Elliott Merck, senior vice-president and credit evaluator for Gift Card Capital Inc. (GCC), faced a critical decision. He had been presented with large credit requests

Elliott Merck, senior vice-president and credit evaluator for Gift Card Capital Inc. (GCC), faced a critical decision. He had been presented with large credit requests from two mid-size, multi-unit restaurant companies—Casa Grande Brands Inc. (Casa Grande) and Domingo Grill Inc. (Domingo Grill). Both companies were requesting up to US$5 million1 in cash advances, and both chains were in notable financial difficulty. In meeting with senior management from both companies, Merck could see that both organizations had taken the recessionary period as an opportunity to restructure their operations and finances; however, when looking through the financial statements for each company, he noticed that both chains had suffered significant losses in sales and had closed numerous stores. In short, neither company had been able to turn a profit for any of the past three years. Though Merck was accustomed to being a financier of last resort for many financially precarious hospitality organizations, it was unusual, even for him, to receive financing requests from such troubled companies. GCC was certainly used to taking calculated risks, but concentrating $10 million in financing into two troubled companies could either prove to be a highly lucrative investment—or the largest mistake of Merck’s career.

THE STATE OF THE RESTAURANT INDUSTRY

The restaurant industry had long been the poster child of risky businesses, with popular media often citing the dubious statistic that 90 per cent of new restaurants fail within the first year. Despite empirical evidence that restaurant failure was no more common than that of other small businesses, the perception of riskiness was the primary reason why most restaurants carried little, if any, long-term debt. No one was willing to lend to them at a reasonable rate for fear that such businesses would not exist long enough to fully repay their loans. Any risk that did exist with restaurants was typically derived from the fundamental nature of the restaurant business. Restaurants generally (1) required relatively high levels of capital expenditures with little to no resale value and high fixed operating costs, such as labour and occupancy; (2) utilized highly perishable inventory that was exposed to highly variable commodity and raw material costs; and (3) operated on negative levels of working capital.

Large chains such as Applebee’s and Outback Steakhouse successfully defrayed much of the risk associated with restaurant operations by using their size to negotiate lower food costs from purveyors; developing sophisticated real estate purchasing and site selection, and menu development models; and implementing sophisticated information technology platforms. For example, Buffalo Wild Wing’s parent company, Inspire Brands, invested $20 million in a single year to improve its speed of service and collect more detailed customer information with mobile ordering and payment systems. Similarly, Chili’s Grill & Bar parent, Brinker International, attributed its ability to weather volatility in commodity prices to a sophisticated supply chain management initiative that used technology and an entire information system team to connect suppliers with internal quality assurance, culinary, and marketing teams.6 Such costly technology investment and big-data driven initiatives helped large chains to grow larger and take market share away from smaller chains and independent restaurants.

CASA GRANDE BRANDS INC.

The Casa Grande restaurant group owned and operated full-service casual-dining establishments under three brand concepts in 29 US states. The company owned 119 Casa Grande traditional restaurants, 66 brewery restaurants, and four café restaurants, which operated under separate brand names. At its prime, Casa Grande was the seventh-largest Mexican casual-dining chain in the United States, as measured by sales. Casa Grande’s menu prices were generally positioned at the lower end of casual dining restaurants. The average spend at Casa Grande, including beverages, was about $8 for lunch and $14 for dinner.

Casa Grande restaurants ranged in size from 5,000–9,900 square feet (465–920 square metres) and accommodated up to 230 dining seats and 70 bar seats. Each restaurant was staffed with one general manager, an assistant general manager, and two to four assistant managers, depending on the restaurant’s volume. Restaurant-level managers were measured on, and rewarded for, their performance on budget and health and safety compliance, and their achievement of quality assurance goals, such as guest satisfaction, and adherence to brand standards.

