Answer Doc for 2 looks like this below

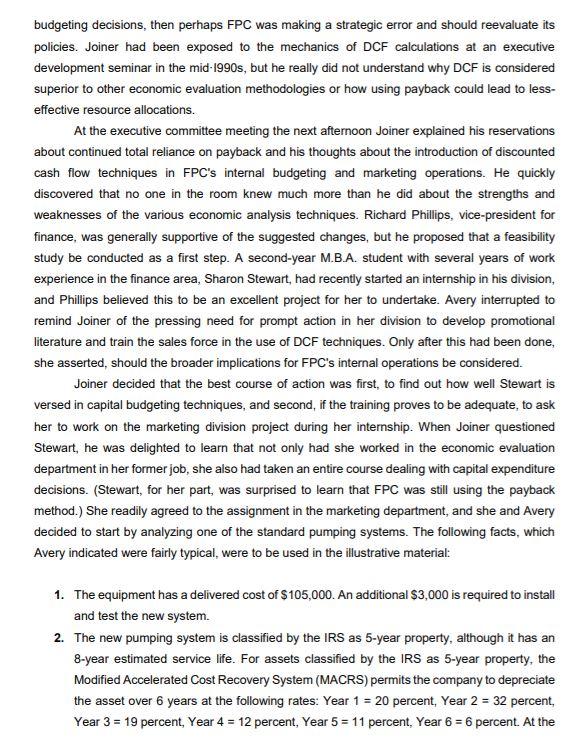

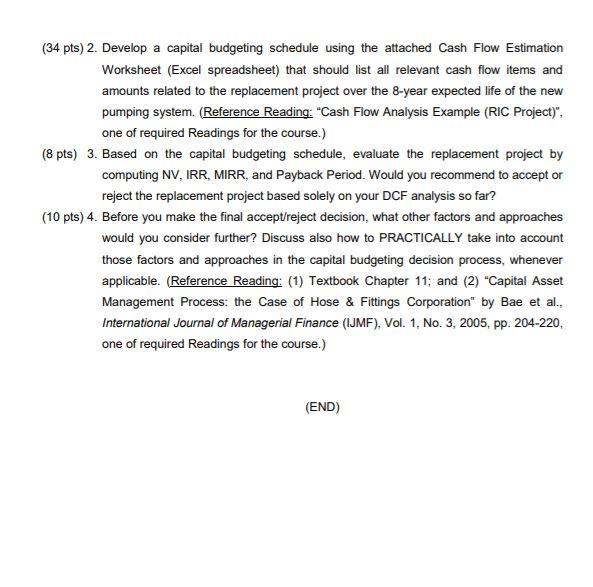

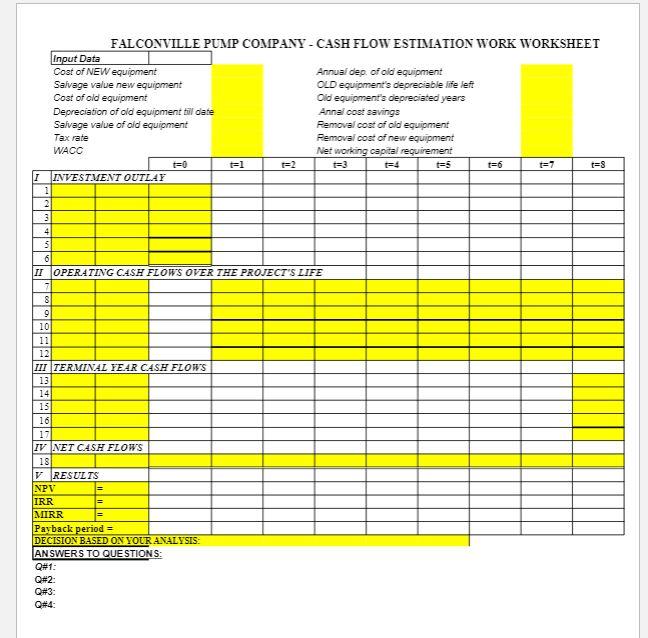

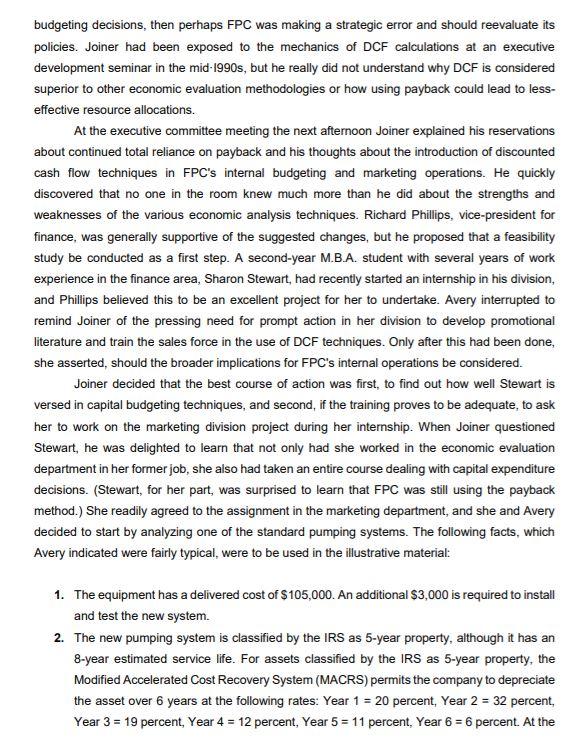

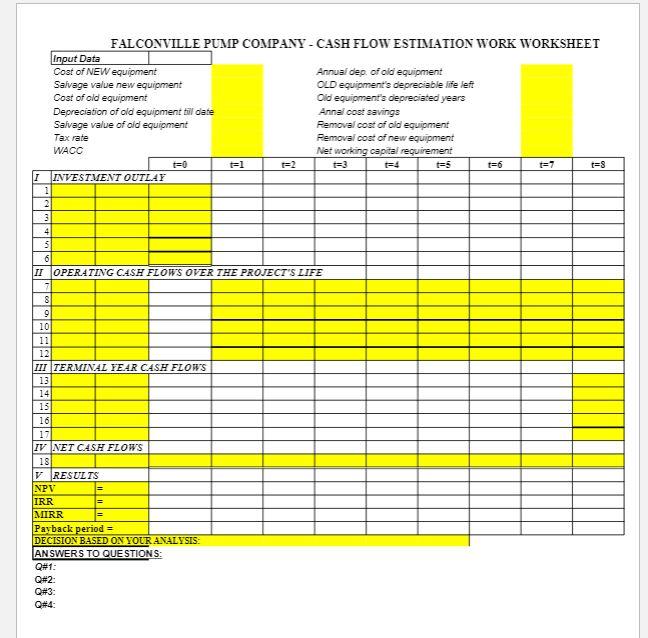

Case: Replacement Decisions Falconville Pump Company, Inc. Brandon Joiner, president and chief executive officer of Falconville Pump Company, Inc., has a potentially serious problem on his hands. The earnings of the firm were essentially flat in 2015 in spite of a general upturn in the industry. Now, well into the fourth quarter of 2016, the picture is even gloomier. FPC's performance has continued to deteriorate and, for the first time since 2000, a loss was incurred in the third quarter. Unless things improve quickly, it is possible that the company will show a loss for 2016 as a whole. This problem is particularly frustrating to Joiner because it comes on the heels of a report in one of the leading trade journals that rated FPCs products as superior to those of all competitors in the industry in terms of durability and customer service. Falconville Pump Company is a major producer of deep-well submersible pumps for commercial applications, irrigation equipment, and liquid distribution systems. Originally the company specialized in agricultural systems requiring large pumping volumes and high lift (wells over 500 feet deep), but that segment of the business represents less than 10 percent of total sales today. Most of the sales volume for the past five years has been in the areas of sanitation control systems, chemical and petroleum production, industrial process cooling systems, and pipeline transportation systems. Although most of the systems are specifically designed for individual customers, they tend to be constructed from standard modules that can be produced in volume to realize substantial economies of scale. These systems generally sell in the price range $50,000-$300,000, although it is not unusual to find contracts for several million dollars in pipeline transportation systems. Historically, most of FPCs sales have been to companies who were expanding their operations and therefore needed additional capacity. Recently, though, economic uncertainties have caused the firms to be more cautious in increasing their capacity, and, although interest rates have fallen substantially, there is a reluctance to assume greater levels of debt for risky expansion projects. Because of these trends, FPCs major sales target has shifted to retrofitting and upgrading existing plant and equipment Although the original agricultural product line of the company was based on technology that was substantially more advanced than usually encountered in the industry, the selling skills required to tailor the equipment to the job were no greater than for other manufacturers. Over the years, though, the degree of technological sophistication of the various products increased markedly so that today a high degree of technical expertise is required to match the appropriate equipment modules with a particular application. Consequently, the FPC sales force tends to be dominated by engineers or persons with at least some engineering background. The sales force works closely with potential customers to demonstrate the advantages of using Falconville Pump Company equipment. Since most sales involve a number of separate components or complete systems, the total dollar volume that can be generated from a single order makes it well worthwhile for the salespersons to devote considerable time and effort to closing each sale. The immediate cause of Joiner's preoccupation was a report he had received that afternoon from Janet Avery, the recently appointed vice-president for marketing. In an attempt to discover the causes of the firm's sagging sales and to identify ways to turn them around, Avery had prepared an in-depth analysis of business conditions in the industry and changes in the competitive positions of the leading firms-including