Can you please explain and show work so I can understand. I have attached article for reference.

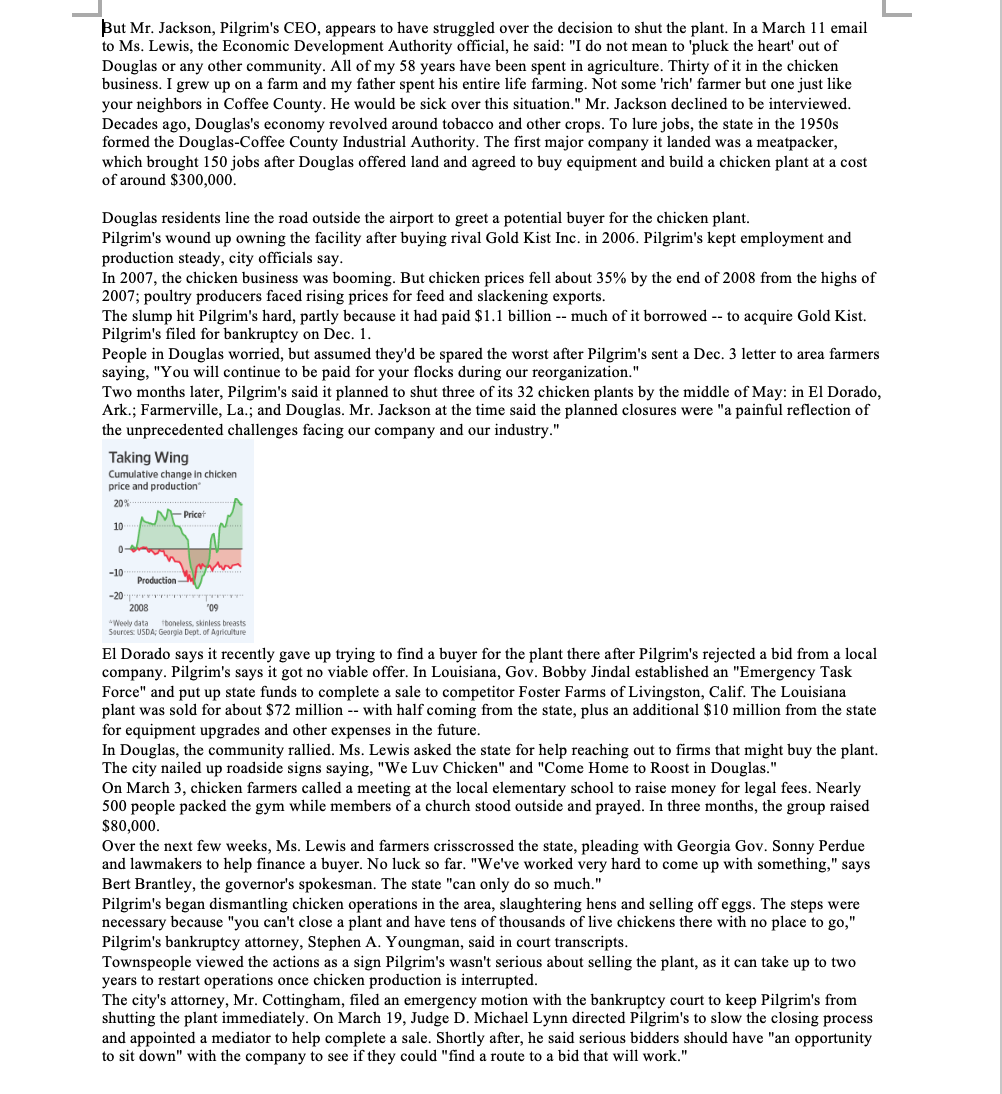

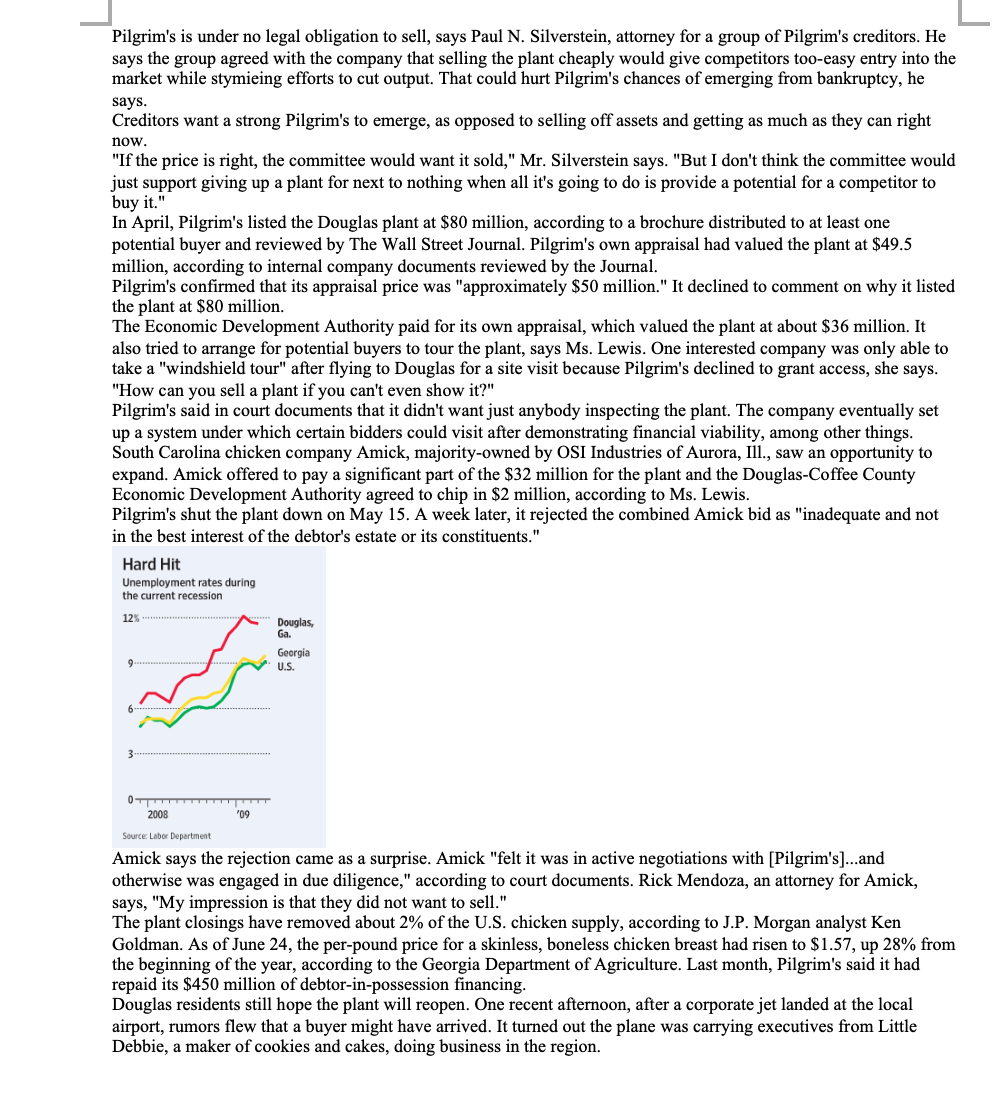

45. 47. Short Answer Questions and related True or False: . A past article In the Wall Street Journal described the situation surrounding the closure of a chicken processing plant by Pilgrim's Prlde, a chicken processor that was operating under bankmptcy protection at the time the article was written. There was a controversy over whether Pllgrlm's Pride was making a serious effort to nd a buyer for the plant In Georgia. The company claimed It was while local farmers and workers claim It was not. As evidence of the lack of good faith, locals cited Pilgrim's dismantling of chicken operations In the area, slaughtering hens and selling off eggs. Pilgrim claimed the steps were necessary because "you can't close a plant and have tens of thousands of live chickens there with no place to go." Townspeople viewed the actions as a sign Pilgrim's wasn't serious about selling the plant, as it can take up to two years to restart operations once chicken production ls Interrupted. In economic terms, for this plant two years is the \"long term". True or false and briefly explain your answer.] The processing plant was not operating at the time the article was written and the sheds where the chickens are raised were not in use. The article reads: \"A group of Douglas chicken farmers gathered outside an empty chicken house in Douglas, Ga. With no plantto process the birds they raise, local chicken farmers have no income to pay off debts. Months ago, the hundreds of cavernous, metal-and-wood chicken houses In the county were worth at least $200,000 each when filled with chickens, farmers say. Now, except for les and old feathers, the structures sit empty." It can be concluded from the quotes that the chicken facilities In the town have \"exited" the industry. True or false and briefly explain your answer. . An excerpt from the article reads: "In 2007, the chicken business was booming. But chicken prices fell about 35% by the end of 2008 from the highs of 2007; poultry producers faced rising prices for feed and slackening exports." The higher feed prices would have shifted the chicken producers' marginal cost curve up or to the IefL] True False [no explanation needed] From the excerpt quoted In question 46, it can be concluded that chlcken prices fell in 2003 due to the changing marginal cost curve. True False [no explanation needed] _I I At Chicken Plant, a Recession Battle By LAUREN E'ITER The Wall Street Journal June 30, 2009 DOUGLAS, Ga. This small town was devastated in February when its largest employer, Pilgrim's Pride Corp., said it would close a chicken-processing plant as part of the company's bankruptcy ling. Since th:, city and county ofcials have be: working to nd a buyer who could save the plant's nearly 1,000 jobs and .53 00,000 in annual county tax revenues. But there's a problem: Pilgrim's Pride isn't eager to sell. The standoff shows how two important