Answered step by step

Verified Expert Solution

Question

1 Approved Answer

Answer the following 3 questions after reading the text below. Case# 16 1.What were the appropriate hurdle rates for the two segments? 2.Was the products

Answer the following 3 questions after reading the text below.

Case# 16

1.What were the appropriate hurdle rates for the two segments?

2.Was the products and systems segment underperforming, as suggested by Yossarian?

3.How should Teletech respond to the raider?

Margaret Weston, Teletech Corporations CFO, learned of Victor Yossarians letter late one evening in early October 2005. Quickly, she organized a team of lawyers and finance staff to assess the threat. Maxwell Harper, the firms CEO, scheduled a teleconference meeting of the firms board of directors for the following afternoon. Harper and Weston agreed that before the meeting they needed to fashion a response to Yossarians assertions about the firms returns.

Ironically, returns had been the subject of debate within the firms circle of senior managers in recent months. A number of issues had been raised about the hurdle rate used by the companywhen evaluating performance and setting the firms annual capital budget. As the company was expected to invest nearly $2 billion in capital projects in the coming year, gaining closure and consensus on those issues had become an important priority for Weston. Now, Yossarians letter lent urgency to the discussion.

In the short run, Weston needed to respond to Yossarian. In the long run, she needed to assess the competing viewpoints on Teletechs returns, and she had to

recommend new policies as necessary. What should the hurdle rates be for Teletechs two business segments, telecommunications services and its newer products and systems unit? Was the products and systems segment really paying its way?

The Company

The Teletech Corporation, headquartered in Dallas, Texas, defined itself as a provider of integrated information movement and management. The firm had two main busi- ness segments: telecommunications services, which provided long-distance, local, and cellular telephone service to business and residential customers, and the products and systems segment, which engaged in the manufacture of computing and telecommunications equipment.

In 2004, telecommunications services had earned a return on capital (ROC)1 of 9.10%; products and systems had earned 11%. The firms current book value of net assets was $16 billion, consisting of $11.4 billion allocated to telecommunications serv- ices, and $4.6 billion allocated to products and systems. An internal analysis suggested that telecommunications services accounted for 75% of the market value (MV) of Teletech, while products and systems accounted for 25%. Overall, it appeared that the firms prospective ROC would be 9.58%. Top management applied a hurdle rate of 9.30% to all capital projects and in the evaluation of the performance of business units.

Over the past 12 months, Teletechs shares had not kept pace with the overall stock market or with industry indexes for telephone, equipment, or computer stocks. Securities analysts had remarked on the firms lackluster earnings growth, pointing especially to increasing competition in telecommunications, as well as disappointing performance in the Products and Systems segment. A prominent commentator on TV opined, Theres no precedent for a hostile takeover in this sector, but, in the case of Teletech, there is every reason to try.

Telecommunications Services

The telecommunications services segment provided long-distance, local, and cellular telephone service to more than 7 million customer lines throughout the Southwest and Midwest. Revenues in this segment grew at an average rate of 3% during 200004. In 2004, segment revenues, net operating profit after tax (NOPAT), and net assets were $11 billion, $1.18 billion, and $11.4 billion, respectively.

Since the court-ordered breakup of the Bell System telephone monopoly in 1983, Teletech had coped with the gradual deregulation of its industry through aggressive expansion into new services and geographical regions. Most recently, the firm had been a leading bidder for cellular telephone operations and for licenses to offer personal communications services (PCS). In addition, the firm had purchased a number of telephone-operating companies through privatization auctions in Latin America. Finally, the firm had invested aggressively in new technologyprimarily, digital switches and optical-fiber cablesin an effort to enhance its service quality. All of those strategic moves had been costly: the capital budget in this segment had varied between $1.5 billion and $2 billion in each of the previous 10 years.

Unfortunately, profit margins in the telecommunications segment had been under pressure for several years. Government regulators had been slow to provide rate relief to Teletech for its capital investments. Other leading telecommunications providers had expanded into Teletechs geographical markets and invested in new technology and quality-enhancing assets. Teletechs management noted that large cable-TV companies had aggressively entered the telecommunications market and continued the pressure on profit margins.

