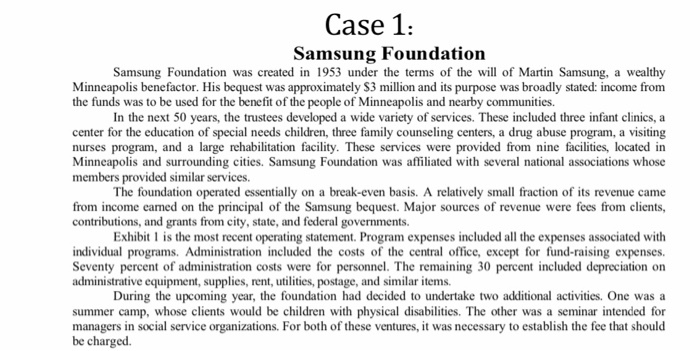

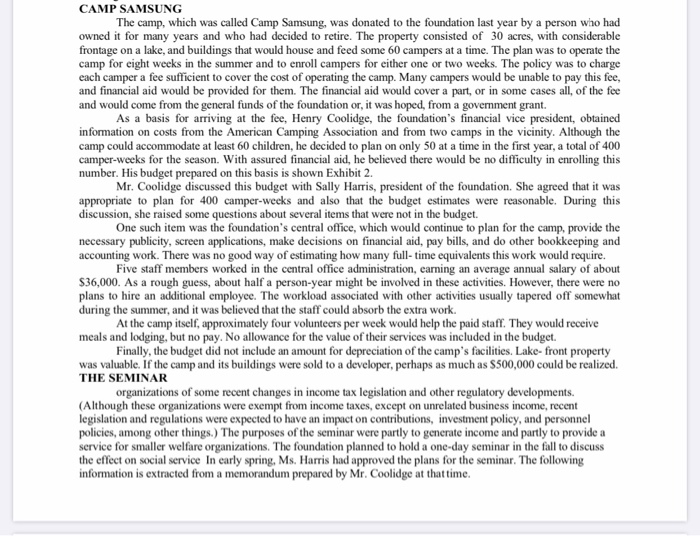

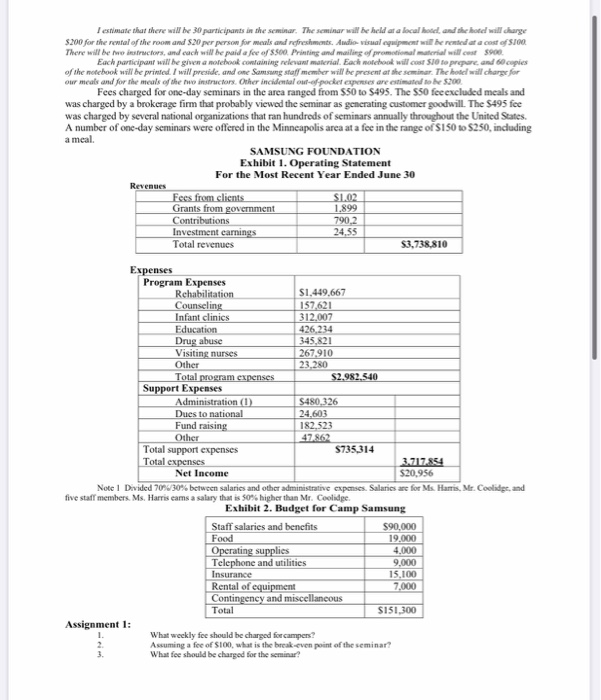

Case 1: Samsung Foundation Samsung Foundation was created in 1953 under the terms of the will of Martin Samsung, a wealthy Minneapolis benefactor. His bequest was approximately $3 million and its purpose was broadly stated income from the funds was to be used for the benefit of the people of Minneapolis and nearby communities. In the next 50 years, the trustees developed a wide variety of services. These included three infant clinics, a center for the education of special needs children, three family counseling centers, a drug abuse program, a visiting nurses program, and a large rehabilitation facility. These services were provided from nine facilities, located in Minneapolis and surrounding cities. Samsung Foundation was affiliated with several national associations whose members provided similar services. The foundation operated essentially on a break-even basis. A relatively small fraction of its revenue came from income eamed on the principal of the Samsung bequest. Major sources of revenue were fees from clients, contributions, and grants from city, state, and federal governments. Exhibit I is the most recent operating statement. Program expenses included all the expenses associated with individual programs. Administration included the costs of the central office, except for fund-raising expenses. Seventy percent of administration costs were for personnel. The remaining 30 percent included depreciation on administrative equipment, supplies, rent, utilities, postage, and similar items. During the upcoming year, the foundation had decided to undertake two additional activities. One was a summer camp, whose clients would be children with physical disabilities. The other was a seminar intended for managers in social service organizations. For both of these ventures, it was necessary to establish the fee that should be charged CAMP SAMSUNG The camp, which was called Camp Samsung, was donated to the foundation last year by a person who had owned it for many years and who had decided to retire. The property consisted of 30 acres, with considerable frontage on a lake, and buildings that would house and feed some 60 campers at a time. The plan was to operate the camp for eight weeks in the summer and to enroll campers for either one or two weeks. The policy was to charge each camper a fee sufficient to cover the cost of operating the camp. Many campers would be unable to pay this fee, and financial aid would be provided for them. The financial aid would cover a part, or in some cases all of the fee and would come from the general funds of the foundation or, it was hoped, from a government grant. As a basis for arriving at the fee, Henry Coolidge, the foundation's financial vice president, obtained information on costs from the American Camping Association and from two camps in the vicinity. Although the camp could accommodate at least 60 children, he decided to plan on only 50 at a time in the first year, a total of 400 camper-weeks for the season. With assured financial aid, he believed there would be no difficulty in enrolling this number. His budget prepared on this basis is shown Exhibit 2. Mr. Coolidge discussed this budget with Sally Harris, president of the foundation. She agreed that it was appropriate to plan for 400 camper-weeks and also that the budget estimates were reasonable. During this discussion, she raised some questions about several items that were not in the budget. One such item was the foundation's central office, which would continue to plan for the camp, provide the necessary publicity, screen applications, make decisions on financial aid, pay bills, and do other bookkeeping and accounting work. There was no good way of estimating how many full-time equivalents this work would require. Five staff members worked in the central office