Question: After reading the article below identify and briefly discuss each of the following key takeaways key criticisms/oversights, how what youve read might be implemented into

After reading the article below identify and briefly discuss each of the following

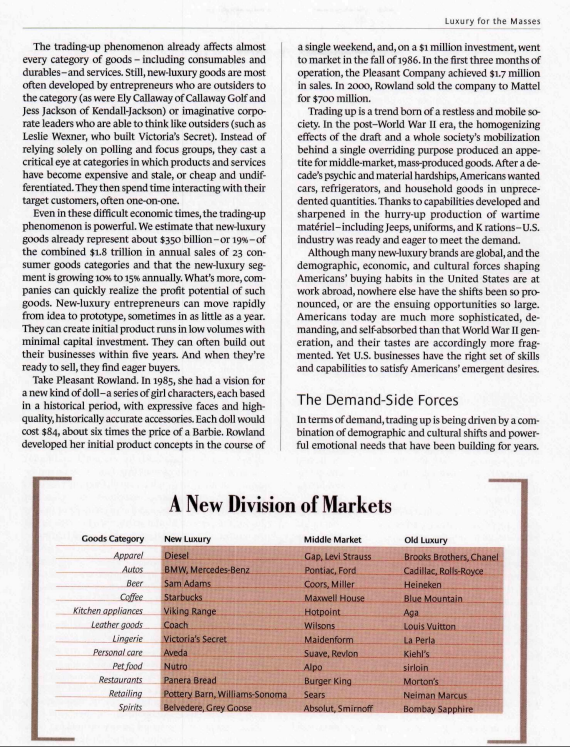

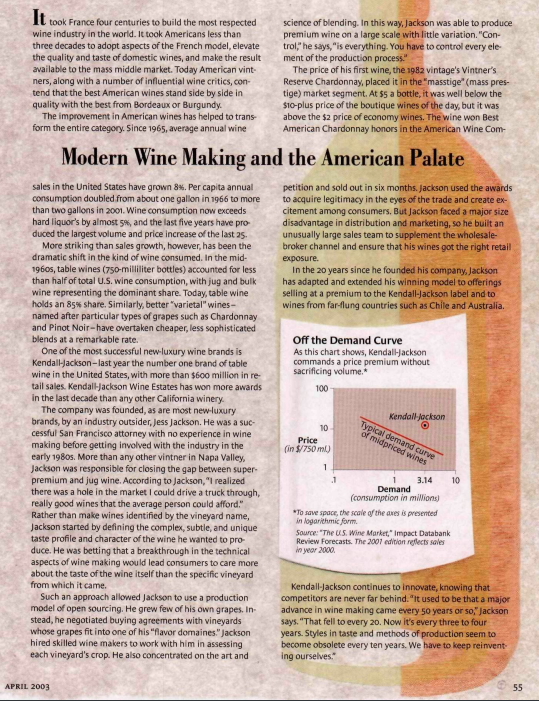

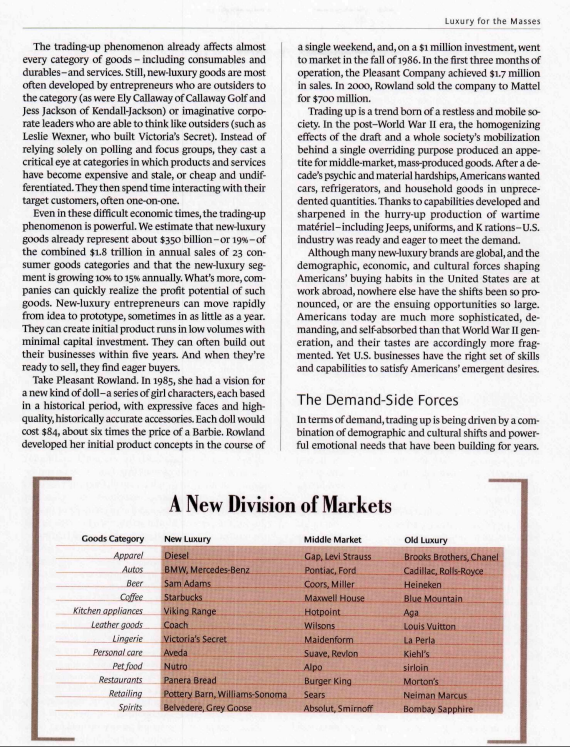

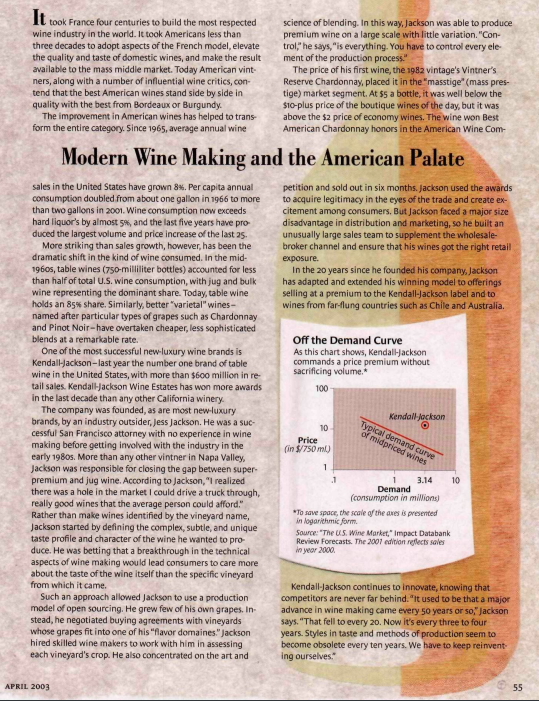

Middle-market consumers are trading up, going from Chevys to Beamers, from Bud to Sam Adams. Understanding their desires offers an immense opportunity for profit. A MERICA'S MIDDLE-MARKET consumers are trading up to higher levels of quality and taste. The members of the 47 million households that constitute the middle market (those earning $50,000 and above in annual income) are broadly edu- cated and well traveled as never before, and they have around $3.5 trillion of disposable income. As a result, they are willing to pay premiums of 20% to 200% for the kinds of well-designed, well-engineered, and well- crafted goods-often possessing the artisanal touches of traditional luxury goods-not before found in the mass middle market. Most important, even when they address basic necessities, such goods evoke and engage con- sumers' emotions while feeding their aspirations for a better life. We call these new-luxury goods. Unlike old- luxury goods, they can generate high volumes despite their relatively high prices. Businesses offer a wide variety of new-luxury prod- ucts and services - including automobiles; home fur- nishings; appliances; consumer electronics; shoes and other apparel; food; health, personal, and pet care; sports equipment; toys; and beer, wine, and spirits. Com- panies at the new-luxury forefront are achieving levels of profitability and growth beyond the reach of their conventional competitors. Consider, for example, Panera Bread, a bakery-caf chain that offers freshly made sandwiches with seasonal ingredients. Panera customers line up to spend around $6 for a chicken panini and share a meal with friends and colleagues in pleasant, comfortable surroundings. For the first three quarters of 2002, Panera's sales were 41% higher than they were for the same period of 2001. By contrast, sales at Burger King-where consumers pay about $3 for a chicken sandwich and sit on hard plastic chairs-were flat. At $750 million, Panera's projected U.S. sales for 2002 are only a fraction of Burger King's $8.5 bil- lion in U.S. sales that year, yet its market capitalization Luxury for the Masses is now about two-thirds of the $1.5 billion that Burger King was sold for that year. Companies have enjoyed similar results in three major types of new-luxury goods: Accessible Superpremium. These products are priced at or near the top of their category, but middle- market consumers can still afford them, primarily be- cause they are relatively low-ticket items. For example, Belvedere Vodka, which undergoes four rounds of dis- tillations for a smoother taste, is able to command about $28 a bottle, a 75% premium over Absolut at $16. Nutro pet food, which contains nutritious ingredients, sells at 71 cents a pound, a 58% premium over Alpo, which costs about 45 cents a pound. Starbucks, an iconic new-luxury brand, charges around $1.50 for a tall coffee, about a 40% premium over a similar-sized Dunkin' Donuts cup, which costs about $1.10. Old-Luxury Brand Extensions. These are lower-priced versions of goods that have traditionally been affordable only by the rich-households earning at least $200,000 annually. In 2002, unit sales of BMW 325 sedans-which consumers buy for their advanced technology, their work-hard, play-hard image, and the excitement of driv- ing them-were up 12% over 2001 levels. The Chevy Mal- ibu, by contrast, fails to offer any technological features its rivals lack, or to give drivers any special pleasure in driving or owning it - what might be called technical, functional, and emotional benefits, the three rungs of a product's ladder of benefits. Despite the Malibu's $19,000 list price, $10,000 less than the 325's, its sales were down 4% in 2002. In 2001, BMW-with total sales of 172,505 vehicles in the United States-achieved a greater profit worldwide, $2 billion, than any other carmaker. General Motors earned just $600 million on U.S. sales of more than 4 million vehicles; both Ford and Daimler- Chrysler suffered losses. Also on the list of old-luxury companies extending their brands are Mercedes-Benz, Ermenegildo Zegna, Tiffany, and Burberry, offering affordable products alongside their traditional ones. Mass Prestige or "Masstige." These goods occupy a sweet spot between mass and class. While commanding a premium over conventional products, they are priced well below superpremium or old-luxury goods. An eight- ounce bottle of Bath & Body Works body lotion, for ex- ample, sells for $9, or $1.13 per ounce. That's a premium. of 276 % over an 11-ounce bottle of Vaseline Intensive Care, which sells for $3.29, or 30 cents an ounce. But it is Michael L. Silverstein is a senior vice president at the far from being the highest-priced product in the cate- gory: An eight-ounce bottle of Kiehl's Creme de Corps, one of many superpremium skin creams, retails for $24, a 167 % premium over the Bath & Body Works prod- uct- and many brands cost considerably more. Coach similarly positions its leather goods at prices below. Gucci's, but well above those of Mossimo at Target. When a new-luxury brand takes hold, it can quickly change the rules of its category, achieve market leader- ship-as Starbucks coffee, Kendall-Jackson wines, and Victoria's Secret lingerie have-and force the price-volume demand curve to be redrawn. In laundry appliances, for example, conventional industry wisdom held that wash- ers and dryers could not appeal to consumers' emotions. People would therefore never pay more than $800 for the two. Then Whirlpool created the Duet, a front-loading washer/dryer set that costs around $2,100. Due in large When a new-luxury brand takes hold, it can quickly change the rules of its category and achieve market leadership. part to their European styling and speedier, gentler cy- cles, these machines have become immensely popular. Now Whirlpool cannot keep up with demand. As consumers shop more selectively, the categories new-luxury goods occupy tend to polarize. Consumers tend to trade up to the premium product in categories that are important to them but trade down-buying a low-cost brand or private label, or even going without- in categories that are less meaningful to them. Conse- quently, people's buying habits do not invariably corre- spond to their income level. They may shop at Costco but drive a Mercedes, or they may buy private-label dish- washing liquid but drink Sam Adams beer. Left in the cold are midpriced items that fail to distinguish them- selves on any of the three rungs of a product's ladder of benefits. Companies unable to match the prices of low-cost products or promise the emotional engage- ment of new-luxury goods face what we call death in the The trading-up phenomenon already affects almost every category of goods - including consumables and durables-and services. Still, new-luxury