Answered step by step

Verified Expert Solution

Question

1 Approved Answer

CASE STUDY III-7 A Troubled Project at Modern Materials, Inc. Modern Materials, Inc. (MMI) manufactures products that are used as raw materials by large

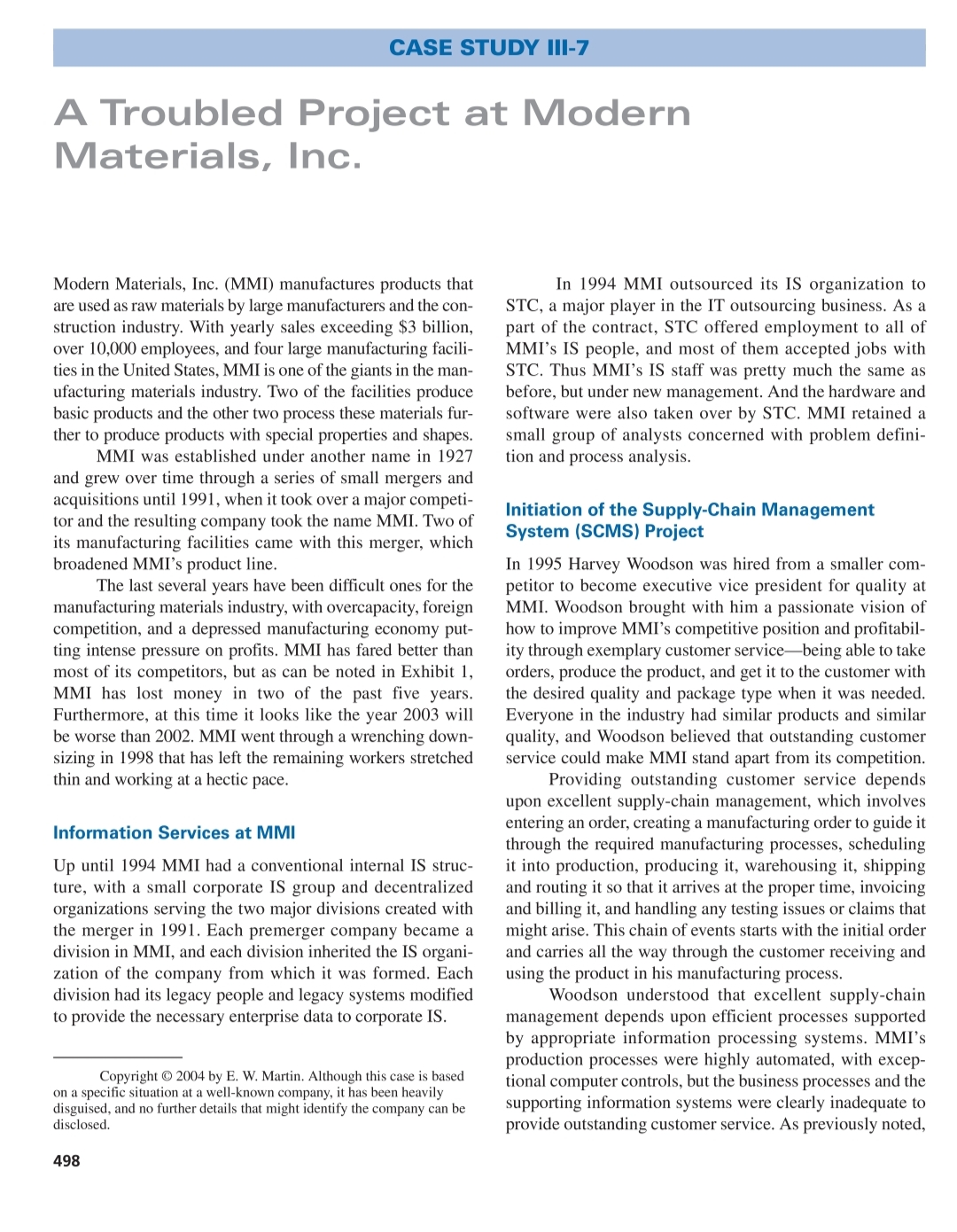

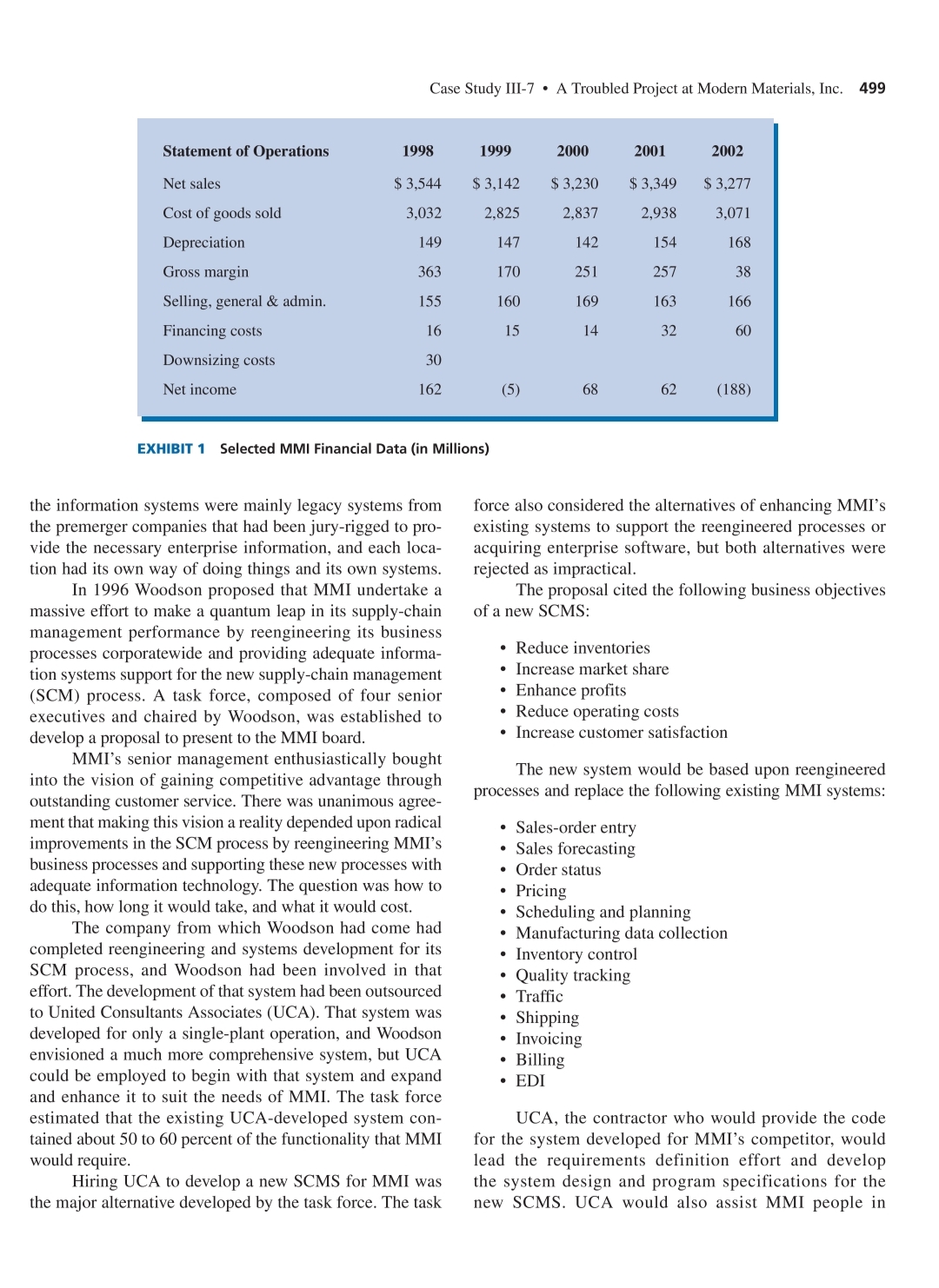

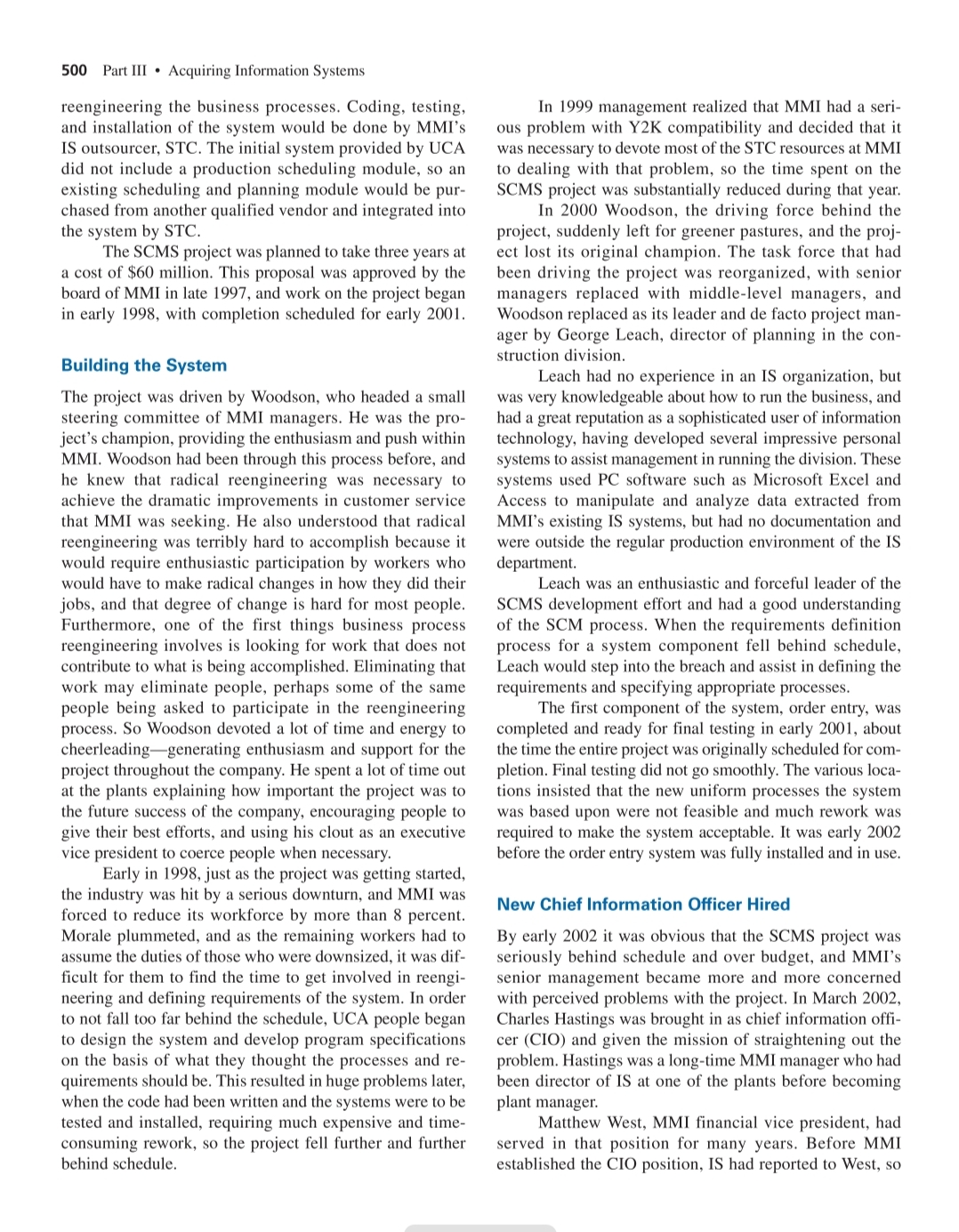

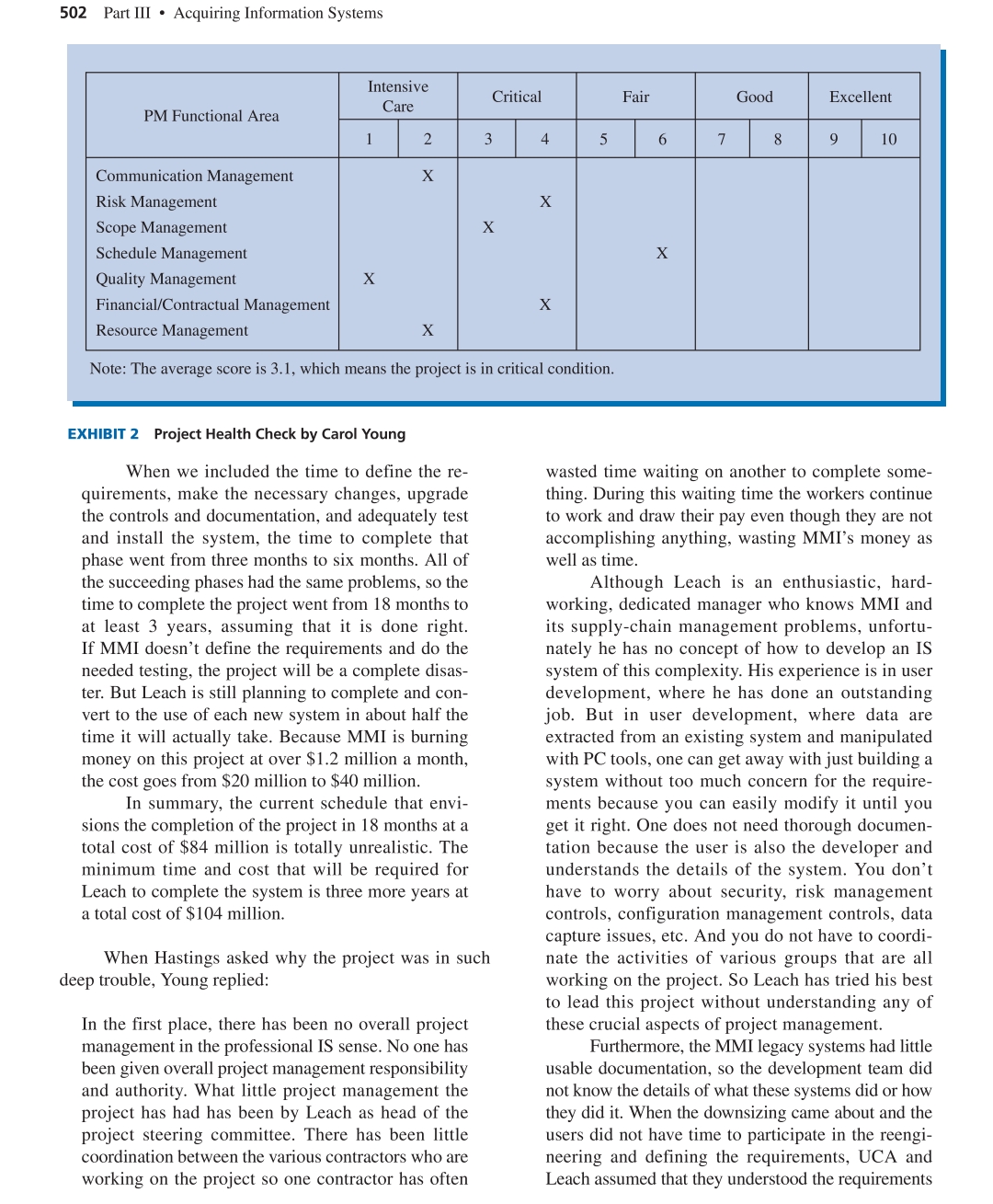

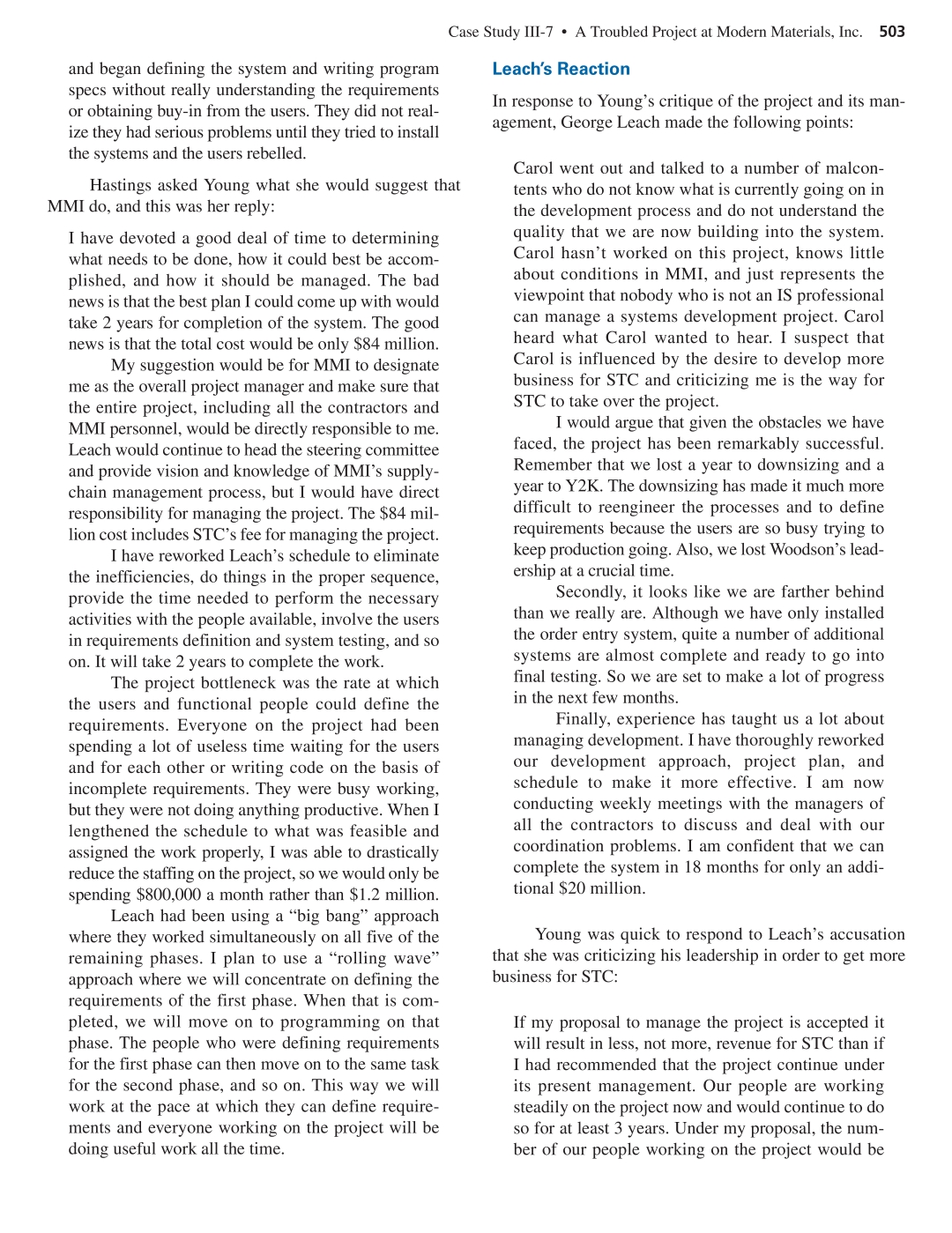

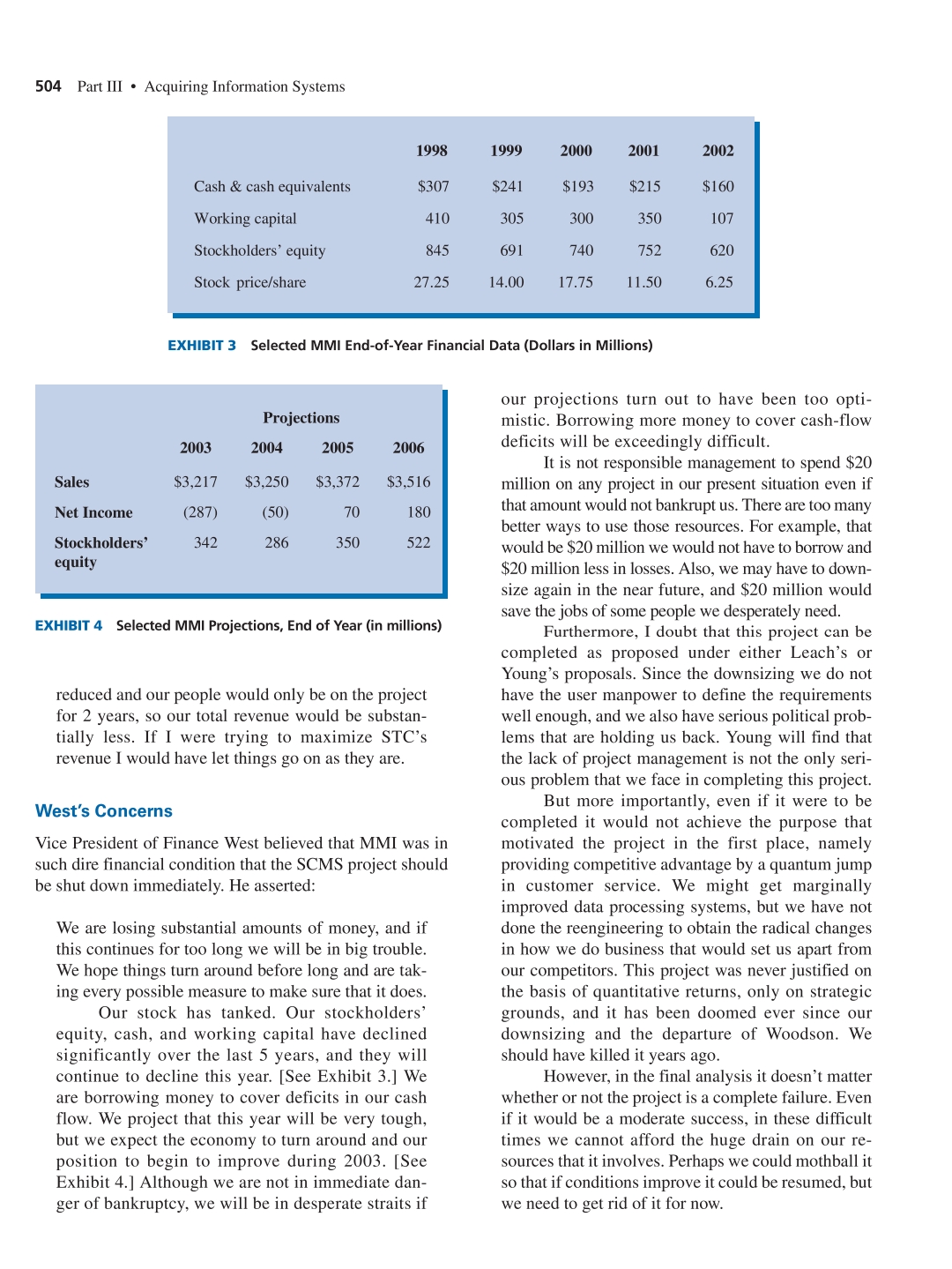

CASE STUDY III-7 A Troubled Project at Modern Materials, Inc. Modern Materials, Inc. (MMI) manufactures products that are used as raw materials by large manufacturers and the con- struction industry. With yearly sales exceeding $3 billion, over 10,000 employees, and four large manufacturing facili- ties in the United States, MMI is one of the giants in the man- ufacturing materials industry. Two of the facilities produce basic products and the other two process these materials fur- ther to produce products with special properties and shapes. MMI was established under another name in 1927 and grew over time through a series of small mergers and acquisitions until 1991, when it took over a major competi- tor and the resulting company took the name MMI. Two of its manufacturing facilities came with this merger, which broadened MMI's product line. The last several years have been difficult ones for the manufacturing materials industry, with overcapacity, foreign competition, and a depressed manufacturing economy put- ting intense pressure on profits. MMI has fared better than most of its competitors, but as can be noted in Exhibit 1, MMI has lost money in two of the past five years. Furthermore, at this time it looks like the year 2003 will be worse than 2002. MMI went through a wrenching down- sizing in 1998 that has left the remaining workers stretched thin and working at a hectic pace. Information Services at MMI Up until 1994 MMI had a conventional internal IS struc- ture, with a small corporate IS group and decentralized organizations serving the two major divisions created with the merger in 1991. Each premerger company became a division in MMI, and each division inherited the IS organi- zation of the company from which it was formed. Each division had its legacy people and legacy systems modified to provide the necessary enterprise data to corporate IS. Copyright 2004 by E. W. Martin. Although this case is based on a specific situation at a well-known company, it has been heavily disguised, and no further details that might identify the company can be disclosed. 498 In 1994 MMI outsourced its IS organization to STC, a major player in the IT outsourcing business. As a part of the contract, STC offered employment to all of MMI'S IS people, and most of them accepted jobs with STC. Thus MMI's IS staff was pretty much the same as before, but under new management. And the hardware and software were also taken over by STC. MMI retained a small group of analysts concerned with problem defini- tion and process analysis. Initiation of the Supply-Chain Management System (SCMS) Project In 1995 Harvey Woodson was hired from a smaller com- petitor to become executive vice president for quality at MMI. Woodson brought with him a passionate vision of how to improve MMI's competitive position and profitabil- ity through exemplary customer service-being able to take orders, produce the product, and get it to the customer with the desired quality and package type when it was needed. Everyone in the industry had similar products and similar quality, and Woodson believed that outstanding customer service could make MMI stand apart from its competition. Providing outstanding customer service depends upon excellent supply-chain management, which involves entering an order, creating a manufacturing order to guide it through the required manufacturing processes, scheduling it into production, producing it, warehousing it, shipping and routing it so that it arrives at the proper time, invoicing and billing it, and handling any testing issues or claims that might arise. This chain of events starts with the initial order and carries all the way through the customer receiving and using the product in his manufacturing