Falconville Pump Company. Industry sales had been growing slowly for the past four years. In 2013 and 2014, FPC experienced a growth rate that was slightly higher than average, but since that time, they have not kept pace with the leaders. Hence, several firms were found to be increasing their share of the market at the expense of FPC. On the basis of her analysis, Avery concluded that the primary cause of the market share erosion the firm is now experiencing is the change in profile characteristics of the target market, along with FPC's failure to adapt its marketing strategy to reflect new environmental conditions. Up to now, Falconville Pump Company's marketing strategy has focused only on the engineering aspects of the products, and the firm's promotional literature reflects this orientation. Such an emphasis is considered to be appropriate for two reasons. First, engineering excellence has always been the hallmark of FPC. The rating of the company's products as most durable in the industry reflects this attention to technical details. Second, the primary customer contacts are the design engineers who must integrate the FPC equipment into larger systems. In the past, these individuals have always been inclined to focus their attention on technical specifications of the pumping equipment, so promotional literature is designed to answer the most frequently asked questions. This marketing strategy worked well until the late 2000s or early 2010s, partly because expenditures on pumping equipment for new facilities tend to be a very small fraction of the total capital outlay for the larger project and therefore, are not usually subjected to a separate rigorous analysis, and partly because capital was readily available at reasonable rates to finance the purchases. As interest rates started to rise dramatically toward the end of 2009, however, the sales force found it increasingly difficult to convince customers to buy FPC equipment solely on the basis of engineering performance characteristics. Increasingly, economic aspects of the proposed purchase have begun to dominate the sales effort. As customers' expansion plans were scaled back, the pumping equipment was no longer looked upon as only a small piece of a much larger project. Rather, prospective purchasers started to view expenditures on pumping equipment as involving, in their own right, a significant commitment of scarce and expensive capital resources. In more and more situations, the new equipment would replace an existing pumping system that was still serviceable, so FPC salespersons were compelled to demonstrate that the economic benefits from replacing the equipment immediately would more than offset the capital cost. By not recognizing the implications of this fundamental shift in the requirements for effective selling in a different target market and then adapting the marketing strategy and promotional material accordingly better to support the sales force, FPC placed itself at a competitive disadvantage. Other companies were quick to seize and exploit the opportunity, and, particularly in the past two years, they succeeded in taking customers away from Falconville Pump Company. Avery uncovered two additional pieces of information that both she and Joiner believed to be of particular significance. First, the companies that appeared to be gaining market share at FPC's expense stressed to the greatest extent the economics of replacement decisions in their promotional literature and sales presentations. All of them used a discounted cash flow (DCF) approach to convince potential customers of the advantages of replacing old pumping systems with the new high-efficiency models. Second, the most successful of FPC's salespersons in the past four years were engineers who had received formal college training in engineering economics. These individuals, who were trained in the use of DCF methodology, had employed their knowledge to refine their own sales approach and develop supplemental material. By doing