Answered step by step

Verified Expert Solution

Question

1 Approved Answer

CASE STUDY Struggle For Development-a story of change and conflict By Nuzhat Lotia, University of Melbourne Struggle For Development (SFD) is a community development

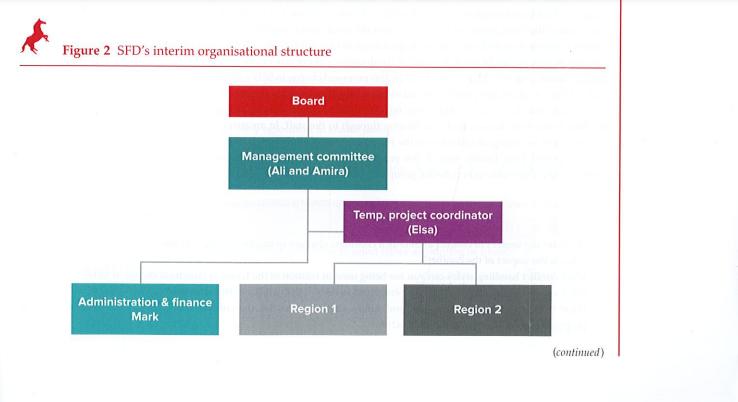

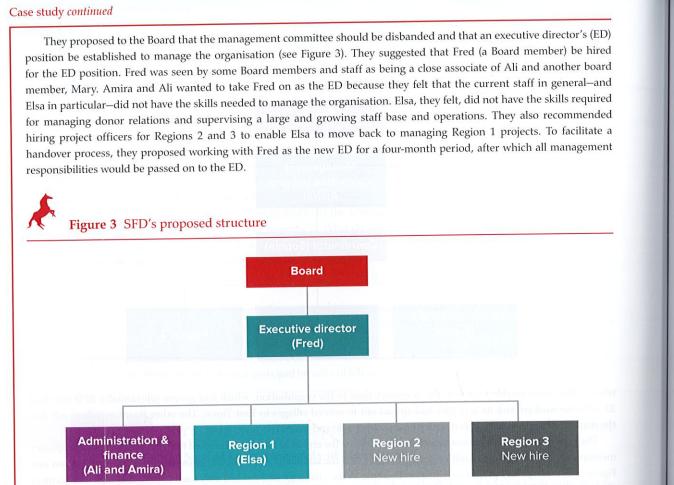

CASE STUDY Struggle For Development-a story of change and conflict By Nuzhat Lotia, University of Melbourne Struggle For Development (SFD) is a community development organisation based in Sydney. It was set up in early 2014 by a group of students who were studying International Development. The students-Bryan, Elsa (originally from East Timor), Ali, Shanti, Sophia and Amira-had been involved in a project in East Timor as part of their development practice. The project, a modest literacy and education program for women in the village that Elsa was originally from, had been extremely successful, and they had returned to Australia determined to continue the work that they had started. SFD was established by a group of 11 people-the original six from the development practice project and five of their university friends. Its founding vision was one of empowering marginalised communities including the economically disadvantaged, women and children. The organisation implements projects focusing on education and skills development for women and works towards their greater participation in decision-making in all spheres of their lives, both in East Timor and Australia. Only one of the founders, Sophia, worked full-time for SFD (as its coordinator), while the others worked full-time elsewhere. Together they formed the Board of SFD. The coordinator's role involved managing the day-to-day operations and decision-making. Most Board members visited SFD's office in the evenings to discuss issues and work on funding applications, reports and administrative tasks. They were all closely involved in running the organisation and managing its various projects. SFD's operations grew, and in late 2015 the Board set up a management committee (a sub-committee of the Board). Comprising of the three most experienced Board members (Shanti, Ali and Amira), the management committee's function was to work closely with the coordinator. The Board was happy to hand over its overseeing role to the management committee because of SFD's growing size and operations. The management committee made most decisions and worked closely with Sophia, who would often seek advice from one or all of its members on operational issues. By 2016, SFD had employed two more of the founders in full-time positions: Elsa became a project officer and Mark became administration and finance coordinator. Some Board members were unhappy with this as they felt that the management committee had not fully explored all recruitment options. Some of them raised this issue but, after some heated arguments, decided to let it go as they did not want to offend their friends. At this point, Shanti decided to resign from both the management committee and the Board. She felt she was being targeted because Mark was a close friend of hers. The management committee was reduced to just two members, Ali and Amira (see Figure 1), which became an Figure 1 SFD's organisational structure Administration & finance Mark Board Management committee (Ali and Amira) Coordinator (Sophia) Project officer Region 1 Elsa Region 2 issue as they were unable to devote the necessary time to the organisation, which had grown substantially. SFD now had 23 full-time workers and its activities had spread out to several villages in East Timor. The other Board members felt that the management committee was not playing its proper role and raised this as an issue. The management issue was exacerbated when, towards the end of 2016, Sophia resigned from her position. As a temporary measure, the management committee decided to give Elsa the additional responsibility of overseeing work in all regions (see Figure 2) as a temporary project coordinator. Elsa rose to the challenge and worked very hard to fulfil this new management responsibility, doing quite a good job (with Ali and Amira's support). To fill the void created by Sophia's resignation and the reduced size of the management committee, Ali and Amira initiated discussions around bringing about some structural changes in the organisation, especially as SFD had just been funded to do some work in a new region (Region 3). Figure 2 SFD's interim organisational structure Administration & finance Mark Board Management committee (Ali and Amira) Region 1 Temp. project coordinator (Elsa) Region 2 (continued) Case study continued They proposed to the Board that the management committee should be disbanded and that an executive director's (ED) position be established to manage the organisation (see Figure 3). They suggested that Fred (a Board member) be hired for the ED position. Fred was seen by some Board members and staff as being a close associate of Ali and another board member, Mary. Amira and Ali wanted