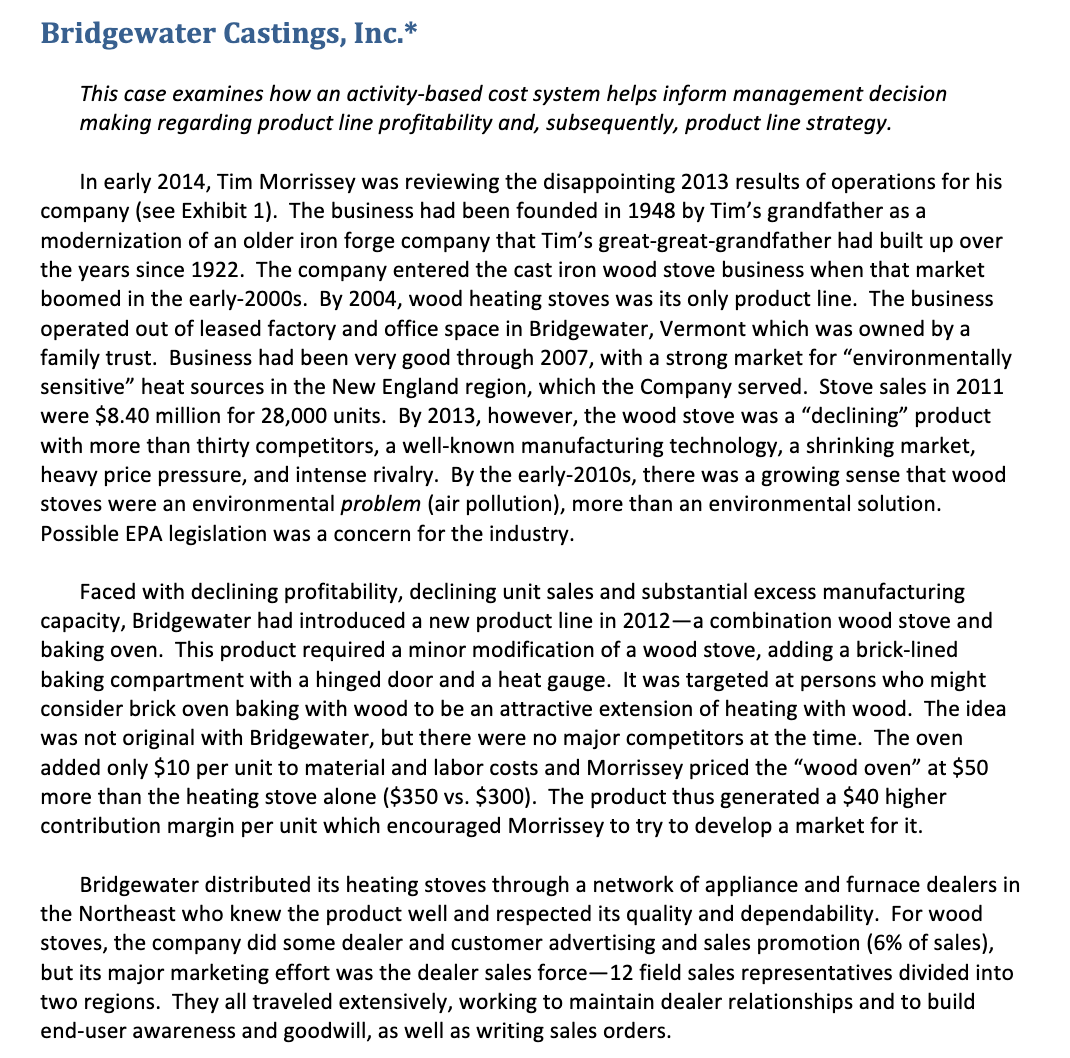

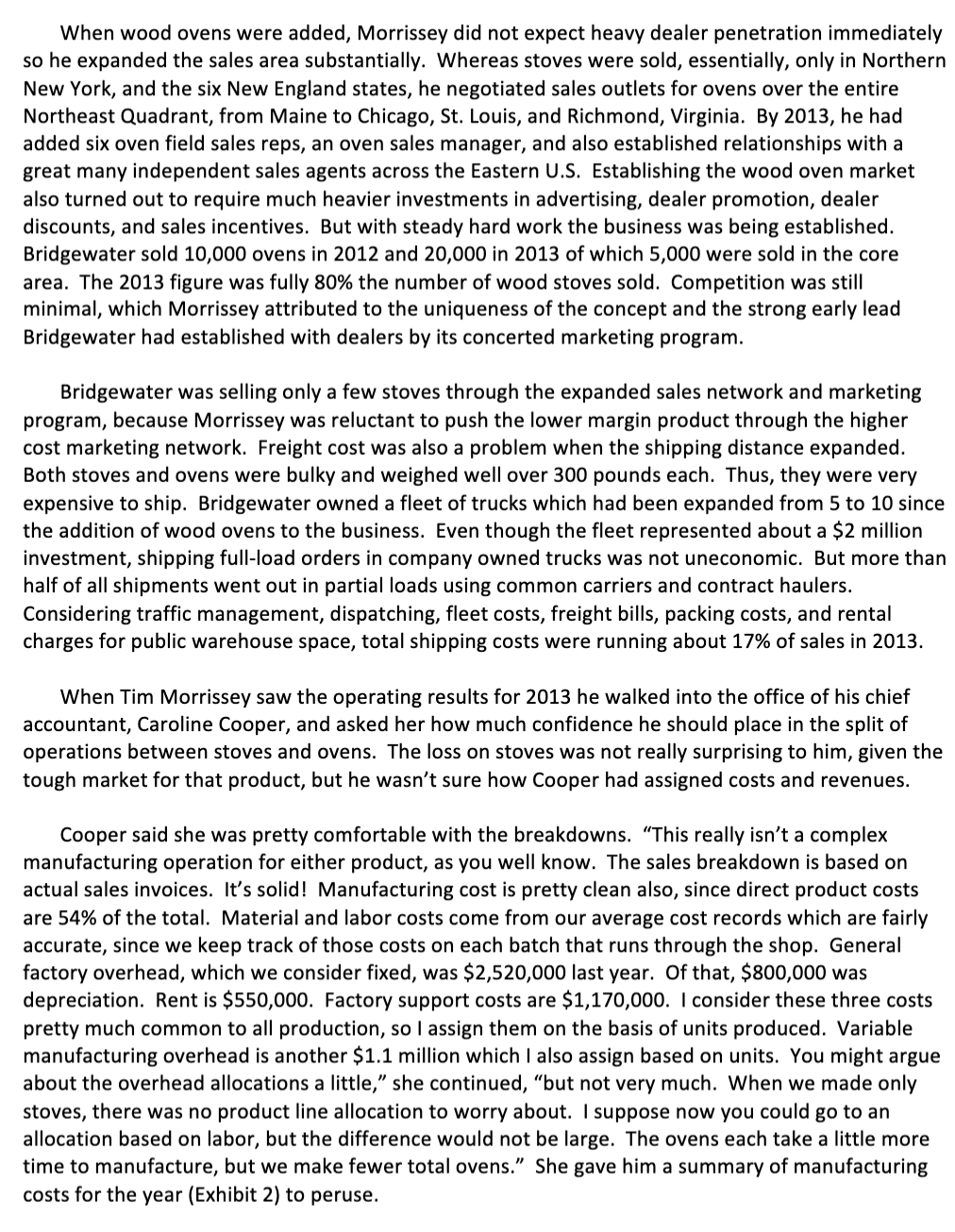

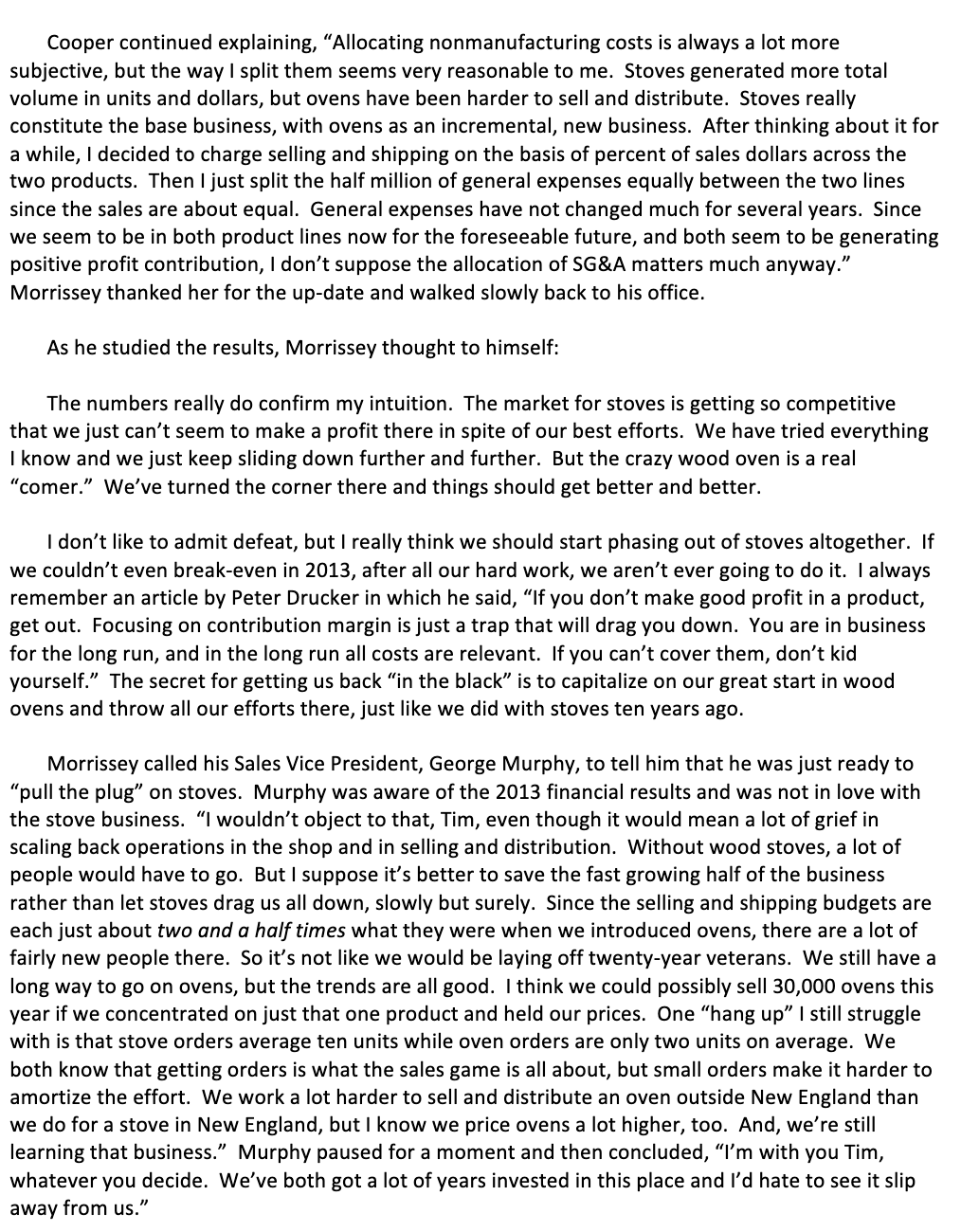

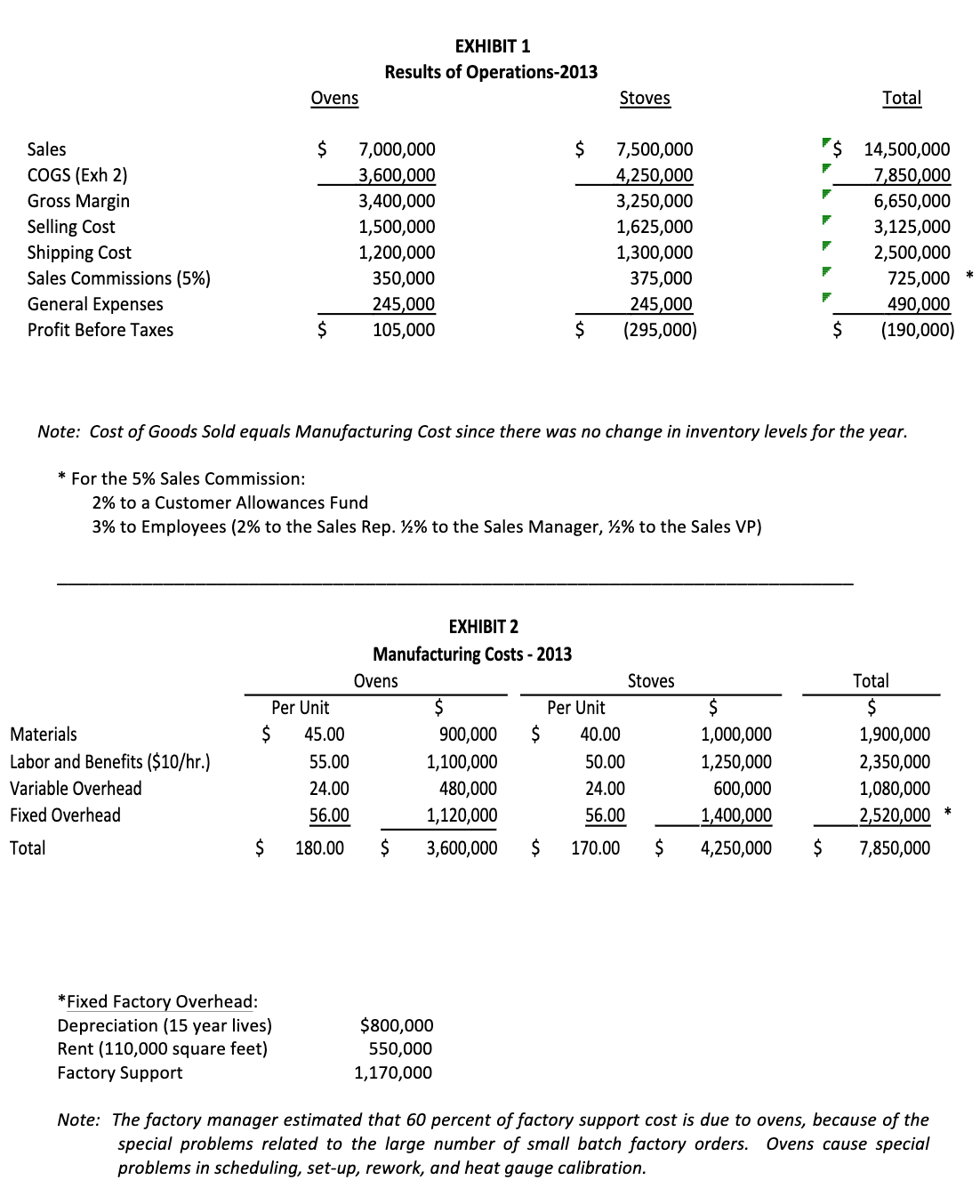

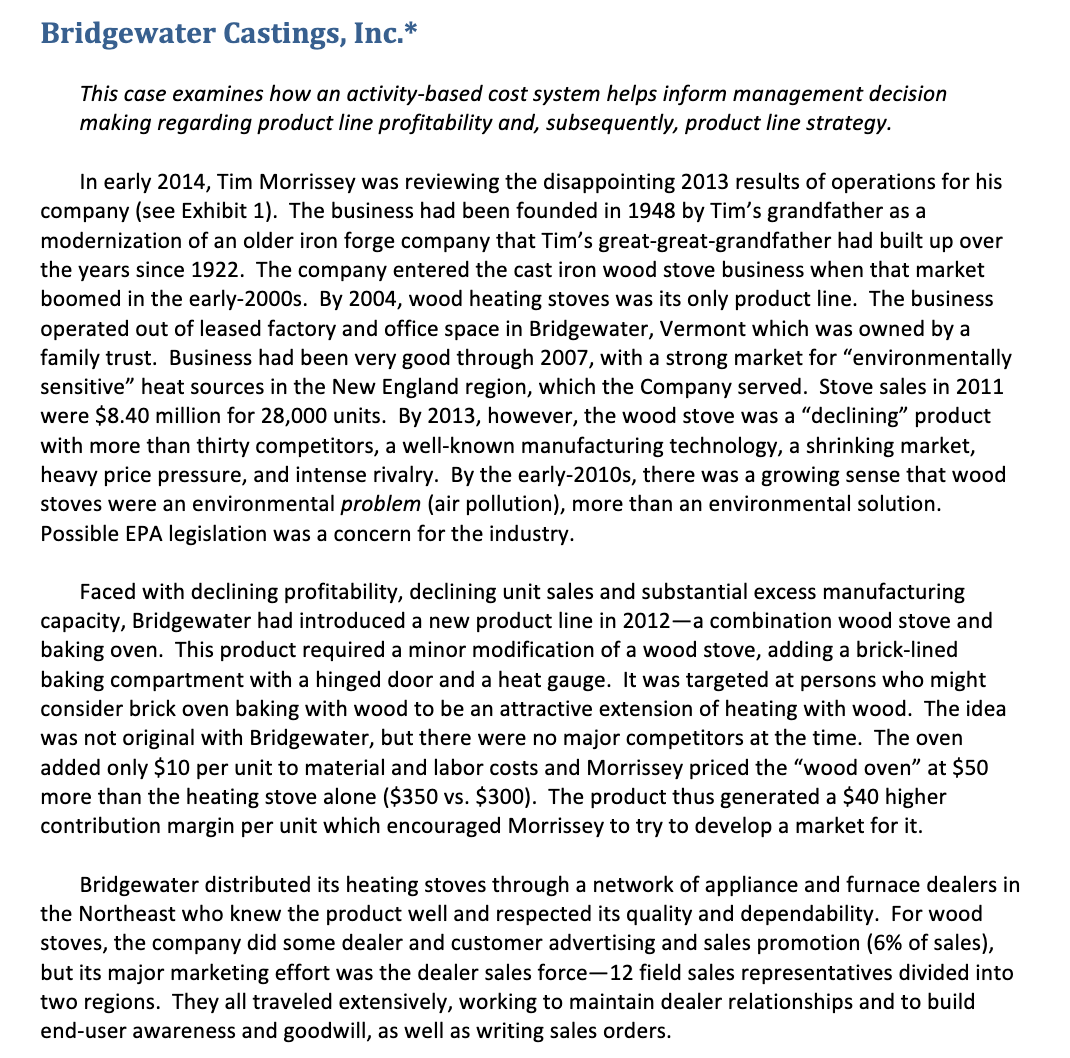

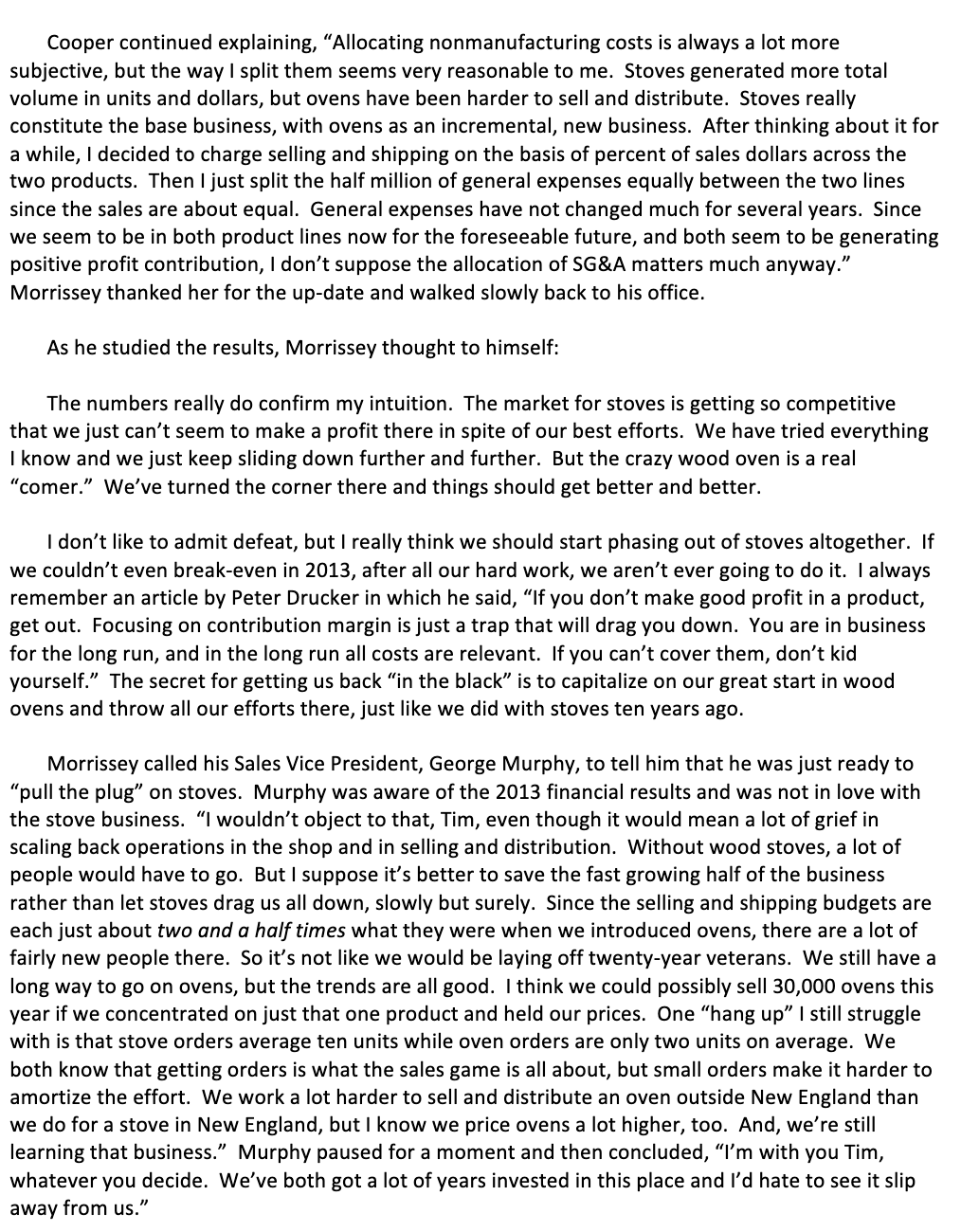

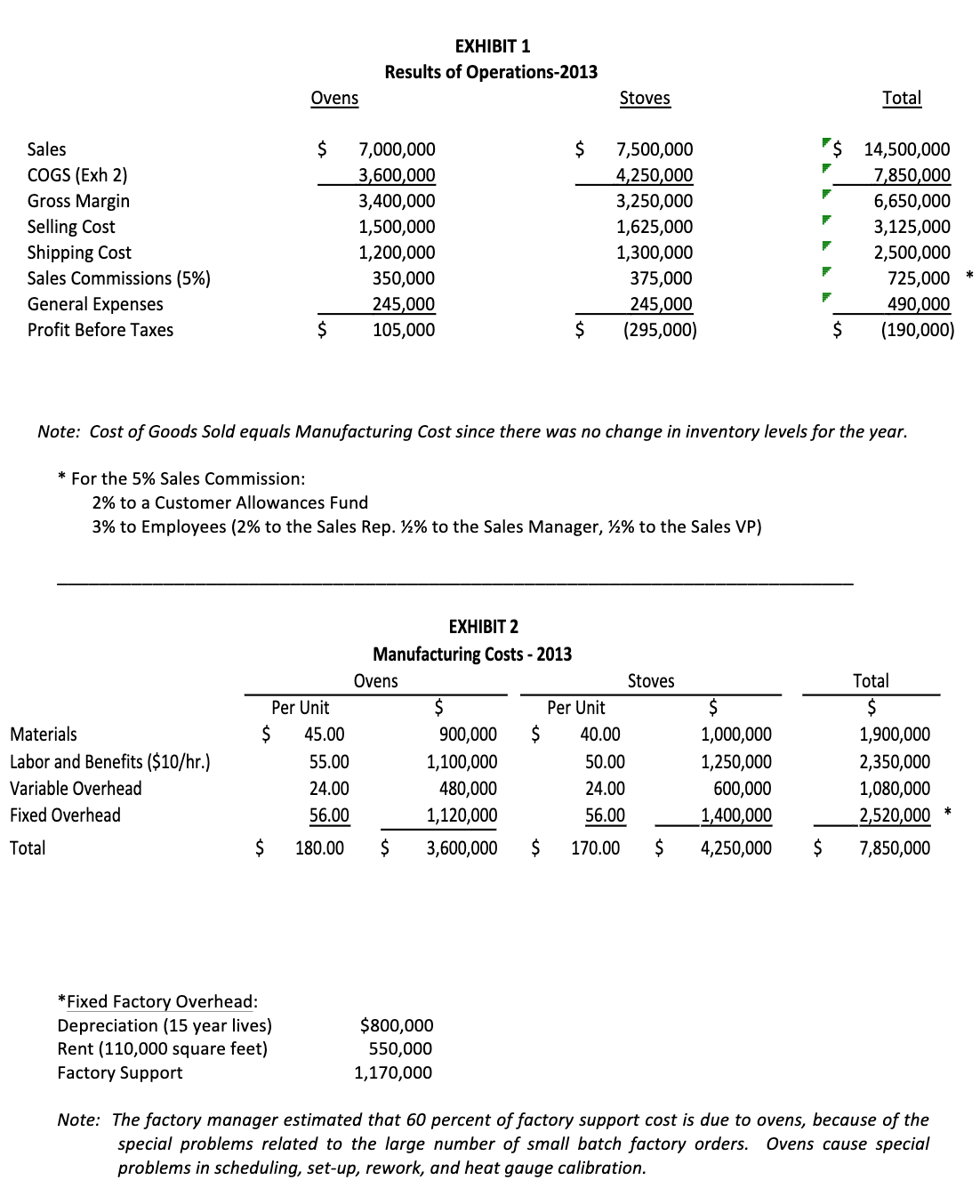

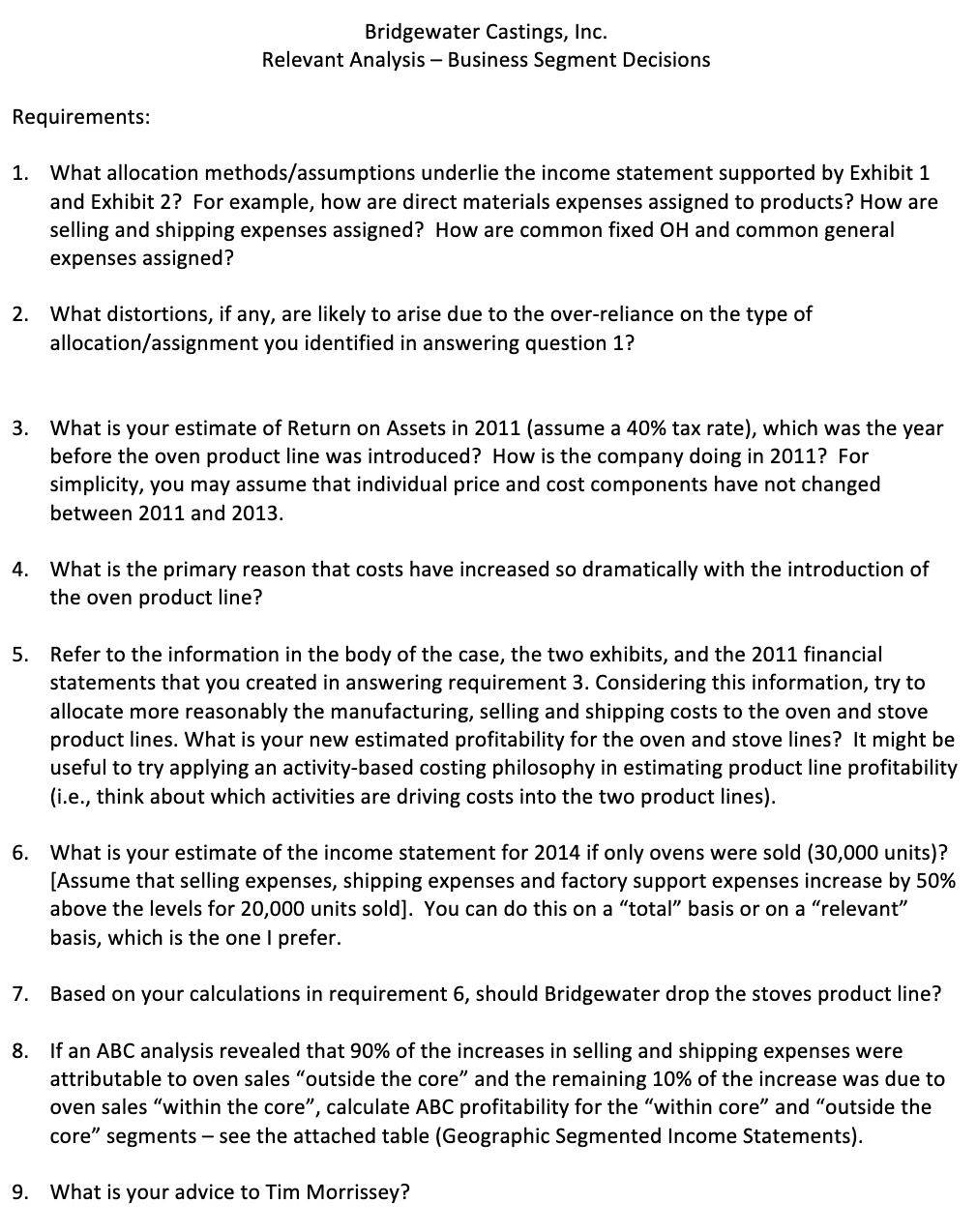

Bridgewater Castings, Inc.* This case examines how an activity-based cost system helps inform management decision making regarding product line profitability and, subsequently, product line strategy. In early 2014, Tim Morrissey was reviewing the disappointing 2013 results of operations for his company (see Exhibit 1). The business had been founded in 1948 by Tim's grandfather as a modernization of an older iron forge company that Tim's great-great-grandfather had built up over the years since 1922. The company entered the cast iron wood stove business when that market boomed in the early 2000s. By 2004, wood heating stoves was its only product line. The business operated out of leased factory and office space in Bridgewater, Vermont which was owned by a family trust. Business had been very good through 2007, with a strong market for "environmentally sensitive heat sources in the New England region, which the Company served. Stove sales in 2011 were $8.40 million for 28,000 units. By 2013, however, the wood stove was a "declining product with more than thirty competitors, a well-known manufacturing technology, a shrinking market, heavy price pressure, and intense rivalry. By the early-2010s, there was a growing sense that wood stoves were an environmental problem (air pollution), more than an environmental solution. Possible EPA legislation was a concern for the industry. Faced with declining profitability, declining unit sales and substantial excess manufacturing capacity, Bridgewater had introduced a new product line in 2012-a combination wood stove and baking oven. This product required a minor modification of a wood stove, adding a brick-lined baking compartment with a hinged door and a heat gauge. It was targeted at persons who might consider brick oven baking with wood to be an attractive extension of heating with wood. The idea was not original with Bridgewater, but there were no major competitors at the time. The oven added only $10 per unit to material and labor costs and Morrissey priced the "wood oven" at $50 more than the heating stove alone ($350 vs. $300). The product thus generated a $40 higher contribution margin per unit which encouraged Morrissey to try to develop a market for it. Bridgewater distributed its heating stoves through a network of appliance and furnace dealers in the Northeast who knew the product well and respected its quality and dependability. For wood stoves, the company did some dealer and customer advertising and sales promotion (6% of sales), but its major marketing effort was the dealer sales force-12 field sales representatives divided into two regions. They all traveled extensively, working to maintain dealer relationships and to build end-user awareness and goodwill, as well as writing sales orders. When wood ovens were added, Morrissey did not expect heavy dealer penetration immediately so he expanded the sales area substantially. Whereas stoves were sold, essentially, only in Northern New York, and the six New England states, he negotiated sales outlets for ovens over the entire Northeast Quadrant, from Maine to Chicago, St. Louis, and Richmond, Virginia. By 2013, he had added six oven