Nevertheless, Teletech was the dominant service provider in its geographical markets and product segments. Customer surveys revealed that the company was the leader in product quality and customer satisfaction. Its management was confident that the company could command premium prices no matter how the industry might evolve.

Products and Systems

Before 2000, telecommunications had been the companys core business, supplemented by an equipment-manufacturing division that produced telecommunications components. In 2000, the company acquired a leading computer-workstation manufacturer with the goal of applying state-of-the-art computing technology to the design of telecommunications equipment. The explosive growth in the microcomputer market and the increased usage of telephone lines to connect home- and office-based computers with mainframes convinced Teletechs management of the potential value of marrying telecommunications equipment with computing technology. Using Teletechs capital base, borrowing ability, and distribution network to catapult growth, the products and systems segment increased its sales by nearly 40% in 2004. This segments 2004 NOPAT and net assets were $480 million and $4.6 billion, respectively.

The products and systems segment was acknowledged as a technology leader in the industry. While this accounted for its rapid growth and pricing power, maintenance of that leadership position required sizable investments in research and development (R&D) and fixed assets. The rate of technological change was increasing, as witnessed by sudden major write-offs by Teletech on products that, until recently, management had thought were still competitive. Major computer manufacturers were entering the telecommunications-equipment industry. Foreign manufacturers were proving to be stiff competition for bidding on major supply contracts.

Focus on Value at Teletech

We will create value by pursuing business activities that earn premium rates of return.

Teletech Corporation mission statement (excerpt)

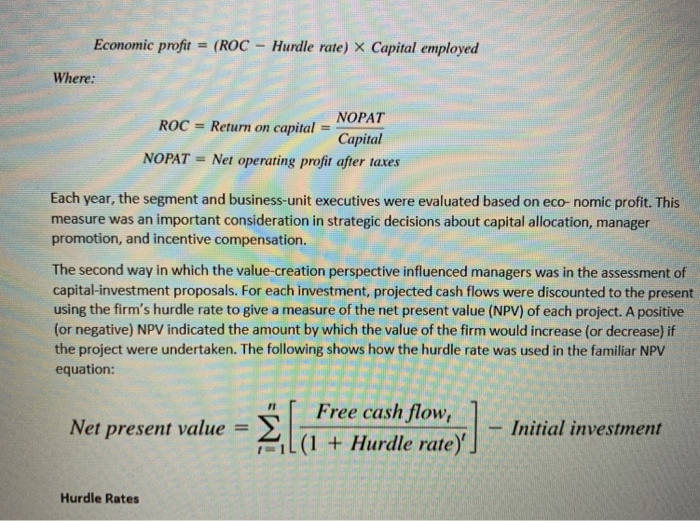

Translating Teletechs mission statement into practice had been a challenge for Margaret Weston. First, it had been necessary to help managers of the segments and business units understand what creating value meant. Because the segments and smaller business units did not issue securities in the capital markets, the only objective measure of value was the securities prices of the whole corporationbut the activities of any particular manager might not be significant enough to drive Teletechs securities prices. Therefore, the company had adopted a measure of value creation for use at the segment and business-unit level that would provide a proxy for the way investors would view each units performance. This measure, called economic profit, multiplied the excess rate of return of the business unit by the capital it used:

Each year, the segment and business-unit executives were evaluated based on eco- nomic profit. This measure was an important consideration in strategic decisions about capital allocation, manager promotion, and incentive compensation.

The second way in which the value-creation perspective influenced managers was in the assessment of capital-investment proposals. For each investment, projected cash flows were discounted to the present using the firms hurdle rate to give a measure of the net present value (NPV) of each project. A positive (or negative) NPV indicated the amount by which the value of the firm would increase (or decrease) if the project were undertaken. The following shows how the hurdle rate was used in the familiar NPV equation:

Hurdle Rates

The hurdle rate used in the assessments of economic profit and NPV had been the focus of considerable debate in recent months. This rate was based on an estimate of Teletechs weighted average cost of capital (WACC). Management was completely satisfied with the intellectual relevance of a hurdle rate as an expression of the opportunity cost of money. The notion that the WACC represented this opportunity cost had been hotly debated within the company, and while its measurement had never been considered wholly scientific, it was generally accepted.

