Question

As Sarah Jenkins, materials manager at Caledon Concrete Mixers, ended her conference call with Jon Del Rosario from corporate purchasing, she wondered what recommendations she

As Sarah Jenkins, materials manager at Caledon Concrete Mixers, ended her conference call with Jon Del Rosario from corporate purchasing, she wondered what recommendations she should make regarding the selection of a gearbox supplier. The corporate purchasing group in Chicago was advocating switching to a new supplier, but Sarah remained concerned about the risks of ending a long-term supply arrangement with a key supplier. It was now December 3, and she wanted to make a final recommendation before the plant shut down for the annual Christmas holiday break.

CALEDON CONCRETE MIXERS

Located north of Toronto, Canada, in Caledon, Ontario, Caledon Concrete Mixers (CCM) was a manufacturer of truck-mounted concrete mixers. Founded in 1910, the company employed 140 people in its 150,000-square-foot plant, including 100 unionized hourly workers, and had annual sales of approximately $25 million. Nearly 40 percent of company sales were exported, mainly to the United States.

CCM had a strong reputation for quality and service in the industry. It operated as a private business until 2003 when it was purchased by Illinois Machinery Corporation (IMC). IMC was a global manufacturer and marketer of access equipment, specialty vehicles, and truck bodies for the defense, concrete placement, refuse to haul, and fire and emergency markets. Annual revenues in the most current fiscal year were $9 billion and IMC had approximately 18,000 employees.

Concrete mixer transport trucks were designed to mix concrete and haul it to the construction site. Customers typically specified the truck model, which was ordered from the original equipment manufacturer. CCM fitted the vehicle with the concrete mixing equipment, which included a large drum and discharge system. Systems were customized based on vehicle size (e.g., two to six axles), discharge system (front or rear), and capacity (maximum capacity to carry 14 cubic yards of payload).

IMC had an operation in St. Louis that manufactured a similar product line to CCM under a different brand name, with annual revenues approximately double the Canadian plant. Although IMC operated under a decentralized model, CCM and the St. Louis operation cooperated in areas of engineering, purchasing, and sales, while operating autonomously with separate leadership teams. One key area for synergies was in supply, where combining purchases between the two operations for some products had yielded significant savings. Jon Del Rosario, purchasing manager in the corporate purchasing group in Chicago, was responsible for coordinating purchasing between the Caledon and St. Louis plants.

Sarah Jenkins was responsible for materials management at CCM. An MBA graduate from the Ivey Business School, Sarah had worked at CCM for more than 20 years. Reporting to the general manager, her responsibilities included logistics and transportation, purchasing, inventory control, and production planning. Her counterparts in finance and accounting, quality, operations, sales, HR, and engineering rounded out the senior management team.

THE GEARBOX

While the concrete mixer truck was in operation, it was necessary to continuously rotate the load to prepare the concrete and avoid consolidation. The gearbox was located at the bottom of the large mixing drum and was used to transmit torque from the hydraulic motor drive shaft, which rotated the drum. The gearbox also permitted the operator to adjust the speed and direction of the rotation.

The gearbox was one of approximately 150 components that CCM used for the assembly of their concrete mixers. The gearbox used by CCM came in two variations, depending on the model of the concrete mixer. Each gearbox cost approximately $3,600 and volumes at CCM ranged from 950 to 1,100 units per year.

CURRENT SUPPLY ARRANGEMENT

CCM and the St. Louis operation both used BGK GmbH as the single source for gearboxes. BGK was a large diversified German manufacturing company with annual revenues of 12 billion euros. The division that supplied CCM produced gearboxes for industrial applications in a wide range of industries, such as material handling equipment, energy, and mining. The company had a reputation for high quality and reliability, although its products were typically more expensive than those of their competitors.

The relationship with CCM and BGK dated back more than 30 years. BGK offered a standard one-year warranty on its gearboxes, but Sarah was not aware that CCM had ever experienced any notable quality problems, problems and customers were generally satisfied with the performance of the product.

IMC had also used BGK as their single supplier for many years. At the time of the acquisition of CCM, the IMC purchasing group was surprised to learn that CCM had a better price for its gearboxes. Prices for both CCM and IMC were aligned following the completion of the acquisition in 2003.

Despite the long history with BGK, both CCM and IMC had become increasingly unhappy with the service and responsiveness of the supplier and its apparent unwillingness to react to their concerns. Strong economic expansion in Asia created an increased demand for BGK gearboxes and the company was unable to expand capacity to keep pace with increasing sales. It had been hampered by a combination of restrictive labor rules in Germany regarding overtime and a steel shortage two years prior.

Second, BGK did not have distribution operations in North America. Gearboxes were shipped via ocean freight and lead times to the Caledon plant ranged from three to five months. As a result, CCM was forced to keep a three-month supply of safety stock inventory on hand. Even with this precaution, supply shortages had threatened plant shutdowns on several occasions during the previous two years. With 50 percent of CCM’s sales coming from four customers, changes in customer orders could have a significant effect on demand and inventories. To add to Sarah’s frustration, BGK shipped only full container loads of 50 units, whereas production in some months was as low as 20 units.

Lastly, customer expectations for warranty and service were increasing, yet BGK was unwilling to extend its warranty coverage without an increase in price. The supplier referenced its quality data, which boasted the lowest failure rate in the industry at 0.5 percent. However, as margins on CCM’s products shrank and customer demands grew, Sarah and her peers in the purchasing organization at IMC had become frustrated by the lack of responsiveness from their supplier and decided to test the marketplace.

