Answered step by step

Verified Expert Solution

Question

1 Approved Answer

From 1990 to 1997, Asian countries achieved higher economic growth than any other countries. They were viewed as models for advances in technology and

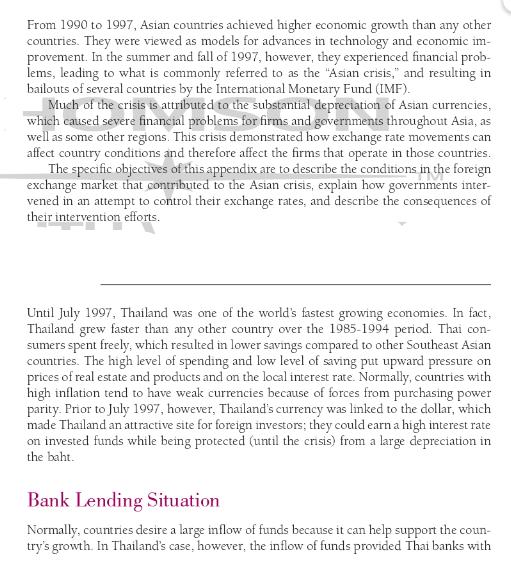

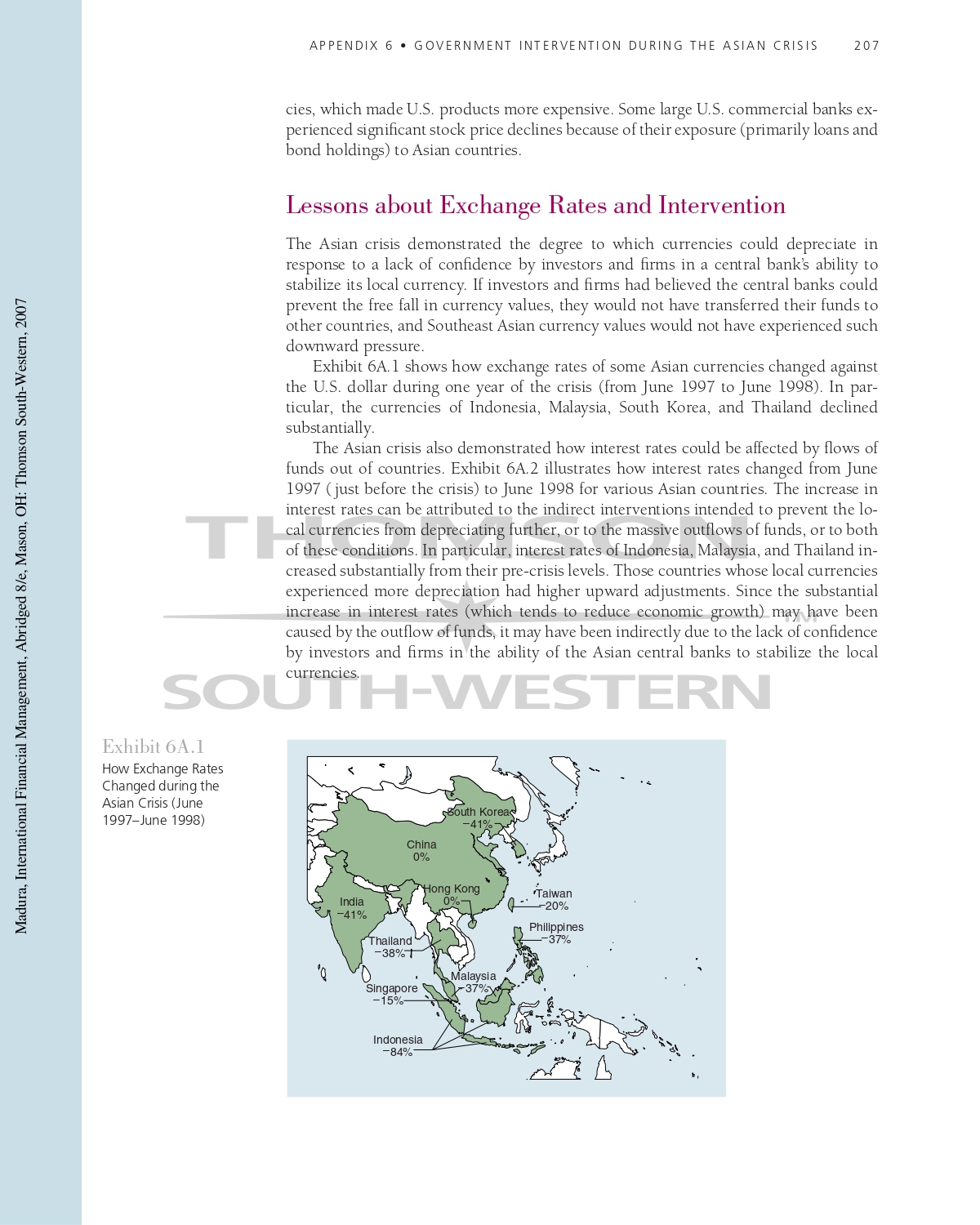

From 1990 to 1997, Asian countries achieved higher economic growth than any other countries. They were viewed as models for advances in technology and economic im- provement. In the summer and fall of 1997, however, they experienced financial prob- lems, leading to what is commonly referred to as the "Asian crisis," and resulting in bailouts of several countries by the International Monetary Fund (IMF). Much of the crisis is attributed to the substantial depreciation of Asian currencies, which caused severe financial problems for firms and governments throughout Asia, as well as some other regions. This crisis demonstrated how exchange rate movements can affect country conditions and therefore affect the firms that operate in those countries. The specific objectives of this appendix are to describe the conditions in the foreign exchange market that contributed to the Asian crisis, explain how governments inter- vened in an attempt to control their exchange rates, and describe the consequences of their intervention efforts. Until July 1997, Thailand was one of the world's fastest growing economies. In fact, Thailand grew faster than any other country over the 1985-1994 period. Thai con- sumers spent freely, which resulted in lower savings compared to other Southeast Asian countries. The high level of spending and low level of saving put upward pressure on prices of real estate and products and on the local interest rate. Normally, countries with high inflation tend to have weak currencies because of forces from purchasing power parity. Prior to July 1997, however, Thailand's currency was linked to the dollar, which made Thailand an attractive site for foreign investors; they could earn a high interest rate on invested funds while being protected (until the crisis) from a large depreciation in the baht. Bank Lending Situation Normally, countries desire a large inflow of funds because it can help support the coun- try's growth. In Thailand's case, however, the inflow of funds provided Thai banks with Madura, International Financial Management, Abridged 8/e, Mason, OH: Thomson South-Western, 2007 APPENDIX 6 GOVERNMENT INTERVENTION DURING THE ASIAN CRISIS 201 TH more funds than the banks could use for making loans. Consequently, in an attempt to use all the funds, the banks made many very risky loans. Commercial developers bor- rowed heavily without having to prove that the expansion was feasible. Lenders were willing to lend large sums of money based on the previous success of the developers. The loans may have seemed feasible based on the assumption that the economy would continue its high growth, but such high growth could not last forever. The corporate structure of Thailand also led to excessive lending. Many corporations are tied in with banks, such that some bank lending is not an "arms-length" business transaction, but a loan to a friend that needs funds. Flow of Funds Situation In addition to the lending situation, the large inflow of funds made Thailand more susceptible to a massive outflow of funds if foreign investors ever lost confidence in the Thai economy. Given the large amount of risky loans and the potential for a massive outflow of funds, Thailand was sometimes described as a "house of cards," waiting to collapse. While the large inflow of funds put downward pressure on interest rates, the sup- ply was offset by a strong demand for funds as developers and corporations sought to capitalize on the growth economy by expanding. Thailand's government was also borrowing heavily to improve the country's infrastructure. Thus, the massive borrow- ing was occurring at relatively high interest rates, making the debt expensive to the borrowers. Export Competition TM During the first half of 1997, the dollar