Answered step by step

Verified Expert Solution

Question

1 Approved Answer

Abstract. BACKGROUND: Proponents of telework arrangements assert that those who telework have more control over their work and family domains than their counterparts who

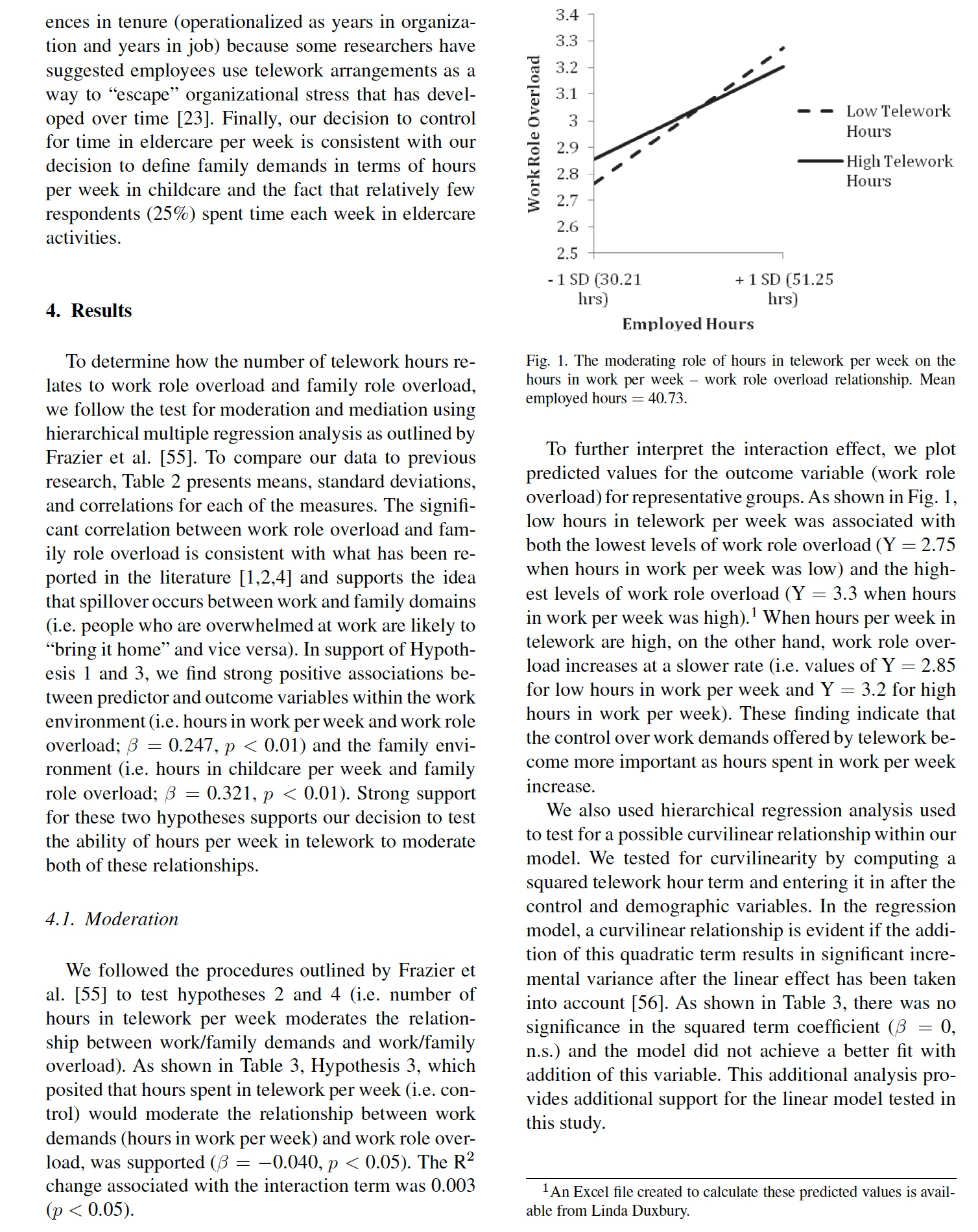

Abstract. BACKGROUND: Proponents of telework arrangements assert that those who telework have more control over their work and family domains than their counterparts who are not permitted to work from home. OBJECTIVE: Using Karasek's theory we hypothesized that the relationship between demands (hours in work per week; hours in childcare per week) and strain (work role overload; family role overload) would be moderated by the number of hours the employee spent per week teleworking (control). METHODS: To determine how the number of telework hours relates to work role overload and family role overload, we follow the test for moderation and mediation using hierarchical multiple regression analysis as outlined by Frazier et al. [50] We used survey data collected from 1,806 male and female professional employees who spent at least one hour per week working from home during regular hours (i.e. teleworking). RESULTS: As hypothesized, the number of hours in telework per week negatively moderated the relation between work demands (total hours in paid employment per week) and work strain (work role overload). Contrary to our hypothesis, the number of hours in telework per week only partially mediated the relation between family demands (hours a week in childcare) and family role. overload (strain). CONCLUSIONS: The findings from this study support the idea that the control offered by telework is domain specific (helps employees meet demands at work but not at home). Keywords: Telecommute, Karasek's demand-control, moderation, mediation (two thirds of the respondents had personal incomes of $60,000 or more per year). More than half the respon- dents were "knowledge workers" with just over 60% of the sample working in managerial and professional po- sitions. In the majority of families represented in this sample (75%) both partners work for pay outside the home. Two thirds of the respondents have children at home. Complete details on the study and the respon- dents can be found in Duxbury and Higgins [50]. The sample used in this study was selected from this larger data set as follows: all respondents were parents who worked full time and spent at least one hour tele- working in the week prior to their completion of the survey. We examined the literature to determine what is currently known with respect to the type of employ- ees who typically telework. This review determined that researchers have looked at two different types of teleworkers: employees in management and profes- sional positions and women in clerical positions [23]. Throughout the remainder of this paper we focus on the former group of teleworkers (i.e., managers and professionals), as findings on this group speak to con- cerns employees have with respect to the recruitment and retention of employees in this group in modern organizations [51]. One thousand eight hundred and nine (1809) respondents fit this criterion. Three obser- vations were removed as they were outliers reported teleworking more hours than they reported working in total. This left 1806 responses for analysis. Sample demographics are shown in Table 1. The majority of the teleworkers in the sample were female (60.3% female). Virtually all respondents were middle aged (average age of 45.1 years) married (80.5%) indi- viduals in the "full nest stage of the lifecycle. Parents spent an average of 11.7 hours per week in childcare. Respondents spent an average of 40.7 hours per week in paid employment and 11.0 hours per week in tele- work (26% of their total hours). The fact that respon- dents had been with their current organization for 11.5 years and in the current job for 5.5 years suggests that experienced professionals are more likely to be permit- ted to telework than