Case: The NFL, NCAA, and Concussions: The Unethical Exploitation of Athletes IRON MIKE WEBSTER Iron Mike Webster didn't play football in high school until his

Case: The NFL, NCAA, and Concussions: The Unethical Exploitation of Athletes

"IRON MIKE" WEBSTER

"Iron Mike" Webster didn't play football in high school until his junior year, but nevertheless he stood out enough to win a scholarship to the University of Wisconsin. After college, he tried out for the National Football League (NFL) and was drafted in the fifth round by the Pittsburgh Steelers.5 Webster played on four Super Bowl championship teams, becoming a legend and a heroic figure in Pittsburgh over his 17-year pro football career. He died 11 years after retirement, setting the stage for the NFL to recognize that brain damage could result from football.

Dr. Bennet Omalu, the neuropathologist who performed Webster's autopsy, described Webster's body as looking much older than his age?beat up, worn out, drained?as if he were 70 instead of 50. Webster had painful cracks the length of his feet, varicose veins, several herniated discs, a broken vertebra, torn rotator cuff and separated shoulder, and an enlarged heart. Before he died, he had been losing his teeth

Webster often hit the opposing football player with his head. According to Robert Stern, a neuropsychologist at Boston University, In football, one has to expect that almost every play of every game and every practice, they're going to be hitting their heads against each other. That's the nature of the game. Those things seem to happen around 1,000 to 1,500 times a year. Each time that happens, it's around 20G or more. That's the equivalent of driving a car at 35 miles per hour into a brick wall 1,000 to 1,500 times per year.7

After Webster left football, his wife said he became angry, lacked patience, and did not have enough physical stamina for normal activities. Family members described him as increasingly confused. He and his wife eventually divorced. They were broke, their home was under foreclosure, and their pride was gone. Webster forged prescriptions for Ritalin that he used to enhance cognitive functioning. He would ask a friend to shock him with a Taser so he could sleep. Webster stopped conducting TV interviews because he could not focus. His son Colin said, "Maybe the saddest thing I ever heard him say was when someone saw my dad and said, 'Aren't you Mike Webster?' And he said, 'I used to be.'"8 With the help of an attorney, Webster filed a disability claim. The NFL's retirement board had a disability committee whose head was the commissioner himself, and Webster was granted disability payments. The NFL stated that his disability is the result of head injuries he suffered as a football player."9 Then, in 2002, at age 50, Webster died of a heart attack.

BRAIN INJURY AND CTE

After Webster's death, he was diagnosed with chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE). Boston University's Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy Center defines CTE as

A progressive degenerative disease of the brain found in athletes (and others) with a history of repetitive brain trauma, including symptomatic concussions as well as asymptomatic subconcussive hits to the head. . . . These changes in the brain can begin months, years, or even decades after the last brain trauma or end of active athletic involvement. The brain degeneration is associated with memory loss, confusion, impaired judgment, impulse control problems, aggression, depression, and, eventually, progressive dementia

Boston University is a leader in studying CTE. In 2015, Boston University analyzed the brains of 91 deceased NFL players and confirmed CTE in 87 of them. The sample was skewed in that the estates of the deceased players had to be willing to submit the brains of the former players for autopsy, and many did so because the player had manifested symptoms before dying. The total incidence of CTE found by the lab in all former players (including those who participated at the high school, college, semi-pro, and professional levels) was 131 out of 165. Forty percent had played as linemen. Researchers believe that it might be repeated minor head trauma that poses the greatest risk of CTE, not just concussions.12 In 2013, the NFL settled with its players' union to pay medical and other benefits to players who suffered concussions and related injuries. Some NFL players had opted out of the settlement, which allowed them to sue the NFL separately. The 2013 players' disability settlement was contested by players who, because of constraints such as lack of a specific disease diagnosis, were excluded from participation and payment. These players eventually filed suit, which they appealed up to the U.S. Supreme Court.13 In the lawsuit, lawyers representing 135 former NFL players provided the following health examples:

? Tony Gaiter, aged 42?could not drive or hold a job, suffered from severe depression, and had a history of homelessness.