strengthened against the Japanese yen and Eu- ropean currencies, which reduced the prices of Japanese and European imports. Al- SOthough the dollar was linked to the baht over this period, Thailand's products were not priced as competitively to U.S. importers. Pressure on the Thai Baht The baht experienced downward pressure in July 1997 as some foreign investors rec- ognized its potential weakness. The outflow of funds expedited the weakening of the baht, as foreign investors exchanged their baht for their home currencies. The baht's value relative to the dollar was pressured by the large sale of baht in exchange for dol- lars. On July 2, 1997, the baht was detached from the dollar. Thailand's central bank then attempted to maintain the baht's value by intervention. Specifically, it swapped its baht reserves for dollar reserves at other central banks and then used its dollar reserves to purchase the baht in the foreign exchange market (this swap agreement required Thailand to reverse this exchange by exchanging dollars for baht at a future date). The intervention was intended to offset the sales of baht by foreign investors in the foreign exchange market, but market forces overwhelmed the intervention efforts. As the sup- ply of baht for sale exceeded the demand for baht in the foreign exchange market, the government eventually had to surrender in its effort to defend the baht's value. In July 1997, the value of the baht plummeted. Over a five-week period, it declined by more than 20 percent against the dollar. Madura, International Financial Management, Abridged 8/e, Mason, OH: Thomson South-Western, 2007 202 PART 2 EXCHANGE RATE BEHAVIOR Damage to Thailand Thailand's central bank used more than $20 billion to purchase baht in the foreign ex- change market as part of its direct intervention efforts. Due to the decline in the value of the baht, Thailand needed more baht to be exchanged for the dollars to repay the other central banks. Thailand's banks estimated the amount of their defaulted loans at over $30 billion. Meanwhile, some corporations in Thailand had borrowed funds in other currencies (in- cluding the dollar) because the interest rates in Thailand were relatively high. This strat- egy backfired because the weakening of the baht forced these corporations to exchange larger amounts of baht for the currencies needed to pay off the loans. Consequently, the corporations incurred a much higher effective financing rate (which accounts for the ex- change rate effect to determine the true cost of borrowing) than they would have paid if they had borrowed funds locally in Thailand. The higher borrowing cost was an addi- tional strain on the corporations. Rescue Package for Thailand THon. At t On August 5, 1997, the IMF and several countries agreed to provide Thailand with a $16 billion rescue package. Japan provided $4 billion, while the IMF provided $4 bil- lion. At the time, this was the second largest bailout plan ever put together for a single country (Mexico had received a $50 billion bailout in 1994). In return for this mone- tary support, Thailand agreed to reduce its budget deficit, prevent inflation from rising above 9 percent, raise its value-added tax from 7 percent to 10 percent, and clean up the financial statements of the local banks, which had many undisclosed bad loans. The rescue package took time to finalize because Thailand's government was un- willing to shut down all the banks that were experiencing financial problems as a re- sult of their overly generous lending policies. Many critics have questioned the efficacy of the rescue package because some of the funding was misallocated due to corruption ome of the funding was misallocated in Thailand. SOL of the rescue package because some Spread of the Crisis throughout Southeast Asia The crisis in Thailand was contagious to other countries in Southeast Asia. The South- east Asian economies are somewhat integrated because of the trade between countries. The crisis was expected to weaken Thailand's economy, which would result in a reduc- tion in the