SUPPLY OPTIONS

The decision was made in September to solicit RFQs for the combined gearbox volumes of CCM and IMC. Sarah led the RFQ process and identified five potential suppliers, including BGK, two of which were not invited to participate because they currently supplied products exclusively to Asia. The two new firms asked to participate were Moretti SpA and IGR Industries.

The RFQ specified a five-year contract for 100 percent of volumes for CCM and IMC, representing an annual volume of 2,800 to 3,300 units per year. Each supplier was asked to submit quotes in U.S. funds that included stable pricing for the term of the contract, warranty terms, and distribution capabilities, including lead times and North American warehousing arrangements. Delivery would be FOB the London and St. Louis facilities.

IGR Industries was an Italian company, but its manufacturing operations were mainly in Eastern Europe and Asia. Revenues for IGR were approximately 1.5 billion euros, with sales concentrated primarily in Europe and Asia. It had a good reputation for quality, claiming that its failure rate was 1.0 percent. IGR did not currently supply product to North America but proposed setting up a distribution facility in the Missouri region as part of their proposal. Under this arrangement, IGR promised just-in-time delivery to IMC and two-day delivery to CCM. IGR quoted a price of $3,400, with an annual adjustment for currency fluctuations, between the U.S. dollar and the euro, and steel pricing. It also offered a five-year warranty and 30-day payment terms.

Moretti SpA was also an Italian manufacturer with sales of approximately 1 billion euros. It had operations in 18 countries, including the United States. Approximately five years ago, Moretti had experienced a quality problem with its gearbox, involving an oil leak. The oil leak problem became a major issue, as contractors had become increasingly sensitive to potential environmental problems at construction sites. However, according to company officials, the oil leak problem had since been addressed and the company claimed that independent testing indicated a defect rate of 1.5 percent of its product after three years of operation. Moretti quoted a price of $3,200, with an annual adjustment for currency fluctuations between the U.S. dollar and the euro. The company also offered a five-year warranty and a consignment inventory arrangement. Under the consignment inventory system, Moretti would own the inventory at CCM and IMC until the gearboxes were assembled into the vehicle, at which point an invoice would be issued, with a 30-day payment term.

BGK’s proposal was to extend the current supply arrangement, which included a price of $3,600 that was subject to annual adjustments and a standard one-year warranty. Lennart Wagner, the sales representative for BGK, indicated that the company was not prepared to set up a North American distribution facility. He indicated to Sarah that BGK was the world leader in gearboxes, and the high quality of their product should represent a significant selling feature of CCM’s concrete mixers.

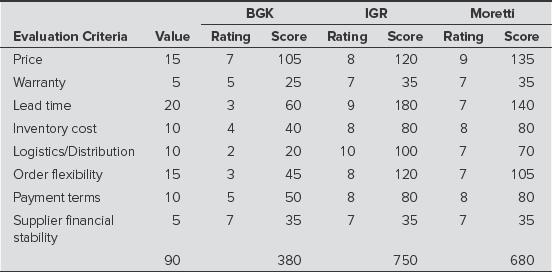

EXHIBIT 1 Supplier Evaluations

THE SUPPLIER SELECTION DECISION

Sarah had developed a supplier evaluation framework that ranked each supplier in eight areas: price, warranty (e.g., length of warranty), lead time, inventory costs (e.g., holding costs and need for safety stock), logistics/distribution (e.g., North American distribution capabilities), order flexibility (e.g., ability to make changes to orders), payment terms, and supplier financial stability. Each criterion was assigned a weight and suppliers were evaluated on a scale of 1 (poor) to 10 (excellent). Exhibit 1 provides a breakdown of Sarah’s rankings for the three suppliers.

As Sarah reviewed the data in the supplier evaluation framework, she wondered if it adequately represented the trade-offs among the three supply alternatives. Based on her analysis, IGR Industries would become the new gearbox supplier, which would mean ending their relationship with a supplier that had lasted more than three decades. She needed to finalize her recommendation before a planned conference call with Jon Del Rosario and the head of purchasing at the IMC plant in St. Louis the following week.

As Sarah Jenkins, what recommendations would you make regarding the selection of a gearbox supplier? Justify your recommendation.

BGK IGR Moretti Evaluation Criteria Value Rating Score Rating Score Rating Score Price 15 7 105 8. 120 6. 135 Warranty 5 5 25 7 35 7 35 Lead time 20 60 6. 180 140 Inventory cost 10 40 8. 80 8. 80 Logistics/Distribution 10 20 10 100 7 70 Order flexibility 15 3 45 8. 120 7 105 Payment terms 10 5 50 80 8 80 Supplier financial stability 7 35 35 7 35 90 380 750 680 LO

Step by Step Solution

3.31 Rating (148 Votes )

There are 3 Steps involved in it

Step: 1

Background BGK is a single source for both CCM and St Louis The current supplier BGK has reputation for superior quality and reliability But the products are typically more expensive than the competit...

Get Instant Access to Expert-Tailored Solutions

See step-by-step solutions with expert insights and AI powered tools for academic success

Step: 2

Step: 3

Document Format ( 1 attachment)

604f2d2a81edd_73398.docx

120 KBs Word File

Ace Your Homework with AI

Get the answers you need in no time with our AI-driven, step-by-step assistance

Get Started