imperatives in a recession creating jobs and cutting excess capacity -- can collide. Pilgrim's has so far rejected a $32 million bid for the plant from Amick Farms LLC of Batesburg, S.C., company and city ofcials say. Another chicken company took a look and decided Pilgrim's asking price was too high, say people familiar with the matter. City ofcials say the company kept a prospective bidder from touring the plant, making it a challenge to market. A sign placed around Douglas County, Ga., to encourage investment. "We've played by the book," says JoAnne Lewis, executive director of the Douglas-Coffee County Economic Development Authority. But \"there has be: no meeting in the middle. We feel like we're part of a giant game." Pilgrim's says it hasn't be: offered a fair price for the plant and is cautious about letting rivals see its manufacturing processes. Company emails and court documents suggest the Pittsburg, Texas-based company also is concerned about adding capacity in an already struggling industry. In an email to the city of Douglas, Pilgrim's President and Chief Executive Don Jackson said, "With declining demand for chicken in this terrible economy we need to remove chicken om the market. This would not be accomplished with a sale." While he said he recognized the "devastating impact" a closing would have on Douglas, "the actions do strengthen the company and help protect the jobs" of the company's 40,000 U.S. employees and farmers. Pilgrim's said, in a statem:t, the closures were necessary because it had a loss of nearly $1 billion in 2008 and a loss of $229 million in the rst quarter of scal 2009. \"It is a tragic situation," the company said. Shutting the plant "was intended to improve the company's product mix by reducing commodity production and to signicantly reduce costs,\" a Pilgrim's spokesman said in a statem:t responding to questions. Many businesses in the U.S. are struggling with excess capacity. From autos to airlines to houses, "there's a landscape of industries and sectors that are recognizing that they're going to need to scale down,ll says Nancy L. Rose, an economist at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology Department of Economics in Cambridge. Most big chicken companies have been reducing output. Earlier this year, Tyson Foods Inc. said it cut production about 5% to offset lower demand. Chicken prices have increased since Pilgrim's closed its plants. As businesses seek bankruptcy-court protection, companies and courts face tough decisions pitting creditors, shareholders, employees and communities against one another. Reorganization under bankruptcy is meant to help a company emerge with a chance at recovery and offer creditors the maximum value of what they're owed. A group of Douglas chicken farmers gathered outside an empty chicken house in Douglas, Ga. When Pilgrim's shut down production in Douglas May 15, it was "probably the biggest thing that has impacted Douglas and Coffee County" in decades, says Sidney L. Cottingham, an attorney representing the city and county in bankruptcy