demand for products produced in the other countries of Southeast Asia. As the demand for those countries' products declined, so would their national income and their demand for products from other Southeast Asian countries. Thus, the effects could perpetuate. Like Thailand, the other Southeast Asian countries had very high growth in recent years, which had led to overly optimistic assessments of future eco- nomic conditions and thus to excessive loans being extended for projects that had a high risk of default. These countries were also similar to Thailand in that they had relatively high inter- est rates, and their governments tended to stabilize their currencies. Consequently, these countries had attracted a large amount of foreign investment as well. Thailand's crisis made foreign investors realize that such a crisis could also hit the other countries in Southeast Asia. Consequently, they began to withdraw funds from these countries. Madura, International Financial Management, Abridged 8/e, Mason, OH: Thomson South-Western, 2007 APPENDIX 6 GOVERNMENT INTERVENTION DURING THE ASIAN CRISIS TH Effects on Other Asian Currencies In July and August of 1997, the values of the Malaysian ringgit, Singapore dollar, Philip- pine peso, Taiwan dollar, and Indonesian rupiah also declined. The Philippine peso was devalued in July. Malaysia initially attempted to maintain the ringgit's value within a nar- row band but then surrendered and let the ringgit float to its market-determined level. In August 1997, Bank Indonesia (the central bank) used more than $500 million in direct intervention to purchase rupiah in the foreign exchange market in an attempt to boost the value of the rupiah. By mid-August, however, it gave up its effort to maintain the rupiah's value within a band and let the rupiah float to its natural level. This deci- sion by Bank Indonesia to let the rupiah float may have been influenced by the failure of Thailand's costly efforts to maintain the baht. The market forces were too strong and could not be offset by direct intervention. On October 30, 1997, a rescue package for Indonesia was announced, but the IMF and Indonesia's government did not agree on the terms of the $43 billion package until the spring of 1998. One of the main points of con- tention was that President Suharto wanted to peg the rupiah's exchange rate, but the IMF believed that Bank Indonesia would not be able to maintain the rupiah's exchange rate at a fixed level and that it would come under renewed speculative attack. As the Southeast Asian countries gave up their fight to maintain their currencies within bands, they imposed restrictions on their forward and futures markets to prevent excessive speculation. For example, Indonesia and Malaysia imposed a limit on the size of forward contracts created by banks for foreign residents. These actions limited the de- gree to which speculators could sell these currencies forward based on expectations that the currencies would weaken over time. In general, efforts to protect the currencies failed because investors and firms had no confidence that the fundamental factors caus- ing weakness in the currencies were being corrected. Therefore, the flow of funds out of the Asian countries continued; this outflow led to even more sales of Asian currencies in exchange for other currencies, which put additional downward pressure on the val- ues of the currencies. Sources of the curr SOLs WESTERN Effects on Financing Expenses As the values of the Southeast Asian currencies declined, speculators responded by withdrawing more of their funds from these countries, which led to further weakness in the currencies. As in Thailand, many corporations had borrowed in other countries (such as the United States) where interest rates were relatively low. The decline in the values of their local currencies caused the corporations' effective rate of financing to be excessive, which strained their cash flow situation. Due to the integration of Southeast Asian economies, the excessive lending by the local banks across the