Answered step by step

Verified Expert Solution

Question

1 Approved Answer

Answer the following questions based on the reading The impact of Medicare on Access to And Affordability of Health Care. All the questions can

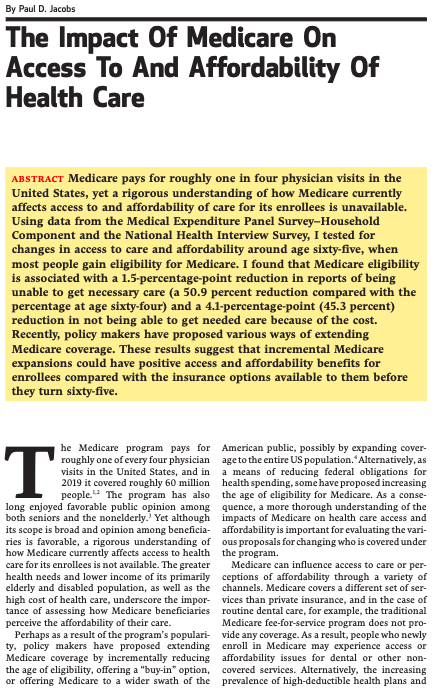

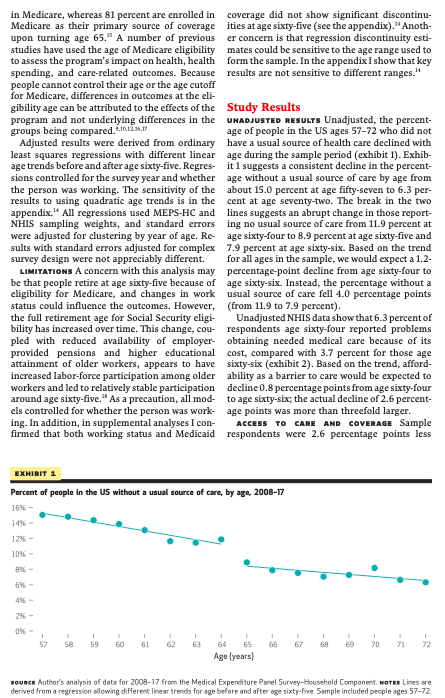

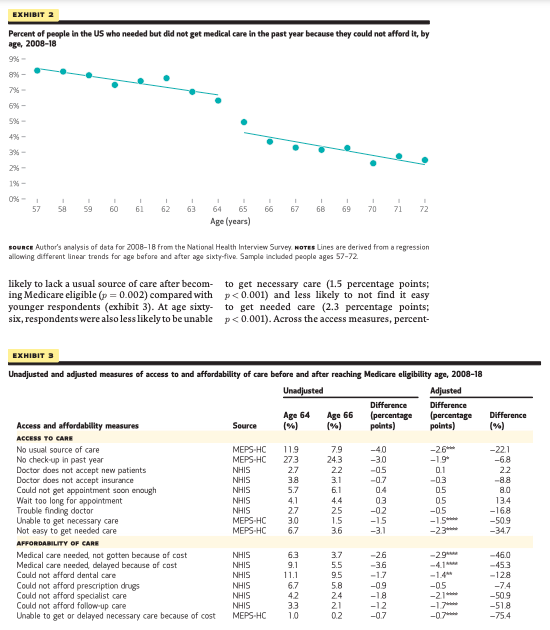

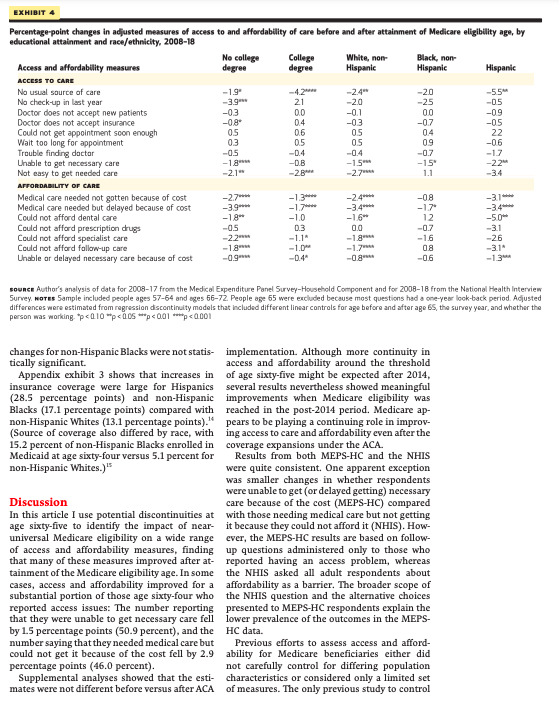

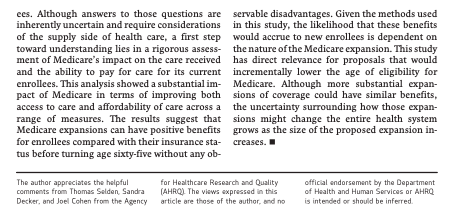

Answer the following questions based on the reading "The impact of Medicare on Access to And Affordability of Health Care". All the questions can be answered with the information available in the reading in combination with lecture material. 1- According to this reading, is this statement true or false? [0.5 point] When a person is insured (i.e., has health insurance), this means this person has no accessibility issues regarding healthcare anymore. Explain. 2- From a policy perspective, why does the author think that is it important to look at the impact of Medicare on accessibility to healthcare and affordable coverage? [1 point] 3- Are comparisons between Medicare recipient's accessibility and accessibility of the privately insured an accurate approach to use to address the research question of this paper? [Hint: Think of counterfactuals and what is being compared] [1 point] 4- How does the author propose to solve the issue raised in Question 3? Do you think the proposed solution is a good approach regarding how to look at the causal impact of Medicare? Explain. [1 point] 5- In the solution proposed in Q4 what is the author exactly testing? (You can think of the causal effect to answer the question)? [0.5 point] By Paul D. Jacobs The Impact Of Medicare On Access To And Affordability Of Health Care ABSTRACT Medicare pays for roughly one in four physician visits in the United States, yet a rigorous understanding of how Medicare currently affects access to and affordability of care for its enrollees is unavailable. Using data from the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey-Household Component and the National Health Interview Survey, I tested for changes in access to care and affordability around age sixty-five, when most people gain eligibility for Medicare. I found that Medicare eligibility is associated with a 1.5-percentage-point reduction in reports of being unable to get necessary care (a 50.9 percent reduction compared with the percentage at age sixty-four) and a 4.1-percentage-point (45.3 percent) reduction in not being able to get needed care because of the cost. Recently, policy makers have proposed various ways of extending Medicare coverage. These results suggest that incremental Medicare expansions could have positive access and affordability benefits for enrollees compared with the insurance options available to them before they turn sixty-five. T he Medicare program pays for roughly one of every four physician visits in the United States, and in 2019 it covered roughly 60 million people. The program has also long enjoyed favorable public opinion among both seniors and the nonelderly. Yet although its scope is broad and opinion among beneficia ries is favorable, a rigorous understanding of how Medicare currently affects access to health care for its enrollees is not available. The greater health needs and lower income of its primarily elderly and disabled population, as well as the high cost of health care, underscore the impor- tance of assessing how Medicare beneficiaries perceive the affordability of their care. Perhaps as a result of the program's populari- ty, policy makers have proposed extending Medicare coverage by incrementally reducing the age of eligibility, offering a "buy-in" option, or offering Medicare to a wider swath of the American public, possibly by expanding cover- age to the entire US population. Alternatively, as a means of reducing federal obligations for health spending, some have proposed increasing the age of eligibility for Medicare. As a