goods are most often developed by entrepreneurs who are outsiders to the category (as were Ely Callaway of Callaway Golf and Jess Jackson of Kendall-Jackson) or imaginative corpo- rate leaders who are able to think like outsiders (such as Leslie Wexner, who built Victoria's Secret). Instead of relying solely on polling and focus groups, they cast a critical eye at categories in which products and services have become expensive and stale, or cheap and undif- ferentiated. They then spend time interacting with their target customers, often one-on-one. Even in these difficult economic times, the trading-up phenomenon is powerful. We estimate that new-luxury goods already represent about $350 billion-or 19%-of the combined $1.8 trillion in annual sales of 23 con- sumer goods categories and that the new-luxury seg- ment is growing 10% to 15% annually. What's more, com- panies can quickly realize the profit potential of such goods. New-luxury entrepreneurs can move rapidly from idea to prototype, sometimes in as little as a year. They can create initial product runs in low volumes with minimal capital investment. They can often build out their businesses within five years. And when they're ready to sell, they find eager buyers. Take Pleasant Rowland. In 1985, she had a vision for a new kind of doll-a series of girl characters, each based in a historical period, with expressive faces and high- quality, historically accurate accessories. Each doll would cost $84, about six times the price of a Barbie. Rowland developed her initial product concepts in the course of Goods Category Apparel Autos Beer Coffee Kitchen appliances Leather goods Lingerie Personal care Pet food Restaurants Retailing Spirits Luxury for the Masses a single weekend, and, on a $1 million investment, went to market in the fall of 1986. In the first three months of operation, the Pleasant Company achieved $1.7 million in sales. In 2000, Rowland sold the company to Mattel for $700 million. Trading up is a trend born of a restless and mobile so- ciety. In the post-World War II era, the homogenizing effects of the draft and a whole society's mobilization behind a single overriding purpose produced an appe- tite for middle-market, mass-produced goods. After a de- cade's psychic and material hardships, Americans wanted cars, refrigerators, and household goods in unprece- dented quantities. Thanks to capabilities developed and sharpened in the hurry-up production of wartime matriel-including Jeeps, uniforms, and K rations-U.S. industry was ready and eager to meet the demand. Although many new-luxury brands are global, and the demographic, economic, and cultural forces shaping Americans' buying habits in the United States are at work abroad, nowhere else have the shifts been so pro- nounced, or are the ensuing opportunities so large. Americans today are much more sophisticated, de- manding, and self-absorbed than that World War II gen- eration, and their tastes are accordingly more frag- mented. Yet U.S. businesses have the right set of skills and capabilities to satisfy Americans' emergent desires. The Demand-Side Forces In terms of demand, trading up is being driven by a com- bination of demographic and cultural shifts and power- ful emotional needs that have been building for years. Old Luxury Brooks Brothers, Chanel Cadillac, Rolls-Royce Heineken Blue Mountain Aga Louis Vuitton La Perla Kiehl's sirloin Morton's Neiman Marcus Bombay Sapphire A New Division of Markets New Luxury Middle Market Diesel Gap, Levi Strauss BMW, Mercedes-Benz Pontiac, Ford Sam Adams Coors, Miller Starbucks Maxwell House Viking Range Hotpoint Coach Wilsons Victoria's Secret Maidenform Aveda Suave, Revlon Alpo Nutro Panera Bread Burger King Sears Pottery Barn, Williams-Sonoma Belvedere, Grey Goose Absolut, Smirnoff Luxury for the Masses. Access to Flexible Supply-Chain Networks and Global Resources. Companies of almost any size can take advantage of foreign labor markets and construct and manage complex global networks for sourcing, man- ufacturing, assembling, and distributing their goods. The reasons are twofold: International trade barriers have eased, and providers of global supply-chain-management services have emerged. Hong Kong-based Li & Fung has created the world's largest network of contract manu- facturers, operating in 40 countries. China has emerged New-luxury leaders have an abiding belief in the elasticity of demand. as a key player in that network. Direct manufacturing in- vestment there, combined with low wages, increasingly skilled labor and stricter quality control, has furthered companies' ability to deliver upscale goods at moder- ate prices. These supply-side factors make it possible for entre- preneurs and companies to raise capital to research, de- velop, and manufacture goods quickly as well as cost- effectively, and for companies to scale up volume when demand increases. The New Consumer's Needs Consumers have always had a love affair with products, but today they have more money, a greater desire to ex- amine their emotional side, a wider variety of choices in goods and services, and less guilt about spending. They seek goods that make positive statements about who they are and what they would like to be and that help them manage the stresses of everyday life. In the course of our research to better understand our clients and their needs, we defined the four "emotional pools" that most affect consumers' behavior, particu- larly in their encounters with new-luxury goods. The ap- peal of a given product can encompass more than one set of emotions. The first emotional pool, Taking Care of Me, involves overcoming the effects of too much work and too little time. Most working Americans-working women with families, in particular-are looking for ways to get a few moments alone, reward themselves after a tough day, rejuvenate the exhausted body, soothe the frayed emo- tions, and even restore the soul. They don't see the point of working hard and earning good money if they can't spend some of it on themselves. As one female con- sumer explained, "Women today think their mothers did not get to spend money on themselves because they were not earners, but they get to do that now. The fi- nancial independence of women leads to an 'I can buy it if I want to' attitude." Such consumers say that a $9 bottle of Aveda shampoo-with its all-natural formula, calming aroma, and environmentally friendly image - can make them feel refreshed, renewed, and good about themselves in ways that a lower-priced bottle of con- ventional shampoo cannot. Personal care items, bath and body products, spas, gourmet groceries and pre- pared foods, linens and bedding, and home electronics are important Taking Care of Me categories. The second pool, Questing, encompasses venturing out into the world, gaining new experiences, and over- coming personal limits. In the process, people learn new things, master new skills, and have fun. Accordingly, new- luxury consumers seek out experiences that challenge them and help define who they are in their own eyes and those of others. Travel, cars, sports equipment, din- ing out, computers, and wines are Questing categories. The third pool, Connecting, involves