An important example to help tell the story of sport finance entails the World Cup. The World Cup, similar to the Olympics, is held every

An important example to help tell the story of sport finance entails the World Cup. The World Cup, similar to the Olympics, is held every four years, and the process to win the rights to host the games has become very competitive and shrouded in controversy. The issue of FIFA (Fdration Internationale de Football Association) corruption reached a crescendo with sponsors and others in 2015 when FIFA's president for the prior 17 years, Sepp Blatter, resigned. He resigned several days after seven soccer officials were arrested and held for extradition to the United States on corruption charges (Borden, Schmidt, & Apuzzojune, 2105). The scandal embroiled numerous individuals and helped show how money had greased the wheels of awarding the World Cup games. While the scandal, and resulting criminal convictions, resignation of Blatter, and significant negative publicity ruled the news cycle, soccer games were still played and a large amount of money was earned. This case study will explore some of the financial issues associated with the World Cup and also how financial issues affect a major soccer organization sending its athletes to the World Cup. FIFA has complete control over the World Cup because it is its event. FIFA's guide for the World Cup states,

FIFA is the original owner of all of the rights emanating from the FIFA World Cup? and any other related events coming under its jurisdiction, without any restrictions as to content, time, place and law. These rights include, among others, all kinds of financial rights, audiovisual and radio recording, reproduction and broadcasting rights, multimedia rights, marketing and promotional rights and incorporeal rights (such as those pertaining to emblems) as well as rights arising under copyright law whether currently existing or created in the future subject to any provision as set forth in specific regulations (FIFA 2014, p. 24).

In terms of revenue from preliminary matches, FIFA allows each host organization to collect revenue from ticket sales and commercial rights (broadcasting). From this amount, FIFA takes a levy of 2% of the gross revenue and allows host organizations to deduct up to 30% for renting stadiums and paying all applicable taxes. Besides those deductions, remaining funds, if any, are used to cover costs. The following guidelines spell out what expenses should be covered by whom:

- The visiting association shall cover its delegation's own international travel costs to the venue or the nearest airport, boarding, lodging, and incidental expenses.

- The host association shall cover domestic transport costs for the visiting team's official delegation.

- The host association shall also pay for first-class boarding and lodging and domestic transportation in the host country for the match officials, the match commissioner, the referee assessor, and any other FIFA officials (security officer, media officer, etc.) (FIFA, 2014).

For the World Cup, in contrast to qualifying events, FIFA pays certain amounts such as appropriate airfare to the games (based on FIFA's official airline sponsor charge; if a team wants to charter a flight, FIFA would pay the comparable rate for 50 tickets on its sponsor airline), hotel accommodations for five days before a team's first match through two days after the team's last match (for up to 50 people), match officials, winner awards, doping tests, and FIFA-associated insurance (FIFA, 2014). This does not include FIFA's costs for sending its own employees and stakeholders to the games.

One interesting element of FIFA's money distribution process is paying current and former professional teams for releasing players to play for the World Cup. FIFA set aside $70 million to distribute at a rate of $2,800 per player on World Cup duty per day. This money is shared among each player's current club and any other club the player had played for in the two previous years while engaged in qualification matches (Associated Press, 2014). Professional teams appreciate the payment, but they have significant risk if they release a player to play. If a player were to be injured, it could be a significant loss for a team. Of course, the team and the player would buy insurance, but soccer players can be very expensive. Heading into the 2014 World Cup, the Spanish squad was worth an estimated $921 million, almost $90 million more than Germany, which ended up winning the 2014 World Cup (Soergel, 2014).

The following paragraphs highlight some of the unique financial issues faced by some of the past and future World Cup hosts.

2014 World Cup

The 2014 World Cup was supposed to help Brazil shine on the international stage before hosting the 2016 Summer Olympics. The country was initially anticipating spending approximately $1 trillion on 12 stadiums and numerous infrastructure-related projects (Zimbalist, 2011). Brazil's projected budget for hosting the World Cup was initially estimated at $13.3 billion (compared with $18 billion for the Olympics). Such a huge budget for putting on the month-long tournament with 32 teams might seem like a great capital (long-term) investment for the host country. However, history has shown that the World Cup only generates approximately $3.5 billion in revenue (with most of the funds going to FIFA) (Zimbalist, 2011).

