Answered step by step

Verified Expert Solution

Question

1 Approved Answer

Chapter 7 Chapter 8 Questions for Chapters 6,7,8 After completing all of the assigned readings, please answer the following questions carefully and in your own

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 8

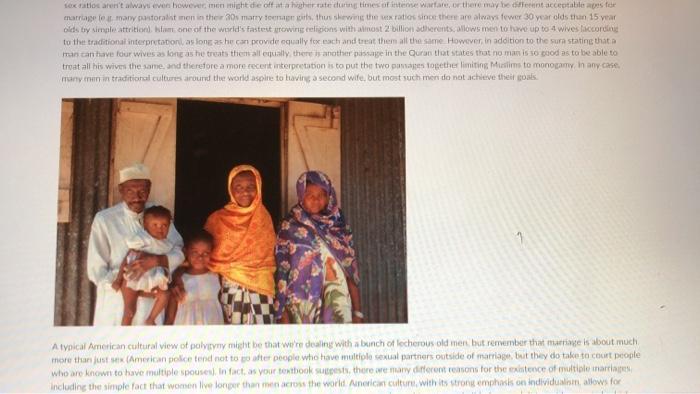

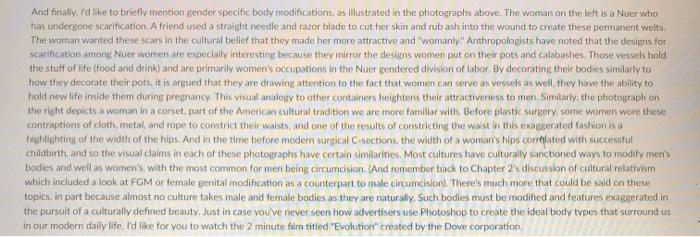

Questions for Chapters 6,7,8 After completing all of the assigned readings, please answer the following questions carefully and in your own words. The length of the answer I m looking for depends on the question, sometimes only a sentence is needed, but usually a paragraph or more is called for. Each question is worth 5 points, so please spend sufficient time on your answers. 1. From Richard Lee s reader article, why had he chosen to not share his food with the !Kung San before the ox feast which is the subject of his story? 2. What is the difference between sex and gender? Why is it important to understand this distinction? 3. What are some of the ways in which social order is maintained in band and tribal societies? 4. According to our article When Brothers Share a Wife, what is the reason for the practice of fraternal polyandry? How did it develop? 5. Does the practice of bridewealth necessarily imply gender inequality? What is the function of bridewealth, what type of society does it typically occur in, how does it affect marriage and divorce, and how does it differ from a dowry? 6. Please explain how the emic and etic perspectives can be combined to enhance our overall understanding of the Kpelle hot knife ordeal and help explain why the ordeal specialist is so often successful. 7. From our lectures and textbook, what are the three dimensions of social stratification as defined by Weber? What is the basis of each dimension? How does stratification differ from status systems in nonstate societies? 8. From the critical thinking section of Williams article. How have Europeans and American Indians differed in their treatment of the berdaches? How does the author explain these two different approaches? Text Entry Chapter 6 - Sociopolitical typology In looking at all of the political diversity in the pre-industrial world, anthropologists have come up with a useful sociopolitical typology that relates well to the typologies we developed in the last chapter for subsistence adaptive strategy and economic exchange systems. As with those typologies, reality is more complex than our models indicate, and so there is a bit of grey area between each of these ideal types as they merge into one another. In general though, I like to view the concepts of bands, tribes, chiefdoms, and states as something of a sliding scale going from small and simple to large and complex. (And simple here is not meant to be pejorative, it just indicates a lack of economic specialization, meaning everyone does pretty much the same thing as everyone else in the group each day.) Bands are usually small scale, egalitarian, nomadic foragers who utilize reciprocity. Tribes are often mobile pastoralists or village horticulturalists who are egalitarianist and rely on reciprocity and redistribution. Chiefdoms are ranked kin groups usually based on agriculture with much redistribution. And states are large, territorial, multi-ethnic political entities with social stratification, based on agriculture, and most often with a market-based economic system. Another way of seeing the difference between these four sociopolitical types is to consider what sorts of leaders each possesses, and to do this I d like to use Max Weber s three dimensions of social stratification or inequality. Weber (pictured above) was a 19th century German theorist whose theories serve as a counterpoint to the work of his contemporary Karl Marx. Marx was a materialist-it was the stuff, who has it and who doesn t, that matters most in human affairs and history. Thus we have Marxist slogans like Workers of the world unite! urging the alienated workers around the world to recognize the exploitation inherent in the capitalist system and to rise up and take control from the capital owners to create a more fair and just economic system. However, the envisioned global workers revolution never materialized, in part because the Catholic workers were too busy fighting Protestant workers in Northern Ireland, Hindus and Muslims in India, whites and blacks (so-called) in the United States, and so on. Max Weber was an idealist (as opposed to Marx s materialism), meaning that he felt ideas such as culture and religion were the driving force in human history, and this included the many social divisions based on such things as race, ethnicity, language, religion, and so forth. In looking at social divisions, Weber realized that in Europe and North America people could accumulate different amounts of wealth, power, and prestige. The three usually co-occurred, but some individuals possessed one or two without necessarily having the others. For example, in our system religious leaders often have great power and prestige, but those two are threatened if they also become wealthy, as that can lead to questions of corruption and fleecing the flock Kottak discuss Weber s classic triad in this chapter (the independent dimensions of wealth, power, and prestige), but he could have gone further to link that typology to the main sociopolitical typology of bands, tribes, chiefdoms, and states. I think one of the best ways to understand the differences between bands, tribes, chiefdoms, and states is to look at how at each level the leaders of the society are able to accumulate one more of Weber s dimensions of inequality, Leaders are culturally allowed to gain new abilities as their group becomes larger and more complex (and that is largely the point of the case study in your textbook concerning the Basseri and Qashqai in Iran). To start with bands. because they are so egalitarian no one is allowed to accumulate much wealth, power, or prestige over anyone else. In this sense there are no true leaders and everyone has a great deal of self-determination, though there are a few special positions such as part-time religious-healers called shamans that we ll cover when we get to the chapter on religion. All individuals differ in terms of abilities (some will be good hunters and others not so much, but egalitarian bands have cultural features in place to prevent the accumulation of wealth, power, and prestige based on these individual differences. As we saw in the last chapter with Lee s article on the Kung San Bushmen, there are leveling mechanisms in place to prevent the emergence of inequality, and therefore also of true leadership Moving from bands (without a single dimension of stratification) to tribes, we now find leaders