? Tracy Scroggins, aged 47?suffered from depression, insomnia, anxiety, and poor impulse control, and could not hold a job or support himself.

? William Floyd, aged 44?had chronic headaches and was incapable of working.

In 2016, the U.S. Supreme Court decided not to hear the appeal, thus the original 2013 settlement was upheld. Payments to the 20,000 former players covered under the agreement could reach $1 billion over 65 years. The NFL estimated that around one third of former players could suffer from Alzheimer's disease or moderate dementia. The maximum payout varies by classification of the injury or disease:

? Level 1.5 neurocognitive impairment: $1.5 million

? Level 2 neurocognitive impairment: $3 million

? Parkinson's disease: $3.5 million

? Alzheimer's disease: $3.5 million

? Death with CTE: $4 million

? ALS (Lou Gehrig's disease): $5 million

Sometimes, in the heat of competition, players and team medical staff might overlook head injuries and fail to follow the concussion protocol to determine if a player had suffered a concussion. However, in 2016 the NFL made the concussion protocol mandatory and threatened teams with stiff fines for failing to follow it.15 Representatives of both the NFL and the players' union are assigned to monitor the procedures during games. Fines can reach $150,000 and the forfeiture of one or more future draft picks. Through observation and rules, such as prohibiting helmet-to-helmet hits, the NFL has been attempting to reduce the number of concussions and to mitigate their impact.16 According to data released by the NFL, the incidence of concussions since 2012 are:

? 2012?261

? 2013?229

? 2014?206

? 2015?275

? 2016?244

Concussions declined by more than 10 percent for each of the first 2 years measured, but then increased by 32 percent in 2015, reaching a new high of 275 and then declining to 244. As noted previously, measuring the number of repeated minor trauma, rather than for concussions, would have meant even worse head injury results for football players.

NFL COVER-UP?

Did the NFL attempt to cover up the link between concussions and debilitating effects such as Alzheimer's disease, dementia, and depression? Or did the NFL just have another point of view? It recognized Mike Webster's disability in 2000 and agreed to a disability settlement with the players' union. Yet it was slow in transitioning from acceptance of injury as an occupational hazard in a brutal sport like football to acknowledging that playing football could lead to brain damage.

General awareness of an association between playing football and concussions has been present in the medical community since the 1930s, and later in the sports-medicine specialty. The National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) medical handbook of 1933 warned that concussions were treated too lightly, and in 1937 the American Football Coaches Association urged that players who had suffered a concussion be removed from the game.18 In 1952, the New England Journal of Medicine concluded that players who had suffered three concussions should not play football again. In 1973, the second impact syndrome was identified, which refers to a player suffering a concussion while still recovering from a previous one. In 1991, a formal grading system for concussion severity and allowing players to return to play was applied by the NCAA and many high schools. But it took until 1994 for the NFL to acknowledge the risks of concussion. It then appointed the Mild Traumatic Brain Injury committee (MTBI) to study the matter. MTBI was led by Dr. Elliot Pellman, the team physician for the New York Jets who also served as the NFL commissioner's personal physician. Pellman, who was not a neurologist, stated that concussions should be considered an occupational risk. The committee's work was questioned as being industry-funded research.19 In 1997, the NFL countermanded the American Academy of Neurology's recommendation that players knocked unconscious be removed from the game, arguing that brief losses of consciousness did not warrant removal. By 1999, the NFL was making disability payments to a handful of former players who suffered cognitive decline or brain damage.20 One NFL franchise owner, Jerry Jones of the Cowboys, admitted "that he would push Troy Aikman . . . to ignore concussion concerns during the playoffs."21 Aikman retired from football in 2000, after suffering his 10th concussion.

