Question

Assume the role of Aircraft Rescue and Fire Fighting (ARFF) Commander at the Bill and Hillary Clinton National Airport in Little Rock, Arkansas, USA. You

Assume the role of Aircraft Rescue and Fire Fighting (ARFF) Commander at the Bill and Hillary Clinton National Airport in Little Rock, Arkansas, USA. You will submit a briefing for the airport's upper management based on the following documents and information:

https://www.ntsb.gov/investigations/AccidentReports/Reports/AAR0102.pdf

Executive Summary

On June 1, 1999, at 2350:44 central daylight time, American Airlines flight 1420, a McDonnell Douglas DC-9-82 (MD-82), N215AA, crashed after it overran the end of runway 4R during landing at Little Rock National Airport in Little Rock, Arkansas. Flight 1420 departed from Dallas/Fort Worth International Airport, Texas, about 2240 with 2 flight crewmembers, 4 flight attendants, and 139 passengers aboard and touched down in Little Rock at 2350:20. After departing the end of the runway, the airplane struck several tubes extending outward from the left edge of the instrument landing system localizer array, located 411 feet beyond the end of the runway; passed through a chain link security fence and over a rock embankment to a flood plain, located approximately 15 feet below the runway elevation; and collided with the structure supporting the runway 22L approach lighting system. The captain and 10 passengers were killed; the first officer, the flight attendants, and 105 passengers received serious or minor injuries; and 24 passengers were not injured. The airplane was destroyed by impact forces and a postcrash fire. Flight 1420 was operating under the provisions of 14 Code of Federal Regulations Part 121 on an instrument flight rules flight plan. The National Transportation Safety Board determines that the probable causes of this accident were the flight crew's failure to discontinue the approach when severe thunderstorms and their associated hazards to flight operations had moved into the airport area and the crew's failure to ensure that the spoilers had extended after touchdown. Contributing to the accident were the flight crew's (1) impaired performance resulting from fatigue and the situational stress associated with the intent to land under the circumstances, (2) continuation of the approach to a landing when the company's maximum crosswind component was exceeded, and (3) use of reverse thrust greater than 1.3 engine pressure ratio after landing. The safety issues in this report focus on flight crew performance, flight crew decision-making regarding operations in adverse weather, pilot fatigue, weather information dissemination, emergency response, frangibility of airport structures, and Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) oversight. Safety recommendations concerning these issues are addressed to the FAA and the National Weather Service.

History of Flight

On June 1, 1999, at 2350:44 central daylight time,1 American Airlines flight 1420, a McDonnell Douglas DC-9-82 (MD-82), N215AA, crashed after it overran the end of runway 4R during landing at Little Rock National Airport in Little Rock, Arkansas. Flight 1420 departed from Dallas/Fort Worth International Airport, Texas, about 2240 with 2 flight crewmembers, 4 flight attendants, and 139 passengers aboard and touched down in Little Rock at 2350:20. After departing the end of the runway, the airplane struck several tubes extending outward from the left edge of the instrument landing system (ILS) localizer array, located 411 feet beyond the end of the runway; passed through a chain link security fence and over a rock embankment to a flood plain, located approximately 15 feet below the runway elevation; and collided with the structure supporting the runway 22L approach lighting system. The captain and 10 passengers were killed; the first officer, the flight attendants, and 105 passengers received serious or minor injuries; and 24 passengers were not injured.2 The airplane was destroyed by impact forces and a postcrash fire. Flight 1420 was operating under the provisions of 14 Code of Federal Regulations (CFR) Part 121 on an instrument flight rules (IFR) flight plan. Flight 1420 was the third and final leg of the first day of a 3-day sequence for the flight crew. The flight sequence began at O'Hare International Airport, Chicago, Illinois. According to American Airlines company records, the captain checked in for the flight about 1038, and the first officer checked in about 1018. Flight 1226, from Chicago to Salt Lake City International Airport, Utah, departed about 1143 and arrived about 1458 (1358 mountain daylight time). Flight 2080, from Salt Lake City to Dallas/Fort Worth, departed about 1647 (1547 mountain daylight time) and arrived about 2010, 39 minutes later than scheduled because of an airborne hold during the approach resulting from adverse weather in the airport area. The captain was the flying pilot for flight 1226, and the first officer was the flying pilot for flight 2080. Flight 1420, from Dallas/Fort Worth to Little Rock, was scheduled to depart about 2028 and arrive about 2141. However, before its arrival at Dallas/Fort Worth, the flight crew received an aircraft communication addressing and reporting system (ACARS)3 message indicating a delayed departure time of 2100 for flight 1420. After deplaning from flight 2080, the flight crew proceeded to the departure gate for flight 1420. The flight crew then received trip paperwork for the flight, which included an American Airlines weather advisory for a widely scattered area of thunderstorms along the planned route and two National Weather Service (NWS) in-flight weather advisories for an area of severe thunderstorms4 along the planned route.5 The airplane originally intended to be used for the flight was delayed in its arrival to Dallas/Fort Worth because of the adverse weather in the area. After 2100, the first officer notified gate agents that flight 1420 would need to depart by 2316 because of American's company duty time limitation.6 The first officer then telephoned the flight dispatcher to suggest that he get another airplane for the flight or cancel it.7 Afterward, the accident airplane, N215AA, was substituted for flight 1420. The flight's 2240 departure time was 2 hours 12 minutes later than the scheduled departure time. The captain was the flying pilot, and the first officer was the nonflying pilot. About 2254, the flight dispatcher sent the flight crew an ACARS message indicating that the weather around Little Rock might be a factor during the arrival. The dispatcher suggested that the flight crew expedite the arrival to beat the thunderstorms if possible, and the flight crew acknowledged this message. The first officer indicated, in a postaccident interview, that "there was no discussion of delaying or diverting the landing" because of the weather. According to the predeparture trip paperwork, two alternate airports—Nashville International Airport, Tennessee, and Dallas/Fort Worth— were specified as options in case a diversion was needed. Beginning about 2258, flight 1420 was handled by controllers from the Fort Worth Air Route Traffic Control Center (ARTCC). About 2304, the Fort Worth center broadcast NWS Convective SIGMET [significant meteorological information] weather advisory 15C for an area of severe thunderstorms that included the Little Rock airport area. The cockpit voice recorder (CVR) indicated that the flight crew had discussed the weather and the need to expedite the approach. At 2325:47, the captain stated, "we got to get over there quick." About 5 seconds later, the first officer said, "I don't like that...that's lightning," to which the captain replied, "sure is." The CVR also indicated that the flight crew had the city of Little Rock and the airport area in sight by at 2326:59. About 2327, the Fort Worth center cleared the flight to descend to 10,000 feet mean sea level (msl) and provided an altimeter setting of 29.86 inches of mercury (Hg). The flight was transferred about 2328 to the Memphis ARTCC, which provided the same altimeter setting.