process. Woodson understood that excellent supply-chain management depends upon efficient processes supported by appropriate information processing systems. MMI's production processes were highly automated, with excep- tional computer controls, but the business processes and the supporting information systems were clearly inadequate to provide outstanding customer service. As previously noted, Case Study III-7 A Troubled Project at Modern Materials, Inc. 499 Statement of Operations 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 Net sales $ 3,544 $ 3,142 $ 3,230 $ 3,349 $ 3,277 Cost of goods sold 3,032 2,825 2,837 2,938 3,071 Depreciation 149 147 142 154 168 Gross margin 363 170 251 257 38 Selling, general & admin. 155 160 169 163 166 Financing costs 16 15 14 32 60 Downsizing costs 30 Net income 162 (5) 68 62 (188) EXHIBIT 1 Selected MMI Financial Data (in Millions) the information systems were mainly legacy systems from the premerger companies that had been jury-rigged to pro- vide the necessary enterprise information, and each loca- tion had its own way of doing things and its own systems. In 1996 Woodson proposed that MMI undertake a massive effort to make a quantum leap in its supply-chain management performance by reengineering its business processes corporatewide and providing adequate informa- tion systems support for the new supply-chain management (SCM) process. A task force, composed of four senior executives and chaired by Woodson, was established to develop a proposal to present to the MMI board. MMI's senior management enthusiastically bought into the vision of gaining competitive advantage through outstanding customer service. There was unanimous agree- ment that making this vision a reality depended upon radical improvements in the SCM process by reengineering MMI's business processes and supporting these new processes with adequate information technology. The question was how to do this, how long it would take, and what it would cost. The company from which Woodson had come had completed reengineering and systems development for its SCM process, and Woodson had been involved in that effort. The development of that system had been outsourced to United Consultants Associates (UCA). That system was developed for only a single-plant operation, and Woodson envisioned a much more comprehensive system, but UCA could be employed to begin with that system and expand and enhance it to suit the needs of MMI. The task force estimated that the existing UCA-developed system con- tained about 50 to 60 percent of the functionality that MMI would require. Hiring UCA to develop a new SCMS for MMI was the major alternative developed by the task force. The task force also considered the alternatives of enhancing MMI's existing systems to support the reengineered processes or acquiring enterprise software, but both alternatives were rejected as impractical. The proposal cited the following business objectives of a new SCMS: Reduce inventories Increase market share Enhance profits Reduce operating costs Increase customer satisfaction The new system would be based upon reengineered processes and replace the following existing MMI systems: Sales-order entry Sales forecasting Order status Pricing Scheduling and planning Manufacturing data collection . Inventory control Quality tracking Traffic Shipping Invoicing Billing EDI UCA, the contractor who would provide the code for the system developed for MMI's competitor, would lead the requirements definition effort and develop the system design and program specifications for the new SCMS. UCA would also assist MMI people in 500 Part III Acquiring Information Systems reengineering the business processes. Coding, testing, and installation of the system would be done by MMI's IS outsourcer, STC. The initial system provided by UCA did not include a production scheduling module, so an existing scheduling and planning module would be pur- chased from another qualified vendor and integrated into the system by STC. The SCMS project was planned to take three years at a cost of $60 million. This proposal was approved by the board of MMI in late 1997, and work on the project began in early 1998, with completion scheduled for early 