In 2000, the American Academy of Neurology found that 61 percent of former NFL players had had concussions and 79 percent of these had not been forced to leave the game.22 Additionally, the research showed that "26 percent reported three or more concussions."23 Nonetheless, Pellman continued to urge players to return to play after a concussion and the MTBI argued that concussions had no long-term health effects. Pellman was also accused of trying to discredit the findings of noted scientists who were studying the effects of concussions.24 In 2005, Pellman and colleagues published an article that concluded, "Return to play does not involve a significant risk of a second injury either in the same game or during the season."25 Over the subsequent 2 years, however, two former football stars committed suicide. Terry Long, who had been a lineman for the Pittsburgh Steelers, was found to have CTE after he died from drinking antifreeze.26 Andre Waters, a veteran of both the Philadelphia Eagles and the Arizona Cardinals, shot himself in the head at the age of 44, and doctors determined that he had the brain tissue of an 85-year-old man.27

A 2007 journal article written by physicians affiliated with the University of North Carolina Center for the Study of Retired Athletes concluded, "Our findings suggest that professional football players with a history of three or more concussions are at a significantly greater risk for having depressive episodes later in life compared with those players with no history of concussion."28 But that same year, Dr. Ira Casson, cochairman of the MTBI, denied any link between head injuries and assorted cognitive problems.29 Eric Winston, an offensive tackle with the Cincinnati Bengals, became president of the NFL Players Association in March 2014. He was appalled that quarterback Case Keenum of the St. Louis Rams was not removed from a game after showing clear signs of a concussion.30 Winston pledged to give his brain to the Concussion Legacy Foundation for CTE research, stating,

We want the NFL to now hold the teams accountable to the protocols that are in place. Accountability and responsibility cannot fall squarely on the shoulders of players; the same standards that apply to us should apply to the teams, and to everyone.

The NFL continued to dismiss the threat of brain injury to its players until 2016, when the Supreme Court deferred to the Appeals Court decision on the NFL and NFL Players Association settlement. Only then did the NFL publicly acknowledge that CTE and other brain disorders were a threat to the functioning of its players

PLAYING SURFACE AND HELMET PROTECTION

The NFL identifies concussions by source, and by far the most common source is impact with another helmet. A distant second is impact with the playing surface?artificial turf or natural grass?and below that is impact with a shoulder or knee.33 Accordingly, scientists have been studying the effect of the playing surface. Players prefer grass (i.e., natural turf) over artificial turf because natural turf is softer. Artificial turf continues to be used in 13 of the 31 football fields used by the NFL.34 Scientists have tested three surfaces: "an indoor artificial turf practice field, a grass outdoor practice field, and the artificial turf field at a domed stadium." The scientists dropped an accelerometer 20 times from a height of four feet onto each of the three surfaces. They found that the domed-stadium artificial surface was the hardest and concluded that it "may contribute to the high incidence of concussion in football players."35

In a study of high school athletes, researchers found that 76.2 percent of concussions resulted from contact with another player, and 15.5 percent from contact with the playing surface.36 Surfaces deserve the same attention as helmets. Artificial surfaces can be softer than turf depending on cushioning and maintenance, but can be very hard if the base is not soft.37 As noted earlier, the most common source of concussion is helmet-to-helmet impact. As hard as the helmet is that protects a player, that same hard surface is what strikes the other player when two of them collide. This raises the question of how much protection is really afforded by helmets. The answer is, not much. Standard football helmets do help to prevent skull fractures, but were never designed to reduce concussions.38 Although more protective helmets have been designed, it remains to be seen whether players, coaches, and officials will be motivated to make a change.

COLLEGE FOOTBALL

College football is a feeder system to professional football. Adrian Arrington, who played defensive back for Eastern Illinois, developed a reputation for hard-hitting tackles that coaches and fans liked to see. He finished his college career with lots of tackles and four concussions. He was cleared to practice the next day after each concussion. However, when he sustained his fifth concussion during a game, Arrington's father came down to the field and not only refused to let him reenter the game, but to ever play football again. Arrington now suffers from seizures and memory loss. He is unable to work due to his disabilities and unable to pay for his growing medical bills.39 In the 5-year period ending in 2014, the NCAA estimated that there had been about 3,417 concussions in college football. However, when 730 players were surveyed, the researchers found that "only one in every 27 head injuries had been reported."40 Other studies have also revealed likely underreporting of head injuries in the NCAA and the NFL.