field sales reps, an oven sales manager, and also established relationships with a great many independent sales agents across the Eastern U.S. Establishing the wood oven market also turned out to require much heavier investments in advertising, dealer promotion, dealer discounts, and sales incentives. But with steady hard work the business was being established. Bridgewater sold 10,000 ovens in 2012 and 20,000 in 2013 of which 5,000 were sold in the core area. The 2013 figure was fully 80% the number of wood stoves sold. Competition was still minimal, which Morrissey attributed to the uniqueness of the concept and the strong early lead Bridgewater had established with dealers by its concerted marketing program. Bridgewater was selling only a few stoves through the expanded sales network and marketing program, because Morrissey was reluctant to push the lower margin product through the higher cost marketing network. Freight cost was also a problem when the shipping distance expanded. Both stoves and ovens were bulky and weighed well over 300 pounds each. Thus, they were very expensive to ship. Bridgewater owned a fleet of trucks which had been expanded from 5 to 10 since the addition of wood ovens to the business. Even though the fleet represented about a $2 million investment, shipping full-load orders in company owned trucks was not uneconomic. But more than half of all shipments went out in partial loads using common carriers and contract haulers. Considering traffic management, dispatching, fleet costs, freight bills, packing costs, and rental charges for public warehouse space, total shipping costs were running about 17% of sales in 2013. When Tim Morrissey saw the operating results for 2013 he walked into the office of his chief accountant, Caroline Cooper, and asked her how much confidence he should place in the split of operations between stoves and ovens. The loss on stoves was not really surprising to him, given the tough market for that product, but he wasn't sure how Cooper had assigned costs and revenues. Cooper said she was pretty comfortable with the breakdowns. This really isn't a complex manufacturing operation for either product, as you well know. The sales breakdown is based on actual sales invoices. It's solid! Manufacturing cost is pretty clean also, since direct product costs are 54% of the total. Material and labor costs come from our average cost records which are fairly accurate, since we keep track of those costs on each batch that runs through the shop. General factory overhead, which we consider fixed, was $2,520,000 last year. Of that, $800,000 was depreciation. Rent is $550,000. Factory support costs are $1,170,000. I consider these three costs pretty much common to all production, so I assign them on the basis of units produced. Variable manufacturing overhead is another $1.1 million which I also assign based on units. You might argue about the overhead allocations a little, she continued, but not very much. When we made only stoves, there was no product line allocation to worry about. I suppose now you could go to an allocation based on labor, but the difference would not be large. The ovens each take a little more time to manufacture, but we make fewer total ovens. She gave him a summary of manufacturing costs for the year (Exhibit 2) to peruse. Cooper continued explaining, Allocating nonmanufacturing costs is always a lot more subjective, but the way I split them seems very reasonable to me. Stoves generated more total volume