conse- quence, a more thorough understanding of the impacts of Medicare on health care access and affordability is important for evaluating the vari- ous proposals for changing who is covered under the program. Medicare can influence access to care or per- ceptions of affordability through a variety of channels. Medicare covers a different set of ser- vices than private insurance, and in the case of routine dental care, for example, the traditional Medicare fee-for-service program does not pro- vide any coverage. As a result, people who newly enroll in Medicare may experience access or affordability issues for dental or other non- covered services. Alternatively, the increasing prevalence of high-deductible health plans and other increases in cost sharing among private plans could increase the perceived affordability of Medicare. For people with limited or no health coverage before age sixty-five, access to care and perceived affordability may well improve on en- rolling in Medicare. Understanding access and affordability issues is critical for Medicare's high-need and low- income population, yet a gap exists in what we know about Medicare's current role in providing accessible care and affordable coverage. Re- search broadly shows that access to care not only is an outcome of whether someone has coverage but also depends on their type of health insur- ance. And although research consistently sug- gests that Medicare provides roughly compara- ble access compared with private insurance, previous efforts have generally relied on simple comparisons between people with different types of insurance. For instance, Medicare ben- eficiaries report that their access to care is com- parable to or better than that of people with private insurance," beneficiaries are able to find a new doctor without a problem,' and physicians accept new beneficiaries at roughly the same rate as they do patients with private insurance." How- ever, a fundamental shortcoming with this line of inquiry is that the populations being com- pared are inherently different. More rigorous analyses of Medicare have been conducted assessing discontinuities using the age of eligibility. These studies have documented changes in mortality at age sixty-five as well as changes in the receipt of care, including mam- mography and rehabilitation. Only one study to date has rigorously assessed changes in ac- cess-to-care measures for Medicare enrollees.2 However, these authors studied only two access measures (whether people delayed care or did not get care because of cost in the past year) and used data that are now nearly two decades old. In this study I used more recent data and a regression discontinuity design to test for changes in multiple measures of access and affordability just before and just after the attain- ment of age sixty-five, when most people gain Medicare eligibility. This design exploited the fact that only a small share of the near-elderly US population is enrolled in Medicare and a large majority of people obtain Medicare as their primary source of coverage at age sixty-five. Study Data And Methods POPULATION I examined measures of access to and affordability of care using data from both the 2008-17 Medical Expenditure Panel Survey- Household Component (MEPS-HC) and the 2008-18 National Health Interview Survey (NHIS). The primary sample was limited to respondents ages 57-72, excluding people age 65 at the time of the interview because survey questions on access to care and affordability typ- ically cover the previous twelve months. ACCESS OUTCOMES Using MEPS-HC data, I as- sessed the percentage-point change at age sixty- five in whether people had a usual source of care, had a routine checkup in the past year, delayed getting necessary medical care in the past year, and were unable to get necessary care in the past year. Using data from the NHIS Sample Adult file, I examined changes in the following re- ported experiences (all in the past twelve