finding, build- ing, maintaining, and deepening relationships. Connect- ing includes three subpools: attracting mates, spending time with friends, and nurturing family members. Peo- ple connect by sharing a dinner out, using state-of-the- art kitchen appliances, exchanging gifts, and indulging in some types of travel such as cruises. The last pool, Individual Style, comes from using the sophistication and currency of one's consumer choices to demonstrate one's success in life and express one's individuality and personal values. It is often associated with Connecting, especially mating, because people choose particular goods to send signals to prospective partners about who they are and what they're looking for. A person's personal combination of choices can also create in him or her a sense of uniqueness. Apparel, fash- ion accessories, cars, spirits, and travel enable consumers to express their style, knowledge, taste, and values. The Practices of New-Luxury Leaders In every transformation of a category of goods we have studied, we can identify eight practices that new-luxury leaders follow: 1. Never underestimate the customer. Jess Jackson of Kendall-Jackson rightly believed he could convert middle-market wine drinkers into upscale wine drinkers, although no one had done it before. In the categories new-luxury consumers care about, they consider them- selves knowledgeable and even expert. These consumers It took France four centuries to build the most respected wine industry in the world. It took Americans less than three decades to adopt aspects of the French model, elevate the quality and taste of domestic wines, and make the result available to the mass middle market. Today American vint- ners, along with a number of influential wine critics, con- tend that the best American wines stand side by side in quality with the best from Bordeaux or Burgundy. The improvement in American wines has helped to trans- form the entire category. Since 1965, average annual wine Modern Wine Making and the American Palate sales in the United States have grown 8%. Per capita annual consumption doubled from about one gallon in 1966 to more than two gallons in 2001. Wine consumption now exceeds hard liquor's by almost 5%, and the last five years have pro duced the largest volume and price increase of the last 25. More striking than sales growth, however, has been the dramatic shift in the kind of wine consumed. In the mid- 1960s, table wines (750-milliliter bottles) accounted for less than half of total U.S. wine consumption, with jug and bulk wine representing the dominant share. Today, table wine holds an 85% share. Similarly, better "varietal" wines- named after particular types of grapes such as Chardonnay and Pinot Noir-have overtaken cheaper, less sophisticated blends at a remarkable rate. One of the most successful new-luxury wine brands is Kendall-jackson-last year the number one brand of table wine in the United States, with more than $600 million in re- tail sales. Kendall-jackson Wine Estates has won more awards in the last decade than any other California winery. The company was founded, as are most new-luxury brands, by an industry outsider, Jess Jackson. He was a suc- cessful San Francisco attorney with no experience in wine making before getting involved with the industry in the early 1980s. More than any other vintner in Napa Valley, Jackson was responsible for closing the gap between super- premium and jug wine. According to Jackson, "I realized there was a hole in the market I could drive a truck through, really good wines that the average person could afford." Rather than make wines identified by the vineyard name, Jackson started by defining the complex, subtle, and unique taste profile and character of the wine he wanted to pro- duce. He was betting that a breakthrough in the technical aspects of wine making would lead consumers to care more about the taste of the wine itself than the specific vineyard from which it came. Such an approach allowed Jackson to use a production model of open sourcing. He grew few of his own grapes. In- stead, he negotiated buying agreements with vineyards whose grapes fit into one of his "flavor domaines." Jackson hired skilled wine makers to work with him in assessing each vineyard's crop. He also concentrated on the art and APRIL 2003 science of blending. In this way, Jackson was able to produce premium wine on a large scale with little variation. "Con- trol," he says, "is everything. You have to control every ele ment of the production process." The price of his first wine, the 1982 vintage's Vintner's Reserve Chardonnay, placed it in the "masstige" (mass pres- tige) market segment. At $5 a bottle, it was well below the $10-plus price of the boutique wines of the day, but it was above the $2 price of economy wines. The wine won Best American Chardonnay honors in the American Wine Com- petition and sold out in six months. Jackson used the awards to acquire legitimacy in the eyes of the trade and create ex- citement among consumers. But Jackson faced a major size disadvantage in distribution and marketing, so he built an unusually large sales team to supplement the wholesale- broker channel and ensure that his wines got the right retail exposure. In the 20 years since he founded his company, Jackson has adapted and extended his winning model to offerings selling at a premium to the Kendall-Jackson label and to wines from far-flung countries such as Chile and Australia. Off the Demand Curve As this chart shows, Kendall-jackson commands a price premium without sacrificing volume.* 100 10 Price (in $/750ml) 1 Demand (consumption in millions) *To save space, the scale of the axes is presented in logarithmic form. Source: "The U.S. Wine Market," Impact Databank Review Forecasts. The 2001 edition reflects sales in year 2000. Kendall-Jackson continues to innovate, knowing that. competitors are never far behind. "It used to be that a major advance in wine making came every 50 years or so," Jackson says. "That fell to every 20. Now it's every three to four years. Styles in taste and methods of production seem to become obsolete every ten years. We have to keep reinvent ing ourselves." 55 Kendall-jackson Typical demand curve of midpriced wines 3.14 10 Luxury for the Masses appreciate quality, technological innovation, and an aura of authenticity. They care about brand heritage and keeping up with the product category as a whole. 2. Shatter the demand curve. Jackson redrew the demand curve for the wine industry. He saw the poten- tial to create a market segment in which higher prices and volumes would generate substantially greater prof- its. Leaders in all new-luxury categories seek to do as Kendall-Jackson did. Like Whirlpool's Duet, Sub-Zero disproved the conventional wisdom that no substantial market existed for household appliances above the $1,000 price point. New-luxury leaders have an abiding belief in the elasticity of demand-that it can be created in virtually any category by products that offer the right combination of consumer benefits. 