countries, and the susceptibility of all these countries to massive fund outflows, the crisis was not really focused on one country. What was initially re- ferred to as the Thailand crisis became the Asian crisis. Impact of the Asian Crisis on Hong Kong On October 23, 1997, prices in the Hong Kong stock market declined by 10.2 percent on average; considering the three trading days before that, the cumulative four-day ef- fect was a decline of 23.3 percent. The decline was primarily attributed to speculation 203 Madura, International Financial Management, Abridged 8/e, Mason, OH: Thomson South-Western, 2007 204 PART 2 EXCHANGE RATE BEHAVIOR TH that Hong Kong's currency might be devalued and that Hong Kong could experience financial problems similar to the Southeast Asian countries. The fact that the market value of Hong Kong companies could decline by almost one-fourth over a four-day pe- riod demonstrated the perceived exposure of Hong Kong to the crisis. During this period, Hong Kong maintained its pegged exchange rate system with the Hong Kong dollar tied to the U.S. dollar. However, it had to increase interest rates to dis- courage investors from transferring their funds out of the country. Impact of the Asian Crisis on Russia The Asian crisis caused investors to reconsider other countries where similar effects might occur. In particular, they focused on Russia. As investors lost confidence in the Russian currency (the ruble), they began to transfer funds out of Russia. In response to the downward pressure this outflow of funds placed on the ruble, the central bank of Russia engaged in direct intervention by using dollars to purchase rubles in the foreign exchange market. It also used indirect intervention by raising interest rates to make Rus- sia more attractive to investors, thereby discouraging additional outflows. In July 1998, the IMF (with some help from Japan and the World Bank) organized a loan package worth $22.6 billion for Russia. The package required that Russia boost its tax revenue, reduce its budget deficit, and create a more capitalist environment for its businesses. During August 1998, Russia's central bank commonly intervened to prevent the ru- ble from declining substantially. On August 26, however, it gave up its fight to defend the ruble's value, and market forces caused the ruble to decline by more than 50 percent against most currencies on that day. This led to fears of a new crisis, and the next day (called "Bloody Thursday"), paranoia swept stock markets around the world. Some stock markets (including the U.S. stock market) experienced declines of more than SOUTH-WESTERN Impact of the Asian Crisis on South Korea By November 1997, seven of South Korea's conglomerates (called chaebols) had col- lapsed. The banks that financed the operations of the chaebols were stuck with the equivalent of $52 billion in bad debt as a result. Like banks in the Southeast Asian countries, South Korea's banks had been too willing to provide loans to corporations (especially the chaebols) without conducting a thorough credit analysis. The banks had apparently engaged in such risky lending because they assumed that economic growth would continue at a rapid pace and therefore exaggerated the future cash flows that bor- rowers would have available to pay off their loans. In addition, South Korean banks had traditionally extended loans to the conglomerates without assessing whether the loans could be repaid. In November, South Korea's currency (the won) declined substantially, and the central bank attempted to use its reserves to prevent a free fall in the won but with little success. Meanwhile, the credit ratings of several banks were downgraded be- cause of their bad loans. On December 3, 1997, the IMF agreed to enact a $55 billion dollar rescue package for South Korea. The World Bank and the Asian Development Bank joined with the IMF to provide a standby credit line of $35 billion. If that amount was not sufficient, other countries (including Japan and the United States) had agreed to provide a credit line of $20 