who are allowed (and encouraged) to accumulate prestige, but not wealth or power. In Tribes, leaders emerge (such as the village headmen among the Yanomami pictured above with the anthropologist Napoleon Chagnon, or found in the big man systems of the South Pacific) who are widely respected and use their prestige to lead by example. Yanomamoi headmen cannot order others in their group to do anything, they simply lack the power. But they do have influence. If a neighboring village is coming for a feast, the headman will probably be the first cleaning up the central clearing. Others will see his work and say, our headman is cleaning up for the guests, we should go help him, and once a small work group gathers the headman might go off to start another project. Such influence comes from social prestige, and the culture encourages ambitious men to pursue such status by giving redistributive feasts and other actions. In Chiefdoms, these prestigious and influential leaders gain real political power for the first time, in that they can issue commands and order others around, what to grow, who to fight, what tribute must be given to the chief himself. But a chiefdom system is still based on kinship (you re part of the group only because you re related to the chief, even if distantly). Because of this, the chiefs are still obligated to help and share their resources with every member of the group. This is a big difference between chiefdoms and states: the lowest ranking member in a state such as a slave or peasant can come to the king and say feed me, I m hungry, and the king can reply off with his head. But in a chiefdom, the lowest ranking member can come to the chief and say, I m your fifth cousin, twice removed, and I m hungry, please feed me and there s strong pressure on the chief to take care of his kin Chiefly redistribution also makes the economy more efficient, because the chief can order each farmer to only grow the crops for which their land is best suited, and he will then redistribute out to people the items they need but didn t grow themselves. All of this was possible because the chief was allowed to accumulate both prestige and power, but he wasn t yet allowed to have great material wealth differences from everyone else in the system. The chief, which was an inherited position and a permanent political office that had to be filled by someone, did maintain his royal household from the surplus that was tributed to him by each member of the chiefdom, but much of that food was stored for emergency use for the benefit of the entire group in times of crises. Any wealth differences between a chief and his subjects was relatively minor compared to the differences in prestige and power. Everybody in Hawall (one of the classic examples of a complex chiefdom) before the arrival of Europeans lived in similar houses, but once we get to state level societies we see the king gets a castle or grand palace while others are homeless or in hovels. To recap, bands have no formal leaders while tribal leaders gain prestige and chiefs are allowed both prestige and power. In the largest and most complex socio-political form-states-leaders emerge who have great prestige, power, and wealth differences from others in the system. Because of social stratification and the territorial rather than kinship basis for membership, ruling elites in states have fewer obligations to the lower social classes Your textbook mentions that chiefdoms are somewhat transitory in the ethnographic record, a temporary position between tribes and states in most places (one main exception is on islands where many cultures seem to have stayed at a complex chiefdom level rather than forming fully-fledged states). I think this becomes more understandable when you combine Weber s triad with Service s sociopolitical typology as we ve just done. In most places as tribal leaders become chiefs, and gained real power for the first time, they also gained new powers to change the rules of the game. A chief with prestige and power might decide he now gets to keep the wealth as well, and in the right circumstances he might now have the power to deny that distant And I should clarity how I ve been using these words-bands, tribes, chiefdoms, and states as well. These words have a technical meaning in anthropology that differs slightly from how they are used by the general public in everyday conversation. For example, Missouri is a political sub-entity called a state but that use is different from anthropologists talking about the Aztecs of central Mexico having been a state Please review your textbook s definition of state and realize how it differs from other uses of the word. Likewise, the word tribe has come to mean more generally a group that is non-Western and somehow primitive, but that s not how I ve been using the word here where it signifies a specific sociopolitical formation falling between bands and chiefdoms in complexity. In other words, just because a group is in Africa doesn t mean (to anthropologists) that they are tribes or tribal African groups, as did groups on all other continents, formed themselves into all four sociopolitical types, and so you can expect African states and bands along with many tribes. For example, the photo above is of a man who was part of the Sakalava state on the west coast of Madagascar. He s standing next to a statue of an earlier Sakalava warrior, and the Sakalava state had all the trappings of states elsewhere (territorial boundaries defended by a standing army, centralized decision making centered in a government bureaucracy led by a royal king, substantial social stratification, and so forth). (I m also including this photo because the man, despite a difference in skin color, always reminds me of the Scottish actor Sean Connery, a Malagasy James Bond in the king s service, if you will. The biased general conception that all Africans must live in tribes often shows up in media reports. For instance, when the Hutus and Tutsis (both long standing state level societies) were killing each other in Rwanda, our newspaper headlines read Tribal Warfare in Central Africa. But when something very similar happened in the former Yugoslavia between Croats and Serbs, the same newspapers labeled it Ethnic Cleansing The notion that if it s in Europe it must be ethnic groups but if it s in Africa then it must be tribes shows the problems with the popular definitions of these words. Anthropologists are using them in a much more precise way, and therefore we ll try to define the terms we re using as we work our way through this course. As one final topic for this lecture I d like to consider further the justice systems and conflict resolution in non-state societies. Kottak does a good job of showing how conflict