Although the implementation of banking services relies heavily on accounting, hardly any scholarly literature exists that explains in detail the accounting mechanics of bank credit creation and precisely how bank accounting differs from corporate accounting of non-bank firms. There is also virtually no scholarly literature on the question of which regulations precisely enable banks to create money. These issues are however of great interest, especially since the function of banks as the creators and allocators of the money supply is not explicitly stated in any law, statute, regulation, ordinance, directive or court judgment. From the absence of explicit statutory powers to create money it can be deduced that this ability of banks is likely derived from the operational, that is, accounting conventions and regulations of banking. These either differ from those of non-banks, so that only banks are able to create money, or else non-banks have missed out on the significant opportunities money creation may afford. In order to identify the difference in accounting treatment of the lending op()eration by banks, we adopt a comparative accounting analysis perspective. For this purpose, we compare the accounting of a loan extended by

(a) a non-financial corporation (NFC, such as a manufacturer extending a financial loan to a supplier),

(b) a non-bank financial institution (NBFI, such as a stock broker extending a margin loan to a client) and

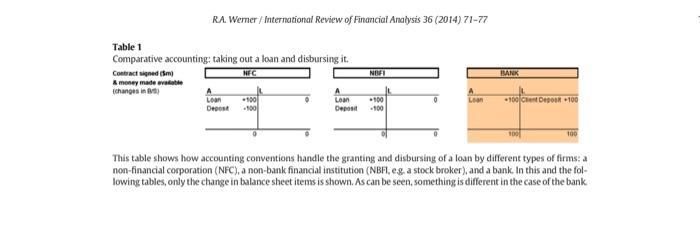

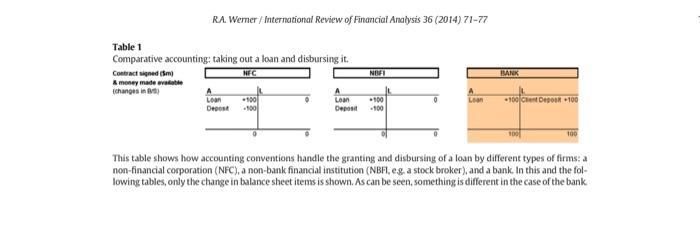

(c) a bank. Table 1 shows the changes in balance sheets of a new loan of $100 m, after its issuance and remittance.