2001. Building the System The project was driven by Woodson, who headed a small steering committee of MMI managers. He was the pro- ject's champion, providing the enthusiasm and push within MMI. Woodson had been through this process before, and he knew that radical reengineering was necessary to achieve the dramatic improvements in customer service that MMI was seeking. He also understood that radical reengineering was terribly hard to accomplish because it would require enthusiastic participation by workers who would have to make radical changes in how they did their jobs, and that degree of change is hard for most people. Furthermore, one of the first things business process reengineering involves is looking for work that does not contribute to what is being accomplished. Eliminating that work may eliminate people, perhaps some of the same people being asked to participate in the reengineering process. So Woodson devoted a lot of time and energy to cheerleading-generating enthusiasm and support for the project throughout the company. He spent a lot of time out at the plants explaining how important the project was to the future success of the company, encouraging people to give their best efforts, and using his clout as an executive vice president to coerce people when necessary. Early in 1998, just as the project was getting started, the industry was hit by a serious downturn, and MMI was forced to reduce its workforce by more than 8 percent. Morale plummeted, and as the remaining workers had to assume the duties of those who were downsized, it was dif- ficult for them to find the time to get involved in reengi- neering and defining requirements of the system. In order to not fall too far behind the schedule, UCA people began to design the system and develop program specifications on the basis of what they thought the processes and re- quirements should be. This resulted in huge problems later, when the code had been written and the systems were to be tested and installed, requiring much expensive and time- consuming rework, so the project fell further and further behind schedule. In 1999 management realized that MMI had a seri- ous problem with Y2K compatibility and decided that it was necessary to devote most of the STC resources at MMI to dealing with that problem, so the time spent on the SCMS project was substantially reduced during that year. In 2000 Woodson, the driving force behind the project, suddenly left for greener pastures, and the proj- ect lost its original champion. The task force that had been driving the project was reorganized, with senior managers replaced with middle-level managers, and Woodson replaced as its leader and de facto project man- ager by George Leach, director of planning in the con- struction division. Leach had no experience in an IS organization, but was very knowledgeable about how to run the business, and had a great reputation as a sophisticated user of information technology, having developed several impressive personal systems to assist management in running the division. These systems used PC software such as Microsoft Excel and Access to manipulate and analyze data extracted from MMI's existing IS systems, but had no documentation and were outside the regular production environment of the IS department. Leach was an enthusiastic and forceful leader of the SCMS development effort and had a good understanding of the SCM process. When the requirements definition process for a system component fell behind schedule, Leach would step into the breach and assist in defining the requirements and specifying appropriate processes. The first component of the system, order entry, was completed and ready for final testing in early 2001, about the time the entire project was originally scheduled for com- pletion. Final testing did not go smoothly. The various loca- tions insisted that the new uniform processes the system was based upon were not feasible and much rework was required to make the system acceptable. It was early 2002 before the order entry system was fully installed and in use. New Chief Information Officer Hired By early 2002 it was obvious that the SCMS project was seriously behind schedule and over budget, and MMI's senior