resolution happens among the band-level Eskimos (or Inuit), but I d like to add an example of a type of law and justice common in tribal and chiefly societies- trial by ordeal, For many groups there are culturally prescribed punishments for crimes, usually including banishment as the most severe - the individual is no longer allowed to live with the rest of the group. The problem, however, often comes in how to determine guilt and innocence. Many groups therefore have devised tests that call on the supernatural to help them determine guilt and innocence (and yes, Monty Python did make fun of such ordeals in their movie Quest for the Holy Grail when they argued that a witch was someone who weighed the same as a duck). Instead of Monty Python and medieval Europe, I d like to look at the Kpelle of West Africa and their hot knife ordeal. In a classic ethnographic film on the Kpelle, a local chief s cow had gotten loose and rampaged through a number of people s gardens. In response someone had grievously struck the cow with a machete blow, and the chief was intent to find out who had done it so that they could be punished. (The textbook chapter does mention this sort of scheduling need between pastoralists and neighboring horticulturalists. If the cows get into the fields too soon they will eat crops meant for human consumption, but if their arrival can be timed after the harvest then they will be welcomed to eat the stubble and leave behind the fertilizer). In the Kpelle case, when no one confessed, the chief called in a ritual specialist to administer the hot knife ordeal to the likely suspects. The specialist interviewed each of the suspects as part of his investigation, and then he took a knife blade heated in the fire and rubbed it slowly back and forth on each suspects thigh. Everyone in the culture believes that the guilty party will be burned by the knife but the innocent will be spared. These Kpelle ritual specialists are surprisingly accurate and can identify the person who actually appears to be the guilty party in most cases. From the emic perspective, the Kpelle have faith that their understanding of the supernatural world is accurate as shown through the workings of these ordeals. From the etic perspective, I d argue that some people are burned and others are not because the ritual specialist imperceptibly changes that rate at which he rubs the knife back and forth, or heats the blade up to different degrees in the fire. But still, how does he know, even subconsciously, who to burn and who not to? Again, from an etic perspective. I d argue that the hot knife ordeal specialists are so successful because they can perform like human lie detectors. By closely observing the breathing rates, pupil dilation, and other physical changes monitored by modern mechanical lie detector systems, while they are asking questions of those undergoing the ordeal, they can use these close observations to arrive at an accurate accusation of guilt. You can imagine that the people who are naturally good at such things are more likely to go into this line of work among the Kpelle, and the fact that they can so often tell when someone is lying means they d probably be really good poker players as well. Chapter Seven - Marriage and Kinship Some of the topics in this chapter are controversial because Americans recently went through the process of redefining marriage for ourselves through first state legislatures and then our Supreme Court As with other subjects though, anthropologists are not claiming any one way is the right way, they are simply trying to inventory the diversity found around the world, organize it into some form of typology leg, polygyny vs. polyandry), and then try to tease out the connections to other realms of culture and to tackle the big why questions. Cross-culturally, marriage does seem to be a cultural universal (eg every group has some relationship that comes close to what we mean by the word marriage ). Anthropologically, it is often a specially recognized relationship between men and women leven for same-sex marriages among males and females) that serves to - Legitimate offspring and provide for their upbringing -Establish rights to the sexuality, labor, and property of others. -Link families For most cultures, the most important function of marriage is the linking of families, and as such it becomes more of a group affair than an individual affair. (And note that this definition makes a distinction between men and women as gender terms based on a cultural role versus male and female as biological terms), Evidence of marriage being an alliance between groups rather than individuals in many cultures can be found in the widespread practice of arranged marriages, rather than the love matches most Americans are familiar with, as we read about in the Nanda article in our reader. Marriages everywhere create new social ties, new relations (spouses and in-laws) that provide a setting for important sexubl, economic and educational activities. And these new connections are often the most important function of marriage for a group. An important consideration for many groups concerning marriage is how many people one should marry. The common American system has been called serial monogamy or one after another since many Americans are eventually married to multiple husbands or wives because of divorce and remarriage but they re just married to one at a time however, Polygyny (one man married to multiple women at the same time) is actually the most common ideal for a majority of cultures around the world, while monogamy is by far the most common marriage form in practice. This results, in part. from simple numbers: if 1 man has 20 wives, and the sex ratios are close to even, doesn t that lead to 19 other men who have no wives? In practice. it would probably work out something like 1 man with 20 wives. 