so, they were able to generate substantially more sales than their untrained peers. Because of these facts, Avery concluded that as soon as possible, Falconville Pump Company should develop appropriate promotional literature and train all its sales force in the use of discounted cash flow project evaluation techniques. Joiner admitted that this appeared to be a sound recommendation, and he saw no reason why it should not be implemented immediately. As he pondered the information in Avery's report, though, he had the uneasy feeling that the implications of the decision were far more pervasive than they appeared to be on the surface. DCF techniques had never been used at Falconville Pump Company for any purpose, the payback method being the preferred tool for capital expenditure analysis. The more Joiner reflected on Avery's report, though, the more he started to question whether this was a wise policy. FPC's customers included some of the largest and best-run companies in the world. If they required an economic analysis based on discounted cash flow methodology tor their own capital budgeting decisions, then perhaps FPC was making a strategic error and should reevaluate its policies. Joiner had been exposed to the mechanics of DCF calculations at an executive development seminar in the mid-1990s, but he really did not understand why DCF is considered superior to other economic evaluation methodologies or how using payback could lead to less- effective resource allocations. At the executive committee meeting the next afternoon Joiner explained his reservations about continued total reliance on payback and his thoughts about the introduction of discounted cash flow techniques in FPC's internal budgeting and marketing operations. He quickly discovered that no one in the room knew much more than he did about the strengths and weaknesses of the various economic analysis techniques. Richard Phillips, vice-president for finance, was generally supportive of the suggested changes, but he proposed that a feasibility study be conducted as a first step. A second-year M.B.A. student with several years of work experience in the finance area, Sharon Stewart, had recently started an internship in his division, and Phillips believed this to be an excellent project for her to undertake. Avery interrupted to remind Joiner of the pressing need for prompt action in her division to develop promotional literature and train the sales force in the use of DCF techniques. Only after this had been done, she asserted, should the broader implications for FPC's internal operations be considered. Joiner decided that the best course of action was first, to find out how well Stewart is versed in capital budgeting techniques, and second, if the training proves to be adequate, to ask her to work on the marketing division project during her internship. When Joiner questioned Stewart, he was delighted to learn that not only had she worked in the economic evaluation department in her former job, she also had taken an entire course dealing with capital expenditure decisions. (Stewart, for her part, was surprised to learn that FPC was still using the payback method.) She readily agreed to the assignment in the marketing department, and she and Avery decided to start by analyzing one of the standard pumping systems. The following facts, which Avery indicated were fairly typical, were to be used in the illustrative material: 1. The equipment has a delivered cost of $105,000. An additional $3,000 is required to install and test the new system 2. The new pumping system is classified by the IRS as 5-year property, although it has an 8-year estimated service life. For assets classified by the IRS as 5-year property, the Modified Accelerated Cost Recovery System (MACRS) permits the company to depreciate the asset over 6 years at the following rates: Year 1 = 20 percent, Year 2 = 32 percent, Year 3 = 19 percent, Year 4 = 12 percent, Year 5 = 11 percent, Year 6 = 6 percent. At the end of 8 years, the salvage value is expected to be around 5 percent of the original purchase price, so the best estimate of salvage value at the end of the equipment's service life is $5,300, with removal costs of $1,200. 