in units and dollars, but ovens have been harder to sell and distribute. Stoves really constitute the base business, with ovens as an incremental, new business. After thinking about it for a while, I decided to charge selling and shipping on the basis of percent of sales dollars across the two products. Then I just split the half million of general expenses equally between the two lines since the sales are about equal. General expenses have not changed much for several years. Since we seem to be in both product lines now for the foreseeable future, and both seem to be generating positive profit contribution, I don't suppose the allocation of SG&A matters much anyway." Morrissey thanked her for the up-date and walked slowly back to his office. As he studied the results, Morrissey thought to himself: The numbers really do confirm my intuition. The market for stoves is getting so competitive that we just can't seem to make a profit there in spite of our best efforts. We have tried everything I know and we just keep sliding down further and further. But the crazy wood oven is a real "comer. We've turned the corner there and things should get better and better. I don't like to admit defeat, but I really think we should start phasing out of stoves altogether. If we couldn't even break-even in 2013, after all our hard work, we aren't ever going to do it. I always remember an article by Peter Drucker in which he said, If you don't make good profit in a product, get out. Focusing on contribution margin is just a trap that will drag you down. You are in business for the long run, and in the long run all costs are relevant. If you can't cover them, don't kid yourself. The secret for getting us back in the black is to capitalize on our great start in wood ovens and throw all our efforts there, just like we did with stoves ten years ago. Morrissey called his Sales Vice President, George Murphy, to tell him that he was just ready to "pull the plug" on stoves. Murphy was aware of the 2013 financial results and was not in love with the stove business. I wouldn't object to that, Tim, even though it would mean a lot of grief in scaling back operations in the shop and in selling and distribution. Without wood stoves, a lot of people would have to go. But I suppose it's better to save the fast growing half of the business rather than let stoves drag us all down, slowly but surely. Since the selling and shipping budgets are each just about two and a half times what they were when we introduced ovens, there are a lot of fairly new people there. So it's not like we would be laying off twenty-year veterans. We still have a long way to go on ovens, but the trends are all good. I think we could possibly sell 30,000 ovens this year if we concentrated on just that one product and held our prices. One "hang up" I still struggle with is that stove orders average ten units while oven orders are only two units on average. We both know that getting orders is what the sales game is all about, but small orders make it harder to amortize the effort. We work a lot harder to sell and distribute an oven outside New England than we do for a stove in New England, but I know we price ovens a lot higher, too. And, we're still learning that business. Murphy paused for a moment and then concluded, I'm with you Tim, whatever you decide. We've both got a lot of years invested in this place and I'd hate to see it slip away from us." EXHIBIT 1 Results of Operations-2013 Ovens Stoves Total $ $ Sales COGS (Exh 2) Gross Margin Selling Cost Shipping Cost Sales Commissions (5%) General Expenses Profit Before Taxes 7,000,000 3,600,000 3,400,000 1,500,000 1,200,000 350,000 245,000 105,000 7,500,000 4,250,000 3,250,000 1,625,000 1,300,000 375,000 245,000 (295,000) $ 14,500,000 7,850,000 6,650,000 3,125,000 2,500,000 725,000 490,000 $ (190,000) $ $ Note: Cost of Goods Sold equals Manufacturing Cost since there was no change in inventory levels for the year. * For the 5% Sales Commission: 2% to a Customer Allowances Fund 3% to Employees (2% to the Sales Rep. 7% to the Sales Manager, 7% to the Sales VP) Materials Labor and Benefits ($10/hr.) Variable Overhead Fixed Overhead EXHIBIT 2 Manufacturing Costs - 2013 Ovens Stoves Per Unit $ Per Unit $ 45.00 900,000 $ 40.00 55.00 1,100,000 50.00 24.00 480,000 24.00 56.00 1,120,000 56.00 $ 180.00 $ 3,600,000 $ 170.00 $ $ 1,000,000 1,250,000 600,000 1,400,000 Total $ 1,900,000 2,350,000 1,080,000 2,520,000 7,850,000 Total 4,250,000 $ *Fixed Factory Overhead: Depreciation (15 year lives) Rent (110,000 square feet) Factory Support $800,000 550,000 1,170,000 Note: The factory manager estimated that 60 percent of factory support cost is due to ovens, because of the special problems related to the large number of small batch factory orders. Ovens cause special problems in scheduling, set-up, rework, and heat gauge calibration. Bridgewater Castings, Inc. Relevant Analysis Business Segment Decisions Requirements: 1. What allocation methods/assumptions underlie the income statement supported by Exhibit 1 and Exhibit 2? For example, how are direct materials expenses assigned to products? How are selling and shipping expenses assigned? How are common fixed OH and common general expenses assigned? 2. What distortions, if any, are likely to arise due to the over-reliance on the type of allocation/assignment you identified in answering question 1? 3. What is your estimate of Return on Assets in 2011 (assume a 40% tax rate), which was the year before the oven product line was introduced? How is the company doing in 2011? For simplicity, you may assume that individual price and cost components have not changed between 2011 and 2013. 4. What is the primary reason that costs have increased so dramatically with the introduction of the oven product line? 5. Refer to the information in the body of the case, the two exhibits, and the 2011 financial statements that you created in answering requirement 3. Considering this information, try to allocate more reasonably the manufacturing, selling and shipping costs to the oven and stove product lines. What is your new estimated profitability for the oven and stove lines? It might be useful to try applying an activity-based costing philosophy in estimating product line profitability (i.e., think about which activities are driving costs into the two product lines). 6. What is your estimate of the income statement for 2014 if only ovens were sold (30,000 units)? [Assume that selling expenses, shipping expenses and factory support expenses increase by 50% above the levels for 20,000 units sold). You can do this on a "total basis or on a "relevant" basis, which is the one I prefer. 7. Based on your calculations in requirement 6, should Bridgewater drop the stoves product line? 8. If an ABC analysis revealed that 90% of the increases in selling and shipping expenses were attributable to oven sales "outside the core" and the remaining 10% of the increase was due to oven sales "within the core, calculate ABC profitability for the "within core" and "outside the core segments see the attached table (Geographic Segmented Income Statements). 