75 men with a single wife each, and 24 unmarried men (which would work out to a total of 21 people involved in a polygynous union, 150 people in monogamous marriages, and a sizable number of unmarried men in the group). Don t worry about the math, just know that even for those cultures where men desire to have a second wife, and feel that it is the right and proper thing to do, very few will actually be able to achieve their goal. Regardless of a culture s preferred form, most men and women are involved in monogamous unions. The sex ratios aren t always ever however, men might die off at a higher rate during times of intense warfare, or there may be different acceptable ages for marriage (eg many pastoralist men in their 30s marry teenage girls, thus skewing the sex ratios since there are always fewer 30 year olds than 15 year olds by simple attrition) islam one of the world s fastest growing religions with almost 2 billion adherents, allows men to have up to 4 wives according to the traditional interpretation, as long as he can provide equally for each and treat them all the same. However, in addition to the sura stating that a man can have four wives as long as he treats them all equally, there is another passage in the Quran that states that no man is so good as to be able to treat all his wives the same, and therefore a more recent interpretation is to put the two passages together limiting Muslims to monogamy, in any case. many men in traditional cultures around the world aspire to having a second wife, but most such men do not achieve their goals A typical American cultural view of polygyny might be that we re dealing with a bunch of lecherous old men, but remember that marriage is about much. more than just sex (American police tend not to go after people who have multiple sexual partners outside of marriage, but they do take to court people who are known to have multiple spouses). In fact, as your textbook suggests, there are many different reasons for the existence of multiple marriages including the simple fact that women live longer than men across the world. American culture, with its strong emphasis on individualism, allows for individual choice on who to marry and on whether to get married at all. But in some cultures it s not permissible for an adult to not be married, which means that the many widows near the end of their lives must still get married to someone else once their first husband passes away, in line with the common (and Biblical) levirate custom, many of these elderly women marry a brother or much younger nephew from their dead husband s family. These marriages need not be sexual, and the individuals involved may have no such interest in their new partner, but each will perform the work of a husband or wife for their spouse and other expected duties. In other cases, polygyny results from politically ambitious men (more in-laws means more supporters than your competition) and even from the desires of the first wife herself rather than the husband, as I learned when taking the photograph above. On my first trip to Madagascar while in graduate school many years ago I met the family pictured above in the small village of Maronduka on the northwest coast of the island. My Malagasy and French were both weak, and the inability to communicate was starting to bother me, when I happened to visit this town with many Swahili immigrants including the elderly man pictured here. I had learned Swahili while in college, and was so thrilled to finally be able to talk to someone that I stayed for a few days and got to know this man a bit. Next to him is his first wife and his younger second wife, and in this one specific case I can say that the man didn t want to take on a second wife, but was forced into it. He had saved up a sizable sum of money to buy a dhow to use as a fishing boat, but his wife essentially said. if you buy that damn boat I ll divorce you because she wanted him to use the money for bridewealth to gain a second wife (and bridewealth is another important term from the chapter that I ll discuss a bit more below). So why was she so insistent? Essentially it was because she was getting older and wanted to retire somewhat. As the senior wife in the family she would have some authority over any junior wife that joined them and she would gain assistance with the women s work that needed to be done in the household. In our culture a family might solve this problem through capitalist wage labor by hiring a maid, gardener, or cook, but this Swahili wife solved some of her problems by forcing her husband to take another wife. But why did the younger woman s family arrange such a marriage knowing that a junior wife would be at a disadvantage in relation to the senior woman in the family? (and note that I m still talking about this one specific case, a very different personal dynamic is often found among wealthy, westernized, West Africans, as has become the subject of many novels). It has to do with marriage as alliance formation again. In this case, the husband s family had greater standing in the society, more wealth, power, and prestige to use Weber s terms. and the family of the younger women wanted such a political connection (plus they knew the people involved and could reassure the young woman that the senior wife was a nice lady who wouldn t abuse her). When I met him he was still acting grumpy about not being able to get his boat, but his wife got her way in the end. So what about that bridewealth (which is the transfer of wealth in conjunction with marriage from the husband s family to the bride s as opposed to dowry in which the wealth moves in the opposite direction)? (And please note that your textbook refers to the Bridewealth institution by the more culturally specific term lobola. ) Bridewealth might be seen by many Americans (ethnocentrically I d argue) as the simple buying of a woman, but for those cultures that actually practice bridewealth, it is more often seen as compensation given by the husband s family to the wife s family to make up for the loss of her productive labor and the loss of her future children. Women who have worked for their family all of their lives will now move in with their new husband s family and work for them la patrilocal system), and her family of orientation would like some economic compensation to make up for their loss. Also, in a patrilineal system all of her children that result from the marriage will belong only to the husband s family, and so they accept the bridewealth as an acknowledgement that they will make no future claims on children produced by their daughter. Thus bridewealth tends to show up in cultures where women are viewed as productive members of the family, versus those cultures with a dowry system where women are viewed more as dependents taken care of first by their father and then by their husband and so at marriage the father of the bride gives wealth to the new husband so that he can continue to take care of the woman in the manner to which she s become accustomed). Many European cultures traditionally included a dowry systems, and we still have vestiges of that today- for example, which family in American culture is traditionally supposed to pay for the wedding that might run to thousands and thousands of dollars, and why is it that only one side is expected to bear the bulk of the cost for such an event? One final point on bridewealth systems is that they tend to make divorce far less likely. Your textbook mentions this, but doesn t explain the details behind this fact, as can be seen by looking at the case of the Nuer, a pastoral group in northeastern Africa. The Nuer traditionally have given 