3. Create a ladder of genuine benefits. As stated ear- lier, successful new-luxury goods connect with the con- sumer on three levels-technical, functional, and emo- tional. Jackson's breakthrough in the wine category, for example, was to create technical differences in grape se- lection and wine blending that produced genuine dif- ferences and improvements in taste. The ladder of bene- fits applies to all categories, even those in which it might seem improbable. Pet lovers, for example, buy gourmet pet food such as Nutro because it is technically different (with added nutrients and organic ingredients), func- tionally superior (its special formulas produce a shinier Consumers won't remain emotionally invested in a brand if its technical and functional benefits do not differentiate it from the pack. coat or a calmer disposition), and emotionally satisfy ing (owners feel they are taking exceptionally good care of a beloved family member). The compound annual growth rate for conventional pet food is 1% to 2%; it is 9% for premium and superpremium pet-food segments, which now account for almost one-third of the total pet- food market. 4. Escalate innovation and elevate quality. The mar- ket for new luxury is rich in opportunity, but it is also un- stable. That's because technical and functional advan- tages are increasingly short-lived, as new competitors enter the market and standardize innovations that were once the distinguishing features of high-priced goods. Nearly 80% of all cars come with standard features (anti- lock brakes and power door locks, for instance) that were exclusively luxury features only a few years ago. Consumers won't remain emotionally invested in a well- established brand if its technical and functional benefits do not differentiate it from the pack. Winners in new-luxury markets render their own products obsolete before a new competitor does it for them. These companies strive to shorten the develop- ment cycle, and they invest heavily in production im- provements, but they control only those elements of the supply chain that are critical to maintaining quality and preserving the heart of the brand. 5. Extend the brand's price range and positioning. Many new-luxury brands move upmarket to create as- pirational appeal and down-market to make their prod- ucts more accessible and competitive. A traditional com- petitor's highest price may be three to four times its lowest; for new-luxury players, it's often five to ten times. They are careful, however, to create, define, and maintain a distinct character and meaning for every level of their products, while ensuring that they all par- take of the brand essence. Every Mercedes model-from the C230 sports coup at $26,000 to the Maybach 62 at $350,000-shares in the brand themes of advanced en- gineering, quality manufacture, exemplary perfor- mance, solidity and safety, and luxurious comfort, and each has the distinctive Mercedes look and "badging." 6. Customize the value chain. Like Jess Jackson, Boston Beer founder Jim Koch emphasized control, rather than ownership, of the value chain and became a master at orchestrating it. Koch specified the process for making Sam Adams Boston Lager, which combined aspects of nineteenth-century brewing with twentieth- century methods of quality control. So, too, Koch se- lected the product's ingredients and managed distribu- tion. Without making its own hops or building its own production facilities, Boston Beer was able to grow in volume while also maintaining its reputation for well- crafted beer. 7. Use brand apostles. A small percentage of new- luxury consumers contribute the preponderance of profit in a given category. In categories marked by fre- quent repeat purchases, such as lingerie and spirits, 10% of customers typically generate up to half the sales and profits. Reaching those customers requires a different kind of launch, one involving carefully managed initial sales to carefully selected groups in a handful of venues. It also requires frequent feedback from early purchas- ers and word-of-mouth recommendations. Belvedere Vodka, for one, was launched at tasting events for bar- tenders. Gift bottles were also sent to key players in important markets. When introducing the Big Bertha driver, Ely Callaway understood that recreational golf- ers-many of whom are businesspeople - would take their cues from those using the new and unusual clubs. So he enlisted Bill Gates, among others, to appear in ads. An intense, continuing focus on these core customers will reveal early signs of a shifting market and produce ideas for next-generation features and products. 8. Attack the category like an outsider. Ely Callaway had a long career in textiles and then in wine before he entered the golf business at age 63. Pleasant Rowland was an educator and television reporter before she cre- ated American Girl dolls. An outsider mentality allows one to see the category without the baggage of precon- ceptions and to avoid making what others view as in- evitable compromises. People within new-luxury organizations think differ- ently from those working for conventional producers as well. Ellen Brothers, president of the Pleasant Company, says that the thinking of founder Pleasant Rowland still infuses the company. "If you ask any of our 1,200 em- ployees what business we are in," says Brothers, "no one will say, "The toy business' Every one of them will say, 'We're in the girl business." The Certainty of Change There remains vast potential to reshape categories, de- throne market leaders, create new winners, and prod growth and rebirth in mature industries. The transformation possibilities are almost infinite, especially for affordable superpremium goods that ap- peal to the trendy among us. Premium vodka has be- come the new single-malt scotch. What will the new DAN LI Luxury for the Masses vodka be? Managers of these brands must always be on the lookout for an ebbing of consumer interest, sudden shifts in taste, and the rise of a category transformer that may do to them what Belvedere and Grey Goose have done to Smirnoff and Absolut. The dual challenge for old-luxury brand extensions is to continually enhance the brand at the high end and avoid diluting its essence at the low end. Although masstige products in new categories have great potential, they can be attacked by products that offer similar benefits at a lower price or by premium products that deliver a greater number of genuine ben- efits for a small price increment. Every masstige product, therefore, is a candidate for death in the middle. Traditionally, consumers have gotten credit for keep- ing the engines of production rolling merely by buying in ever-greater quantities. Business got the credit for all the breakthroughs in technology, productivity, quality, and service. New-luxury consumers, however, are so knowledgeable, affluent, and selective that the classic distinction between enterprising producer and passive consumer has become obsolete. Businesses that have failed to note that the consumer has gotten smarter and more active need to get busy listening and respond- ing-on every level. 