management became more and more concerned with perceived problems with the project. In March 2002, Charles Hastings was brought in as chief information offi- cer (CIO) and given the mission of straightening out the problem. Hastings was a long-time MMI manager who had been director of IS at one of the plants before becoming plant manager. Matthew West, MMI financial vice president, had served in that position for many years. Before MMI established the CIO position, IS had reported to West, so Case Study III-7 A Troubled Project at Modern Materials, Inc. 501 West had some familiarity with IS projects. Shortly after Hastings became CIO, West expressed concern about the project: We need to admit that the supply-chain management project is a failure, minimize our losses by killing it, and move on. I realize that it is hard to abandon a project that we have invested so much time and effort in, but times are so tough for MMI that we cannot continue to pour money down a rat hole. It took only two months for Hastings to agree that the project was in serious trouble. Although MMI senior management continued to believe in the vision of improved competitiveness through better customer service and the need for a new SCMS to support reengineered processes, the project had lost much of its drive when Woodson left MMI. Due to other serious business con- cerns, there had been no consistent personal involvement on the part of any senior manager. Consequently, there had been no top management clout to enforce the project's in- tent to make radical changes in how MMI did business. Furthermore, although people from MMI and at least three different outside contractors were working on the project, there was no overall project management responsibility. Hastings found a lot of finger-pointing with, for example, people from UCA saying "I'm waiting for MMI people to complete this," and MMI people saying "I'm waiting for STC." They were all correct because there was little over- all coordination of what they were doing. Hastings expressed concern about the project to George Leach, and Leach maintained that, although the project was well behind schedule and over budget, the un- derlying problems had been overcome and the project was now under control: We have had some serious problems to overcome- the downsizing that slowed down our requirements definition effort, the Y2K problem that diverted resources from the project, and Woodson's leadership was lost. We have also had some coordination prob- lems between the four organizations that have been working on the project. We are now well past the planned completion date of the project and $4 million over the initial budget of $60 million, which is not surprising given the problems we have had. On the other hand, we have successfully installed the order-entry system and many of the rest of the components are almost completed. We are deal- ing with the coordination problems, have recently redone the project plan, and I am confident that we can complete the system in 18 months at a total cost of $84 million. Given the importance of a supply-chain management process to MMI's future, there is no question in my mind that we should complete the project as planned. Wishing to get a more comprehensive picture of the health of the project, Hastings prevailed upon STC to bring in an experienced consultant, Carol Young, to study the sit- uation and make recommendations about how to deal with any remaining problems. Young's Findings Carol Young was an experienced project manager who was brought in from a different STC location to conduct the study at MMI. Young had just completed an STC assign- ment as the project manager of a large system development project that was completed on time and on budget. The first thing Young did was to run a quick "health check" of the project using a questionnaire that STC has used in many places. On a scale of 1 to 10, it evaluates how the project is doing in seven critical areas such as risk management, financial management, and schedule management. A score of 1 or 2 is in intensive care, 3 or 4 is critical condition, and so on. When she analyzed the results, the average score was 3.1, so the project was in deep, deep trouble (see