40 cows as bridewealth, and as your textbook explains those cows might be donated by many different men in the new husband s family, and then upon receipt they are often used by the wife s family to pay their own bridewealth debts to more distant families. As might be imagined, if a divorce is to occur, then the 40 cows paid in bridewealth must be returned, but the hitch is that is has to be those specific 40 cows that are returned, and if one has passed away then you d at least need a close offspring of the original cow. You can imagine the dynamic here a woman returns to her family and says she wants a divorce. Her kinsmen think of all the work involved in tracking down and trading with other families to get back the 40 individual cows involved and think there s no way they have time for all that. Both the family of the husband and wife (since marriage is an affair between groups rather than individuals for most cultures) put strong pressure on the two individuals to resolve their differences and avoid a divorce. And in the common case of infertility, a family might offer up a substitute partner to ensure the birth of children and avoid the hassle of a divorce. You ve probably already noticed that this chapter has more technical terms and definitions than any other section in the course. In addition to the ones I ve already mentioned, you ll also need to memorize the rest, though taking them in pairs can help: matrilocal and matrilineal are in many ways just the opposite of the patrilocal and patrilineal Nuer I ve been discussing. And while these two cultural forms are less common, they are by no means rare, as many ethnographically famous cultures are matrilineal such as the Hopi in North America, the Trobriand Islanders in the Pacific, and the Akan of West Africa. Another set of terms I d like for you to learn concern the rules for what sorts of persons to marry, Le. the rules of exogamy and endogamy. The first gives you the group of people you have to marry outside of (say your family, descent group, lineage, etc), while the latter makes sure you don t go too far out in finding a marriage partner (ie, the pressures found in different groups to marry someone of the same religion, language, ethnicity, socioeconomic class, region, and so forth) Endogamy is more formal and important in many other cultures, but I think it s worth remembering the strength of racial endogamy even here in this country. It wasn t until the election of November 2000 that the last U.S. state removed its laws against interracial marriage from their books, and even in that election, 40% of the voters voted to keep marriage between people of different skin colors illegal. Clearly there is a very strong cultural rule at play here, even in American culture. Among the many terms you need to learn for this chapter is the opposite of polygyny discussed above namely polvandry which is where one woman has multiple husbands (And if it helps, when I first learned anthropology I memorized these two terms by rating that Jenny is a girl s name, and polygyny means there s many women involved, whereas Andy is a boy s name and in polyandry there are multiple men) Polyandry is relatively rare across the world, far less common than matrilineal cultures. The photograph above shows an extended polyandrous family among the Paharis in Nepal (and the photo is taken from one of Kottak s other textbooks). Standing in back is the mother and the two fathers, and seated in the foreground is the new wife with her three husbands, the youngest in her lap. As with late widow marriages mentioned above, those two may be married but they re not allowed to have sexual relations until both partners have gone through their coming of age ceremony, a rite of passage that turns boys to men and girls to women Bly marrying the oldest boy, this young Paharis woman has also married all of his younger brothers, meaning she has to wait awhile for her youngest husband to grown up. Kottak briefly discusses some of the functions of polyandry for some groups it ensures that there s always a man about to do the men s work, for those cultures that have a strict gendered division of labor but also high male mobility where individual men are away from the household for long periods of time. For other groups, especially those in the Himalayan Mountain region like the Paharis, polyandry is thought to be an adaptation to the scarcity and value of prime farm land along with the cultural rule that all boys inherit equally from the estate. The article by Goldstein) in our Reader concerns that sort of situation, and I ll refer you to that reading for more information Along with marriage, Chapter 7 also covers kinship which is one of the core sub-systems of every culture. Kinship is usually one of the first things, along with language, that an ethnographer tries to learn when they arrive at a new fieldwork site. It s so important to learn early on because it can be the key to better understanding social behavior and expectations and for gaining an insider s perspective (the emic perspective) on a culture. However, it s also fair to say that it s not as central to the practice of anthropology as it once was. Anthropologists were once thought of as the romantic explorers who study the kinship patterns of far-off peoples, and kinship took up far more space than a single chapter in older textbooks. But today, kinship studies in anthropology are usually seen as a means to an end, rather than as an end goal in themselves, and I agree with Kottak for hortening the kinship section. This is probably also a reaction to the fact that many students are turned off by all the new terminology needed for kinship studies. But many of these vocabulary words are really just ways to categorize the different approaches to defining families and obligations. You can have different types of relatives affinal (through marriage) or consanguine (through blood) Your family can have different rules of membership: patrilineal (you re only part of your father s family) or matrilineal (you re part of your mother s)... while most Americans however, are bilateral - we claim membership in both families, which is pretty rare looking on a global scale. Your extended family can be organized into a lineage or a clan depending on size and on whether you know how everyone is related or you simply believe that everyone is descended from your ancestor the bear (for the bear clan that is). Learning these different systems is important because it helps (to take just one example) explain why uncle is such an unsatisfactory translation for mother s brother in most matrilineal groups. For these groups, such as the Trobriand Islanders studied by Malinowski, mother s brother is often the male role model for children, as he s