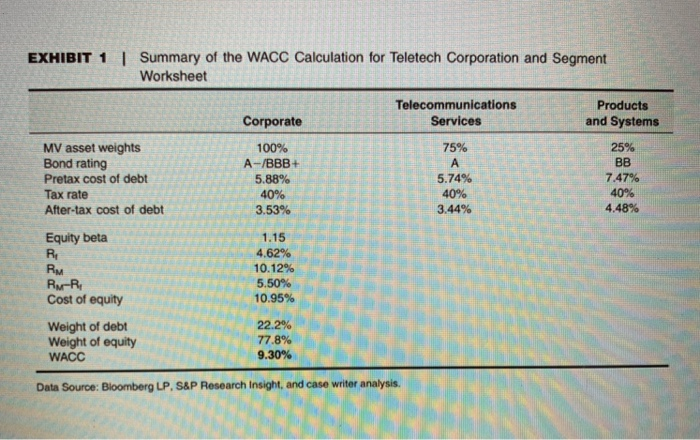

Teletech was split-rated between A and BBB. An investment banker recently suggested that, at those ratings, new debt funds might cost Teletech 5.88% (about 3.53% after a 40% tax rate). With a beta of 1.15, the cost of equity might be about 10.95%. At market-value weights of 22% for debt and 78% for equity, the resulting WACC would be 9.30%. Exhibit 1 summarizes the calculation. The hurdle rate of 9.30% was applied to all investment and performance-measurement analyses at the firm.

Arguments for Risk-Adjusted Hurdle Rates

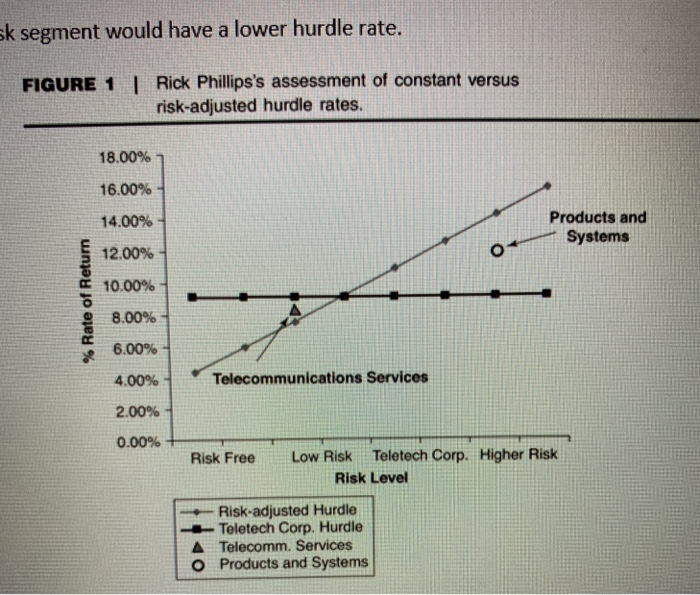

How the rate should be used within the company in evaluating projects was another point of debate. Given the differing natures of the two businesses and the risks each one faced, differences of opinion arose at the segment level over the appropriateness of measuring all projects against the corporate hurdle rate of 9.30%. The chief advocate for multiple rates was Rick Phillips, executive vice president of telecommunications services, who presented his views as follows:

Each phase of our business is different. They must compete differently and must draw on capital differently. Given the historically stable nature of this industry, many telecommunications companies can raise large quantities of capital from the debt markets. In operations comparable to telecommunications services, 50% of the necessary capital is raised in the debt markets at interest rates reflecting solid A quality, on average. This is better than Teletechs corporate bond rating of A/BBB.

I also have to believe that the cost of equity for telecommunications services is lower than it is for products and systems. Although the products and systems segments sales growth and profitability have been strong, its risks are high. Independent equipment manufacturers are financed with higher-yielding BB-rated debt and a greater proportion of equity.

