15 p.m. that day. Unfortunately, she only returned at 3:15 p.m. At that time, Mrs. Brooks advised the customer why she was being held up and asked her to empty her pockets. However, no calligraphy set was found. Mrs. Brooks then apologized for the inconvenience, gave her a $30 gift certificate, and wished the customer well. I really did not mean to hurt the customer, but apparently, her fall did some damage to her as she kept complaining that her back hurts. EXHIBIT 2 Megan Ivory 88 Blue Street Orange City, Green February 18,2022 Mason Miles, Chief Administrator Color Theory 33 Navy Blvd. Peach City, Green Re: incident dated January 3rd,2022 Dear Mr. Miles: Based on permanent injuries inflicted on me by one of your employees while falsely imprisoning me on January 3rd, 2022 , I demand compensation in the sum of $665,000 in medical care expenses and $700,000 for the loss of future income. On January 3rd,2022, I came to your store to locate some art supplies for my daughter's art project at school. While I was examining a number of calligraphy sets that you had on the shelves, I was not able to find the calligraphy set my daughter's teacher requested. Rushed to make it back to an appointment I had with a client that afternoon, I headed toward the store's exit. As I was about to leave the store's premises, I heard someone shout behind me ordering me to stop immediately while using some foul language. When I looked back, I saw a six-foot, two-hundred-pound man grabbing my arm and shoving me back to the store. Due to the tremendous force of that shoving, I lost balance and fell on my back, right against one of the store's checkout counters. I immediately felt extreme pain in my back and was unable to move. I was then helped out by a store employee and was ordered to go to the Loss Prevention room. I was told that police would be called to the premises if I did not directly go to the Loss Prevention room. There were approximately twenty-five customers watching me as I was escorted to the Loss Prevention room. I felt extremely embarrassed by the ordeal. Once we got to the Loss Prevention room, I asked the man, who accosted me at the store's entrance and who then followed me to the room, the reason for my detention. He then mentioned that it is against the store's policy for him to discuss the matter further and that I would have to wait for the store's manager. Almost an hour later, the store manager, Mrs. Brooks, arrived. At that point, she notified me that I have been detained because one of the store's employees had observed me stealing a calligraphy pen set. I immediately denied any involvement in the matter and offered to empty my pockets. Mrs. Brooks was then satisfied that I had done nothing wrong. She politely apologized and allowed me to leave the store's premises. Later that afternoon, I was admitted to Cedars Sinai Hospital emergency room as I was experiencing severe back pain arising out of my fall earlier that day. That same night, a team of surgeons operated on my back as the condition severely deteriorated. However, they were unable to successfully treat the back injuries in this and in two other surgeries that followed. I am now diagnosed with an abnormal degeneration of my spine resulting in irreparable back injury and permanent disability. This condition prevents me from ever walking again or from ever sitting down for more than ten minutes at a time. As a result of this permanent condition, I had to quit my job as a regional salesperson for Purple Care, a pharmaceutical company. My doctor's diagnosis indicates that these injuries to my back would prevent me from ever working again. Besides my past and future medical bills, I am also demanding that you compensate me for the loss of future income. As a forty-nine years old, highly successful career woman in the field of pharmaceutical sales, I am now deprived of any prospects of employment for the rest of my life. I am attaching a copy of my gross yearly income from my sales position during the last eighteen years. (See Exhibit 3). Please respond to my settlement offer on or before April 15. I hope this matter could be resolved amicably. Sincerely, Megan Ivory Enclosures EXHIBIT 3 * Source: https://data.bls.gov/pdq/SurveyOutputServlet U.S. Department of Labor, Urban Consumers, 19821984=100 Required: Suppose you are Daniel Baker. You have just confirmed that, for all practical purposes, Mrs. Ivory will be unable to work at all during the next sixteen years, including all of 2022. Write a report, addressed to Mason Miles, Chief Administrator of Color Theory. Be sure to follow the guidelines for writing a report found on the Gateway