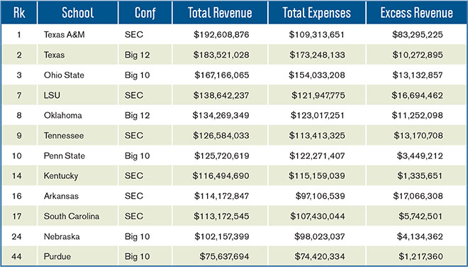

TABLE 1 NCAA UNSUBSIDIZED ATHLETIC PROGRAMS

Lawyers for college athletes filed a class-action lawsuit against the NCAA. Former Central Arkansas wide receiver Derek K. Owens, who was named in the lawsuit, told his mother, "I feel like a 22-year-old with Alzheimer's."41 The suit resulted in a 2014 settlement in which the NCAA admitted no wrongdoing, but set up "a $70 million fund to diagnose thousands of current and former college athletes to determine if they suffered brain trauma playing football, hockey, soccer and other contact sports."42 The NCAA also agreed to implement a uniform return-to-play policy for all athletes when a head injury was suspected. But, rather than awarding any monetary compensation to injured players, the settlement merely gave players the right to sue individually if the diagnostic process revealed damage. As college football players and their families have become more aware of the long-term risks of head injury, more are choosing to give up football. From the start of the 2013 season through November 2015, at least 26 players in major college football retired because of concussions.

A Business Insider study found that college football revenue was over $3.4 billion in 2013, whereas a decade before, in 2003, the revenue was under $1.6 billion.44 The schools profit at the expense of the student athletes who are essentially playing at a professional level of competition in the Southeastern Conference, Big 10, and Big 12. College football has elite teams with large numbers of viewers in the stadium and on TV. Average attendance per home game in 2016 was over 100,000 for Michigan, Ohio State, Texas A&M, Alabama, Louisiana State University, Tennessee, and Penn State.45 Yet, as mentioned previously, most Division I schools subsidize their athletic programs through mandatory student fees, institutional support, or government support.46 Table 1 lists the unsubsidized programs with their total revenues and expenses. The figures are for all sports.47 As shown in Table 1, only 12 NCAA Division I athletic programs received no subsidies. Six of those listed were from the Southeastern Conference, four from the Big 10, and two from the Big 12. Ninety-eight programs received 70 percent or more in subsidies. Many of these are at schools where game attendance is low and the win/loss record is modest. In 2014, 28 NCAA Division I teams drew fewer than 20,000 fans per game on average.

One argument in favor of robust college football programs is the idea that college serves as a feeder system for professional football. Yet only a small minority of college players end up playing in the NFL. In 2016, only 16 schools had 5 or more drafted players drafted by the NFL.49 Ohio State had the most at 12 players, followed by Clemson (9 players) and UCLA (8 players). In summary, many college programs are heavily subsidized, the college athletes have little hope of being drafted into the NFL, and they run the risk of developing CTE. So why should higher education institutions, many of which are dealing with declining budgets, continue to subsidize these football programs? One common argument is that wealthy alumni love football and increase their giving accordingly. Indeed, a 2012 working paper by the National Bureau for Economic Research found that "college football success is correlated with increases in alumni giving, applications, academic reputation and incoming students' SAT scores."50 However, the positive effects of winning football teams still do not justify the subsidies paid, according to the researchers. And only some schools are winners. An exception is a school like Clemson. Its football team was the national runner-up in 2016, and it has done extremely well with increased donations and more out-of-state applicants.51 Its 2017 national championship should make for even more enthusiastic donors. However, schools like Clemson are extraordinary. Stanford University and Princeton University economists found that "football and basketball records generally have small and statistically insignificant effects" on alumni giving.52 Similarly, a Cornell University economist found that successful college athletic programs have relatively little impact on "additional applications from prospective students and greater contributions by alumni and other donors.