In my book, the hurdle rate for products and systems should reflect those higher costs of funds. Without the risk-adjusted system of hurdle rates, telecommunications services will gradually starve for capital, while products and systems will be force-fedthats be- cause our returns are less than the corporate hurdle rate, and theirs are greater. Telecommunications services lowers the risk of the whole corporation, and should not be penalized. Heres a rough graph of what I think is going on (Figure 1):

Telecommunications services, which can earn 9.10% on capital, is actually profitable on a risk-adjusted basis, even though it is not profitable compared to the corporate hurdle rate. The triangle shape on the drawing shows about where telecommunications services is located. My hunch is that the reverse is true for products and systems [P&S], which promises to earn 11.0% on capital. P&S is located on the graph near the little circle. In deciding how much to loan us, lenders will consider the composition of risks. If money flows into safer investments, over time the cost of their loans to us will decrease.

Our stockholders are equally as concerned with risk. If they perceive our business as being more risky than other companies are, they will not pay as high a price for our earnings. Perhaps this is why our price-to-earnings ratio is below the industry average most of the time. It is not a question of whether we adjust for riskwe already do, informally. The only question in my mind is whether we make those adjustments systematically or not.

While multiple hurdle rates may not reflect capital-structure changes on a day-to-day basis, over time they will reflect prospects more realistically. At the moment, as I under- stand it, our real problem is an inadequate and very costly supply of equity funds. If we are really rationing equity capital, then we should be striving for the best returns on equity for the risk. Multiple hurdle rates achieve that objective.

Implicit in Phillipss argument, as Weston understood it, was the notion that if each segment in the company had a different hurdle rate, the costs of the various forms of capital would remain the same. The mix of capital used, however, would change in the calculation. Low-risk operations would use leverage more extensively, while the high-risk divisions would have little to no debt funds. This lower risk segment would have a lower hurdle rate.

Opposition to Risk-Adjusted Hurdle Rates

While several others within Teletech supported Phillipss views, opposition was strong within the products and systems segment. Helen Buono, executive vice president of products and systems, expressed her opinion as follows:

All money is green. Investors cant know as much about our operations as we do. To them the firm is a black box; they hire us to take care of what is inside the box, and judge us by the dividends coming out of the box. We cant say that one part of the box has a different hurdle rate than another part of the box if our investors dont think that way. Like I say, all money is green: all investments at Teletech should be judged against one hurdle rate.

Multiple hurdle rates are illogical. Suppose that the hurdle rate for telecommunications services was much lower than the corporate-wide hurdle rate. If we undertook investments that met the segment hurdle rate, we would be destroying shareholder value because we werent meeting the corporate hurdle rate.

Our job as managers should be to put our money where the returns are best. A single hurdle rate may deprive an under profitable division of investments in order to channel more funds into a more profitable division, but isnt that the aim of the process? Our challenge today is simple: we must earn the highest absolute rates of return that we can get.

In reality, we dont finance each division separately. The corporation raises capital based on its overall prospects and record. The diversification of the company probably helps keep our capital costs down and enables us to borrow more in total than the sum of the capabilities of the divisions separately. As a result, developing separate hurdle rates is both unrealistic and misleading. All our stockholders want is for us to invest our funds wisely in order to increase the value of their stock. This happens when we pick the most promising projects, irrespective of the source.

Margaret Westons Concerns

As Weston listened to these arguments, presented over the course of several months, she became increasingly concerned about several related considerations. First, Teletechs corporate strategy had directed the company toward integrating the two segments. One effect of using multiple hurdle rates would be to make justifying high-technology research and application proposals more difficult, as the required rate of return would be increased. On the one hand, she thought, perhaps multiple hurdle rates were the right idea, but the notion that they should be based on capital costs rather than strategic considerations might be wrong. On the other hand, perhaps multiple rates based on capital costs should be used, but, in allocating funds, some qualitative adjustment should be made for unquantifiable strategic considerations. In Westons mind, the theory was certainly not clear on how to achieve strategic objectives when allocating capital.

Second, using a single measure of the cost of money (the hurdle rate or discount factor) made the NPV results consistent, at least in economic terms. If Teletech adopted multiple rates for discounting cash flows, Weston was afraid that the NPV and economic-profit calculations would lose their meaning and comparability across business segments. To her, a performance criterion had to be consistent and understandable, or it would not be useful.

In addition, Weston was concerned about the problem of attributing capital structures to divisions. In the telecommunications services segment, a major new switching station might be financed by mortgage bonds. In products and systems, however, it was impossible for the division to borrow directly; indeed, any financing was only feasible because the corporation guaranteed the debt. Such projects were considered highly riskyat best, perhaps, warranting only a minimal debt structure. Also, Weston considered the debt-capacity decision difficult enough for the corporation as a whole, let alone for each division. Judgments could only be very crude.