Website. To prepare for this case, you may want to review business law LDC concepts 2 and 9 , financial accounting LDC concept 7 , macroeconomics LDC concept 1 , and statistics LDC concepts 1,4 , and 8. COLOR THEORY LIBRARY PAUL CALDWELL, PLAINTIFFRESPONDENT, v. TODD KHLER DEFENDANT-APPELLANT A-108 September Term 1993 Supreme Court of Green March 14, 1994, Argued July 6, 1994, Decided PRIOR HISTORY: [**1] COUNSEL: W. Stephen Leary argued the cause for appellant. Raymond T. Roche argued the cause for respondent OPINIONBY: HANDLER OPINION: On May 21, 1987, Todd Khler (hereinafter defendant), who was operating a car struck the rear end of a disabled vehicle at or near the shoulder of the Pulaski Skyway. The disabled car had stalled in the right lane of the roadway and its owner, Deloris Haynes, had left the car to seek help. Plaintiff, Paul Caldwell, who remained in the disabled vehicle, was injured by the impact. Caldwell, who was thirty-five-years-old at the time of the accident, was examined and treated over the years by various doctors and hospitals. For almost a year after the May 1987 accident, Caldwell continued treatment with Dr. Sherman, a board-certified internist, who initially treated Caldwell for a spasm, tenderness, and a reduced range of motion in his back. Despite Caldwell's treatment, he remained in pain. Eventually, Dr. Sherman suspected the "possibility of tuberculosis of the spine." Dr. Sherman testified that in his opinion "the accident unmasked or reactivated latent tuberculosis" because he could find no other provoking factors, and medical literature indicated that "significant auto trauma can be a provoking factor." Later, Caldwell began treatment with Dr. Lee, an orthopedic surgeon. In late 1990 , Dr. Lee admitted Caldwell to the hospital because Caldwell was still experiencing back pain and his "right leg was still getting numb every now and then." Caldwell testified that Dr. Lee told him he had tuberculosis of the spine. Dr. Lee's discharge summary indicated the final diagnosis as post-traumatic lumbosacral sprain with spasms, psoas abscess with multiple lumbar abscesses, suspected tuberculosis, and osteomyelitis with the destruction of certain vertebrae. Apparently, Dr. Lee's antibiotic treatment of Caldwell ended the progress of the disease. No evidence suggested that further destruction of spinal bone or other increase in disability had occurred or would occur in the future. Caldwell testified that his back pain was "sharp," he was "in constant pain every day," and "everything became a problem," including tying his shoes, walking, and driving. Caldwell denied ever having had any back pain before the accident. Before the accident, the plaintiff had been employed for two to three years as a general laborer by a construction company that repaired bridges and tunnels. At the time of the accident, Caldwell earned \$25.65 per hour and worked forty or forty-five hours per week, although his hours varied, seemingly due to the seasonal nature of the work. After the accident, Caldwell missed three months of work. Caldwell testified that at the construction company he earned an average gross weekly income of about $1,000. His testimony suggested that his pre-accident annual salary before taxes had been about $ 44,000 . Caldwell stated that in 1987 , the year of the accident in which he missed three months of work, he had earned $ 33,000 . However, Caldwell estimated that his gross wages for the previous year in his work for the same company were only "twenty something" thousand. After the accident and the three-month absence, Caldwell continued working for the 4 company, with lighter work assignments but at the same salary, until July 1990, more than three years after the accident. In July 1990 , the company discharged Caldwell. Caldwell testified that he had been fired because he could no longer "do the strenuous work that it would take to do ... the lifting, and other things like that." Caldwell also stated that "[b]eing terminated with a construction company means you can be fired one day and back at work the next day just because, you know ... [t]here's quite a few they would fire one week, hire back the next week. So I was just one of them." That was the first time the company fired Caldwell. He did not seek to be rehired. Caldwell remained unemployed for a period of eighteen or nineteen months. In February or March 1992, he found work driving a senior citizens' van twenty hours a week at $5.50 per hour. At the time of trial, Caldwell was earning a little over $6,000 per year. He said he was capable of driving a full week, but the job offered only twenty hours. Thus, in addition to