are their more junior colleagues. The men in the sample differed from the women in a number of ways (see Table 1). The women in the sample were younger than the men and had spent fewer years working for their current employer. Also noteworthy are the data showing that the women in the sample spent more hours in childcare per week than their male colleagues and reported higher levels of work role overload and family role overload. The men in the sample, on the other hand, spend more hours per week in paid employment. These gender differences are consistent with those commonly reported in the lit- erature. There were no gender differences in time spent in telework per week and work role overload. 3.2. Procedure To conduct our analysis we tested for moderation and mediation using hierarchal regression analysis. The following outlines the procedure used for both tests. The test for moderation shows whether the mod- erator variable significantly influences the outcome variable beyond that of the predictor variable. To do this, the predictor and moderator variables should be centered and standardized to reduce problems asso- ciated with multicollinearity (i.e., high correlations) among the variables in the regression equation [56, 58]. A product term is used to establish the effect of the moderator variable beyond that of the predictor. To form the product term, we multiplied together the pre- dictor and moderator variables using the newly cen- tered and standardized terms [57]. If the product term is significant after controlling for predictor and moder- ator variables, than moderation exists. We conduct this analysis using hierarchal regression analysis. Three steps are used as outlined by Fraizer et al. [50]. Demographic variables are included in the first step to control for the influence of potential of con- founding variables. Predictor and moderator variables are included in the second step to account for individ- ual effects. Product terms are included in the final step to see whether the product term significantly accounts for variance beyond that of the individual contributions of predictor and moderator variables. To further interpret the moderating variable, many scholars chose to show the influence of the moderating variable through visual means. To do so one may fol- low the procedure recommended by Cohen et al. [55] and create two simple linear regressions of the pre- dictor variable (i.e., work role overload on hours in work per week) and plot the results. The plot shows two points along the X-axis: high (+1SD) and low (- 1SD) values of the predictor variable. It also shows two regression lines: high (+1SD) and low (-1SD) values of the moderating variable (i.e., hours in telework per week). If the test for moderation proved unsuccessful, it is possible that the telework variable is actually a me- diating variable. Testing for mediation explores the idea that the predictor variable influences a mediation variable which in turn influences an outcome variable. ences in tenure (operationalized as years in organiza- tion and years in job) because some researchers have suggested employees use telework arrangements as a way to "escape" organizational stress that has devel- oped over time [23]. Finally, our decision to control for time in eldercare per week is consistent with our decision to define family demands in terms of hours per week in childcare and the fact that relatively few respondents (25%) spent time each week in eldercare activities. Work Role Overload 3.4 3.3 3.2 3.1 3 2.9 2.8 2.7 2.6 2.5 Low Telework Hours High Telework Hours 4. Results To determine how the number of telework hours re- lates to work role overload and family role overload, we follow the test for moderation and mediation using hierarchical multiple regression analysis as outlined by Frazier et al. [55]. To compare our data to previous research, Table 2 presents means, standard deviations, and correlations for each of the measures. The signifi- cant correlation between work role overload and