billion. The total available credit (assuming it was all used) exceeded the credit pro- Madura, International Financial Management, Abridged 8/e, Mason, OH: Thomson South-Western, 2007 APPENDIX 6 GOVERNMENT INTERVENTION DURING THE ASIAN CRISIS 205 TH vided in the Mexican bailout of 1994 and made this the largest bailout ever. In exchange for the funding, South Korea agreed to reduce its economic growth and to restrict the conglomerates from excessive borrowing. This restriction resulted in some bankruptcies and unemployment, as the banks could not automatically provide loans to all conglom- erates needing funds unless the funding was economically justified. Impact of the Asian Crisis on Japan Japan was also affected by the Asian crisis because it exports products to these countries, and many of its corporations have subsidiaries in these countries so their business per- formance is affected by the local economic conditions. Japan had also been experienc- ing its own problems. Its financial industry had been struggling, primarily because of defaulted loans. In November 1997, one of Japan's 20 largest banks failed. A week later, Yamaichi Securities Co. (a brokerage firm) announced that it would shut down. Ya- maichi was the largest firm to fail in Japan since World War II. The news was shocking because the Japanese government had historically bailed out large firms such as Ya- maichi because of the possible adverse effects on other firms. Yamaichi's collapse made market participants question the potential failure of other large financial institutions that were previously perceived to be protected ("too big to fail"). The continued weakening of the Japanese yen against the dollar during the spring of 1998 put more pressure on other Asian currencies; Asian countries wanted to gain a competitive advantage in ex- porting to the United States as a result of their weak currencies. In April 1998, the Bank of Japan used more than $20 billion to purchase yen in the foreign exchange market. This effort to boost the yen's value was unsuccessful. In July 1998, Prime Minister Hashimoto resigned, causing more uncertainty about the outlook for Japan. Impact of the Asian Crisis on China SOL Ironically: China did not the adverse economic effects of the Ironically, China did not experience the adverse economic effects of the Asian crisis be- cause it had grown less rapidly than the Southeast Asian countries in the years prior to the crisis. The Chinese government had more control over economic conditions because it still owned most real estate and still controlled most of the banks that provided credit to support growth. Thus, there were fewer bankruptcies resulting from the crisis in China. In addition, China's government was able to maintain the value of the yuan against the dollar, which limited speculative flows of funds out of China. Though inter- est rates increased during the crisis, they remained relatively low. Consequently Chinese firms could obtain funding at a reasonable cost and could continue to meet their inter- est payments. Nevertheless, concerns about China mounted because it relies heavily on exports to stimulate its economy; China was now at a competitive disadvantage relative to the Southeast Asian countries whose currencies had depreciated. Thus, importers from the United States and Europe shifted some of their purchases to those countries. In addi- tion, the decline in the other Asian currencies against the Chinese yuan encouraged Chi- nese consumers to purchase imports instead of locally manufactured products. Impact of the Asian Crisis on Latin American Countries The Asian crisis also affected Latin American countries. Countries such as Chile, Mex- ico, and Venezuela were adversely affected because they export products to Asia, and the Madura, International Financial Management, Abridged 8/e, Mason, OH: Thomson South-Western, 2007 206 PART 2 EXCHANGE RATE BEHAVIOR weak Asian economies resulted in a lower demand for the Latin American exports. In addition, the Latin American countries lost some business to other countries