3. The existing pumping system was purchased at $45,000 eight years ago and has been depreciated on a straight-line basis over its economic life of 10 years. If the existing system is removed from the well and crated for pickup, it can be sold for $3,500 before tax. It will cost $1,000 to remove the system and crate it. 4. At the time of replacement, the firm will need to increase its net working capital requirements by $4,500 to support inventories. 5. The new pumping system offers lower maintenance costs and frees personnel who would otherwise have to monitor the system. In addition, it reduces product wastage because of a higher cooling efficiency. In total, it is estimated that the yearly savings will amount to $25,000 if the new pumping system is used. 6. The firm has its target debt ratio of 30 percent, and its cost of new debt is 10 percent. Its expected dividend per share next year, Ds, is $2.00 with a future growth rate of 6 percent per year. The firm's current stock price, Po, is $40.00. The firm uses its overall weighted average cost of capital in evaluating average risk projects, and the replacement project is perceived to be of average risk. 7. The firm's federal-plus-state tax rate is 30 percent, and this rate is projected to remain fairly constant into the future. QUESTIONS (Please show all your work either through Excel formulas/equations on the Cash Flow Estimation Worksheet or in separate tables at the bottom of your spreadsheet, whenever applicable. NO WORK SHOWN, NO POINTS.) (8 pts) 1. Compute the firm's weighted average cost of capital given the info/data in the case. What other approaches/methods can be used to measure the firm's cost of equity and thus its WACC? To that end, what additional info/data would you need? (Hint: A firm's weighted average cost of capital is equal to Ka = Wa(Ka) 1 - t) + WeKe, where Wa and We are the weights of debt and equity in the capital structure; K and K, are the respective costs of debt and equity; and t is the corporate tax rate; Do no round up your WACC figure.) (34 pts) 2. Develop a capital budgeting schedule using the attached Cash Flow Estimation Worksheet (Excel spreadsheet) that should list all relevant cash flow items and amounts related to the replacement project over the 8-year expected life of the new pumping system. (Reference Reading: "Cash Flow Analysis Example (RIC Project)", one of required Readings for the course.) (8 pts) 3. Based on the capital budgeting schedule, evaluate the replacement project by computing NV, IRR, MIRR, and Payback Period. Would you recommend to accept or reject the replacement project based solely on your DCF analysis so far? (10 pts) 4. Before you make the final accept/reject decision, what other factors and approaches would you consider further? Discuss also how to PRACTICALLY take into account those factors and approaches in the capital budgeting decision process, whenever applicable. (Reference Reading: (1) Textbook Chapter 11; and (2) "Capital Asset Management Process: the Case of Hose & Fittings Corporation" by Bae et al., International Journal of Managerial Finance (IJMF), Vol. 1, No. 3, 2005, pp. 204-220, one of required Readings for the course.) (END) FALCONVILLE PUMP COMPANY - CASH FLOW ESTIMATION WORK WORKSHEET Input Data Cost of NEW equipment Annual dep. of old equipment Salvage value new equipment OLD equipment's depreciable life left Coat of old equipment Olid equipment's depreciated years Depreciation of old equipment till dete Annal cost savings Salvage value of old equipment Removal cost of old equipment Tax rate Removal cost of new equipment WACC Networking capital requirement =0 =1 3 t=5 t=6 t=8 INVESTMENT OUTLAY 1 2 3 t=2 3 I 5 6 II OPERATING CASH FLOWS OVER THE PROJECT'S LIFE 7 8 9 10 11 12 III TERMINAL FEAR CASH FLOWS 13 14 15 16 17 IV NET