In further discussions with others in the organization about the use of multiple hurdle rates, Weston discovered two predominant themes. One argument held that investment decisions should never be mixed with financing decisions. A firm should first decide what its investments should be and then determine how to finance them most efficiently. Adding leverage to a present-value calculation would distort the results. The use of multiple hurdle rates was simply a way of mixing financing with investment analysis. This argument also held that a single rate made the risk decision clear-cut. Management could simply adjust its standard (NPV or economic profit) as the risks increased.

The contrasting line of reasoning noted that the WACC tended to represent an aver- age market reaction to a mixture of risks. Lower-than-average-risk projects should probably be accepted even when they did not meet the weighted-average criterion. Higher-than-normal-risk projects should provide a return premium. While the multiple- hurdle-rate system was a crude way to achieve this end, at least it was a step in the right direction. Moreover, some argued that Teletechs objective should be to maximize return on equity funds, and because equity funds were and would remain a comparatively scarce resource, a multiple-rate system would tend to maximize returns to stock- holders better than a single-rate system would.

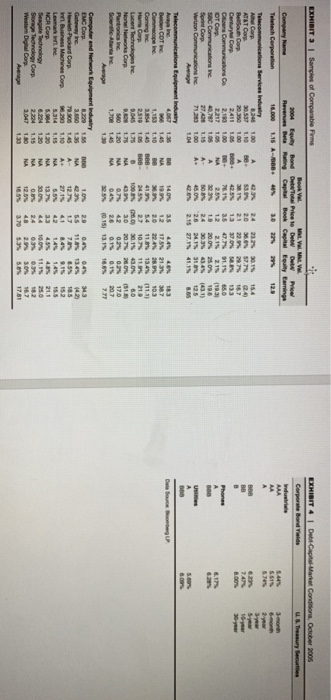

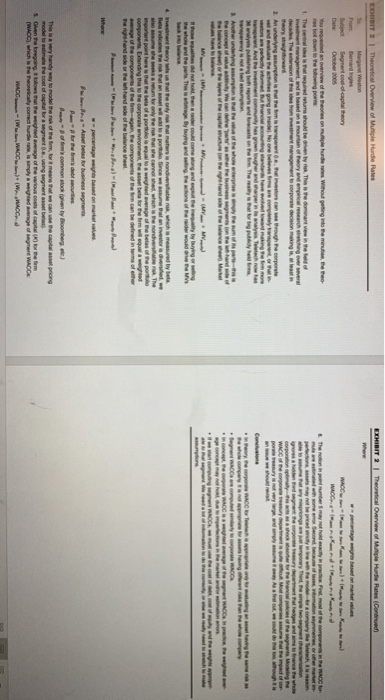

To help resolve these issues, Weston asked her assistant, Bernard Ingles, to summarize the scholarly thought regarding multiple hurdle rates. His memorandum is given in Exhibit 2. She also requested that Ingles obtain samples of firms comparable with the telecommunications services segment and the products and systems unit that might be used in deriving segment WACCs. A summary of the data is given in Exhibit 3. Information on capital-market conditions in October 2005 is given in Exhibit 4.

Conclusion

Weston could not realistically hope that all the issues before her would be resolved in time to influence Victor Yossarians attack on management. But the attack did dictate the need for an objective assessment of the performance of Teletechs two segmentsthe choice of hurdle rates would be very important in the analysis. She did want to institute a pragmatic system of appropriate hurdle rates (or one rate), how- ever, that would facilitate judgments in the changing circumstances faced by Teletech. What were the appropriate hurdle rates for the two segments? Was the products and systems segment underperforming, as suggested by Yossarian? How should Teletech respond to the raider?

Step by Step Solution

There are 3 Steps involved in it

Step: 1

Get Instant Access to Expert-Tailored Solutions

See step-by-step solutions with expert insights and AI powered tools for academic success

Step: 2

Step: 3

Ace Your Homework with AI

Get the answers you need in no time with our AI-driven, step-by-step assistance

Get Started