the initial threemonth absence from work, Caldwell missed eighteen or nineteen months between the construction and the driving job. Then, he worked part-time during a five- or six-month period during which he had the twenty-hourper-week driving job. Ultimately, the jury found defendant Todd Khler 100% liable and awarded Caldwell a total of $1,550,000:$50,000 for past lost wages and $1.5 million for future lost wages. On appeal, defendant-appellant sought an order for a new trial on the computation of future lost wages. II. In assessing whether the quantum of damages assessed by the jury is excessive, a trial court must consider the evidence in the light most favorable to the prevailing party in the verdict. Taweel v. Starn's Shoprite Supermarket, 276 A.2d 861 (1971). Therefore, a trial court should not interfere with a jury verdict unless the verdict is clearly against the weight of the evidence. Horn v. Village Supermarkets, Inc., 615 A.2d 663 (App. Div. 1992). The verdict must shock the judicial conscience. Carey v. Lovett, 622 A.2d 1279 (1993). III. The principal goal of damages in personalinjury actions is to compensate fairly the injured party. Deemer v. Silk City Textile Mach. Co., 475 A.2d 648 (App.Div. 1984). Fair compensatory damages resulting from the tortious infliction of injury encompass no more than the amount that will make the plaintiff whole, that is, the actual loss. Ruff v. Weintraub, 519 A.2d 1384 (1987). "The purpose, then, of personal injury compensation is neither to reward the plaintiff, nor to punish the defendant, but to replace plaintiff's losses." Domeracki v. Humble Oil \& Ref. Co., 443 F.2d 1245, 1250 (3d Cir.), (1971). A. An injured party has the right to be compensated for diminished earning capacity. Smith v. Red Top Taxicab Corp., 168 A. 796 (E. \& A.1933). The measure of damages for tort recovery encompassing diminished earning capacity can be based on the wages lost as a result of the defendant's wrongdoing. Ibid. That measure includes the value of the decrease in the plaintiff's future earning capacity. Coll v. Sherry, 176, 148 A.2d 481 (1959). When the effects of the injury will extend into the future, "the plaintiff is entitled to further compensation -- for [the] capacity to earn in the future has been taken from the plaintiff, either in whole or in part." Robert J. Nordstrom, Income Taxes and Personal Injury Awards, 19 Ohio St.L.J. 213, 217 (1958). However, the evaluation of such a decrease in future earning capacity is necessarily complicated by the uncertainties of the future. Although generally objectionable for the reason that their estimation is conjectural and speculative, loss of future income dependent upon future events are allowed where their nature and occurrence can be shown by evidence of reasonable reliability. Case precedent recognize and apply the general principle that damages for the loss of future income are recoverable 5 where the evidence makes reasonably certain their occurrence and extent. The award of damages for loss of future income depends upon whether there is a satisfactory basis for estimating what the probable earnings would have been had there been no tort. A satisfactory basis for an existing basis may include reliance on specific economic or statistical models based on past earnings record. See Tenore v. Nu Car Carriers, Inc., 67 N.J. 466, 494, 341 A.2d 613 (1975). The "proper measure of damages for lost future income in personal-injury cases is net income after taxes." Ruff, supra, 105 N.J. at 238, 519 A.2d 1384. The net-income rule embodies the principle that "damages in personal-injury actions should reflect, as closely as possible, the plaintiff's actual loss." Ibid.; see Tenore, supra, 67 N.J. at 477,341 A.2d 613. Hence, "If plaintiff gets, in tax-free damages, an amount on which he would have had to pay taxes if he had gotten it as wages, then plaintiff is getting more than he lost." 4 Fowler V. Harper et al., The Law of Torts 25.12 (2d ed. 1986); see Ruff, supra, 105 N.J. at 238,519 A.2d 1384. The measurement of after tax income is the "more accurate, and therefore proper, measure of damages," Ruff, supra, 105 N.J. at 241, 519 A.2d 1384, because personal-injury damage awards are subject to neither federal nor state taxes. 