9. What is your advice to Tim Morrissey? Bridgewater Castings, Inc.* This case examines how an activity-based cost system helps inform management decision making regarding product line profitability and, subsequently, product line strategy. In early 2014, Tim Morrissey was reviewing the disappointing 2013 results of operations for his company (see Exhibit 1). The business had been founded in 1948 by Tim's grandfather as a modernization of an older iron forge company that Tim's great-great-grandfather had built up over the years since 1922. The company entered the cast iron wood stove business when that market boomed in the early 2000s. By 2004, wood heating stoves was its only product line. The business operated out of leased factory and office space in Bridgewater, Vermont which was owned by a family trust. Business had been very good through 2007, with a strong market for "environmentally sensitive heat sources in the New England region, which the Company served. Stove sales in 2011 were $8.40 million for 28,000 units. By 2013, however, the wood stove was a "declining product with more than thirty competitors, a well-known manufacturing technology, a shrinking market, heavy price pressure, and intense rivalry. By the early-2010s, there was a growing sense that wood stoves were an environmental problem (air pollution), more than an environmental solution. Possible EPA legislation was a concern for the industry. Faced with declining profitability, declining unit sales and substantial excess manufacturing capacity, Bridgewater had introduced a new product line in 2012-a combination wood stove and baking oven. This product required a minor modification of a wood stove, adding a brick-lined baking compartment with a hinged door and a heat gauge. It was targeted at persons who might consider brick oven baking with wood to be an attractive extension of heating with wood. The idea was not original with Bridgewater, but there were no major competitors at the time. The oven added only $10 per unit to material and labor costs and Morrissey priced the "wood oven" at $50 more than the heating stove alone ($350 vs. $300). The product thus generated a $40 higher contribution margin per unit which encouraged Morrissey to try to develop a market for it. Bridgewater distributed its heating stoves through a network of appliance and furnace dealers in the Northeast who knew the product well and respected its quality and dependability. For wood stoves, the company did some dealer and customer advertising and sales promotion (6% of sales), but its major marketing effort was the dealer sales force-12 field sales representatives divided into two regions. They all traveled extensively, working to maintain dealer relationships and to build end-user awareness and goodwill, as well as writing sales orders. When wood ovens were added, Morrissey did not expect heavy dealer penetration immediately so he expanded the sales area substantially. Whereas stoves were sold, essentially, only in Northern New York, and the six New England states, he negotiated sales outlets for ovens over the entire Northeast Quadrant, from Maine to Chicago, St. Louis, and Richmond, Virginia. By 2013, he had added six oven field sales reps, an oven sales manager, and also established relationships with a great many independent sales agents across the Eastern U.S. Establishing the wood