that switched to Asian products because of the substantial depreciation of the Asian curren- cies, which made their products cheaper than those of Latin America. The adverse effects on Latin American countries put pressure on Latin American currency values, as there was concern that speculative outflows of funds would weaken these currencies in the same way that Asian currencies had weakened. In particular, there was pressure on Brazil's currency (the real) in late October 1997. Some specula- tors believed that since most Asian countries could not maintain their currencies within bands under the existing conditions, Brazil would be unable to stabilize the value of its currency. The central bank of Brazil used about $7 billion of reserves in a direct intervention to buy the real in the foreign exchange market and protect the real from depreciation. It also used indirect intervention by raising short-term interest rates in Brazil. This en- couraged foreign investment in Brazil's short-term securities to capitalize on the high in- terest rates and also encouraged local investors to invest locally rather than in foreign markets. The adjustment of interest rates to maintain the value of the real signaled that the central bank of Brazil was serious about maintaining the currency's stability. The in- tervention was costly, however, because it increased the cost of borrowing for house- holds, corporations, and government agencies in Brazil and thus could reduce economic growth. If Brazil's currency had weakened, the speculative forces might have spread to the other Latin American currencies as well. The Asian crisis also caused bond ratings of many large corporations and govern- ment agencies in Latin America to be downgraded. Rumors that banks were dumping Asian bonds caused fears that all emerging market debt would be dumped in the bond markets. Furthermore, there was concern that many banks experiencing financial prob- lems (because their loans were not being paid back) would sell bond holdings in the secondary market in order to raise funds. Consequently, prices of bonds issued in emerging markets declined, including those of Latin American countries. SOLemerging markets deel Impact of the Asian Crisis on Europe During the Asian crisis, European countries were experiencing strong economic growth. Many European firms, however, were adversely affected by the crisis. Like firms in Latin America, some firms in Europe experienced a reduced demand for their exports to Asia during the crisis. In addition, they lost some exporting business to Asian exporters as a result of the weakened Asian currencies that reduced Asian prices from an importer's perspective. European banks were especially affected by the Asian crisis because they had provided large loans to numerous Asian firms that defaulted. Impact of the Asian Crisis on the United States The effects of the Asian crisis were even felt in the United States. Stock values of U.S. firms, such as 3M Co., Motorola, Hewlett-Packard, and Nike, that conducted much business in Asia declined. Many U.S. engineering and construction firms were adversely affected as Asian countries reduced their plans to improve infrastructure. Stock values of U.S. exporters to those countries fell because of the decline in spending by consumers and corporations in Asian countries and because of the weakening of the Asian curren- Madura, International Financial Management, Abridged 8/e, Mason, OH: Thomson South-Western, 2007 APPENDIX 6 GOVERNMENT INTERVENTION DURING THE ASIAN CRISIS 207 TH cies, which made U.S. products more expensive. Some large U.S. commercial banks ex- perienced significant stock price declines because of their exposure (primarily loans and bond holdings) to Asian countries. Lessons about Exchange Rates and Intervention The Asian crisis demonstrated the degree to which currencies could depreciate in response to a lack of confidence by investors and firms in a central bank's ability to stabilize its local currency. If investors and firms had believed the central banks could prevent