2018 World Cup

Russia hosted the 2018 World Cup and has increased government spending on the tournament by 19.1 billion rubles ($325 million). That additional amount announced in February 2017 brings the total projected government spending to 638.8 billion rubles (US$10.8 billion). All the increases were from federal budget funds, which resulted in almost 55% of the World Cup's total spending being funded by the Russian federal government (Associated Press, 2017).

These huge capital expenditures represent a significant expenditure to host the games, but they do not reflect the macro expenditures associated with a team.

2022 World Cup

The tiny oil-rich country of Qatar is set to host the 2022 World Cup. It initially was planning on spending $200 billion for the games, including $140 billion for transportation infrastructure (including a new airport, roads, and a metropolitan transit system) and $20 billion for tourism infrastructure. The award was controversial based on the country's size, population, and the summer heat, which exceeds 40C (104F) in the desert country (Associated Press, 2013). By 2017, Qatar was facing financial hardships (similar to Brazil) and was trying to slash its World Cup budget by 40% to 50% and was trying to reduce the number of stadiums from the planned 12 to 8 (Alkhalisi, 2017). These expenses are on top of the reported $17.2 billion spent on deals to help land the games, such as legitimate deals to purchase airplanes from France and numerous other questionable deals that purportedly paid decision makers millions of English pounds (Harris, 2015).

2026 World Cup

In 2017, FIFA announced that it would expand the World Cup field from 32 teams to 48 teams. This would increase the number of games played from 64 to 80. Besides the extra cost and possible extra revenue from increasing the tournament size, social media jumped on one aspect of the games?the popular Panini sticker albums produced for each World Cup. With the larger number of teams, it was estimated that collecting all the players from the 50-pence (US$0.65) packets (which have random stickers inserted) would probably cost a fan close to 500 pounds (US$656) (Curtis, 2017).

National Organizations Facing Financial Issues Such As Player Salaries

Besides the individual World Cup host- related expenses, other issues can include the individual costs associated with teams preparing for the games. For example, how much does it cost to house and train a team for several years? In addition to housing and meals, expenses include salaries for players, coaches, athletic trainers, nutritionists, sport psychologists, administrators, video recorders, travel coordinators, and numerous other individuals. Each team also plays a number of events in preparation for the World Cup such as exhibition games called friendlies and other events that can generate revenue from ticket sales and broadcast rights. These events also generate costs such as renting a large stadium, personnel, and administrative and marketing expenses.

Players' salaries can spark a controversy. There is one controversy associated with how much star players should receive compared with small role players. But another major controversy is how much female players should earn compared with male players. This controversy spun into a major lawsuit when some of the 2015 Women's World Cup Championship team members filed a complaint in the United States claiming wage discrimination since they earned less than the male athletes who did not do nearly as well. The salary information comparing some of the top U.S. players showed the following:

- Clint Dempsey pocketed almost $200,000 more than Carli Lloyd ($428,022-$240,019).

- Goaltender Tim Howard earned $398,495 while Hope Solo earned only $240,019.

- The men's team shared qualifying bonuses totaling $2 million while the women's bonus was only $300,000. While the men played more games (16 qualifying games compared with 5 for the women) that is still a difference of $125,000 per game vs. $60,000 per game.

- For being named to the final 23-player World Cup roster, the men received $55,000 each while the women earned $15,000 each.

- The women's national team flew economy class for most of its trips while the men flew only business class.

- For friendly matches, the men earned a salary of between $7,500 and $14,100 per win (based on their opponent's FIFA ranking), between $5,000 and $6,500 for draws, and $4,000 for a loss. The women earned $1,350 for each friendly win, draw, or loss.

- The men earned bonus money for every World Cup group stage point they earned and $5,500 for each group-stage match for which the players were rostered. The women were not lucky enough to earn any such bonuses (Davis, 2016).

These differences apply to money earned in the United States or for games under the auspices of the United States Soccer Federation (USSF). While at first it appears glaringly like discrimination and unfair payment based on gender, the complaint was filed in the United States and USSF could not be responsible for what FIFA paid out, which creates an even larger disparity. The men's prize money (for losing in the round of 16) was $9 million. This is $7 million more than the $2 million the women received as a team for winning the entire tournament (Davis, 2016). FIFA lets national soccer federations determine how to reward their players, and Germany, which won in 2014, distributed its $35 million victor purse by paying each player on the team a ?300,000 (US$408,000) bonus (AP, 2014).