1. Our research includes work with clients over a period of ten years, a quan titative survey of 2,200 American consumers conducted in late 2002, analy sis of 30 categories, demographic data research, interviews with hundreds of consumers, interviews with many new-luxury leaders, and a literature review of 800 books, articles, and related materials. Reprint R0304C To order, see page 125. WHO'S NOT IN WHO'S WHO WHO'S WHO -SCHWADRA Middle-market consumers are trading up, going from Chevys to Beamers, from Bud to Sam Adams. Understanding their desires offers an immense opportunity for profit. A MERICA'S MIDDLE-MARKET consumers are trading up to higher levels of quality and taste. The members of the 47 million households that constitute the middle market (those earning $50,000 and above in annual income) are broadly edu- cated and well traveled as never before, and they have around $3.5 trillion of disposable income. As a result, they are willing to pay premiums of 20% to 200% for the kinds of well-designed, well-engineered, and well- crafted goods-often possessing the artisanal touches of traditional luxury goods-not before found in the mass middle market. Most important, even when they address basic necessities, such goods evoke and engage con- sumers' emotions while feeding their aspirations for a better life. We call these new-luxury goods. Unlike old- luxury goods, they can generate high volumes despite their relatively high prices. Businesses offer a wide variety of new-luxury prod- ucts and services - including automobiles; home fur- nishings; appliances; consumer electronics; shoes and other apparel; food; health, personal, and pet care; sports equipment; toys; and beer, wine, and spirits. Com- panies at the new-luxury forefront are achieving levels of profitability and growth beyond the reach of their conventional competitors. Consider, for example, Panera Bread, a bakery-caf chain that offers freshly made sandwiches with seasonal ingredients. Panera customers line up to spend around $6 for a chicken panini and share a meal with friends and colleagues in pleasant, comfortable surroundings. For the first three quarters of 2002, Panera's sales were 41% higher than they were for the same period of 2001. By contrast, sales at Burger King-where consumers pay about $3 for a chicken sandwich and sit on hard plastic chairs-were flat. At $750 million, Panera's projected U.S. sales for 2002 are only a fraction of Burger King's $8.5 bil- lion in U.S. sales that year, yet its market capitalization Luxury for the Masses is now about two-thirds of the $1.5 billion that Burger King was sold for that year. Companies have enjoyed similar results in three major types of new-luxury goods: Accessible Superpremium. These products are priced at or near the top of their category, but middle- market consumers can still afford them, primarily be- cause they are relatively low-ticket items. For example, Belvedere Vodka, which undergoes four rounds of dis- tillations for a smoother taste, is able to command about $28 a bottle, a 75% premium over Absolut at $16. Nutro pet food, which contains nutritious ingredients, sells at 71 cents a pound, a 58% premium over Alpo, which costs about 45 cents a pound. Starbucks, an iconic new-luxury brand, charges around $1.50 for a tall coffee, about a 40% premium over a similar-sized Dunkin' Donuts cup, which costs about $1.10. Old-Luxury Brand Extensions. These are lower-priced versions of goods that have traditionally been affordable only by the rich-households earning at least $200,000 annually. In 2002, unit sales of BMW 325 sedans-which consumers buy for their advanced technology, their work-hard, play-hard image, and the excitement of driv- ing them-were up 12% over 2001 levels. The Chevy Mal- ibu, by contrast, fails to offer any technological features its rivals lack, or to give drivers any special pleasure in driving or owning it - what might be called technical, functional, and emotional benefits, the three rungs of a product's ladder of benefits. Despite the Malibu's $19,000 list price, $10,000 less than the 325's, its sales were down 4% in 2002. In 2001, BMW-with total sales of 172,505 vehicles in the United States-achieved a greater profit worldwide, $2 billion, than any other carmaker. General Motors earned just $600 million on U.S. sales of more than 4 million vehicles; both Ford and Daimler- Chrysler suffered losses. Also on the list of old-luxury companies extending their brands are Mercedes-Benz, Ermenegildo Zegna, Tiffany, and Burberry, offering affordable products alongside their traditional ones. Mass Prestige or "Masstige." These goods occupy a sweet spot between mass and class. While commanding a premium over conventional products, they are priced well below superpremium or old-luxury goods. An eight- ounce bottle of Bath & Body Works body lotion, for ex- ample, sells for $9, or $1.13 per ounce. That's a premium. of 276 % over an 11-ounce bottle of Vaseline Intensive Care, which sells for $3.29, or 30 cents an ounce. But it is Michael L. Silverstein is a senior vice president at the far from being the highest-priced product in the cate- gory: An eight-ounce bottle of Kiehl's Creme de Corps, one of many superpremium skin creams, retails for $24, a 167 % premium over the Bath & Body Works prod- uct- and many brands cost considerably more. Coach similarly positions its leather goods at prices below. Gucci's, but well above those of Mossimo at Target. When a new-luxury brand takes hold, it can quickly change the rules of its category, achieve market leader- ship-as Starbucks coffee, Kendall-Jackson wines, and Victoria's Secret lingerie have-and force the price-volume demand curve to be redrawn. In laundry appliances, for example, conventional industry wisdom held that wash- ers and dryers could not appeal to consumers' emotions. People would therefore never pay more than $800 for the two. Then Whirlpool created the Duet, a front-loading washer/dryer set that costs around $2,100. Due in large When a new-luxury brand takes hold, it can quickly change the rules of its category and achieve market leadership. part to their European styling and speedier, gentler cy- cles, these machines have become immensely popular. Now Whirlpool cannot keep up with demand. As consumers shop more selectively, the categories new-luxury goods occupy tend to polarize. Consumers tend to trade up to the premium product in categories that are important to them but trade down-buying a low-cost brand or private label, or even going without- in categories that are less meaningful to them. Conse- quently, people's buying habits do not invariably corre- spond to their income level. They may shop at Costco but drive a Mercedes, or they may buy private-label dish- washing liquid but drink Sam Adams beer. Left in the cold are midpriced items that fail to distinguish them- selves on any of the three rungs of a product's ladder of benefits. Companies unable to match the prices of low-cost products or promise the emotional engage- ment of new-luxury goods face what we call death in the The trading-up phenomenon already affects almost every category of goods - including consumables and durables-and services. Still, new-luxury goods are most often developed by entrepreneurs who are outsiders to the category (as were Ely Callaway of Callaway Golf and Jess Jackson of Kendall-Jackson) or imaginative corpo- rate leaders who are able to think