court. Douglas, population 11,209, is an agricultural and industrial pocket in Coffee County. Unemployment in the county hit 11.2% in April, above the national average and up from 6.5% a year ago, says the Georgia Department of Labor. The county's potential job losses linked to the plant closure could reach more than 2,000, say researchers at Georgia Southern University. Alan Carter, owner of an insurance company in Douglas, says 35% of his revenue comes from insuring chicken houses and other poultry-related operations. "When that word rst came out [of the plant closure], I panicked," he says. The Coffee Regional Medical Center is girding for a rise in uninsured patients, says controller Barry Bloom, and a loss in revenue om Pilgrim's employer-provided insurance, which came to some $2.3 million last year. Because Pilgrim's was Douglas's largest water and sewage customer, the city says it will probably have to raise water rates next year. The city says Pilgrim's owes some $280,000 in utility bills. With no plant to process the birds they raise, local chicken farmers have no income to pay off debts. Months ago, the hundreds of cavernous, metal-and-wood chicken houses in the county were worth at least $200,000 each wh: lled with chickens, farmers say. Now, except for ies and old feathers, the structures sit empty and are virtually worthless. "They just have no consideration for what they're doing to the people down here," says Walt Dockery, a fourth- generation farmer. The father of two says he derived about 90% of his income om chicken farming. _| I _I But Mr. Jackson, Pilgrim's CEO, appears to have struggled over the decision to shut the plant. In a March 11 email to Ms. Lewis, the Economic Development Authority ofcial, he said: "I do not mean to 'pluck the heart' out of Douglas or any other community. All of my 58 years have been spent in agriculture. Thirty of it in the chicken business. I grew up on a farm and my father spent his entire life farming. Not some 'rich' farmer but one just like your neighbors in Coffee County. He would be sick over this situation." Mr. Jackson declined to be interviewed. Decades ago, Douglas's economy revolved around tobacco and other crops. To lure jobs, the state in the 1950s formed the Douglas-Coffee County Industrial Authority. The first major company it landed was a meatpacker, which brought 150 jobs after Douglas offered land and agreed to buy equipment and build a chicken plant at a cost of around $300,000. Douglas residents line the road outside the airport to greet a potential buyer for the chicken plant. Pilgrim's wound up owning the facility after buying rival Gold Kist Inc. in 2006. Pilgrim's kept employment and production steady, city ofcials say. In 2007, the chicken business was booming. But chicken prices fell about 35% by the end of 2008 from the highs of 2007; poultry producers faced rising prices for feed and slackening exports. The slump hit Pilgrim's hard, partly because it had paid $1.1 billion -- much of it borrowed -- to acquire Gold Kist. Pilgrim's led for bankruptcy on Dec. 1. People in Douglas worried, but assumed they'd be spared the worst after Pilgrim's sent a Dec. 3 letter to area farmers saying, \"You will continue to be paid for your ocks during our reorganization.