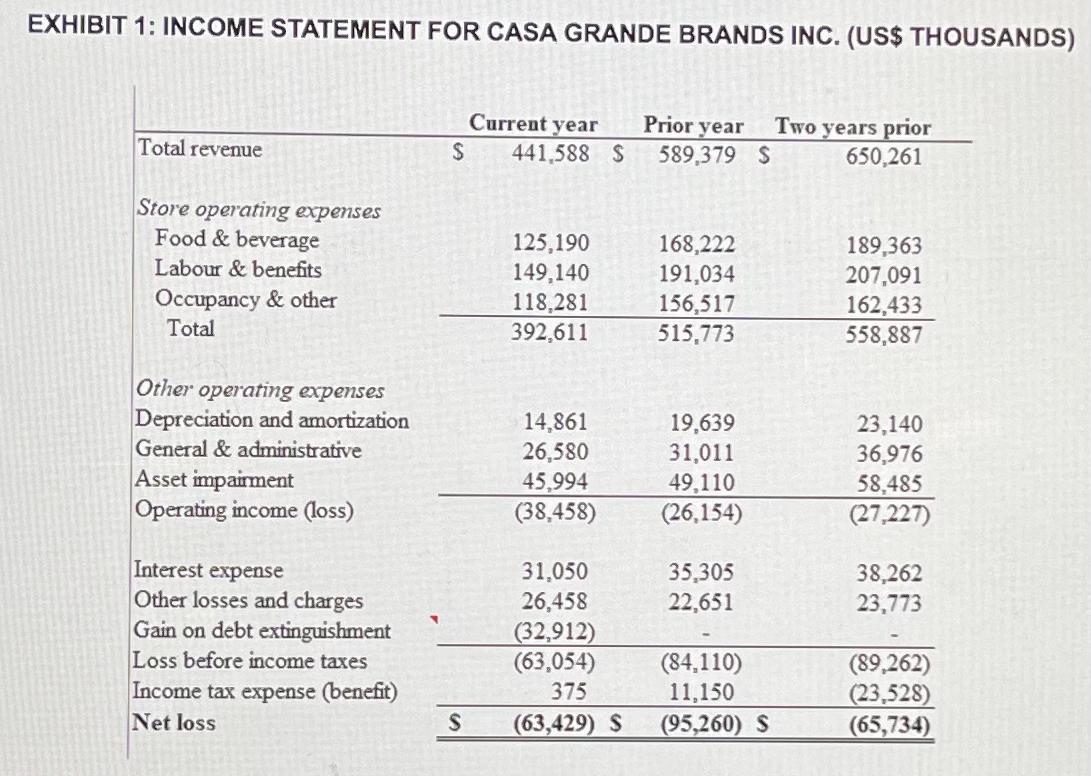

Casa Grande’s system-wide sales for the most recent year totalled $441 million, down from $589 million in the previous year, reflecting the corporate closure of underperforming stores. The average sales volume for units that had been open for at least one year was $2.1 million, which was down from the previous period. The company owned the real estate associated with 44 of its restaurants but leased either the building or the land associated with the remaining 141 sites. Management’s most recently stated focus was to reduce debt, improve liquidity, and increase profitability.

DOMINGO GRILL INC.

Domingo Grill, a Florida-based company founded in 1992, operated 70 full-service casual-dining restaurants in the United States. The company operated in 10 US states, with the overwhelming majority of operations in the Southeast. The company owned the real estate associated with 12 of its restaurants and leased the land associated with the remaining sites. The average investment in a restaurant was $1.3 million. Domingo Grill’s restaurants targeted mostly couples, families, and senior citizens. The company’s restaurants were known for their high-quality food, generous portions, diverse menus, and moderate prices. Dinner entree prices ranged from $8–$19, and lunch items were priced at $9 or less.

Domingo Grill units that had been open for more than one year generated average annual sales of $2 million. Each of Domingo Grill’s restaurants employed 60–70 people, including a general manager, kitchen manager, dining room manager, and one or two assistant managers, depending on store volume. Although much of the day-to-day operations were handled by unit-level managers, Domingo Grill centralized operational functions, such as purchasing, training, marketing, finance, and information technology.