like outsiders (such as Leslie Wexner, who built Victoria's Secret). Instead of relying solely on polling and focus groups, they cast a critical eye at categories in which products and services have become expensive and stale, or cheap and undif- ferentiated. They then spend time interacting with their target customers, often one-on-one. Even in these difficult economic times, the trading-up phenomenon is powerful. We estimate that new-luxury goods already represent about $350 billion-or 19%-of the combined $1.8 trillion in annual sales of 23 con- sumer goods categories and that the new-luxury seg- ment is growing 10% to 15% annually. What's more, com- panies can quickly realize the profit potential of such goods. New-luxury entrepreneurs can move rapidly from idea to prototype, sometimes in as little as a year. They can create initial product runs in low volumes with minimal capital investment. They can often build out their businesses within five years. And when they're ready to sell, they find eager buyers. Take Pleasant Rowland. In 1985, she had a vision for a new kind of doll-a series of girl characters, each based in a historical period, with expressive faces and high- quality, historically accurate accessories. Each doll would cost $84, about six times the price of a Barbie. Rowland developed her initial product concepts in the course of Goods Category Apparel Autos Beer Coffee Kitchen appliances Leather goods Lingerie Personal care Pet food Restaurants Retailing Spirits Luxury for the Masses a single weekend, and, on a $1 million investment, went to market in the fall of 1986. In the first three months of operation, the Pleasant Company achieved $1.7 million in sales. In 2000, Rowland sold the company to Mattel for $700 million. Trading up is a trend born of a restless and mobile so- ciety. In the post-World War II era, the homogenizing effects of the draft and a whole society's mobilization behind a single overriding purpose produced an appe- tite for middle-market, mass-produced goods. After a de- cade's psychic and material hardships, Americans wanted cars, refrigerators, and household goods in unprece- dented quantities. Thanks to capabilities developed and sharpened in the hurry-up production of wartime matriel-including Jeeps, uniforms, and K rations-U.S. industry was ready and eager to meet the demand. Although many new-luxury brands are global, and the demographic, economic, and cultural forces shaping Americans' buying habits in the United States are at work abroad, nowhere else have the shifts been so pro- nounced, or are the ensuing opportunities so large. Americans today are much more sophisticated, de- manding, and self-absorbed than that World War II gen- eration, and their tastes are accordingly more frag- mented. Yet U.S. businesses have the right set of skills and capabilities to satisfy Americans' emergent desires. The Demand-Side Forces In terms of demand, trading up is being driven by a com- bination of demographic and cultural shifts and power- ful emotional needs that have been building for years. Old Luxury Brooks Brothers, Chanel Cadillac, Rolls-Royce Heineken Blue Mountain Aga Louis Vuitton La Perla Kiehl's sirloin Morton's Neiman Marcus Bombay Sapphire A New Division of Markets New Luxury Middle Market Diesel Gap, Levi Strauss BMW, Mercedes-Benz Pontiac, Ford Sam Adams Coors, Miller Starbucks Maxwell House Viking Range Hotpoint Coach Wilsons Victoria's Secret Maidenform Aveda Suave, Revlon Alpo Nutro Panera Bread Burger King Sears Pottery Barn, Williams-Sonoma Belvedere, Grey Goose Absolut, Smirnoff Luxury for the Masses. Access to Flexible Supply-Chain Networks and Global Resources. Companies of almost any size can take advantage of foreign labor markets and construct and manage complex global networks for sourcing, man- ufacturing, assembling, and distributing their goods. The reasons are twofold: International trade barriers have eased, and providers of global supply-chain-management services have emerged. Hong Kong-based Li & Fung has created the world's largest network of contract manu- facturers, operating in 40 countries. China has emerged New-luxury leaders have an abiding belief in the elasticity of demand. as a key player in that network. Direct manufacturing in- vestment there, combined with low wages, increasingly skilled labor and stricter quality control, has furthered companies' ability to deliver upscale goods at moder- ate prices. These supply-side factors make it possible for entre- preneurs and companies to raise capital to research, de- velop, and manufacture goods quickly as well as cost- effectively, and for companies to scale up volume when demand increases. The New Consumer's Needs Consumers have always had a love affair with products, but today they have more money, a greater desire to ex- amine their emotional side, a wider variety of choices in goods and services, and less guilt about spending. They seek goods that make positive statements about who they are and what they would like to be and that help them manage the stresses of everyday life. In the course of our research to better understand our clients and their needs, we defined the four "emotional pools" that most affect consumers' behavior, particu- larly in their encounters with new-luxury goods. The ap- peal of a given product can encompass more than one set of emotions. The first emotional pool, Taking Care of Me, involves overcoming the effects of too much work and too little time. Most working Americans-working women with families, in particular-are looking for ways to get a few moments alone, reward themselves after a tough day, rejuvenate the exhausted body, soothe the frayed emo- tions, and even restore the soul. They don't see the point of working hard and earning good money if they can't spend some of it on themselves. As one female con- sumer explained, "Women today think their mothers did not get to spend money on themselves because they were not earners, but they get to do that now. The fi- nancial independence of women leads to an 'I can buy it if I want to' attitude." Such consumers say that a $9 bottle of Aveda shampoo-with its all-natural formula, calming aroma, and environmentally friendly image - can make them feel refreshed, renewed, and good about themselves in ways that a lower-priced bottle of con- ventional shampoo cannot. Personal care items, bath and body products, spas, gourmet groceries and pre- pared foods, linens and bedding, and home electronics are important Taking Care of Me categories. The second pool, Questing, encompasses venturing out into the world, gaining new experiences, and over- coming personal limits. In the process, people learn new things, master new skills, and have fun. Accordingly, new- luxury consumers seek out experiences that challenge them and help define who they are in their own eyes and those of others. Travel, cars, sports equipment, din- ing out, computers, and wines are Questing categories. The third pool, Connecting, involves finding, build- ing, maintaining, and deepening relationships. Connect- ing includes three subpools: attracting mates, spending time with friends, and nurturing family members. Peo- ple connect by sharing a dinner