CASH FLOWS 18 V RESULTS NPV IRR MIRR Payback period = DECISION BASED ON YOUR ANALYSIS: ANSWERS TO QUESTIONS: Q#1: Q#2: Q#3: Q#4 Case: Replacement Decisions Falconville Pump Company, Inc. Brandon Joiner, president and chief executive officer of Falconville Pump Company, Inc., has a potentially serious problem on his hands. The earnings of the firm were essentially flat in 2015 in spite of a general upturn in the industry. Now, well into the fourth quarter of 2016, the picture is even gloomier. FPC's performance has continued to deteriorate and, for the first time since 2000, a loss was incurred in the third quarter. Unless things improve quickly, it is possible that the company will show a loss for 2016 as a whole. This problem is particularly frustrating to Joiner because it comes on the heels of a report in one of the leading trade journals that rated FPCs products as superior to those of all competitors in the industry in terms of durability and customer service. Falconville Pump Company is a major producer of deep-well submersible pumps for commercial applications, irrigation equipment, and liquid distribution systems. Originally the company specialized in agricultural systems requiring large pumping volumes and high lift (wells over 500 feet deep), but that segment of the business represents less than 10 percent of total sales today. Most of the sales volume for the past five years has been in the areas of sanitation control systems, chemical and petroleum production, industrial process cooling systems, and pipeline transportation systems. Although most of the systems are specifically designed for individual customers, they tend to be constructed from standard modules that can be produced in volume to realize substantial economies of scale. These systems generally sell in the price range $50,000-$300,000, although it is not unusual to find contracts for several million dollars in pipeline transportation systems. Historically, most of FPCs sales have been to companies who were expanding their operations and therefore needed additional capacity. Recently, though, economic uncertainties have caused the firms to be more cautious in increasing their capacity, and, although interest rates have fallen substantially, there is a reluctance to assume greater levels of debt for risky expansion projects. Because of these trends, FPCs major sales target has shifted to retrofitting and upgrading existing plant and equipment Although the original agricultural product line of the company was based on technology that was substantially more advanced than usually encountered in the industry, the selling skills required to tailor the equipment to the job were no greater than for other manufacturers. Over the years, though, the degree of technological sophistication of the various products increased markedly so that today a high degree of technical expertise is required to match the appropriate equipment modules with a particular application. Consequently, the FPC sales force tends to be dominated by engineers or persons with at least some engineering background. The sales force works closely with potential customers to demonstrate the advantages of using Falconville Pump Company equipment. Since most sales involve a number of separate components or complete systems, the total dollar volume that can be generated from a single order makes it well worthwhile for the salespersons to devote considerable time and effort to closing each sale. The immediate cause of Joiner's preoccupation was a report he had received that afternoon from Janet Avery, the recently appointed vice-president for marketing. In an attempt to discover the causes of the firm's sagging sales and to identify ways to turn them around, Avery had prepared an in-depth analysis of business conditions in the industry and changes in the competitive positions of the leading firms-including Falconville Pump Company. Industry sales had been growing slowly for the past four years. In 2013 and 2014, FPC experienced a