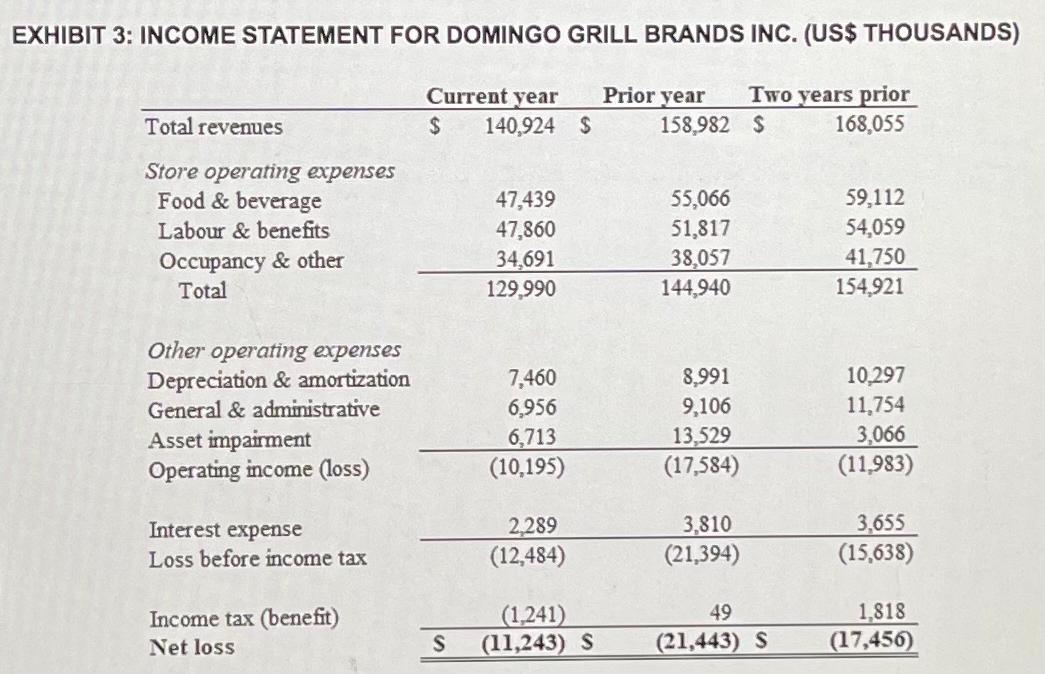

In recent years, Domingo Grill had suffered from particularly poor timing, as the company reached the peak of its expansion plans just as a recession began. In January of the most recent year, creditors demanded a financial reorganization. By the end of September of the same year, Domingo Grill received an infusion of capital from four private investors. Due to the company’s recent financial difficulties, the firm had no available lines of credit or other traditional means to raise operating capital.

