Answered step by step

Verified Expert Solution

Question

1 Approved Answer

CASE STUDY Persistence pays off... Yes, persistence pays off, but never underestimate the bucket loads of energy required for this clich to be made

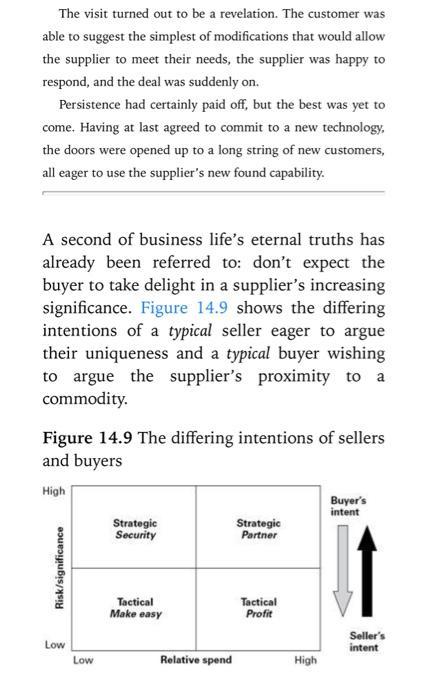

CASE STUDY Persistence pays off... Yes, persistence pays off, but never underestimate the bucket loads of energy required for this clich to be made true, par- ticularly when the obstacles to success are internal rather than external. The KA manager will need both patience and energy in equal measures, a rare combination of opposing ele- ments, and an act especially difficult to pull off with regard to one's own colleagues. I am reminded of a particularly skilled KA manager who spent the best part of 18 months winning the confidence of her customer, building a relationship across a complex net- work of individuals, and all without the reward of any signifi- cant business. Her bosses were growing impatient. Their business was the supply of technically challenging manufacturing services to the pharmaceutical industry, a group of customers known for their conservatism when weighing up potential new suppliers. For any supplier in this market, technical ability is a given, of far greater importance is their ability to demonstrate a long-term commitment to the task. But here was the problem; the supplier in this case was reluctant to make such a commitment to the opportunities unearthed by their KA manager, opportunities that would take them into new areas of manufacturing that they had hitherto thought too challenging. It was becoming clear that if they were unable to demonstrate not only a commitment but an enthusiastic commitment, then their efforts would have been in vain. At this point one might be tempted to criticise the KA manager for chasing a customer where there was no obvious match between needs and capabilities, but their ambitions in this case went beyond 'standard' KAM practice, they were in pursuit of a bigger goal, no less than the holy grail of KAM, a customer whose needs were representative of a wider group of customers, such that an enhancement of capabilities would open up a whole new stream of business well beyond that original customer. But persistence of the most dogged kind was called for, mainly because their own colleagues seemed not to understand the nature of the bigger reward inherent in this Value Machine model (see Chapter 3), arguing that the investment required could not be justified based on the returns offered by this one customer. After 18 months, appeals to technical colleagues had failed, appeals to senior management had failed and it was with a sense of resignation that the KA manager approached the customer for what felt like it would be the last time. In any other circumstance their admission that they could not supply would have been accepted, thanks would no doubt have been given for the efforts made on their behalf, and that would have been that, but now came the rewards of 18 months of relationship-building inside the customer. The cus- tomer couldn't understand the supplier's reluctance to sup- ply, and wondered if perhaps it was their own fault in having communicated their needs badly. They suggested just one more meeting, a visit to the supplier's plant, to assess for themselves what might be involved, almost as much on behalf of their Account Manager as their own requirements. The visit turned out to be a revelation. The customer was able to suggest the simplest of modifications that would allow the supplier to meet their needs, the supplier was happy to respond, and the deal was suddenly on. Persistence had certainly paid off, but the best was yet to come. Having at last agreed to commit to a new technology, the doors were opened up to a long string of new customers, all eager to use the supplier's new found capability. A second of business life's eternal truths has already been referred to: don't expect the buyer to take delight in a supplier's increasing significance. Figure 14.9 shows the differing intentions of a typical seller eager to argue their uniqueness and a typical buyer wishing to argue the supplier's proximity to a commodity. Figure 14.9 The differing intentions of sellers and buyers High Buyer's intent Strategic Security Strategic Partner Tactical Make easy Tactical Profit Risk/significance Low Low Relative spend High Seller's intent Buyers will not want too many suppliers in those upper two boxes, so demonstrations of your importance to them will need to be han- dled with care if you are not to make them nervous. Gaining the support of those in the customer that see your true value, arming them with the necessary information, and ask- ing them to brief the buyer, may be a better strategy than telling the buyers yourself. Moving north.... Much of the rest of this book is devoted to advice on how to raise your significance; mov- ing north on the supplier positioning matrix. The chapters making up Part V look at doing this from the perspective of the customer's whole business team, not just through the eyes of the buyer. The chapters making up Part VI will then suggest ways of building and communicating your value proposition in order to raise both your perceived and tangi- ble significance to the customer. Case Study - Persistence Pays Off 1. Review the case on pages 172 173 of our textbook. Based on Chapter 8. what relationship model did the Key Account manager use for this manufacturing services company? 