out, using state-of-the- art kitchen appliances, exchanging gifts, and indulging in some types of travel such as cruises. The last pool, Individual Style, comes from using the sophistication and currency of one's consumer choices to demonstrate one's success in life and express one's individuality and personal values. It is often associated with Connecting, especially mating, because people choose particular goods to send signals to prospective partners about who they are and what they're looking for. A person's personal combination of choices can also create in him or her a sense of uniqueness. Apparel, fash- ion accessories, cars, spirits, and travel enable consumers to express their style, knowledge, taste, and values. The Practices of New-Luxury Leaders In every transformation of a category of goods we have studied, we can identify eight practices that new-luxury leaders follow: 1. Never underestimate the customer. Jess Jackson of Kendall-Jackson rightly believed he could convert middle-market wine drinkers into upscale wine drinkers, although no one had done it before. In the categories new-luxury consumers care about, they consider them- selves knowledgeable and even expert. These consumers It took France four centuries to build the most respected wine industry in the world. It took Americans less than three decades to adopt aspects of the French model, elevate the quality and taste of domestic wines, and make the result available to the mass middle market. Today American vint- ners, along with a number of influential wine critics, con- tend that the best American wines stand side by side in quality with the best from Bordeaux or Burgundy. The improvement in American wines has helped to trans- form the entire category. Since 1965, average annual wine Modern Wine Making and the American Palate sales in the United States have grown 8%. Per capita annual consumption doubled from about one gallon in 1966 to more than two gallons in 2001. Wine consumption now exceeds hard liquor's by almost 5%, and the last five years have pro duced the largest volume and price increase of the last 25. More striking than sales growth, however, has been the dramatic shift in the kind of wine consumed. In the mid- 1960s, table wines (750-milliliter bottles) accounted for less than half of total U.S. wine consumption, with jug and bulk wine representing the dominant share. Today, table wine holds an 85% share. Similarly, better "varietal" wines- named after particular types of grapes such as Chardonnay and Pinot Noir-have overtaken cheaper, less sophisticated blends at a remarkable rate. One of the most successful new-luxury wine brands is Kendall-jackson-last year the number one brand of table wine in the United States, with more than $600 million in re- tail sales. Kendall-jackson Wine Estates has won more awards in the last decade than any other California winery. The company was founded, as are most new-luxury brands, by an industry outsider, Jess Jackson. He was a suc- cessful San Francisco attorney with no experience in wine making before getting involved with the industry in the early 1980s. More than any other vintner in Napa Valley, Jackson was responsible for closing the gap between super- premium and jug wine. According to Jackson, "I realized there was a hole in the market I could drive a truck through, really good wines that the average person could afford." Rather than make wines identified by the vineyard name, Jackson started by defining the complex, subtle, and unique taste profile and character of the wine he wanted to pro- duce. He was betting that a breakthrough in the technical aspects of wine making would lead consumers to care more about the taste of the wine itself than the specific vineyard from which it came. Such an approach allowed Jackson to use a production model of open sourcing. He grew few of his own grapes. In- stead, he negotiated buying agreements with vineyards whose grapes fit into one of his "flavor domaines." Jackson hired skilled wine makers to work with him in assessing each vineyard's crop. He also concentrated on the art and APRIL 2003 science of blending. In this way, Jackson was able to produce premium wine on a large scale with little variation. "Con- trol," he says, "is everything. You have to control every ele ment of the production process." The price of his first wine, the 1982 vintage's Vintner's Reserve Chardonnay, placed it in the "masstige" (mass pres- tige) market segment. At $5 a bottle, it was well below the $10-plus price of the boutique wines of the day, but it was above the $2 price of economy wines. The wine won Best American Chardonnay honors in the American Wine Com- petition and sold out in six months. Jackson used the awards to acquire legitimacy in the eyes of the trade and create ex- citement among consumers. But Jackson faced a major size disadvantage in distribution and marketing, so he built an unusually large sales team to supplement the wholesale- broker channel and ensure that his wines got the right retail exposure. In the 20 years since he founded his company, Jackson has adapted and extended his winning model to offerings selling at a premium to the Kendall-Jackson label and to wines from far-flung countries such as Chile and Australia. Off the Demand Curve As this chart shows, Kendall-jackson commands a price premium without sacrificing volume.* 100 10 Price (in $/750ml) 1 Demand (consumption in millions) *To save space, the scale of the axes is presented in logarithmic form. Source: "The U.S. Wine Market," Impact Databank Review Forecasts. The 2001 edition reflects sales in year 2000. Kendall-Jackson continues to innovate, knowing that. competitors are never far behind. "It used to be that a major advance in wine making came every 50 years or so," Jackson says. "That fell to every 20. Now it's every three to four years. Styles in taste and methods of production seem to become obsolete every ten years. We have to keep reinvent ing ourselves." 55 Kendall-jackson Typical demand curve of midpriced wines 3.14 10 Luxury for the Masses appreciate quality, technological innovation, and an aura of authenticity. They care about brand heritage and keeping up with the product category as a whole. 2. Shatter the demand curve. Jackson redrew the demand curve for the wine industry. He saw the poten- tial to create a market segment in which higher prices and volumes would generate substantially greater prof- its. Leaders in all new-luxury categories seek to do as Kendall-Jackson did. Like Whirlpool's Duet, Sub-Zero disproved the conventional wisdom that no substantial market existed for household appliances above the $1,000 price point. New-luxury leaders have an abiding belief in the elasticity of demand-that it can be created in virtually any category by products that offer the right combination of consumer benefits. 