Exhibit 2). Then Young examined the newest version of the schedule that Leach asserted would get the project com- pleted in 18 months at a cost of an additional $20 million. She reported: I took two additional people and interviewed every functional person and every end user person that had anything to do with the next phase of the schedule, which was planned to take three months. All of those people said that the project was in the toilet. The major problems were that the requirements had not been correctly identified, so they were going to have to do a lot of rework to get the requirements right, and the users were terrified because there was almost no testing in the schedule-only a little time for user acceptance testing. There was no unit testing and no integration testing. The users knew that installing the system would be a disaster. I also carefully reviewed the project plan and found that it does not take into account staffing needs. Often more work is scheduled over a time period than there are people available to do the necessary work. Thus the schedule is not feasible. Furthermore, the new systems do not have the documentation and controls necessary in a production environment. It is a mess. 502 Part III Acquiring Information Systems PM Functional Area Communication Management Risk Management Intensive Care Critical Fair Good Excellent 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Scope Management Schedule Management Quality Management X Financial/Contractual Management Resource Management X X X X X Note: The average score is 3.1, which means the project is in critical condition. X EXHIBIT 2 Project Health Check by Carol Young When we included the time to define the re- quirements, make the necessary changes, upgrade the controls and documentation, and adequately test and install the system, the time to complete that phase went from three months to six months. All of the succeeding phases had the same problems, so the time to complete the project went from 18 months to at least 3 years, assuming that it is done right. If MMI doesn't define the requirements and do the needed testing, the project will be a complete disas- ter. But Leach is still planning to complete and con- vert to the use of each new system in about half the time it will actually take. Because MMI is burning money on this project at over $1.2 million a month, the cost goes from $20 million to $40 million. In summary, the current schedule that envi- sions the completion of the project in 18 months at a total cost of $84 million is totally unrealistic. The minimum time and cost that will be required for Leach to complete the system is three more years at a total cost of $104 million. When Hastings asked why the project was in such deep trouble, Young replied: In the first place, there has been no overall project management in the professional IS sense. No one has been given overall project management responsibility and authority. What little project management the project has had has been by Leach as head of the project steering committee. There has been little coordination between the various contractors who are working on the project so one contractor has often wasted time waiting on another to complete some- thing. During this waiting time the workers continue to work and draw their pay even though they are not accomplishing anything, wasting MMI's money as well as time. Although Leach is an enthusiastic, hard- working, dedicated manager who knows MMI and its supply-chain management problems, unfortu- nately he has no concept of how to develop an IS system of this complexity. His experience is in user development, where he has done an outstanding job. But in user development, where data are extracted from an existing system and manipulated with PC tools, one can get away with just building a system without too much concern for the require- ments because you can easily modify it until you get it right. One does not need thorough documen- tation because the user is also the developer and understands the details of the system. You don't have to worry about security, risk management controls, configuration management controls, data capture issues, etc. And you do not have to coordi- nate