oven market also turned out to require much heavier investments in advertising, dealer promotion, dealer discounts, and sales incentives. But with steady hard work the business was being established. Bridgewater sold 10,000 ovens in 2012 and 20,000 in 2013 of which 5,000 were sold in the core area. The 2013 figure was fully 80% the number of wood stoves sold. Competition was still minimal, which Morrissey attributed to the uniqueness of the concept and the strong early lead Bridgewater had established with dealers by its concerted marketing program. Bridgewater was selling only a few stoves through the expanded sales network and marketing program, because Morrissey was reluctant to push the lower margin product through the higher cost marketing network. Freight cost was also a problem when the shipping distance expanded. Both stoves and ovens were bulky and weighed well over 300 pounds each. Thus, they were very expensive to ship. Bridgewater owned a fleet of trucks which had been expanded from 5 to 10 since the addition of wood ovens to the business. Even though the fleet represented about a $2 million investment, shipping full-load orders in company owned trucks was not uneconomic. But more than half of all shipments went out in partial loads using common carriers and contract haulers. Considering traffic management, dispatching, fleet costs, freight bills, packing costs, and rental charges for public warehouse space, total shipping costs were running about 17% of sales in 2013. When Tim Morrissey saw the operating results for 2013 he walked into the office of his chief accountant, Caroline Cooper, and asked her how much confidence he should place in the split of operations between stoves and ovens. The loss on stoves was not really surprising to him, given the tough market for that product, but he wasn't sure how Cooper had assigned costs and revenues. Cooper said she was pretty comfortable with the breakdowns. This really isn't a complex manufacturing operation for either product, as you well know. The sales breakdown is based on actual sales invoices. It's solid! Manufacturing cost is pretty clean also, since direct product costs are 54% of the total. Material and labor costs come from our average cost records which are fairly accurate, since we keep track of those costs on each batch that runs through the shop. General factory overhead, which we consider fixed, was $2,520,000 last year. Of that, $800,000 was depreciation. Rent is $550,000. Factory support costs are $1,170,000. I consider these three costs pretty much common to all production, so I assign them on the basis of units produced. Variable manufacturing overhead is another $1.1 million which I also assign based on units. You might argue about the overhead allocations a little, she continued, but not very much. When we made only stoves, there was no product line allocation to worry about. I suppose now you could go to an allocation based on labor, but the difference would not be large. The ovens each take a little more time to manufacture, but we make fewer total ovens. She gave him a summary of manufacturing costs for the year (Exhibit 2) to peruse. Cooper continued explaining, Allocating nonmanufacturing costs is always a lot more subjective, but the way I split them seems very reasonable to me. Stoves generated more total volume in units and dollars, but ovens have been harder to sell and distribute. Stoves really constitute the base business, with ovens as an incremental, new business. After