growth rate that was slightly higher than average, but since that time, they have not kept pace with the leaders. Hence, several firms were found to be increasing their share of the market at the expense of FPC. On the basis of her analysis, Avery concluded that the primary cause of the market share erosion the firm is now experiencing is the change in profile characteristics of the target market, along with FPC's failure to adapt its marketing strategy to reflect new environmental conditions. Up to now, Falconville Pump Company's marketing strategy has focused only on the engineering aspects of the products, and the firm's promotional literature reflects this orientation. Such an emphasis is considered to be appropriate for two reasons. First, engineering excellence has always been the hallmark of FPC. The rating of the company's products as most durable in the industry reflects this attention to technical details. Second, the primary customer contacts are the design engineers who must integrate the FPC equipment into larger systems. In the past, these individuals have always been inclined to focus their attention on technical specifications of the pumping equipment, so promotional literature is designed to answer the most frequently asked questions. This marketing strategy worked well until the late 2000s or early 2010s, partly because expenditures on pumping equipment for new facilities tend to be a very small fraction of the total capital outlay for the larger project and therefore, are not usually subjected to a separate rigorous analysis, and partly because capital was readily available at reasonable rates to finance the purchases. As interest rates started to rise dramatically toward the end of 2009, however, the sales force found it increasingly difficult to convince customers to buy FPC equipment solely on the basis of engineering performance characteristics. Increasingly, economic aspects of the proposed purchase have begun to dominate the sales effort. As customers' expansion plans were scaled back, the pumping equipment was no longer looked upon as only a small piece of a much larger project. Rather, prospective purchasers started to view expenditures on pumping equipment as involving, in their own right, a significant commitment of scarce and expensive capital resources. In more and more situations, the new equipment would replace an existing pumping system that was still serviceable, so FPC salespersons were compelled to demonstrate that the economic benefits from replacing the equipment immediately would more than offset the capital cost. By not recognizing the implications of this fundamental shift in the requirements for effective selling in a different target market and then adapting the marketing strategy and promotional material accordingly better to support the sales force, FPC placed itself at a competitive disadvantage. Other companies were quick to seize and exploit the opportunity, and, particularly in the past two years, they succeeded in taking customers away from Falconville Pump Company. Avery uncovered two additional pieces of information that both she and Joiner believed to be of particular significance. First, the companies that appeared to be gaining market share at FPC's expense stressed to the greatest extent the economics of replacement decisions in their promotional literature and sales presentations. All of them used a discounted cash flow (DCF) approach to convince potential customers of the advantages of replacing old pumping systems with the new high-efficiency models. Second, the most successful of FPC's salespersons in the past four years were engineers who had received formal college training in engineering economics. These individuals, who were trained in the use of DCF methodology, had employed their knowledge to refine their own sales approach and develop supplemental material. By doing so, they were able to generate substantially more sales than their untrained peers. Because of these facts, Avery concluded