2. Could they have employed any other relationship model to achieve the same outcome? CASE STUDY Persistence pays off... Yes, persistence pays off, but never underestimate the bucket loads of energy required for this clich to be made true, par- ticularly when the obstacles to success are internal rather than external. The KA manager will need both patience and energy in equal measures, a rare combination of opposing ele- ments, and an act especially difficult to pull off with regard to one's own colleagues. I am reminded of a particularly skilled KA manager who spent the best part of 18 months winning the confidence of her customer, building a relationship across a complex net- work of individuals, and all without the reward of any signifi- cant business. Her bosses were growing impatient. Their business was the supply of technically challenging manufacturing services to the pharmaceutical industry, a group of customers known for their conservatism when weighing up potential new suppliers. For any supplier in this market, technical ability is a given, of far greater importance is their ability to demonstrate a long-term commitment to the task. But here was the problem; the supplier in this case was reluctant to make such a commitment to the opportunities unearthed by their KA manager, opportunities that would take them into new areas of manufacturing that they had hitherto thought too challenging. It was becoming clear that if they were unable to demonstrate not only a commitment but an enthusiastic commitment, then their efforts would have been in vain. At this point one might be tempted to criticise the KA manager for chasing a customer where there was no obvious match between needs and capabilities, but their ambitions in this case went beyond 'standard' KAM practice, they were in pursuit of a bigger goal, no less than the holy grail of KAM, a customer whose needs were representative of a wider group of customers, such that an enhancement of capabilities would open up a whole new stream of business well beyond that original customer. But persistence of the most dogged kind was called for, mainly because their own colleagues seemed not to understand the nature of the bigger reward inherent in this Value Machine model (see Chapter 3), arguing that the investment required could not be justified based on the returns offered by this one customer. After 18 months, appeals to technical colleagues had failed, appeals to senior management had failed and it was with a sense of resignation that the KA manager approached the customer for what felt like it would be the last time. In any other circumstance their admission that they could not supply would have been accepted, thanks would no doubt have been given for the efforts made on their behalf, and that would have been that, but now came the rewards of 18 months of relationship-building inside the customer. The cus- tomer couldn't understand the supplier's reluctance to sup- ply, and wondered if perhaps it was their own fault in having communicated their needs badly. They suggested just one more meeting, a visit to the supplier's plant, to assess for themselves what might be involved, almost as much on behalf of their Account Manager as their own requirements. The visit turned out to be a revelation. The customer was able to suggest the simplest of modifications that would allow the supplier to meet their needs, the supplier was happy to respond, and the deal was suddenly on. Persistence had certainly paid off, but the best was yet to come. Having at last agreed to commit to a new technology, the doors were opened up to a long string of new customers, all eager to use the supplier's new found capability. A second of business life's eternal truths has already been referred to: don't expect the buyer to take delight in a supplier's increasing significance. Figure 14.9 shows the differing intentions of a typical seller eager to argue their uniqueness and a typical buyer wishing to argue the supplier's proximity to a commodity. Figure 14.9 The differing intentions of sellers and buyers High Buyer's intent Strategic Security Strategic Partner Tactical Make easy Tactical Profit Risk/significance Low Low Relative spend High Seller's intent Buyers will not want too many suppliers in those upper two boxes, so demonstrations of your importance to them will need to be han- dled with care if you are not to make them nervous. Gaining the support of those in the customer that see your true value, arming them with the necessary information, and ask- ing them to brief the buyer, may be a better strategy than telling the buyers yourself. Moving north.... Much of the rest of this book is devoted to advice on how to raise your significance; mov- ing north on the supplier positioning matrix. The chapters making up Part V look at doing this from the perspective of the customer's whole business team, not just through the eyes of the buyer. The chapters making up Part VI will then suggest ways of building and communicating your value proposition in order to raise both your perceived and tangi- ble significance to the customer. Case Study - Persistence Pays Off 1. Review the case on pages 172 173 of our textbook. Based on Chapter 8. what relationship model did the Key Account manager use for this manufacturing services company? 