thinking about it for a while, I decided to charge selling and shipping on the basis of percent of sales dollars across the two products. Then I just split the half million of general expenses equally between the two lines since the sales are about equal. General expenses have not changed much for several years. Since we seem to be in both product lines now for the foreseeable future, and both seem to be generating positive profit contribution, I don't suppose the allocation of SG&A matters much anyway." Morrissey thanked her for the up-date and walked slowly back to his office. As he studied the results, Morrissey thought to himself: The numbers really do confirm my intuition. The market for stoves is getting so competitive that we just can't seem to make a profit there in spite of our best efforts. We have tried everything I know and we just keep sliding down further and further. But the crazy wood oven is a real "comer. We've turned the corner there and things should get better and better. I don't like to admit defeat, but I really think we should start phasing out of stoves altogether. If we couldn't even break-even in 2013, after all our hard work, we aren't ever going to do it. I always remember an article by Peter Drucker in which he said, If you don't make good profit in a product, get out. Focusing on contribution margin is just a trap that will drag you down. You are in business for the long run, and in the long run all costs are relevant. If you can't cover them, don't kid yourself. The secret for getting us back in the black is to capitalize on our great start in wood ovens and throw all our efforts there, just like we did with stoves ten years ago. Morrissey called his Sales Vice President, George Murphy, to tell him that he was just ready to "pull the plug" on stoves. Murphy was aware of the 2013 financial results and was not in love with the stove business. I wouldn't object to that, Tim, even though it would mean a lot of grief in scaling back operations in the shop and in selling and distribution. Without wood stoves, a lot of people would have to go. But I suppose it's better to save the fast growing half of the business rather than let stoves drag us all down, slowly but surely. Since the selling and shipping budgets are each just about two and a half times what they were when we introduced ovens, there are a lot of fairly new people there. So it's not like we would be laying off twenty-year veterans. We still have a long way to go on ovens, but the trends are all good. I think we could possibly sell 30,000 ovens this year if we concentrated on just that one product and held our prices. One "hang up" I still struggle with is that stove orders average ten units while oven orders are only two units on average. We both know that getting orders is what the sales game is all about, but small orders make it harder to amortize the effort. We work a lot harder to sell and distribute an oven outside New England than we do for a stove in New England, but I know we price ovens a lot higher, too. And, we're still learning that business. Murphy paused for a moment and then concluded, I'm with you Tim, whatever you decide. We've both got a lot of years invested in this place and I'd hate to see it slip away from us." EXHIBIT 1 Results of Operations-2013 Ovens Stoves Total $ $ Sales COGS (Exh 2) Gross Margin Selling Cost Shipping Cost Sales Commissions (5%) General Expenses Profit Before Taxes 7,000,000 3,600,000 3,400,000 1,500,000 1,200,000 350,000 