the male family member of the ascending generation (as one s biological father belongs to a different family, and he s more interested in many ways in his sister s children who are part of his family). It s this man, my mother s brother who takes a great interest in my life and is a responsible for my upbringing. He disciplines, he rewards, and the English term uncle just doesn t capture his true role in the family, Kinship can sound Chapter 8 Gender and Sexuality The cultural construction of gender and sexuality are important subjects for anthropology, and chapter 8 covers a large number of topics, some of which may be a bit unsettling for you to read. Behaviors such as the Etoro institutionalized homosexuality discussed at the end of this chapter show the power of culture. As a group of people, the Etoro are not dominated by any genetic variant leading to homosexuality, but culture is precisely those sets of rules that tell us how to act and what to think, and fewer people than you might imagine are true rebels who can go against their cultural beliefs. This topic of sexuality was largely neglected by many anthropologists until relatively recently, and that tells us something about our culture. American anthropologists have been reluctant to write about these issues in part because our own culture discourages such discussion Other cultures are often far more open about discussing sex (and some cultures, of course, have even more of a taboo than we Americans dol. On the Pacific Island of Samoa where the early anthropologist Margaret Mead did her famous ethnographic fieldwork, such discussions were open and frank But it was the difference in gender roles observed by Mead that made her well known in the United States. As we now understand better, teenage boys and girls elsewhere act differently land are supposed to act differently) according to their culture, and thus the lives of American teenagers are not the natural norm for the human species. I m sure this doesn t surprise you having now made it all the way to Chapter 8 in a Cultural Anthropology course, but the early 20th century American audiences found her message of cultural diversity both interesting and shocking at the time. As a side note. Margaret Mead was one of Kottak s teachers at Columbia, and she does get favorable mention throughout our book. Mead s advisor was Franz Boas (that founding figure who worked with the Kwakiut), and so you can see from this how young of a discipline anthropology really is from Boas to Mead to Kottak to me and to you: maybe 5 generations at most. But I think the work of Margaret Mead and Ray Kelly, the Michigan ethnographer who studied the Etoro, also demonstrates the need for team studies in ethnography. The social statuses of the anthropologist (young or old, man or woman) does affect how people talk to them in different cultures and what information they have access to. As mentioned in your textbook, Ray Kelly lived in the men s village and had very little access to Etoro women s perspective on sexuality, and thus it seems we have something of a one-sided account. We also need to keep in mind that a certain culture observed in the 1920s or 1960s is undoubtedly different today, and often radically so. Here too, as team studies become longitudinal studies, we can learn new and important things, including a better understanding of how and why a specific culture changes. Unfortunately for the Etoro, this small group has neither been re-studied longitudinally nor by a woman ethnographer, so Ray Kelly s depiction stands on its own (though it does fit the local cultural patterns of the neighboring tribes). Kottak briefly considers an Etoro perspective on sexuality in your textbook, but I d like to go into a bit more depth to help illustrate the differences again between the emic and etic perspectives in anthropology. The Etoro believed that life itself comes from sacred life-giving fluids, of which blood and semen are two manifestations. Females are born with a great deal of this life force, but they lose a small bit each month in their menstrual blood, and then lose a great deal in childbirth and the creation of a new human. Eventually, their reserves are used up, as evidence by the end of their monthly period and the fact that they can no longer produce children (and we ll return to these post-menopausal women below). Males however, according to the emic Etoro view, are not born with such great reserves and need to take in more of the sacred fluid to allow their bodies to transform into the bodies of men (and Etoro pointed to the onset of puberty as proof that the ingestion of semen by boys led to the needed physical changes in their bodies). The Etoro were not unusual in terms of these beliets in this part of New Guinea. Their neighbors the Marind-amin and the Kiman both had similar beliets in how boys turn to men, but the latter spread the sacred fluid on the exterior of the boys bodies while the former put it elsewhere. In a good example of ethnocentrism, the Etoro believed the Kiman to just be ignorant about how the world actually works and believed the Marind-amin to be perverted for their practices. Ethnocentrism is universal and culture does shape a group s and individuals sexuality. So what about Ray Kelly s etic perspective on this? To understand the function of this cultural feature, one needs to look at how it played out in the society. Because the loss of a man s sacred fluid (blood or semen) leads slowly to his death, men viewed with suspicion any woman who wanted to engage in heterosexual relations beyond the need for reproduction (Etoro men saw their work in producing new babies and in aiding the maturation of young boys as a necessary sacrifice, they were giving up some of their own life in order to help their group continue) Whereas the homosexual acts were encouraged to create a new generation of warriors, heterosexual unions were tabooed for a majority of the year and spatially they could only take place in certain dangerous locations. So what came of this? Not many babies as you might guess. Ray Kelly argued that Etoro homosexuality was an adaptation (an extreme or unusual one perhaps) to a situation of extreme overcrowding and resource scarcity. In other words, it arose as a form of birth, control. A method that cut the birth rates for the Etoro while still allowing for a culturally approved expression of human sexuality (at least for the men, as far as we know). Kottak also briefly mentions the existence of third genders in this chapter, and I think the Etoro can help us understand that cultural feature better as well. I mentioned above that the Etoro (and their neighbors in this case, such as the Sambia studied by Gilbert Herdt, 1987) believe that women lose their sacred life