the activities of various groups that are all working on the project. So Leach has tried his best to lead this project without understanding any of these crucial aspects of project management. Furthermore, the MMI legacy systems had little usable documentation, so the development team did not know the details of what these systems did or how they did it. When the downsizing came about and the users did not have time to participate in the reengi- neering and defining the requirements, UCA and Leach assumed that they understood the requirements and began defining the system and writing program specs without really understanding the requirements or obtaining buy-in from the users. They did not real- ize they had serious problems until they tried to install the systems and the users rebelled. Case Study III-7 A Troubled Project at Modern Materials, Inc. 503 Hastings asked Young what she would suggest that MMI do, and this was her reply: I have devoted a good deal of time to determining what needs to be done, how it could best be accom- plished, and how it should be managed. The bad news is that the best plan I could come up with would take 2 years for completion of the system. The good news is that the total cost would be only $84 million. My suggestion would be for MMI to designate me as the overall project manager and make sure that the entire project, including all the contractors and MMI personnel, would be directly responsible to me. Leach would continue head the steering committee and provide vision and knowledge of MMI's supply- chain management process, but I would have direct responsibility for managing the project. The $84 mil- lion cost includes STC's fee for managing the project. I have reworked Leach's schedule to eliminate the inefficiencies, do things in the proper sequence, provide the time needed to perform the necessary activities with the people available, involve the users in requirements definition and system testing, and so on. It will take 2 years to complete the work. The project bottleneck was the rate at which the users and functional people could define the requirements. Everyone on the project had been spending a lot of useless time waiting for the users and for each other or writing code on the basis of incomplete requirements. They were busy working, but they were not doing anything productive. When I lengthened the schedule to what was feasible and assigned the work properly, I was able to drastically reduce the staffing on the project, so we would only be spending $800,000 a month rather than $1.2 million. Leach had been using a "big bang" approach where they worked simultaneously on all five of the remaining phases. I plan to use a "rolling wave" approach where we will concentrate on defining the requirements of the first phase. When that is com- pleted, we will move on to programming on that phase. The people who were defining requirements for the first phase can then move on to the same task for the second phase, and so on. This way we will work at the pace at which they can define require- ments and everyone working on the project will be doing useful work all the time. Leach's Reaction In response to Young's critique of the project and its man- agement, George Leach made the following points: Carol went out and talked to a number of malcon- tents who do not know what is currently going on in the development process and do not understand the quality that we are now building into the system. Carol hasn't worked on this project, knows little about conditions in MMI, and just represents the viewpoint that nobody who is not an IS professional can manage a systems development project. Carol heard what Carol wanted to hear. I suspect that Carol is influenced by the desire to develop more business for STC and criticizing me is the way for STC to take over the project. I would argue that given the obstacles we have faced, the project has been remarkably successful. Remember that we lost a year to downsizing and a year to Y2K. The downsizing has made it much more difficult to reengineer the processes and to define requirements because the users are so busy trying to keep production going. Also, we lost Woodson's lead- ership at a crucial