HIGH SCHOOL FOOTBALL

Just as college football is the feeder to the NFL, high school football serves as the feeder for college. But most high school players are minors, which has both legal and physiological implications for the risk of injury at their age. According to an analysis of peer-reviewed studies, "high school football players suffered 11.2 concussions for every 10,000 games and practices. Among college players, the rate stood at 6.3."54 In 2016, a program called the Dignity Health Concussion Network was introduced in the San Francisco Bay area with the goal of educating high school students about concussions. Supported by the San Francisco 49ers, the California Interscholastic Federation, and ImPACT, the maker of a widely used computerized concussion management tool, the program aimed to reach 200,000 students in its first year.55 Dr. Javier Cárdenas, director of the Barrow Concussion and Brain Injury Center, one of the program's originators, said,

For example, many people believe that a head injury is only a concussion if there is a loss of consciousness, but 90 percent of concussions do not present with that symptom at all. This program empowers athletic directors and coaches to take an injured player out of the game and gives athletes the tools to speak up when something doesn't feel quite right

THE NFL'S FUTURE

The link between repeated blows to the head and CTE is clear, but TV viewers love professional football. In 2014, regular season games averaged 17.6 million viewers per game telecast.57 Viewers per game decreased in 2016, yet the average was still 16.5 million.58 The 2017 Super Bowl was viewed by an estimated 111.3 million viewers.59 As of June 2017, the YouTube video, "10 Knockouts in the NFL—BIG HITS," has had more than 12 million views.60 The video is horribly brutal, yet many NFL fans enjoy the violence of the game.

High salaries and fame will continue to attract players. In 2017, the average NFL salary was $1.9 million.61 Helmets will improve. Rules will protect vulnerable players. Players with multiple head injuries may be put on disability. Medical studies will continue and so will the NFL, despite CTE. It is possible that future diagnostic testing could warn players that are at risk for brain injuries.62 But such tests are still in the early stages of development. Meanwhile, similar to the trend with college athletes mentioned previously, growing numbers of NFL players are deciding to retire early rather than subject themselves to further risk; they include such big names as Calvin Johnson and B. J. Raji.63 San Francisco 49er linebacker Chris Borland retired in 2015, after playing only one season, and returned three quarters of his four-year signing bonus, stating that he did not want to risk the physical repercussions related to CTE.

Critical Thinking Questions

1. Hypothetically speaking, assume that your son is gifted athletically and could potentially earn a college scholarship for football. Would you allow him to play high school football?

2. Is brain injury simply an occupational hazard in the NFL? Do prestige and high pay justify the risk NFL players take in terms of potential brain injury?

3. What more can the NFL do to protect players from brain injury? Or, has it done what it can for the moment?

4. Assume that you are a college president and your institution's football team has a losing record with low attendance at games. Approximately 70 percent of the expense of running the team must be subsidized, and players are subjected to potential brain injury. Should the football program continue?

5. Assume that your college's football team won its conference title and has gone to several bowl games in the past few years. Success has had a positive impact on school spirit and wealthy donors are enthusiastic supporters. Three or four players are drafted by the NFL in a typical year. However, players continue to risk brain injury. Should the football program continue?

Rk School Conf Total Revenue Total Expenses Excess Revenue 1 Texas A&M SEC $192,608,876 $109,313,651 $83,295,225 2 Texas Big 12 $183,521,028 $173,248,133 $10,272,895 3 Ohio State Big 10 $167,166,065 $154,033,208 $13,132,857 7 LSU SEC $138,642,237 $121,947,775 $16,694,462 8 Oklahoma Big 12 $134,269,349 $123,017,251 $11,252,098 9 Tennessee SEC $126,584,033 $113,413,325 $13,170,708 10 Penn State Big 10 $125,720,619 $122,271,407 $3,449,212 14 Kentucky SEC $116,494,690 $115,159,039 $1,335,651 16 Arkansas SEC $114,172,847 $97,106,539 $17,066,308 17 South Carolina SEC $113,172,545 $107,430,044 $5,742,501 24 Nebraska Big 10 $102,157,399 $98,023,037 $4,134,362 44 Purdue Big 10 $75,637,694 $74,420,334 $1,217,360

Step by Step Solution

3.40 Rating (144 Votes )

There are 3 Steps involved in it

Step: 1

As a parent the decision to allow your son to play high school football involves weighing the potential risks and benefits Considering the documented risks of brain injury associated with football its ...

See step-by-step solutions with expert insights and AI powered tools for academic success

Step: 2

Step: 3

Ace Your Homework with AI

Get the answers you need in no time with our AI-driven, step-by-step assistance

Get Started