26 U.S.C. 104(a)(2); N.J.S.A. 54A: 6-6. See generally Annotation, John E. Theuman, Propriety of Taking Income Tax into Consideration in Fixing Damages in Personal Injury or Death Action, 16 A.L.R.4th 589, 611 (1982 \& Supp.1993). Evidence of loss of future income must be discounted to present value, a procedure that recognizes that the injured party would have had his income spread out over the remaining years of his working life. Tenore, supra, 67 N.J. at 474, 341 A.2d 613. In this case, the jury apparently based its future-lost-income award of $1.5 million only on Caldwell's gross income, given that neither plaintiff nor defendant presented any evidence of net income. The jury probably had calculated the future lost wages award by multiplying the gross income figure of $ 1,000 per week by the number of weeks of Caldwell's life expectancy. The jury may have reasonably concluded that plaintiff used to make $1,000 per week but, despite his demonstrated desire to work steadily and hard, he was now doomed to jobs paying no more than his current earnings of $120 per week for the rest of his life. Despite the absence of evidence of plaintiff's net income, the trial court instructed the jury to use net income as the measure of lost wages. Nevertheless, the jury seemingly did not attempt to ascertain or apply net income in its computation of the award. See Lesniak v. County of Bergen, 117 N.J. 12, 28-29, 563 A.2d 795 (1989). In this case, neither party presented the jury with evidence of plaintiff's net income. The deficiencies in the evidence led the jury to reach exaggerated awards for future income. The verdict obviously was distorted by evidence that was limited to gross income. In a fifty-week year, Caldwell would lose gross earnings of $880 per week or $ 44,000 per year. We may surmise that the jury had multiplied Caldwell's life expectancy of 34.55 years by the $44,000 in lost gross earnings to arrive at $1,520,000, which was rounded down to $1,500,000. That award contemplated plaintiff working for 2,083 straight weeks without vacation, or over forty years until the age of eighty, again based on defendant's gross, not net, income. A verdict based on evidence of net income would clearly have brought the jury to a different result. Assuming the Appellate Division's hypothesis was correct, the jury simply multiplied Caldwell's gross income by his life expectancy to reach an award of $ 1.5 million. Accepting Caldwell's testimony that he had earned $1,000 in gross weekly income, and assuming federal and state tax liability to be 28%, his after-tax income would have been $720. Plaintiff was fortyyears-old at the date of the verdict. If the net income figure were multiplied by Caldwell's life expectancy of 34.55 years, even assuming plaintiff worked all fifty-two weeks a year, at most the verdict would approximate $1,290,000. 6 Furthermore, if the jury had based its calculations using work-life expectancy, twenty-five years, again assuming plaintiff worked fifty-two weeks a year, his future lost wages based on net income would equal \$936,000 (\$37,440 net annual income multiplied by twenty-five years). Moreover, the income award would have been reduced even further based on plaintiff's earnings as a van driver. Lastly, the income award would have been reduced even more had the jury calculated the present value of the computed award. We conclude that the damages award based on lost future income, was clearly excessive and must be set aside. It was excessive since it used gross income figures, and not net income figures. Also, it was excessive because it failed to base the award on the work life expectancy of the plaintiff. Lastly, it was excessive since the award was not based on the present value of the future lost income. We, therefore, remand for a retrial of those damages. ROY THOMPSON ET AL. v. PAUL C. LeBLANC ET AL. No. 10782 Court of Appeal of Green, First Circuit COUNSEL: Walton J. Barnes, Baton Rouge, for Appellants. Gordon R. Crawford, Gonzales, for Appellees. JUDGES: Landry, Covington and Ponder, JJ. OPINION: Plaintiffs Roy and Bernice Thompson, husband and wife (Appellants), appeal from judgment dismissing their suit for damages for the alleged false imprisonment of Mrs. Thompson by defendant Larry LeBlanc (LeBlanc), employee of defendant Paul C. LeBlanc (Owner), principal shareholder of an establishment known as Janice LeBlanc's Style Shop (Shop), for suspected shoplifting. We affirm. Although the testimony of the numerous witnesses called at the trial is conflicting in some respects, the trial court has favored us with excellent oral findings of fact dictated into the record. We are in agreement with these findings which are substantially as follows: Early in the afternoon of July 11, 1993, Mrs. Thompson and her children, Joyce, aged 16, Donald, aged 15, and Roy aged 11, were shopping at the Gonzales Mall, in which the Shop is located. They entered the Shop, an establishment dealing primarily in women's apparel, to purchase clothing for Joyce who was contemplating a school trip. The