the free fall in currency values, they would not have transferred their funds to other countries, and Southeast Asian currency values would not have experienced such downward pressure. Exhibit 6A.1 shows how exchange rates of some Asian currencies changed against the U.S. dollar during one year of the crisis (from June 1997 to June 1998). In par- ticular, the currencies of Indonesia, Malaysia, South Korea, and Thailand declined substantially. The Asian crisis also demonstrated how interest rates could be affected by flows of funds out of countries. Exhibit 6A.2 illustrates how interest rates changed from June 1997 (just before the crisis) to June 1998 for various Asian countries. The increase in interest rates can be attributed to the indirect interventions intended to prevent the lo- cal currencies from depreciating further, or to the massive outflows of funds, or to both of these conditions. In particular, interest rates of Indonesia, Malaysia, and Thailand in- creased substantially from their pre-crisis levels. Those countries whose local currencies experienced more depreciation had higher upward adjustments. Since the substantial increase in interest rates (which tends to reduce economic growth) may have been caused by the outflow of funds, it may have been indirectly due to the lack of confidence by investors and firms in the ability of the Asian central banks to stabilize the local SOUTH-WESTERN Exhibit 6A.1 How Exchange Rates Changed during the Asian Crisis (June 1997-June 1998) China 0% South Korea -41%- India -41% Hong Kong 0%- Taiwan -20% Thailand -38% Philippines -37% Singapore -15% Malaysia -37% Indonesia -84% Madura, International Financial Management, Abridged 8/e, Mason, OH: Thomson South-Western, 2007 208 PART 2 EXCHANGE RATE BEHAVIOR Exhibit 6A.2 How Interest Rates Changed during the Asian Crisis (Number before slash represents annualized interest rate as of June 1997; number after slash represents annualized interest rate as of June 1998) China 8/7 South Kore 14/17 India 12/7 Hong Kong 6/10 Talwan -5/7 Philippines Thailand 11/24 11/14 Singapore 3/7 Malaysia 7/11- Indonesia 16/47 Finally, the Asian crisis demonstrated how integrated country economies are, espe- cially during a crisis. Just as the U.S. and European economies can affect emerging mar- kets, they are susceptible to conditions in emerging markets. Even if a central bank can withstand the pressure on its currency caused by conditions in other countries, it can- not necessarily insulate its economy from other countries that are experiencing financial problems. DISCUSSION QUESTIONS The following discussion questions related to the Asian cri- sis illustrate how the foreign exchange market conditions are integrated with the other financial markets around the world. Thus, participants in any of these markets must un- derstand the dynamics of the foreign exchange market. These discussion questions can be used in several ways. They may serve as an assignment on a day that the profes- sor is unable to attend class. They are especially useful for group exercises. The class could be segmented into small groups; each group is asked to assess all of the issues and de- termine a solution. Each group should have a spokesperson. For each issue, one of the groups will be randomly selected and asked to present their solution, and then other students not in that group may suggest alternative answers if they feel that the answer can be improved. Some of the issues have no perfect solution, which allows for different points of view to be presented by students. TM 1. Was the depreciation of the Asian currencies dur- ing the Asian crisis due to trade flows or capital flows? Why do you think the degree of movement over a short period may depend on whether the rea- son is trade flows or capital flows? 2. Why do you think the Indonesian rupiah was more exposed to an abrupt decline in value than the Jap- anese yen during the Asian crisis (even if their econ- omies experienced the same degree of weakness)? 