According to the CVR, the flight crew contacted the Little Rock Air Traffic Control Tower (ATCT) at 2334:05. The controller advised the flight crew that a thunderstorm located northwest of the airport was moving through the area and that the wind was 280º at 28 knots gusting to 44 knots. The first officer told the controller that he and the captain could see the lightning. The controller told the flight crew to expect an ILS approach to runway 22L.9 The first officer indicated in a postaccident interview that, during the descent into the terminal area, the weather appeared to be about 15 miles away from the airport and that he and the captain thought that there was "some time" to make the approach. The CVR indicated that, between at 2336:04 and at 2336:13, the captain and first officer discussed American Airlines' crosswind limitation for landing. The captain indicated that 30 knots was the crosswind limitation but realized that he had provided the limitation for a dry runway. The captain then stated that the wet runway crosswind limitation was 20 knots, but the first officer stated that the limitation was 25 knots. In testimony at the National Transporation Safety Board's public hearing on this accident,10 the first officer stated that neither he nor the captain checked the actual crosswind limitation in American's flight manual. The first officer testified that he had taken the manual out but that the captain had signaled him to put the manual away because the captain was confident that the crosswind limitation was 20 knots.11 At 2339:00, the controller cleared the flight to descend to an altitude of 3,000 feet msl. The controller then asked the flight crew about the weather conditions along the runway 22L final approach course, stating his belief that the airplane's weather radar was "a lot better" than the weather radar depiction available in the tower. At 2339:12, the first officer stated, "okay, we can...see the airport from here. We can barely make it out but we should be able to make [runway] two two...that storm is moving this way like your radar says it is but a little bit farther off than you thought." The controller then offered flight 1420 a visual approach to the runway, but the first officer indicated, "at this point, we really can't make it out. We're gonna have to stay with you as long as possible."

https://www.aopa.org/destinations/airports/KLIT/details

8 Step Process for Managing a Hazardous Materials Response

Step 1: Site Management and Control GOAL: Establish the playing field so that all subsequent response operations can be implemented safely and efficiently.

--hot zone, perimeter, escape routes, ICP, PPE

Step 2: Identify the Problem GOAL: Identify the scope and nature of the problem, including the type and nature of the hazmat involved. Look for clues!

--containers, placards, materials, physical observations, hazards, interview

Step 3: Hazard Assessment and Risk Evaluation GOAL: Assess the hazard present, evaluate the level of risk, and establish an Incident Action Plan (IAP) to solve the problem.

--assess hazards and risks (offensive/defensiveon-intervention strategies) *Risk-based Response

Step 4: Select Personal Protective Clothing and Equipment GOAL: Ensure all emergency response personnel have the appropriate level of personal protective clothing and equipment for the expected tasks.