time. Secondly, it looks like we are farther behind than we really are. Although we have only installed the order entry system, quite a number of additional systems are almost complete and ready to go into final testing. So we are set to make a lot of progress in the next few months. Finally, experience has taught us a lot about managing development. I have thoroughly reworked our development approach, project plan, and schedule to make it more effective. I am now conducting weekly meetings with the managers of all the contractors to discuss and deal with our coordination problems. I am confident that we can complete the system in 18 months for only an addi- tional $20 million. Young was quick to respond to Leach's accusation that she was criticizing his leadership in order to get more business for STC: If my proposal to manage the project is accepted it will result in less, not more, revenue for STC than if I had recommended that the project continue under its present management. Our people are working steadily on the project now and would continue to do so for at least 3 years. Under my proposal, the num- ber of our people working on the project would be 504 Part III Acquiring Information Systems 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 Cash & cash equivalents $307 $241 $193 $215 $160 Working capital 410 305 300 350 107 Stockholders' equity 845 691 740 752 620 Stock price/share 27.25 14.00 17.75 11.50 6.25 EXHIBIT 3 Selected MMI End-of-Year Financial Data (Dollars in Millions) Projections 2003 2004 2005 2006 $3,217 $3,250 $3,372 $3,516 Sales Net Income Stockholders' equity (287) 342 (50) 70 180 286 350 522 EXHIBIT 4 Selected MMI Projections, End of Year (in millions) reduced and our people would only be on the project. for 2 years, so our total revenue would be substan- tially less. If I were trying to maximize STC's revenue I would have let things go on as they are. West's Concerns Vice President of Finance West believed that MMI was in such dire financial condition that the SCMS project should be shut down immediately. He asserted: We are losing substantial amounts of money, and if this continues for too long we will be in big trouble. We hope things turn around before long and are tak- ing every possible measure to make sure that it does. Our stock has tanked. Our stockholders' equity, cash, and working capital have declined significantly over the last 5 years, and they will continue to decline this year. [See Exhibit 3.] We are borrowing money to cover deficits in our cash flow. We project that this year will be very tough, but we expect the economy to turn around and our position to begin to improve during 2003. [See Exhibit 4.] Although we are not in immediate dan- ger of bankruptcy, we will be in desperate straits if our projections turn out to have been too opti- mistic. Borrowing more money to cover cash-flow deficits will be exceedingly difficult. It is not responsible management to spend $20 million on any project in our present situation even if that amount would not bankrupt us. There are too many better ways to use those resources. For example, that would be $20 million we would not have to borrow and $20 million less in losses. Also, we may have to down- size again in the near future, and $20 million would save the jobs of some people we desperately need. Furthermore, I doubt that this project can be completed as proposed under either Leach's or Young's proposals. Since the downsizing we do not have the user manpower to define the requirements well enough, and we also have serious political prob- lems that are holding us back. Young will find that the lack of project management is not the only seri- ous problem that we face in completing this project. But more importantly, even if it were to be completed it would not achieve the purpose that motivated the project in the first place, namely providing competitive advantage by a quantum jump in customer service. We might get marginally improved data processing systems, but we have not done the reengineering to obtain the radical changes in how we do business that would set us apart from our competitors. This project was never justified on the basis of quantitative returns, only on strategic grounds, and