that as soon as possible, Falconville Pump Company should develop appropriate promotional literature and train all its sales force in the use of discounted cash flow project evaluation techniques. Joiner admitted that this appeared to be a sound recommendation, and he saw no reason why it should not be implemented immediately. As he pondered the information in Avery's report, though, he had the uneasy feeling that the implications of the decision were far more pervasive than they appeared to be on the surface. DCF techniques had never been used at Falconville Pump Company for any purpose, the payback method being the preferred tool for capital expenditure analysis. The more Joiner reflected on Avery's report, though, the more he started to question whether this was a wise policy. FPC's customers included some of the largest and best-run companies in the world. If they required an economic analysis based on discounted cash flow methodology tor their own capital budgeting decisions, then perhaps FPC was making a strategic error and should reevaluate its policies. Joiner had been exposed to the mechanics of DCF calculations at an executive development seminar in the mid-1990s, but he really did not understand why DCF is considered superior to other economic evaluation methodologies or how using payback could lead to less- effective resource allocations. At the executive committee meeting the next afternoon Joiner explained his reservations about continued total reliance on payback and his thoughts about the introduction of discounted cash flow techniques in FPC's internal budgeting and marketing operations. He quickly discovered that no one in the room knew much more than he did about the strengths and weaknesses of the various economic analysis techniques. Richard Phillips, vice-president for finance, was generally supportive of the suggested changes, but he proposed that a feasibility study be conducted as a first step. A second-year M.B.A. student with several years of work experience in the finance area, Sharon Stewart, had recently started an internship in his division, and Phillips believed this to be an excellent project for her to undertake. Avery interrupted to remind Joiner of the pressing need for prompt action in her division to develop promotional literature and train the sales force in the use of DCF techniques. Only after this had been done, she asserted, should the broader implications for FPC's internal operations be considered. Joiner decided that the best course of action was first, to find out how well Stewart is versed in capital budgeting techniques, and second, if the training proves to be adequate, to ask her to work on the marketing division project during her internship. When Joiner questioned Stewart, he was delighted to learn that not only had she worked in the economic evaluation department in her former job, she also had taken an entire course dealing with capital expenditure decisions. (Stewart, for her part, was surprised to learn that FPC was still using the payback method.) She readily agreed to the assignment in the marketing department, and she and Avery decided to start by analyzing one of the standard pumping systems. The following facts, which Avery indicated were fairly typical, were to be used in the illustrative material: 1. The equipment has a delivered cost of $105,000. An additional $3,000 is required to install and test the new system 2. The new pumping system is classified by the IRS as 5-year property, although it has an 8-year estimated service life. For assets classified by the IRS as 5-year property, the Modified Accelerated Cost Recovery System (MACRS) permits the company to depreciate the asset over 6 years at the following rates: Year 1 = 20 percent, Year 2 = 32 percent, Year 3 = 19 percent, Year 4 = 12 percent, Year 5 = 11 percent, Year 6 = 6 percent. At the end of 8 years, the salvage value is expected to be around 5 percent of the original purchase price, so the best estimate of salvage value at the end of the equipment's service life is $5,300, with removal costs of $1,200. 