\" Two months later, Pilgrim's said it planned to shut three of its 32 chicken plants by the middle of May: in El Dorado, Ark.', Farmerville, La.; and Douglas. Mr. Jackson at the time said the planned closures were "apainful reection of the unprecedented challenges facing our company and our industry." Taking Wlng Cmuatln mimeln chicken mnlnd productlon' .33--l--.-.-1-r-r-.- . . . v. It. . u -- m '09 *M dala 'bouhss, lm-cs Mans 500m IJSDJ. mm 0901.0!an El Dorado says it recently gave up trying to find a buyer for the plant there aer Pilgrim's rejected a bid from a local company. Pilgrim's says it got no viable offer. In Louisiana, Gov. Bobby Jindal established an "Emergency Task Force\" and put up state funds to complete a sale to competitor Foster Farms of Livingston, Calif. The Louisiana plant was sold for about $72 million -- with half coming from the state, plus an additional $10 million from the state for equipment upgrades and other expenses in the future. In Douglas, the community rallied. Ms. Lewis asked the state for help reaching out to firms that might buy the plant. The city nailed up roadside signs saying, \"We Luv Chicken" and \"Come Home to Roost in Douglas." On March 3, chicken farmers called a meeting at the local elementary school to raise money for legal fees. Nearly 500 people packed the gym while members of a church stood outside and prayed. In three months, the group raised $30,000. Over the next few weeks, Ms. Lewis and farmers crisscrossed the state, pleading with Georgia Gov. Sonny Perdue and lawmakers to help nance a buyer. No luck so far. \"We've worked very hard to come up with something," says Bert Brantley, the governor's spokesman. The state "can only do so muc ." Pilgrim's began dismantling chicken operations in the area, slaughtering hens and selling off eggs. The steps were necessary because \"you can't close a plant and have tens of thousands of live chickens there with no place to go," Pilgrim's bankruptcy attorney, Stephen A. Youngman, said in court transcripts. Townspeople viewed the actions as a sign Pilgrim's wasn't serious about selling the plant, as it can take up to two years to restart operations once chicken production is interrupted. The city's attorney, Mr. Cottingham, led an emergency motion with the bankruptcy court to keep Pilgrim's from shutting the plant immediately. On March 19, Judge D. Michael Lynn directed Pilgrim's to slow the closing process and appointed a mediator to help complete a sale. Shortly after, he said serious bidders should have "an opportunity to sit down" with the company to see if' they could " nd a route to a bid that will work." _| Pilgrim's is under no legal obligation to sell, says Paul N. Silverstein, attorney for a group of Pilgrim's creditors. He says the group agreed with the company that selling the plant cheaply would give competitors too-easy