it has been doomed ever since our downsizing and the departure of Woodson. We should have killed it years ago. However, in the final analysis it doesn't matter whether or not the project is a complete failure. Even if it would be a moderate success, in these difficult times we cannot afford the huge drain on our re- sources that it involves. Perhaps we could mothball it so that if conditions improve it could be resumed, but we need to get rid of it for now. Case Study III-7 A Troubled Project at Modern Materials, Inc. 505 Leach contested West's assertion that the new system would not provide the competitive advantage originally envisioned: We have only installed one subsystem, and you can- not expect overall performance to be improved much until the entire system is installed and working. The results of this effort will be apparent when the full system is completed and installed. Our legacy systems that run production at the plants are stand-alone systems that are not integrated with other production systems or with the support systems administrative, financial, personnel, etc. The new system will integrate everything from the time the customer calls in an order through ordering the raw materials, scheduling and following through the production process, entering it into inventory, shipping it, billing it, and handling any problems with the use of the product. As a result, the customer will be able to get exactly what he wants in the shortest possible time. When the customer calls with an order, it can be entered, scheduled, and the delivery date determined while the customer is on the phone. Changes to an order can be made quickly and eas- ily. The lead time to deliver an order will be. reduced from today's 120 days to 45 days, which is just a little more than a third of what it is today! That will be a huge improvement in customer service. No one else in our industry will be able to match this. Also, this reduction in the time to deliver an order will result in tremendous savings for MMI because in- process inventory will be reduced so dramatically. And time is money for us as well as for our customers. We will be saving huge amounts of money. Furthermore, with this integrated system, man- agement information will be available in real time rather than months after the fact. We will be able to determine the profitability of each product and focus our marketing efforts on the most profitable prod- ucts, and we will be able to plan our production and load it on our facilities so as to minimize the cost of production. Not only will we be able to radically improve customer service, but we will also be able to improve the profitability of what we produce. I admit that the project has had its problems, but I am sure that we can complete it in 18 months for an additional $20 million. Although our financial condition is not good, this is a strategic project that will greatly improve our competitiveness. It repre- sents a crucial top management vision, and I can't believe that we would abandon it because of tempo- rary difficulties. MMI's future depends upon it! Mary J. Ellis, the construction division's represen- tative on the project steering committee, believed that the project should be continued and that Leach should continue to lead it. She asserted: Admittedly our financial condition is not the best, but $20 million is not going to make or break us. We must not let short-range problems cause us to lose the vision that can make such an important contribu- tion to MMI's long-term success. George has the vision, the enthusiasm, and the experience needed to complete the project. George has provided outstanding leadership, fighting through difficulty after difficulty. Without George's drive and enthusiasm the project would have failed long ago. It would be disastrous to change leadership now when the project is so close to completion.

Step by Step Solution

There are 3 Steps involved in it

Step: 1

Get Instant Access to Expert-Tailored Solutions

See step-by-step solutions with expert insights and AI powered tools for academic success

Step: 2

Step: 3

Ace Your Homework with AI

Get the answers you need in no time with our AI-driven, step-by-step assistance

Get Started