to take Fred on as the ED because they felt that the current staff in general-and Elsa in particular-did not have the skills needed to manage the organisation. Elsa, they felt, did not have the skills required for managing donor relations and supervising a large and growing staff base and operations. They also recommended hiring project officers for Regions 2 and 3 to enable Elsa to move back to managing Region 1 projects. To facilitate a handover process, they proposed working with Fred as the new ED for a four-month period, after which all management responsibilities would be passed on to the ED. Figure 3 SFD's proposed structure Administration & finance (Ali and Amira) Board Executive director (Fred) Region 1 (Elsa) Region 2 New hire Region 3 New hire Ali and Amira presented their proposal in a Board meeting in March 2017, the first time that Elsa and the majority of members of the Board heard about it. (Two members of the Board had heard about it through informal discussions with Amira. These two, who were regarded as allies of Ali and Amira, supported the proposal, along with the putative ED, Fred.) However, four Board members were not happy with the proposal and felt that the ED position should be offered to Elsa. They argued that bringing in another person over her head would undermine her authority and reputation. (These were the members who had worked with Elsa in the past and had close affiliations with each other.) Initially, they did not convey their opposition directly, but blocked and stalled the decision-making process by getting into long discussions on the proposed organisational structure. Meanwhile, Elsa saw this proposed change in SFD's structure as a demotion in terms of her position and in terms of reporting to another Board member. She threatened to resign if the new structure was implemented. Two factions had been created in the Board-pro-Elsa and pro-Fred. Consequently, there was a lot of tension among the Board members, tension that was filtering through to the staff. In an attempt to reconcile the differences, Amira and Ali suggested recruiting an outsider for the ED position instead of Fred; but this was unacceptable to the Board members who supported Elsa. Finally, two of the pro-Elsa faction stopped participating in Board meetings. The interpersonal relationships of this once very cohesive group had become extremely strained. This case is based on actual events, but names and characteristics have been changed to maintain anonymity Discussion questions What are the sources of conflict at SFD as it considers changes in organisational structure? 1 2 What is the impact of the conflict? 3 What conflict handling styles can you see being used in relation to the issues of structural change at SFD? 4 What conflict handling style should be employed to resolve the conflict in this situation? 5 What structural approaches can Ali and Amira employ to resolve the conflict and minimise the resistance to the proposed change in organisational structure? The cascading effect of unethical leadership By Joseph Crawford and Toby Newstead, University of Tasmania CASE STUDY Trade Training is one of the 10 largest registered training organisations in Australia and is the primary provider of vocational education and training in its state. Offering more than 330 qualifications and courses ranging from pre-vocational programs to apprenticeships and advanced diplomas, TradeTraining has approximately 26 000 students, 12 campuses and over 1000 employees. As a state-owned enterprise, Trade Training plays a vital role in its local economy. Trade Training operates under a traditional hierarchical structure. Its board of directors oversees a chief executive officer (CEO) who leads a senior management team which is responsible for a number of different divisions including corporate services, education, education support and people and culture. The CEO's strategic focus is on enabling Trade Training's 1000 staff to offer quality training opportunities to students, and to provide employment-ready graduates to domestic businesses. The CEO is in a clear leadership position, with the power to allocate rewards and resources, and to greatly influence the general work environment. In 2017, Trade Training's annual report stated: 'All staff members, regardless of whether they are teachers, corporate or support staff, believe in the One Trade Training/One Team philosophy, and are focused upon the student or customer. However, a report issued by the state's Integrity Commission in May 2017 made public the fact that the leadership practices of Trade Training's senior managers were in stark contrast to this philosophy. The Integrity Commission's mandate is to ensure trust in government, and one of its key objectives is to enhance ethical conduct within government and its enterprises (such as Trade Training). Following a complaint made in February 2016, the Commission launched a comprehensive investigation into two senior executive officers of Trade Training. The Commission uncovered