3. During the Asian crisis, direct intervention did not prevent depreciation of currencies. Offer your ex- planation for why the interventions did not work. 4. During the Asian crisis, some local firms in Asia borrowed dollars rather than local currency to sup- port local operations. Why would they borrow dol- Madura, International Financial Management, Abridged 8/e, Mason, OH: Thomson South-Western, 2007 APPENDIX 6 GOVERNMENT INTERVENTION DURING THE ASIAN CRISIS 209 lars when they really needed their local currency to support operations? Why did this strategy backfire? 5. The Asian crisis showed that a currency crisis could affect interest rates. Why did the crisis put upward pressure on interest rates in Asian countries? Why did it put downward pressure on U.S. interest rates? 6. According to the international Fisher effect, high in- terest rates reflect high expected inflation, and can signal future weakness in a currency. Based on this theory, how would expectations of Asian exchange rates change after interest rates in Asia increased? Why? Is the underlying reason logical? 7. During the Asian crisis, why did the discount of the forward rate of Asian currencies change? Do you think it increased or decreased? Why? 8. During the Hong Kong crisis, the Hong Kong stock market declined substantially over a four-day pe- riod due to concerns in the foreign exchange market. Why would stock prices decline due to exchange concerns the foreign market? Why would some countries be more susceptible to this type of situation than others? 9. On August 26, 1998, the day that Russia decided to let the ruble float freely, the ruble declined by about 50 percent. On the following day, called "Bloody Thursday," stock markets around the the weak currencies of Asia adversely affected their economies. Why do you think the weakening of the currencies did not initially improve their econo- mies during the Asian crisis? 11. During the Asian crisis, Hong Kong and China suc- cessfully intervened (by raising their interest rates) to protect their local currencies from depreciating. Nevertheless, these countries were also adversely affected by the Asian crisis. Why do you think the actions to protect the values of their currencies af- fected these countries' economies? Why do you think the weakness of other Asian currencies against the dollar and the stability of the Chinese and Hong Kong currencies against the dollar ad- versely affected their economies? 12. Why do you think the values of bonds issued by Asian governments declined during the Asian cri- sis? Why do you think the values of Latin American bonds declined in response to the Asian crisis? 13. Why do you think the depreciation of the Asian currencies adversely affected U.S. firms? (There are at least three reasons, each related to a different type of exposure of some U.S. firms to exchange rate risk.) TM 14. During the Asian crisis, the currencies of many Asian countries declined even though their govern- intervene with direct interven- world (including the United States) declined by men or by raising interest rates. Given that the more than 4 percent. Why do you think the decline in the ruble had such a global impact on stock prices? Was the markets' reaction rational? Would the effect have been different if the ruble's plunge had occurred in an earlier time period, such as four years earlier? Why? 10. Normally, a weak local currency is expected to stimulate the local economy. Yet, it appeared that abrupt depreciation of the currencies was attrib- uted to an abrupt outflow of funds in the financial markets, what alternative Asian government action might have been more successful in preventing a substantial decline in the currencies' values? Are there any possible adverse effects of your proposed solution?

Step by Step Solution

There are 3 Steps involved in it

Step: 1

Get Instant Access to Expert-Tailored Solutions

See step-by-step solutions with expert insights and AI powered tools for academic success

Step: 2

Step: 3

Ace Your Homework with AI

Get the answers you need in no time with our AI-driven, step-by-step assistance

Get Started