3. Create a ladder of genuine benefits. As stated ear- lier, successful new-luxury goods connect with the con- sumer on three levels-technical, functional, and emo- tional. Jackson's breakthrough in the wine category, for example, was to create technical differences in grape se- lection and wine blending that produced genuine dif- ferences and improvements in taste. The ladder of bene- fits applies to all categories, even those in which it might seem improbable. Pet lovers, for example, buy gourmet pet food such as Nutro because it is technically different (with added nutrients and organic ingredients), func- tionally superior (its special formulas produce a shinier Consumers won't remain emotionally invested in a brand if its technical and functional benefits do not differentiate it from the pack. coat or a calmer disposition), and emotionally satisfy ing (owners feel they are taking exceptionally good care of a beloved family member). The compound annual growth rate for conventional pet food is 1% to 2%; it is 9% for premium and superpremium pet-food segments, which now account for almost one-third of the total pet- food market. 4. Escalate innovation and elevate quality. The mar- ket for new luxury is rich in opportunity, but it is also un- stable. That's because technical and functional advan- tages are increasingly short-lived, as new competitors enter the market and standardize innovations that were once the distinguishing features of high-priced goods. Nearly 80% of all cars come with standard features (anti- lock brakes and power door locks, for instance) that were exclusively luxury features only a few years ago. Consumers won't remain emotionally invested in a well- established brand if its technical and functional benefits do not differentiate it from the pack. Winners in new-luxury markets render their own products obsolete before a new competitor does it for them. These companies strive to shorten the develop- ment cycle, and they invest heavily in production im- provements, but they control only those elements of the supply chain that are critical to maintaining quality and preserving the heart of the brand. 5. Extend the brand's price range and positioning. Many new-luxury brands move upmarket to create as- pirational appeal and down-market to make their prod- ucts more accessible and competitive. A traditional com- petitor's highest price may be three to four times its lowest; for new-luxury players, it's often five to ten times. They are careful, however, to create, define, and maintain a distinct character and meaning for every level of their products, while ensuring that they all par- take of the brand essence. Every Mercedes model-from the C230 sports coup at $26,000 to the Maybach 62 at $350,000-shares in the brand themes of advanced en- gineering, quality manufacture, exemplary perfor- mance, solidity and safety, and luxurious comfort, and each has the distinctive Mercedes look and "badging." 6. Customize the value chain. Like Jess Jackson, Boston Beer founder Jim Koch emphasized control, rather than ownership, of the value chain and became a master at orchestrating it. Koch specified the process for making Sam Adams Boston Lager, which combined aspects of nineteenth-century brewing with twentieth- century methods of quality control. So, too, Koch se- lected the product's ingredients and managed distribu- tion. Without making its own hops or building its own production facilities, Boston Beer was able to grow in volume while also maintaining its reputation for well- crafted beer. 7. Use brand apostles. A small percentage of new- luxury consumers contribute the preponderance of profit in a given category. In categories marked by fre- quent repeat purchases, such as lingerie and spirits, 10% of customers typically generate up to half the sales and profits. Reaching those customers requires a different kind of launch, one involving carefully managed initial sales to carefully selected groups in a handful of venues. It also requires frequent feedback from early purchas- ers and word-of-mouth recommendations. Belvedere Vodka, for one, was launched at tasting events for bar- tenders. Gift bottles were also sent to key players in important markets. When introducing the Big Bertha driver, Ely Callaway understood that recreational golf- ers-many of whom are businesspeople - would take their cues from those using the new and unusual clubs. So he enlisted Bill Gates, among others, to appear in ads. An intense, continuing focus on these core customers will reveal early signs of a shifting market and produce ideas for next-generation features and products. 8. Attack the category like an outsider. Ely Callaway had a long career in textiles and then in wine before he entered the golf business at age 63. Pleasant Rowland was an educator and television reporter before she cre- ated American Girl dolls. An outsider mentality allows one to see the category without the baggage of precon- ceptions and to avoid making what others view as in- evitable compromises. People within new-luxury organizations think differ- ently from those working for conventional producers as well. Ellen Brothers, president of the Pleasant Company, says that the thinking of founder Pleasant Rowland still infuses the company. "If you ask any of our 1,200 em- ployees what business we are in," says Brothers, "no one will say, "The toy business' Every one of them will say, 'We're in the girl business." The Certainty of Change There remains vast potential to reshape categories, de- throne market leaders, create new winners, and prod growth and rebirth in mature industries. The transformation possibilities are almost infinite, especially for affordable superpremium goods that ap- peal to the trendy among us. Premium vodka has be- come the new single-malt scotch. What will the new DAN LI Luxury for the Masses vodka be? Managers of these brands must always be on the lookout for an ebbing of consumer interest, sudden shifts in taste, and the rise of a category transformer that may do to them what Belvedere and Grey Goose have done to Smirnoff and Absolut. The dual challenge for old-luxury brand extensions is to continually enhance the brand at the high end and avoid diluting its essence at the low end. Although masstige products in new categories have great potential, they can be attacked by products that offer similar benefits at a lower price or by premium products that deliver a greater number of genuine ben- efits for a small price increment. Every masstige product, therefore, is a candidate for death in the middle. Traditionally, consumers have gotten credit for keep- ing the engines of production rolling merely by buying in ever-greater quantities. Business got the credit for all the breakthroughs in technology, productivity, quality, and service. New-luxury consumers, however, are so knowledgeable, affluent, and selective that the classic distinction between enterprising producer and passive consumer has become obsolete. Businesses that have failed to note that the consumer has gotten smarter and more active need to get busy listening and respond- ing-on every level. 1. Our research includes work with clients over a period of ten years, a quan titative survey of 2,200 American consumers conducted in late 2002, analy sis of 30 categories, demographic data research, interviews with hundreds of consumers, interviews with many new-luxury leaders, and a literature review of 800 books, articles, and related materials. Reprint R0304C To order, see page 125. WHO'S NOT IN WHO'S WHO WHO'S WHO -SCHWADRA