daughter tried on and ultimately purchased three pairs of pants and one top or blouse, which items were admittedly paid for and delivered to the purchaser in one of the Shop's distinctive pink bags by Shop employees. It appears that the other members of the family entertained themselves during the shopping episode, either by looking at the merchandise in the store or assisting Miss Thompson in making her selections. When the Thompson family entered the Shop, Mrs. Janice LeBlanc, Owner's wife, and an employee, Irene Gregoire were having lunch in the Shop office situated at the rear of the establishment. The evidence preponderates to the effect that when the Thompsons came into the Shop, there were no customers in the establishment. It is also shown that in addition to Mrs. LeBlanc and Mrs. Gregoire, two other employees were present. The office was equipped with a twoway mirror through which its occupants could view the interior of the establishment. Mrs. LeBlanc and Mrs. Gregoire observed the Thompsons enter the store together and immediately separate, in which circumstance they were trained to suspect a possible shoplifting incident, especially since Mrs. Thompson was carrying a large purse. Through the mirror they observed as Mrs. Thompson looked through a rack of swimsuits located near the front entrance while at the same time opening her purse. At this same time, one of the Thompson boys passed between his mother and the mirror, apparently while Mrs. Thompson was either opening or fingering her purse, which circumstance caused Mrs. LeBlanc and Mrs. Gregoire to believe they saw Mrs. Thompson place a swimsuit in her purse. Either Mrs. LeBlanc or some other personnel of the store immediately checked the swimsuit rack and found an empty hanger where Mrs. Thompson had been looking at the swimsuits. In accordance with Owner's standing instructions, Mrs. LeBlanc telephoned Larry LeBlanc, who was employed in another of Owner's shops located across the mall of the shopping center, and requested that he come to the shop immediately. LeBlanc arrived while the Thompsons were still in the store. He immediately telephoned and requested the police to send someone to investigate the incident. He kept the Thompsons under observation until the Thompsons left the store approximately five minutes after LeBlanc phoned for the police. He watched as the Thompsons exited the Shop and crossed the mall to a fabric store situated directly across from the Shop. The Thompsons remained in the fabric shop for 8 5 to 10 minutes and re-crossed the mall to visit a card and novelty store next to the Shop. After completing her visit to the card shop, Mrs. Thompson, accompanied by the children, proceeded to leave the mall in the direction of the parking lot. En route to the parking lot, Mrs. Thompson again passed the Shop, at which point LeBlanc realized she would leave the premises before the police arrived. As Mrs. Thompson neared the front door of the Shop, LeBlanc approached Mrs. Thompson and requested that she return to the shop so that the ladies there could look into her purse because they suspected her of shoplifting. Mrs. Thompson reacted with surprise and disbelief because she at first did not think LeBlanc was addressing her. LeBlanc then repeated his request whereupon Mrs. Thompson protested her innocence and refused to reenter the Shop. Upon the urging of her children, particularly the daughter who suggested that her mother should prove her innocence, Mrs. Thompson voluntarily reentered the Shop. It is conceded that LeBlanc did not threaten, coerce or attempt to intimidate Mrs. Thompson in any manner whatsoever. It is also admitted that he used no abusive language and did not threaten Mrs. Thompson with arrest. Mrs. Thompson was understandably upset over the accusation. LeBlanc opened the door of the Shop for Mrs. Thompson who proceeded immediately to the check out counter where, without further request from Shop personnel, she removed several large items from her purse, placed them on the counter, and emptied the remaining contents onto the counter. Mrs. LeBlanc or some other Shop personnel examined the purse but found nothing incriminating, either in the purse or on the counter. Mrs. LeBlanc apologized for the inconvenience caused Mrs. Thompson. Mrs. Thompson then asked Mrs. LeBlanc to identify herself, and upon learning Mrs. LeBlanc's name, Mrs. Thompson told Mrs. LeBlanc she would hear from Mrs. Thompson's attorney. With that, Mrs. Thompson left the establishment. At no time did the police appear at the scene. The record establishes conclusively that except perhaps for the Thompson children, Mrs. Thompson was