entry into the market while stymieing efforts to cut output. That could hurt Pilgrim's chances of emerging from bankruptcy, he sa s. Cryeditors want a snong Pilgrim's to emerge, as opposed to selling off assets and getting as much as they can right now. "If the price is right, the committee would want it sold," Mr. Silverstein says. "But I don't think the committee would just support giving up a plant for next to nothing when all it's going to do is provide a potential for a competitor to bu it. " InBApril, Pilgrim's listed the Douglas plant at $80 million, according to a brochure distributed to at least one potential buyer and reviewed by The Wall Street Journal. Pilgrim's own appraisal had valued the plant at $49.5 million, according to internal company documents reviewed by the Journal. Pilgrim's conrmed that its appraisal price was "approximately $50 million." It declined to comment on why it listed the plant at $80 million. The Economic Development Authority paid for its own appraisal, which valued the plant at about $36 million. It also tried to arrange for potential buyers to tour the plant, says Ms. Lewis. One interested company was only able to take a "windshield tour" after ying to Douglas for a site visit because Pilgrim's declined to grant access, she says. I'How can you sell a plant if you can't even show it?" Pilgrim's said in court documents that it didn't want just anybody inspecting the plant. The company eventually set up a system under which certain bidders could visit after demonstrating nancial viability, among other things. South Carolina chicken company Amick, majority-owned by 081 Industries of Aurora, 111., saw an opportunity to expand. Amick offered to pay a signicant part of the $32 million for the plant and the Douglas-Coffee County Economic Development Authority agreed to chip in $2 million, according to Ms. Lewis. Pilgrim's shut the plant down on May 15. A week later, it rejected the combined Amick bid as "inadequate and not in the best interest of the debtor's estate or its constituents." Hard Hlt Unemwment rates during the urrrent recession 5am: Linn humont Amick says the rejection came as a surprise. Amick I'felt it was in active negotiations with [Pilgrim's]...and otherwise was engaged in due diligence," according to court documents. Rick Mendoza, an attorney for Amick, says, "My impression is that they did not want to sell.'I The plant closings have removed about 2% of the U.S. chicken supply, according to J.P. Morgan analyst Ken Goldman. As ofJune 24, the per-pound price for a skinless, boneless chicken breast had risen to $1.5 7, up 28% from the beginning of the year, according to the Georgia Department of Agriculture. Last month, Pilgrim's said it had repaid its $450 million ofdebtorinpossession nancing. Douglas residents still hope the plant will reopen. One recent afternoon, after a corporate jet landed at the local airport, rumors ew that a buyer might have arrived. It turned out the plane was carrying executives from Little Debbie, a maker of cookies and cakes, doing business in the region