force in blood throughout their lives, until their monthly period ends. But what are they then? These New Guinea groups see women as people who menstruate and can produce children, thus post-menopausal women are no longer women from their perspective. These people are considered a third gender (called kwolu-aatmwol by the Sambia), and as such they often move out of the village for women and children where they have lived their entire lives, and move into the men s village, not as men themselves, but as a recognized third gender, as a different sort of person. Being post-menopausal, these people now gain certain powers and cultural abilities that were denied to them earlier in life. Many other groups also have a third gender category for pre-pubescent boys and girls las opposed to American culture that tends to genderize our infants from day one with a pink or blue blanket). While we see these young people as little women and little men, other groups see them as one undivided group of kids half of which will later turn into the gender of men and the other half women Still other cultures have third gender categories for culturally approved trans individuals such as the Native American berdache institution (a biological male living life similar to a woman, but not a woman, a berdache) or the opposite of a manly-hearted woman. With this chapter we ll read an article on this Berdache tradition, but this title brings up issues of the political use of words and our need to be careful and considerate Bordache was originally a derogatory terms so some anthropologists today would like to avoid the term, instead of using Berdache one common textbook discusses the sorts of variations that had been labeled berdache cand yes, this did make me think of the artist formerly known as Prince ), and our own textbook chooses to go with two-spirit people Words are powerful and it seems reasonable that people should have some say in what labels and terms are applied to them by others. We ve encountered this issue before in the use of culture names such as Eskimo. The common names of many groups are derogatory names and were given them by their neighbors: Eskimo means something like eaters of raw meat a name used by the Athabaskan speakers to the south who first told it to European explorers. Eskimos call themselves Inuit, which simply means people and has been more broadly adopted in Canada and elsewhere. Likewise, the name Navajo was given to that Native American group by their puebloan neighbors, while they call themselves the Dine, which means, not coincidentally, the people. In the same vein, your textbook talks about the Ju/hoansi San while the earlier article by Lee referred to the same people as the Kung San In lecture I ve mentioned the Kwa Kwaka Wakw while the textbook refers to that group as the Kwakiuti studied by Boas. The goal is not to create confusion with a profusion of new names, but to try to use non- offensive names where possible out of respect. In practice, however, I tend to use the more traditionally established names despite their problems, since they re more effective in a literature search (such as Berdache ), though in many cases the more appropriate name, such as Inuit, is becoming more widely known today, it is an interesting point, though, who should have the power to decide which names we use and what we can call people? Another definitional point is that I have been discussing in this lecture an anthropological approach to gender studies, and not feminist studies. Feminism is not just the study of men and women and how they interact (which would be gender studies) but feminisms includes additionally a political commitment to equal opportunity and access. A feminist approach is one that includes the belief that a certain social system has inequalities based on pender, and that such inequalities should be eliminated as much as possible. Personally, by that definition, I consider myself a feminist in our society. But one of my first publications was a book from Michigan (with a bunch of other grad students) entitled A Gendered Past, a name specifically chosen because we wanted to look at gender relations in the past without the political commitment and judgment of the issues that the word feminist would convey. Whether in anthropology or another academic discipline, the careful use of words is important and it s good to think more about what they say. And finally, I d like to briefly mention gender specific body modifications, as illustrated in the photographs above. The woman on the left is a Nuer who has undergone scarification. A friend used a straight needle and razor blade to cut her skin and rub ash into the wound to create these permanent welts. The woman wanted these scars in the cultural belief that they made her more attractive and womanly. Anthropologists have noted that the designs for scarification among Nuer women are especially interesting because they mirror the designs women put on their pots and calabashes. Those vessels hold the stuff of life (food and drink) and are primarily women s occupations in the Nuer gendered division of labor. By decorating their bodies similarly to how they decorate their pots, it is argued that they are drawing attention to the fact that women can serve as vessels as well, they have the ability to hold new life inside them during pregnancy. This visual analogy to other containers heightens their attractiveness to men, Similarly, the photograph on the right depicts a woman in a corset, part of the American cultural tradition we are more familiar with. Before plastic surgery, some women wore these contraptions of cloth, metal, and rope to constrict their waists, and one of the results of constricting the waist in this exaggerated fashion is a highlighting of the width of the hips. And in the time before modern surgical C-sections, the width of a woman s hips correlated with successful childbirth, and so the visual claims in each of these photographs have certain similarities. Most cultures have culturally sanctioned ways to modify men s bodies and well as women s, with the most common for men being circumcision. (And remember back to Chapter 2 s discussion of cultural relativism which included a look at FGM or female genital modification as a counterpart to male circumcision). There s much more that could be said on these topics, in part because almost no culture takes male and female bodies as they are naturally. Such bodies must be modified and features exaggerated in the pursuit of a culturally defined beauty. Just in case you ve never seen how advertisers use Photoshop to create the ideal body types that surround us in our modern daily life. I d like for you to watch the 2 minute film titled Evolution created by the Dove corporation