evidence that then-CEO John and his second-in-command, Kathy, were far more concerned with their own reward and remuneration than with the best interests of the organisation, its students and its employees. The report evidenced unethical leadership practices stemming from the nepotism and favouritism that John showed to Kathy-and that Kathy in turn showed to her subordinates. During his tenure as CEO of Trade Training, John was also chair of the board of the peak industry body Training Australia, where Kathy was then CEO. It was while they were working together at Training Australia that Kathy let John know she was looking for a new job. John then used the power and influence of his CEO role at Trade Training to provide Kathy with confidential details on upcoming employment opportunities, including forthcoming organisational restructures and the hiring committee's unpublished selection criteria. John also served as Kathy's referee when she eventually applied for a divisional manager role at TradeTraining. Kathy was offered the job at Trade Training, but she declined. Following that, John intervened, using his influence and power to incentivise the interstate move that Kathy would have to make if she reconsidered her decision. John personally customised a remuneration package that included bumping up the base salary by $12 000. In light of these incentives, Kathy accepted the role. The state government policies under which TradeTraining falls has clear policies for declaring conflicts of interest (such as when the CEO of an organisation intervenes in the recruitment process of one of his friends). But no declaration of John and Kathy's relationship was made. After commencing her role at Trade Training, Kathy benefited from a number of promotions and extremely generous working arrangements, all of which came at the behest of John, without due process. Within the first 12 months, Kathy's salary was increased by 45% (the equivalent of a $55 000 per annum raise). John also provided her with an incentive payment scheme consisting of $30 000 in benefits, including an unprecedented $6000 bonus on each anniversary of her appointment. The cascading effect of John's nepotism, favouritism and unethical leadership was evidenced by Kathy adopting similar unethical practices. Shortly after her appointment, Kathy chose not to tender an $18 000 consulting contract, instead awarding the job to her friend, Michael. Michael was a referee on Kathy's initial application to Trade Training and another colleague from Training Australia. In order to fulfil auditing requirements, John tried to cover up this breach of process by requesting a retrospective proposal from Michael. However, metadata on the proposal proved it was created after the contract had commenced. Furthermore, Kathy, like John, provided confidential information relating to upcoming jobs within Trade Training to her friends and former colleagues at Training Australia. She also regularly misused her government credit card for personal purchases, including paying for flights to a job interview with another organisation. Media coverage of the Integrity Commission's report garnered extensive public interest: it was the funds of a public service that were being misused in these instances of unethical recruitment, reimbursement, incentivising and tendering. (continued) Case study continued John's unethical leadership clearly cascaded to Kathy, and the combined effect of their unethical practices had a profound and negative impact on Trade Training's ethical climate and organisational culture. Following the Integrity Commission's report, both John and Kathy resigned, and a new CEO from interstate was appointed. This case is based on actual events, but names and some characteristics have been changed to maintain anonymity Discussion questions 1 Use the view of shared leadership to explain the unethical practices of John and Kathy. 2 Using the elements of LMX theory as a guide, what ramifications would John's actions have had on his other employees and on the organisation as a whole? 3 Considering the two follower-centric leadership theories, to what degree were the followers and subordinates responsible for John and Kathy's unethical leadership? 4 Which of the eight competencies associated with effective leadership was most lacking in John's unethical leadership practices? 5 In appointing a new CEO, would Trade Training prefer an authentic or ethical leader? Why?

Step by Step Solution

★★★★★

3.39 Rating (152 Votes )

There are 3 Steps involved in it

Step: 1

1 The sources of conflict at SFD as it considers changes in organizational structure are rooted in a lack of communication between upper management and staff The first source of conflict is a lack of ...

Get Instant Access to Expert-Tailored Solutions

See step-by-step solutions with expert insights and AI powered tools for academic success

Step: 2

Step: 3

Ace Your Homework with AI

Get the answers you need in no time with our AI-driven, step-by-step assistance

Get Started