2. Could they have employed any other relationship model to achieve the same outcome? CASE STUDY Persistence pays off... Yes, persistence pays off, but never underestimate the bucket loads of energy required for this clich to be made true, par- ticularly when the obstacles to success are internal rather than external. The KA manager will need both patience and energy in equal measures, a rare combination of opposing ele- ments, and an act especially difficult to pull off with regard to one's own colleagues. I am reminded of a particularly skilled KA manager who spent the best part of 18 months winning the confidence of her customer, building a relationship across a complex net- work of individuals, and all without the reward of any signifi- cant business. Her bosses were growing impatient. Their business was the supply of technically challenging manufacturing services to the pharmaceutical industry, a group of customers known for their conservatism when weighing up potential new suppliers. For any supplier in this market, technical ability is a given, of far greater importance is their ability to demonstrate a long-term commitment to the task. But here was the problem; the supplier in this case was reluctant to make such a commitment to the opportunities unearthed by their KA manager, opportunities that would take them into new areas of manufacturing that they had hitherto thought too challenging. It was becoming clear that if they were unable to demonstrate not only a commitment but an enthusiastic commitment, then their efforts would have been in vain. At this point one might be tempted to criticise the KA manager for chasing a customer where there was no obvious match between needs and capabilities, but their ambitions in this case went beyond 'standard' KAM practice, they were in pursuit of a bigger goal, no less than the holy grail of KAM, a customer whose needs were representative of a wider group of customers, such that an enhancement of capabilities would open up a whole new stream of business well beyond that original customer. But persistence of the most dogged kind was called for, mainly because their own colleagues seemed not to understand the nature of the bigger reward inherent in this Value Machine model (see Chapter 3), arguing that the investment required could not be justified based on the returns offered by this one customer. After 18 months, appeals to technical colleagues had failed, appeals to senior management had failed and it was with a sense of resignation that the KA manager approached the customer for what felt like it would be the last time. In any other circumstance their admission that they could not supply would have been accepted, thanks would no doubt have been given for the efforts made on their behalf, and that would have been that, but now came the rewards of 18 months of relationship-building inside the customer. The cus- tomer couldn't understand the supplier's reluctance to sup- ply, and wondered if perhaps it was their own fault in having communicated their needs badly. They suggested just one more meeting, a visit to the supplier's plant, to assess for themselves what might be involved, almost as much on behalf of their Account Manager as their own requirements. The visit turned out to be a revelation. The customer was able to suggest the simplest of modifications that would allow the supplier to meet their needs, the supplier was happy to respond, and the deal was suddenly on. Persistence had certainly paid off, but the best was yet to come. Having at last agreed to commit to a new technology, the doors were opened up to a long string of new customers, all eager to use the supplier's new found capability. A second of business life's eternal truths has already been referred to: don't expect the buyer to take delight in a supplier's increasing significance. Figure 14.9 shows the differing intentions of a typical seller eager to argue their uniqueness and a typical buyer wishing to argue the supplier's proximity to a commodity. Figure 14.9 The differing intentions of sellers and buyers High Buyer's intent Strategic Security Strategic Partner Tactical Make easy Tactical Profit Risk/significance Low Low Relative spend High Seller's intent Buyers will not want too many suppliers in those upper two boxes, so demonstrations of your importance to them will need to be han- dled with care if you are not to make them nervous. Gaining the support of those in the customer that see your true value, arming them with the necessary information, and ask- ing them to brief the buyer, may be a better strategy than telling the buyers yourself. Moving north.... Much of the rest of this book is devoted to advice on how to raise your significance; mov- ing north on the supplier positioning matrix. The chapters making up Part V look at doing this from the perspective of the customer's whole business team, not just through the eyes of the buyer. The chapters making up Part VI will then suggest ways of building and communicating your value proposition in order to raise both your perceived and tangi- ble significance to the customer. Case Study - Persistence Pays Off 1. Review the case on pages 172 173 of our textbook. Based on Chapter 8. what relationship model did the Key Account manager use for this manufacturing services company? 