Step by Step Solution

★★★★★

3.38 Rating (148 Votes )

There are 3 Steps involved in it

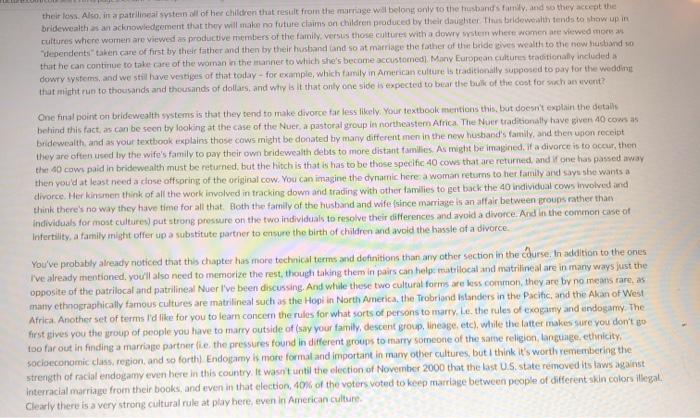

Step: 1

1 Richard Lee chose not to share his food with the Kung San before the ox feast in order to observe their behavior and reactions to the feast without any potential bias that could have been caused by ...

Get Instant Access to Expert-Tailored Solutions

See step-by-step solutions with expert insights and AI powered tools for academic success

Step: 2

Step: 3

Ace Your Homework with AI

Get the answers you need in no time with our AI-driven, step-by-step assistance

Get Started