It should be noted that FIFA generated $4.8 billion in revenue from the 2014 World Cup while the women's revenue was significantly less (Davis, 2016). In fact, the 2011 Women's World Cup (hosted in Germany) generated $72,818,500. In contrast, the 2010 men's South Africa World Cup generated over $3.7 billion, which is 50 times greater than the women. Women also received 10% of revenue in prize money in 2011 while the men only received 7% of the revenue they generated. The difference could also be seen with attendance. In 2014, attendance in Brazil averaged 53,592 for the men's games, while the women's attendance in Canada averaged only 26,029 fans (Pfeiffer, 2015).

Additional Costs

Another issue beyond hosting the games is the cost associated with bidding for a game, even if the city is not finally chosen. These costs can run into the millions. These costs include putting together a plan, bringing in consultants and lobbyists, producing high-end videos and brochures promoting the region, bringing in investment bankers to help explore stadium funding options, and hosting various dignitaries and showing them the best of the area (five-star hotels and top dining options). Olympic bids are similar to World Cup bids. In fact, in a bid to host Olympic Games, cities such as Chicago spent over $100 million in a failed attempt to host the 2012 Olympics, and Tokyo spent $150 million in its failed bid to host the 2016 Olympic Games (Zimbalist, 2016). One of the more publicized failed World Cup bids was undertaken by England to host the 2018 event. England spent over 19 million on the bid and lost in the first round of bidding?only garnering 2 of 22 votes ("Dave Richards sorry for comments about Fifa and Uefa," 2012).

Political cronies can benefit from hosting or even bidding on a major event, but others can also profit. When South Africa hosted the World Cup in 2010, some major construction companies were the big winners. The five primary construction companies saw their profits rise from $25 million in 2004 to $200 million in 2009?a major World Cup bounce for them (Zimbalist, 2016).

United States Soccer Federation Budget

The U.S. men's soccer team lost in the round of 16 during the 2014 World Cup. The women's team won the 2015 World Cup. How did this translate to revenue and expenses for the USSF, which is the governing body of soccer in the United States? To answer this question, one would have to examine the three primary areas where they generate both revenue and expenses: the nonnational team, the men's team, and the women's team. Thus, the 2016 nonnational team budget called for a surplus of $4,488,547 based on projected revenue of $67,444,188 and expenses of $62,955,641. The projections were for over $69 million in revenue, and they were able to reduce expenses to around $60 million, which would produce a variance (difference between what was budgeted for and the final projected amount) of a positive $4.6 million.