administration, earning an average annual salary of about $36,000. As a rough guess, about half a person-year might be involved in these activities. However, there were no plans to hire an additional employee. The workload associated with other activities usually tapered off somewhat during the summer, and it was believed that the staff could absorb the extra work. At the camp itself, approximately four volunteers per week would help the paid staff. They would receive meals and lodging, but no pay. No allowance for the value of their services was included in the budget. Finally, the budget did not include an amount for depreciation of the camp's facilities. Lake-front property was valuable. If the camp and its buildings were sold to a developer, perhaps as much as $500,000 could be realized. THE SEMINAR organizations of some recent changes in income tax legislation and other regulatory developments. (Although these organizations were exempt from income taxes, except on unrelated business income, recent legislation and regulations were expected to have an impact on contributions, investment policy, and personnel policies, among other things.) The purposes of the seminar were partly to generate income and partly to provide a service for smaller welfare organizations. The foundation planned to hold a one-day seminar in the fall to discuss the effect on social service in early spring, Ms. Harris had approved the plans for the seminar. The following information is extracted from a memorandum prepared by Mr. Coolidge at that time. I estimate that there will be 30 participants in the seminar. The seminar will be held at a local hotel and the hotd will charge $200 for the rental of the room and $20 per person for meals and refreshments Audiovisualquipment will be rented at a cost of $100 There will be two instructors, and cach will be paid a fee of $500. Printing and mailing of promotional material will cost $900. Each participant will be given a notebook containing relevant material. Each of hook will cost $10 to prepare and 60 copies of the notebook will be printed. I will preside and one Samsung staff member will be present at the seminar. The hotel will charge for our meals and for the meals of the two instructors Other incidental out-of-pocket expenses are estimated to be $200 Fees charged for one-day seminars in the area ranged from $50 to $495. The $50 fee excluded meals and was charged by a brokerage firm that probably viewed the seminar as generating customer goodwill. The 5495 fee was charged by several national organizations that ran hundreds of seminars annually throughout the United States. A number of one-day seminars were offered in the Minneapolis area at a fee in the range of S150 60 $250, including a meal SAMSUNG FOUNDATION Exhibit 1. Operating Statement For the Most Recent Year Ended June 30 Revenues Fees from clients SL.02 Grants from government 1.899 Contributions 790.2 Investment earnings 24,55 Total revenues $3,738.810 Expenses Program Expenses Rehabilitation $1,449,667 Counseling 157621 Infant clinics 312.007 Education 426,234 Drug abuse 345,821 Visiting nurses 267,910 Other 23,280 Total program expenses $2.982.540 Support Expenses Administration (1) $480.326 Dues to national 24.603 Fundraising 182.523 Other 47862 Total support expenses S735.314 Total expenses 3.717854 Net Income $20.956 Note I Divided 700/30% between salaries and other administrative expenses. Salaries are for Ms. Harris, Mt. Coolidge, and five staff members. Ms. Harris eams a salary that is 50% higher than Mr. Coolidge Exhibit 2. Budget for Camp Samsung Staff salaries and benefits $90,000 Food 19.000 Operating supplies 4,000 Telephone and utilities 9,000 Insurance 15.100 Rental of equipment 7.000 Contingency and miscellaneous Total S151,300 Assignment 1: What weekly fee should be charged for campers? Assuming a fee of S100, what is the break even point of the seminar? 3. What fee should be charged for the seminar