fam- ily role overload is consistent with what has been re- ported in the literature [1,2,4] and supports the idea that spillover occurs between work and family domains (i.e. people who are overwhelmed at work are likely to "bring it home" and vice versa). In support of Hypoth- esis 1 and 3, we find strong positive associations be- tween predictor and outcome variables within the work environment (i.e. hours in work per week and work role overload; B 0.247, p < 0.01) and the family envi- ronment (i.e. hours in childcare per week and family role overload; B = 0.321, p < 0.01). Strong support for these two hypotheses supports our decision to test the ability of hours per week in telework to moderate both of these relationships. = 4.1. Moderation We followed the procedures outlined by Frazier et al. [55] to test hypotheses 2 and 4 (i.e. number of hours in telework per week moderates the relation- ship between work/family demands and work/family overload). As shown in Table 3, Hypothesis 3, which posited that hours spent in telework per week (i.e. con- trol) would moderate the relationship between work demands (hours in work per week) and work role over- load, was supported (B = -0.040, p < 0.05). The R change associated with the interaction term was 0.003 (p < 0.05). - 1 SD (30.21 hrs) +1 SD (51.25 hrs) Employed Hours Fig. 1. The moderating role of hours in telework per week on the hours in work per week - work role overload relationship. Mean employed hours = 40.73. = To further interpret the interaction effect, we plot predicted values for the outcome variable (work role overload) for representative groups. As shown in Fig. 1, low hours in telework per week was associated with both the lowest levels of work role overload (Y = 2.75 when hours in work per week was low) and the high- est levels of work role overload (Y: 3.3 when hours in work per week was high). When hours per week in telework are high, on the other hand, work role over- load increases at a slower rate (i.e. values of Y = 2.85 for low hours in work per week and Y = 3.2 for high hours in work per week). These finding indicate that the control over work demands offered by telework be- come more important as hours spent in work week increase. per We also used hierarchical regression analysis used to test for a possible curvilinear relationship within our model. We tested for curvilinearity by computing a squared telework hour term and entering it in after the control and demographic variables. In the regression model, a curvilinear relationship is evident if the addi- tion of this quadratic term results in significant incre- mental variance after the linear effect has been taken into account [56]. As shown in Table 3, there was no significance in the squared term coefficient ( = 0, n.s.) and the model did not achieve a better fit with addition of this variable. This additional analysis pro- vides additional support for the linear model tested in this study. 1 An Excel file created to calculate these predicted values is avail- able from Linda Duxbury. Table 1 Gender differences Male Female Total Variable N M SD N M SD N M SD Age 712 46.71 10.62 1082 44.08 9.58 1794 45.12* 10.08 Years with org 715 13.63 50.00 1087 10.21 8.88 1802 11.57* 32.02 Years in job 714 6.37 6.75 1088 5.00 5.10 1802 5.54** 5.85 Eldercare hours 718 1.08 3.06 1088 1.93 6.20 1806 1.59** 5.21 Employed hours 717 43.03 11.25 1087 39.20 9.72 1804 40.73** 10.52 Telework hours 718 11.09 13.50 1088 11.00 12.39 1806 11.03 12.84 Childcare hours 718 8.64 12.22 1088 13.63 19.88 1806 11.65** 17.42 Work role overload 718 2.87 0.84 1088 3.13 0.88 1806 3.03 0.87 Family role overload 670 2.70 0.87 1018 3.07 0.92 1688 2.92* 0.92 p

Step by Step Solution

There are 3 Steps involved in it

Step: 1

Get Instant Access to Expert-Tailored Solutions

See step-by-step solutions with expert insights and AI powered tools for academic success

Step: 2

Step: 3

Ace Your Homework with AI

Get the answers you need in no time with our AI-driven, step-by-step assistance

Get Started