the only person other than Shop personnel in the shop when she entered the store at LeBlanc's request. The evidence is conflicting whether the Thompson children followed their mother into the establishment. Mrs. Thompson and the children testified that the children did accompany their mother when she reentered the Shop. Mrs. LeBlanc, LeBlanc, Mrs. Gregoire and one or two other employees testified that Mrs. Thompson entered the Shop alone. The trial court concluded that LeBlanc was authorized by Owner to detain and question suspected shoplifters and that the detention in question was privileged because LeBlanc acted with reasonable cause and exercised reasonable measures under the circumstances. Appellants contend that the trial court erred in the following determinations: (1) holding that reasonable cause existed when the detention was made by a party without personal knowledge of the events upon which the detention was based; (2) holding that the search was reasonable notwithstanding that it was conducted in a public area of the Shop instead of in the privacy of the office or some other nonpublic area of the Shop; and (3) holding that the detention was privileged even though it was not made on the premises but in a public area of the shopping center. Defendants invoke the privilege extended to shopkeepers pursuant to Green Code Crim.Pro.Art. 215 which pertinently provides: "Art. 215. Detention and arrest of shoplifters A peace officer, merchant, or a specifically authorized employee of a merchant, may use reasonable force to detain a person for questioning on the merchant's premises, for a reasonable length of time, when he has reasonable cause to believe that the person has committed theft of goods held for sale by the merchant, regardless of the actual value of the goods. The detention shall not constitute false imprisonment." To meet the requirements of an authorized detention, as defined in Article 215, above, it must be shown: (1) The person effecting the detention must be a peace officer, a merchant or a specifically authorized employee of a merchant; (2) The party making the detention must have reasonable cause to believe that the detained person has committed theft. Reasonable cause requires that the detaining officer have articuable knowledge of particular facts sufficiently reasonably to suspect the detained person of shoplifting. To have articulable knowledge, the merchant must conduct preliminary investigation of his suspicions, if time permits.; (3) the detention was conducted in a reasonable manner. In determining whether detention was conducted in a reasonable manner, courts examine the following factors: (a) whether the merchant threatened the customer with arrest; (b) whether the merchant coerced the customer; (c) whether the merchant attempted to intimidate the customer; (d) whether the merchant used abuse language towards the customer; (e) whether the merchant used forced against the customer; (f) whether the merchant promptly informed the customer of the reasons for the detention; and (g) whether the detention took place in public next to others. (4) The detention must occur on the merchant's premises; and (5) The detention may not last longer than for a reasonable period of time. The testimony supports the trial court's finding that LeBlanc was authorized by Owner to detain customers suspected of shoplifting. Mrs. LeBlanc and Mrs. Gregoire testified they were under standing orders from Owner to call Mr. LeBlanc, who worked in another of Owner's shops across the mall, whenever the employees of the Shop suspected an incident of shoplifting. The testimony also shows that these ladies had in fact called Mr. LeBlanc for such purpose on many prior occasions, all of which testimony was fully corroborated both by Owner and LeBlanc. As did the trial court, we find LeBlanc had reasonable cause to believe that a theft had occurred. Considering the circumstances, including the facts that Mrs. Thompson was carrying a very large purse, that she was observed handling the bathing suits, that the Shop employees saw what they considered a suspicious move by Mrs. Thompson and that an empty hanger was seen on the rack after Mrs. Thompson left the area where the bathing suits were displayed, we find it reasonable that the employees suspected a theft had occurred. We find that LeBlanc acted reasonably in the manner in which he detained Mrs. Thompson. It is conceded he never touched or threatened Mrs. Thompson but that he politely requested her to return to the Shop and advised her that the reason for his request was that she was suspected of shoplifting. On Mrs. Thompson's refusal, LeBlanc made n