245,000 105,000 7,500,000 4,250,000 3,250,000 1,625,000 1,300,000 375,000 245,000 (295,000) $ 14,500,000 7,850,000 6,650,000 3,125,000 2,500,000 725,000 490,000 $ (190,000) $ $ Note: Cost of Goods Sold equals Manufacturing Cost since there was no change in inventory levels for the year. * For the 5% Sales Commission: 2% to a Customer Allowances Fund 3% to Employees (2% to the Sales Rep. 7% to the Sales Manager, 7% to the Sales VP) Materials Labor and Benefits ($10/hr.) Variable Overhead Fixed Overhead EXHIBIT 2 Manufacturing Costs - 2013 Ovens Stoves Per Unit $ Per Unit $ 45.00 900,000 $ 40.00 55.00 1,100,000 50.00 24.00 480,000 24.00 56.00 1,120,000 56.00 $ 180.00 $ 3,600,000 $ 170.00 $ $ 1,000,000 1,250,000 600,000 1,400,000 Total $ 1,900,000 2,350,000 1,080,000 2,520,000 7,850,000 Total 4,250,000 $ *Fixed Factory Overhead: Depreciation (15 year lives) Rent (110,000 square feet) Factory Support $800,000 550,000 1,170,000 Note: The factory manager estimated that 60 percent of factory support cost is due to ovens, because of the special problems related to the large number of small batch factory orders. Ovens cause special problems in scheduling, set-up, rework, and heat gauge calibration. Bridgewater Castings, Inc. Relevant Analysis Business Segment Decisions Requirements: 1. What allocation methods/assumptions underlie the income statement supported by Exhibit 1 and Exhibit 2? For example, how are direct materials expenses assigned to products? How are selling and shipping expenses assigned? How are common fixed OH and common general expenses assigned? 2. What distortions, if any, are likely to arise due to the over-reliance on the type of allocation/assignment you identified in answering question 1? 3. What is your estimate of Return on Assets in 2011 (assume a 40% tax rate), which was the year before the oven product line was introduced? How is the company doing in 2011? For simplicity, you may assume that individual price and cost components have not changed between 2011 and 2013. 4. What is the primary reason that costs have increased so dramatically with the introduction of the oven product line? 5. Refer to the information in the body of the case, the two exhibits, and the 2011 financial statements that you created in answering requirement 3. Considering this information, try to allocate more reasonably the manufacturing, selling and shipping costs to the oven and stove product lines. What is your new estimated profitability for the oven and stove lines? It might be useful to try applying an activity-based costing philosophy in estimating product line profitability (i.e., think about which activities are driving costs into the two product lines). 6. What is your estimate of the income statement for 2014 if only ovens were sold (30,000 units)? [Assume that selling expenses, shipping expenses and factory support expenses increase by 50% above the levels for 20,000 units sold). You can do this on a "total basis or on a "relevant" basis, which is the one I prefer. 7. Based on your calculations in requirement 6, should Bridgewater drop the stoves product line? 8. If an ABC analysis revealed that 90% of the increases in selling and shipping expenses were attributable to oven sales "outside the core" and the remaining 10% of the increase was due to oven sales "within the core, calculate ABC profitability for the "within core" and "outside the core segments see the attached table (Geographic Segmented Income Statements). 9. What is your advice to Tim Morrissey