months): people were told by a doctor's office that they would not accept the person as a new patient, they were told by a doctor's office that they did not accept the person's health coverage, they could not get an appointment soon enough, they waited too long in the doctor's office, and they had trouble finding a doctor who would see them. AFFORDABILITY OUTCOMES To assess percep- tions of affordability, I examined whether people were unable to get or delayed getting necessary medical care because of the cost in the past twelve months (MEPS-HC) and questions asking whether people did not get care in the past twelve months because they could not afford it for five types of care (NHIS Sample Adult file): general medical care, prescription medicines, dental care, specialist care, and follow-up." COVERAGE In supplemental analyses I used MEPS-HC data to assess changes at age sixty-five in whether people had any health insurance cov- erage at the time of the survey (see the online appendix)." ANALYSIS Results were expressed as percent- age-point differences in those reporting issues accessing or affording care before and after the age of Medicare eligibility. In addition, to show the relative importance of these changes, results were calculated as the percentage change in the outcomes compared with means for the sixty- four-year-old population in my sample. I also calculated results by educational attainment and race/ethnicity. Results were also calculated for survey years before and after the implemen- tation of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) to test whether increases in insurance coverage for the nonelderly population minimized potential changes arising from newly obtaining coverage at the threshold of age sixty-five. Using a regression discontinuity design, I test- ed for discontinuous changes in measures of ac- cess to care and affordability of coverage before and after reaching age sixty-five. This design ex- ploited the fact that only 6-11 percent of the near- elderly US population (ages 57-64) are enrolled in Medicare, whereas 81 percent are enrolled in Medicare as their primary source of coverage upon turning age 65." A number of previous studies have used the age of Medicare eligibility to assess the program's impact on health, health spending, and care-related outcomes. Because people cannot control their age or the age cutoff for Medicare, differences in outcomes at the eli- gibility age can be attributed to the effects of the program and not underlying differences in the groups being compared. 10.12.17 Adjusted results were derived from ordinary least squares regressions with different linear age trends before and after age sixty-five. Regres- sions controlled for the survey year and whether the person was working. The sensitivity of the results to using quadratic age trends is in the appendix." All regressions used MEPS-HC and NHIS sampling weights, and standard errors were adjusted for clustering by year of age. Re- sults with standard errors adjusted for complex survey design were not appreciably different. LIMITATIONS A concern with this analysis may be that people retire at age sixty-five because of eligibility for Medicare, and changes in work status could influence the outcomes. However, the full retirement age for Social Security eligi- bility has increased over time. This change, cou- pled with reduced availability of employer- provided pensions and higher educational attainment of older workers, appears to have increased labor-force participation among older workers and led to relatively stable participation around age sixty-five." As a precaution, all mod- els controlled for whether the person was work- ing. In addition, in supplemental analyses I con- firmed that both working status and Medicaid EXHIBIT 1 coverage did not show significant discontinu- ities at age sixty-five (see the appendix)." Anoth- er concern is that regression discontinuity esti- mates could be sensitive to the