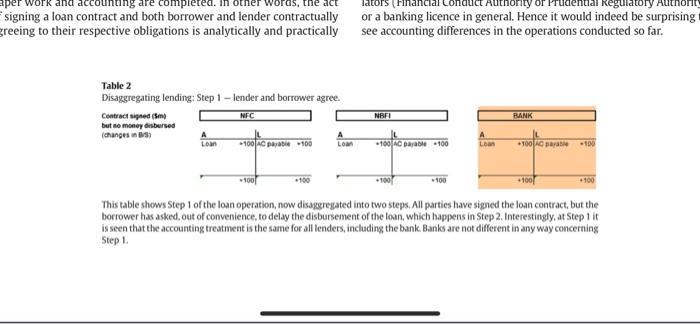

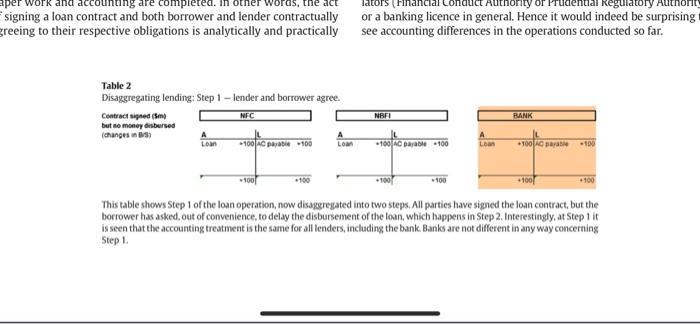

When the non-financial corporation, such as a manufacturer, grants a loan to another firm, the loan contract is shown as an increase in assets: the firm now has an additional claim on debtors — this is the borrower's promise to repay the loan. The lender purchases the loan contract, treated as a promissory note. Meanwhile, when the firm disburses the loan (and hence discharges its obligation to make the money available to the borrower), it is drawing down its cash reserves or monetary deposits with its banks. As a result, one gross asset increase is matched by an equally-sized gross asset decrease, leaving net total assets unchanged. In the second case, of a non-bank financial institution, such as a stock broker engaging in margin lending, the loan contract is the claim on the borrower that is added as an asset to the balance sheet, while the disbursement of the loan – for instance by transferring it to the client or the stock exchange to settle the margin trade conducted by its client – reduces the firm's monetary balances (likely held with a bank). As a result, total assets and total liabilities remain unchanged. While the balance sheet total is not affected by the granting and disbursement of the loan in the case of firms other than banks, the picture looks very different in the case of a bank. While the loan contract shows up as an increase in assets with all types of corporations, in the case of a bank the disbursement of the loan takes a different form from that of the other firms: it appears as a positive entry on the liability side of the balance sheet, as opposed to being a negative entry on the asset side, as in the case of non-banks. As a result, it does not counter-balance the increased gross assets. Instead, both assets and liabilities expand. The bank's balance sheet lengthens on both sides by the amount of the loan (see the empirical evidence in Werner, 2014a, 2014c). Thus it is clear that banks conduct their accounting operations differently from others, even differently from their near-relatives, the non-bank financial institutions. What precisely, however, causes this very different treatment of lending on bank balance sheets as opposed to its treatment by all other types of firms? In order to answer this question, the comparison of the above accounting information is insufficient. It is necessary to gain further, more detailed insight into the accounting operations shown in Table 1. Specifically, what is it that enables banks to discharge their loan without drawing down any assets (as both the financial intermediation and fractional reserve theories of banking had indeed maintained, erroneously)? In order to answer this question, the device is chosen to break down what currently is one set of double-entry operations, into smaller steps in order to be able to analyse them in greater detail. Specifically, the lending process is broken down into two steps, whose accounting representations are shown separately and in sequence. Assume, for instance, that the borrower asked out of convenience to proceed with signing the loan contract, but for the disbursement of the loan to be delayed by a week, while all other paper work and accounting are completed. In other words, the act of signing a loan contract and both borrower and lender contractually agreeing to their respective obligations is analytically and practically separated from the act of disbursing the loan and thereby the lender discharging the lender's obligation to pay out the funds. Step 1 shows the loan upon signing, committing both parties to their respective obligations (the bank to pay soon, the borrower to repay with interest much later). At this stage the loan funds are not yet made available by the lender. So the lender has an open liability, namely the disbursement of the loan to the borrower. In corporate accounting this is identified as a liability of the category ‘accounts payable’. (Step 2 will then describe the situation when the lender has in fact made the loan money available to the borrower and thus discharged the liability arising from its accounts payable item to the borrower.) Table 2 shows Step 1 of this disaggregated lending operation, by recording the changes in balance sheet items. The same operation is shown for the non-financial corporation, the non-bank financial institution and for the bank (Table 2). In all cases, in Step 1 the loan contract creates an asset for the lender, as the money will be repaid in the future, and a liability in the form of the ‘accounts payable’, as the loaned money will have to be made available to the borrower at some stage. Therefore, for all types of firms, including banks, the balance sheet lengthens, as both an asset and a liability is added to the balance sheet. What emerges is, therefore that, surprisingly, in Step 1, the accounting is identical for all types of firms, including the bank. In other words, whatever makes banks different and special from non-banks is not visible in the act of agreeing to and implementing a loan contract without disbursing it. Moreover, we see what lengthens the balance sheet of firms – any firm, not just banks – namely agreeing to lend money, while not (yet) paying out the funds to the borrower. That banks and non-banks are identical in their operations at this stage is an interesting finding. Upon reflection, it is not surprising, as it makes legal and regulatory sense: The act of granting a loan by one legal person to another is not a regulated activity. Business lending in the UK does not require authorisation of any supervisory or regulatory authority. Thus any firm can specialize in lending to other companies at interest, without requiring any authorisation from the financial regulators (Financial Conduct Authority or Prudential Regulatory Authority) or a banking licence in general. Hence it would indeed be surprising to see accounting differences in the operations conducted so far.