--the capabilities of the individuals using PPE needs to be considered —physiological and psychological stress

Step 5: Information Management & Resource Coordination GOAL: Timely and effective management, coordination and dissemination of data, info and resources among all players.

--internal and external, safety briefings, confirm orders, regular briefings to externals

Step 6: Implement Response Objectives GOAL: Ensure incident priorities (rescue, stabilization, environmental, etc.) are accomplished in a safe, timely, and effective manner.

--rescue, public protective actions, spill control, leak control, fire control, clean-up and recovery --hazard monitoring to see if conditions are changing

Step 7: Decon and Clean-

Up GOAL: Ensure the safety of both emergency responders and the public by reducing the level of contamination on-scene and minimizing the potential for secondary release beyond the scene.

--decon within the warm zone, upslope, and upwind of the site --proper disposal of haz waste

Step 8: Terminate the Incident GOAL: Ensure overall command is transferred to the proper agency and post-incident administrative activities are completed per local procedures.

--debrief, document, critique=improve --all disasters are local!

questions:

After reviewing the above resources, complete the following:

- Think about what obstacles your ARFF team encountered during this response.

- Describe your team's response and how the critical issues emerged as significant. Explain these issues clearly and concisely.

- Provide recommendations to upper management with solutions that will improve your team's future response and explain why these recommendations are "appropriate." Make a compelling case to help ensure your recommendations are accepted and can be implemented.

- In your written briefing to the airport's upper management, remember that they don't want to hear every little detail, so focus on only a few critical issues you think are the most important to communicate.

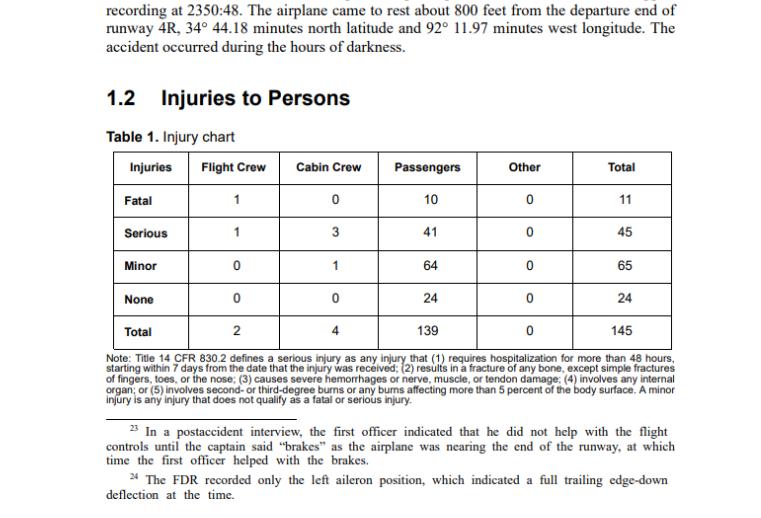

recording at 2350:48. The airplane came to rest about 800 feet from the departure end of runway 4R, 34 44.18 minutes north latitude and 92 11.97 minutes west longitude. The accident occurred during the hours of darkness. 1.2 Injuries to Persons Table 1. Injury chart Injuries Fatal Serious Minor Flight Crew None 1 1 Cabin Crew 0 0 3 Passengers 10 1 41 Other 0 0 45 64 0 65 0 0 24 0 24 Total 2 4 139 0 145 Note: Title 14 CFR 830.2 defines a serious injury as any injury that (1) requires hospitalization for more than 48 hours, starting within 7 days from the date that the injury was received; (2) results in a fracture of any bone, except simple fractures of fingers, toes, or the nose; (3) causes severe hemorrhages or nerve, muscle, or tendon damage: (4) involves any internal organ; or (5) involves second-or third-degree burns or any burns affecting more than 5 percent of the body surface. A minor injury is any injury that does not qualify as a fatal or serious injury. Total 11 23 In a postaccident interview, the first officer indicated that he did not help with the flight controls until the captain said "brakes" as the airplane was nearing the end of the runway, at which time the first officer helped with the brakes. The FDR recorded only the left aileron position, which indicated a full trailing edge-down deflection at the time.

Step by Step Solution

There are 3 Steps involved in it

Step: 1

Answer Briefing for Upper Management American Airlines Flight 1420 Response Review and Recommendations Dear Upper Management In the aftermath of the American Airlines Flight 1420 incident on June 1 19...

Get Instant Access to Expert-Tailored Solutions

See step-by-step solutions with expert insights and AI powered tools for academic success

Step: 2

Step: 3

Ace Your Homework with AI

Get the answers you need in no time with our AI-driven, step-by-step assistance

Get Started