age range used to form the sample. In the appendix I show that key results are not sensitive to different ranges." I 57 58 59 60 61 Study Results UNADJUSTED RESULTS Unadjusted, the percent- age of people in the US ages 57-72 who did not have a usual source of health care declined with age during the sample period (exhibit 1). Exhib- it 1 suggests a consistent decline in the percent- age without a usual source of care by age from about 15.0 percent at age fifty-seven to 6.3 per- cent at age seventy-two. The break in the two lines suggests an abrupt change in those report- ing no usual source of care from 11.9 percent at age sixty-four to 8.9 percent at age sixty-five and 7.9 percent at age sixty-six. Based on the trend for all ages in the sample, we would expect a 1.2- percentage-point decline from age sixty-four to age sixty-six. Instead, the percentage without a usual source of care fell 4.0 percentage points (from 11.9 to 7.9 percent). Unadjusted NHIS data show that 6.3 percent of respondents age sixty-four reported problems obtaining needed medical care because of its cost, compared with 3.7 percent for those age sixty-six (exhibit 2). Based on the trend, afford- ability as a barrier to care would be expected to decline 0.8 percentage points from age sixty-four to age sixty-six; the actual decline of 2.6 percent- age points was more than threefold larger. ACCESS TO CARE AND COVERAGE Sample respondents were 2.6 percentage points less Percent of people in the US without a usual source of care, by age, 2008-17 16% - 14% - 12% - 10% - 8% - 6% - 4% - 2% - 0%- 65 Age (years) 66 67 69 70 71 72 Sounce Author's analysis of data for 2008-17 from the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey-Household Component. NOTES Lines are derived from a regression allowing different linear trends for age before and after age sixty-five. Sample included people ages 57-72. EXHIBIT 2 Percent of people in the US who needed but did not get medical care in the past year because they could not afford it, by age, 2008-18 9%- 8% - 7% - 6%- 5%- 4%- 3%- 2%- 1%- 0%- 1 57 58 59 EXHIBIT 3 60 61 Sounce Author's analysis of data for 2008-18 from the National Health Interview Survey NOTES Lines are derived from a regression allowing different linear trends for age before and after age sixty-five. Sample included people ages 57-72. likely to lack a usual source of care after becom- ing Medicare eligible (p=0.002) compared with younger respondents (exhibit 3). At age sixty- six, respondents were also less likely to be unable I 62 63 Access and affordability measures ACCESS TO CARE No usual source of care No check-up in past year 6 65 Age (years) Doctor does not accept new patients Doctor does not accept insurance Unadjusted and adjusted measures of access to and affordability of care before and after reaching Medicare eligibility age, 2008-18 Unadjusted Adjusted Difference (percentage Difference points) (96) Could not get appointment soon enough Wait too long for appointment Trouble finding doctor Unable to get necessary care Not easy to get needed care AFFORDABILITY OF CARE Medical care needed, not gotten because of cost Medical care needed, delayed because of cast Could not afford dental care Could not afford prescription drugs Could not afford specialist care Could not afford follow-up care Unable to get or delayed necessary care because of cost I I I 66 67 68 69 70 71 72 to get necessary care (1.5 percentage points; p

Step by Step Solution

★★★★★

3.33 Rating (147 Votes )

There are 3 Steps involved in it

Step: 1

1 The statement When a person is insured ie has health insurance this means this person has no accessibility issues regarding healthcare anymore is fa...

Get Instant Access to Expert-Tailored Solutions

See step-by-step solutions with expert insights and AI powered tools for academic success

Step: 2

Step: 3

Ace Your Homework with AI

Get the answers you need in no time with our AI-driven, step-by-step assistance

Get Started