THE DECISION

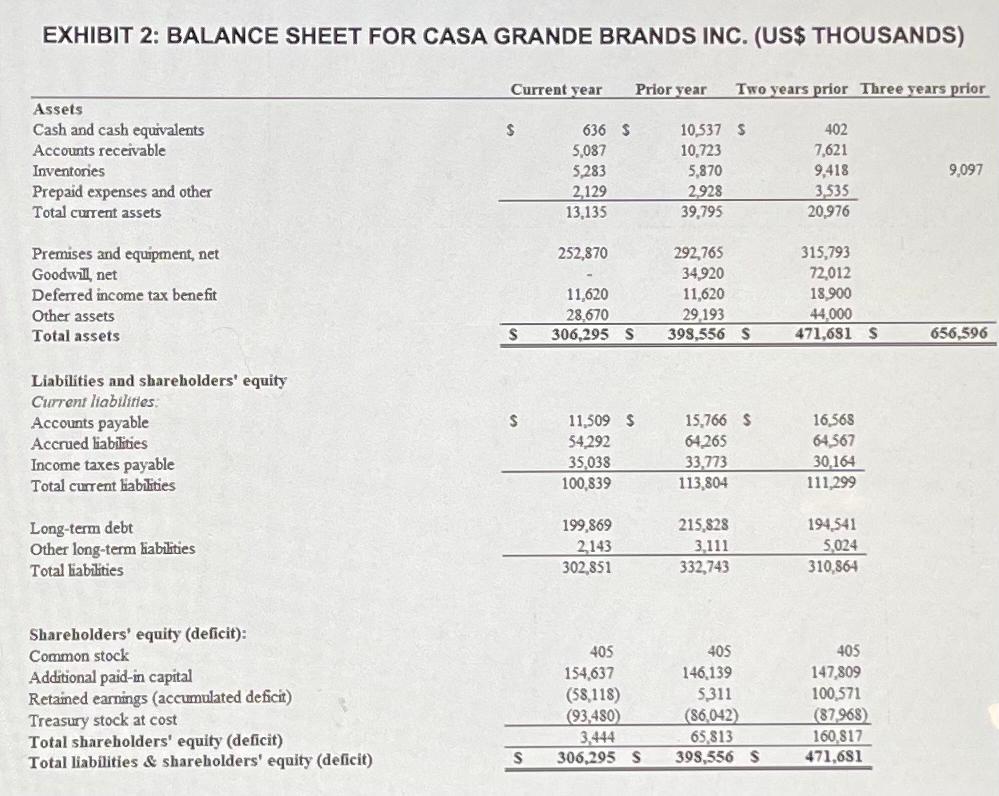

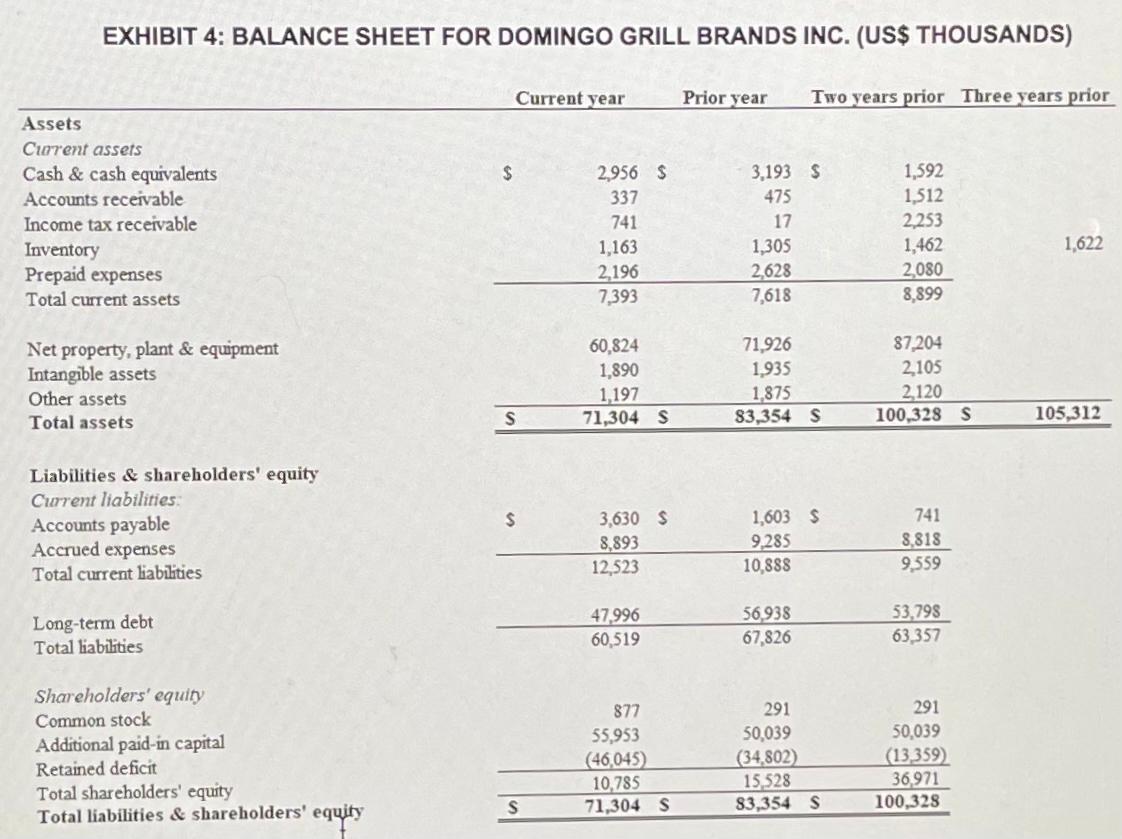

Merck looked at Casa Grande’s and Domingo Grill’s financial statements and sighed. Based on an initial look at each company’s unit-level economics, neither company looked promising. The income statements and balance sheets were not much help either, as both companies had several unusual line items that complicated Merck’s analysis. Nevertheless, he forged ahead, as he would soon need to respond to these companies’ cash requests.

REQUIRED:

In a WORD document, answer the following:

- Compare the trend of Casa Grande’s operating income before unusual charges with that of Domingo Grill. What leads to the similarity/difference between the two trends? (Maximum 150 words)

- Compare the liquidity and solvency ratios for the two firms. (Maximum 150 words)

- Compare the cash flow from operating activities and financing activities for the two firms. What key differences do you observe? (Maximum 250 words)

EXHIBIT 1: INCOME STATEMENT FOR CASA GRANDE BRANDS INC. (US$ THOUSANDS) Total revenue Store operating expenses Food & beverage Labour & benefits Occupancy & other Total Other operating expenses Depreciation and amortization General & administrative Asset impairment Operating income (loss) Interest expense Other losses and charges Gain on debt extinguishment Loss before income taxes Income tax expense (benefit) Net loss Current year $ 441,588 S 589,379 S S 125,190 149,140 118,281 392,611 14,861 26,580 45,994 (38,458) Prior year Two years prior 650,261 31,050 26,458 (32,912) (63,054) 375 (63,429) S 168,222 191,034 156,517 515,773 19,639 31,011 49,110 (26,154) 35,305 22,651 (84,110) 11,150 (95,260) S 189,363 207,091 162,433 558,887 23,140 36,976 58,485 (27,227) 38,262 23,773 (89,262) (23,528) (65,734)

Step by Step Solution

3.44 Rating (151 Votes )

There are 3 Steps involved in it

Step: 1

Compare the trend of Casa Grandes operating income before unusual charges with that of Domingo Grill What leads to the similaritydifference between the two trends Both Casa Grande and Domingo Grill ha...

See step-by-step solutions with expert insights and AI powered tools for academic success

Step: 2

Step: 3

Ace Your Homework with AI

Get the answers you need in no time with our AI-driven, step-by-step assistance

Get Started