2. Could they have employed any other relationship model to achieve the same outcome? CASE STUDY Persistence pays off... Yes, persistence pays off, but never underestimate the bucket loads of energy required for this clich to be made true, par- ticularly when the obstacles to success are internal rather than external. The KA manager will need both patience and energy in equal measures, a rare combination of opposing ele- ments, and an act especially difficult to pull off with regard to one's own colleagues. I am reminded of a particularly skilled KA manager who spent the best part of 18 months winning the confidence of her customer, building a relationship across a complex net- work of individuals, and all without the reward of any signifi- cant business. Her bosses were growing impatient. Their business was the supply of technically challenging manufacturing services to the pharmaceutical industry, a group of customers known for their conservatism when weighing up potential new suppliers. For any supplier in this market, technical ability is a given, of far greater importance is their ability to demonstrate a long-term commitment to the task. But here was the problem; the supplier in this case was reluctant to make such a commitment to the opportunities unearthed by their KA manager, opportunities that would take them into new areas of manufacturing that they had hitherto thought too challenging. It was becoming clear that if they were unable to demonstrate not only a commitment but an enthusiastic commitment, then their efforts would have been in vain. At this point one might be tempted to criticise the KA manager for chasing a customer where there was no obvious match between needs and capabilities, but their ambitions in this case went beyond 'standard' KAM practice, they were in pursuit of a bigger goal, no less than the holy grail of KAM, a customer whose needs were representative of a wider group of customers, such that an enhancement of capabilities would open up a whole new stream of business well beyond that original customer. But persistence of the most dogged kind was called for, mainly because their own colleagues seemed not to understand the nature of the bigger reward inherent in this Value Machine model (see Chapter 3), arguing that the investment required could not be justified based on the returns offered by this one customer. After 18 months, appeals to technical colleagues had failed, appeals to senior management had failed and it was with a sense of resignation that the KA manager approached the customer for what felt like it would be the last time. In any other circumstance their admission that they could not supply would have been accepted, thanks would no doubt have been given for the efforts made on their behalf, and that would have been that, but now came the rewards of 18 months of relationship-building inside the customer. The cus- tomer couldn't understand the supplier's reluctance to sup- ply, and wondered if perhaps it was their own fault in having communicated their needs badly. They suggested just one more meeting, a visit to the supplier's plant, to assess for themselves what might be involved, almost as much on behalf of their Account Manager as their own requirements. The visit turned out to be a revelation. The customer was able to suggest the simplest of modifications that would allow the supplier to meet their needs, the supplier was happy to respond, and the deal was suddenly on. Persistence had certainly paid off, but the best was yet to come. Having at last agreed to commit to a new technology, the doors were opened up to a long string of new customers, all eager to use the supplier's new found capability. A second of business life's eternal truths has already been referred to: don't expect the buyer to take delight in a supplier's increasing significance. Figure 14.9 shows the differing intentions of a typical seller eager to argue their uniqueness and a typical buyer wishing to argue the supplier's proximity to a commodity. Figure 14.9 The differing intentions of sellers and buyers High Buyer's intent Strategic Security Strategic Partner Tactical Make easy Tactical Profit Risk/significance Low Low Relative spend High Seller's intent Buyers will not want too many suppliers in those upper two boxes, so demonstrations of your importance to them will need to be han- dled with care if you are not to make them nervous. Gaining the support of those in the customer that see your true value, arming them with the necessary information, and ask- ing them to brief the buyer, may be a better strategy than telling the buyers yourself. Moving north.... Much of the rest of this book is devoted to advice on how to raise your significance; mov- ing north on the supplier positioning matrix. The chapters making up Part V look at doing this from the perspective of the customer's whole business team, not just through the eyes of the buyer. The chapters making up Part VI will then suggest ways of building and communicating your value proposition in order to raise both your perceived and tangi- ble significance to the customer. Case Study - Persistence Pays Off 1. Review the case on pages 172 173 of our textbook. Based on Chapter 8. what relationship model did the Key Account manager use for this manufacturing services company? 2. Could they have employed any other relationship model to achieve the same outcome?

Step by Step Solution

★★★★★

3.44 Rating (157 Votes )

There are 3 Steps involved in it

Step: 1

Case Study Persistence Pays Off 1 Review the case on pages 172 173 of our textbook Based on Chapter ...

Get Instant Access to Expert-Tailored Solutions

See step-by-step solutions with expert insights and AI powered tools for academic success

Step: 2

Step: 3

Ace Your Homework with AI

Get the answers you need in no time with our AI-driven, step-by-step assistance

Get Started