3. The existing pumping system was purchased at $45,000 eight years ago and has been depreciated on a straight-line basis over its economic life of 10 years. If the existing system is removed from the well and crated for pickup, it can be sold for $3,500 before tax. It will cost $1,000 to remove the system and crate it. 4. At the time of replacement, the firm will need to increase its net working capital requirements by $4,500 to support inventories. 5. The new pumping system offers lower maintenance costs and frees personnel who would otherwise have to monitor the system. In addition, it reduces product wastage because of a higher cooling efficiency. In total, it is estimated that the yearly savings will amount to $25,000 if the new pumping system is used. 6. The firm has its target debt ratio of 30 percent, and its cost of new debt is 10 percent. Its expected dividend per share next year, Ds, is $2.00 with a future growth rate of 6 percent per year. The firm's current stock price, Po, is $40.00. The firm uses its overall weighted average cost of capital in evaluating average risk projects, and the replacement project is perceived to be of average risk. 7. The firm's federal-plus-state tax rate is 30 percent, and this rate is projected to remain fairly constant into the future. QUESTIONS (Please show all your work either through Excel formulas/equations on the Cash Flow Estimation Worksheet or in separate tables at the bottom of your spreadsheet, whenever applicable. NO WORK SHOWN, NO POINTS.) (8 pts) 1. Compute the firm's weighted average cost of capital given the info/data in the case. What other approaches/methods can be used to measure the firm's cost of equity and thus its WACC? To that end, what additional info/data would you need? (Hint: A firm's weighted average cost of capital is equal to Ka = Wa(Ka) 1 - t) + WeKe, where Wa and We are the weights of debt and equity in the capital structure; K and K, are the respective costs of debt and equity; and t is the corporate tax rate; Do no round up your WACC figure.) (34 pts) 2. Develop a capital budgeting schedule using the attached Cash Flow Estimation Worksheet (Excel spreadsheet) that should list all relevant cash flow items and amounts related to the replacement project over the 8-year expected life of the new pumping system. (Reference Reading: "Cash Flow Analysis Example (RIC Project)", one of required Readings for the course.) (8 pts) 3. Based on the capital budgeting schedule, evaluate the replacement project by computing NV, IRR, MIRR, and Payback Period. Would you recommend to accept or reject the replacement project based solely on your DCF analysis so far? (10 pts) 4. Before you make the final accept/reject decision, what other factors and approaches would you consider further? Discuss also how to PRACTICALLY take into account those factors and approaches in the capital budgeting decision process, whenever applicable. (Reference Reading: (1) Textbook Chapter 11; and (2) "Capital Asset Management Process: the Case of Hose & Fittings Corporation" by Bae et al., International Journal of Managerial Finance (IJMF), Vol. 1, No. 3, 2005, pp. 204-220, one of required Readings for the course.) (END) FALCONVILLE PUMP COMPANY - CASH FLOW ESTIMATION WORK WORKSHEET Input Data Cost of NEW equipment Annual dep. of old equipment Salvage value new equipment OLD equipment's depreciable life left Coat of old equipment Olid equipment's depreciated years Depreciation of old equipment till dete Annal cost savings Salvage value of old equipment Removal cost of old equipment Tax rate Removal cost of new equipment WACC Networking capital requirement =0 =1 3 t=5 t=6 t=8 INVESTMENT OUTLAY 1 2 3 t=2 3 I 5 6 II OPERATING CASH FLOWS OVER THE PROJECT'S LIFE 7 8 9 10 11 12 III TERMINAL FEAR CASH FLOWS 13 14 15 16 17 IV NET CASH FLOWS 18 V RESULTS NPV IRR MIRR Payback period = DECISION BASED ON YOUR ANALYSIS: ANSWERS TO QUESTIONS: Q#1: Q#2: Q#3: Q#4