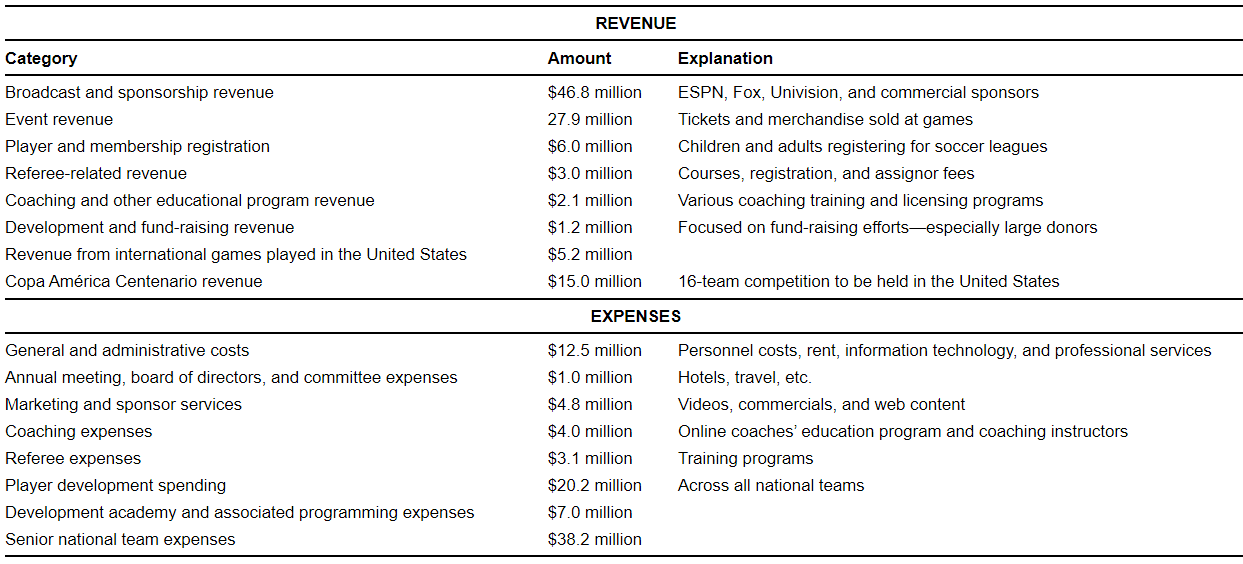

The men's national team was budgeted to bring in $23,817,500, but the team was expected to cost $27,118,386 for a $3.3 million loss. However, revenue jumped almost $21 million more than projected. While revenue shot up, so did expenses, which increased $6.7 million. The result was an almost $11 million profit (a $14 million swing from the budgeted amount) for the men's team. The positive financials did not translate to the women's team, which was budgeted for a $1.6 million loss (based on budgeted revenue of $3,234,600 and expenses of $4,843,190). The projected revenue was almost at the revenue mark, but the expenses jumped almost $600,000, so the final projected loss from the women's team was $2.2 million. The result was an $18 million variance from the budget and a positive $17.7 million year for USSF. For the 2017 fiscal year (April 2016-March 2017), total revenue and expected expenses could be grouped in eight categories (see table 1).

The budget was broken down even further through national men's and women's events scheduled for the 2017 fiscal year. For the women, as an example, there were three friendlies scheduled where ticket prices were scheduled to average $44. It was estimated that 17,000 tickets would be sold, generating $750,000. After deducting $286,500 in event expenses and $111,900 in team expenses, USSF was anticipating a net profit of $351,000.

Besides looking at the possible revenue and direct game expenses, there are numerous other administrative expenses (salaries, benefits, medical care, nutritionists, etc.). For example, the May and January training camps cost $244,000 to run. Even the cost to go to the Olympics needed to be calculated. Because the women's team was supposed to do very well, six games were estimated. The International Olympic Committee (IOC) was supposed to pay the team $250,000. The cost to send the women's team to the Olympics was $2.1 million. Thus, the glory of trying to win the gold (the U.S. team lost in the quarterfinals) cost the USSF around $1.857 million. Part of this money was to be earned back in a post-Olympic, 10-game, victory tour that didn't happen Tickets were to be sold

Table 1 2017 Fiscal Year (April 2016-March 2017) Revenue and Expenses

Category Broadcast and sponsorship revenue Event revenue Player and membership registration Referee-related revenue Coaching and other educational program revenue Development and fund-raising revenue Revenue from international games played in the United States Copa Amrica Centenario revenue General and administrative costs Annual meeting, board of directors, and committee expenses Marketing and sponsor services Coaching expenses Referee expenses Player development spending Development academy and associated programming expenses Senior national team expenses REVENUE Amount $46.8 million 27.9 million $6.0 million $3.0 million $2.1 million $1.2 million $5.2 million $15.0 million EXPENSES Explanation ESPN, Fox, Univision, and commercial sponsors Tickets and merchandise sold at games Children and adults registering for soccer leagues Courses, registration, and assignor fees Various coaching training and licensing programs Focused on fund-raising efforts-especially large donors 16-team competition to be held in the United States Personnel costs, rent, information technology, and professional services Hotels, travel, etc. Videos, commercials, and web content $12.5 million $1.0 million $4.8 million $4.0 million $3.1 million Online coaches' education program and coaching instructors Training programs $20.2 million $7.0 million $38.2 million Across all national teams

Step by Step Solution

There are 3 Steps involved in it

Step: 1

See step-by-step solutions with expert insights and AI powered tools for academic success

Step: 2

Step: 3

Ace Your Homework with AI

Get the answers you need in no time with our AI-driven, step-by-step assistance

Get Started