Hello, Could you please answer this question?

Thank you very much.

* If prospective students could no longer use government programs to finance their studies, what implications would this have for the University of Waterloo's business model?

How would the change affect the risk profile of the incoming students?

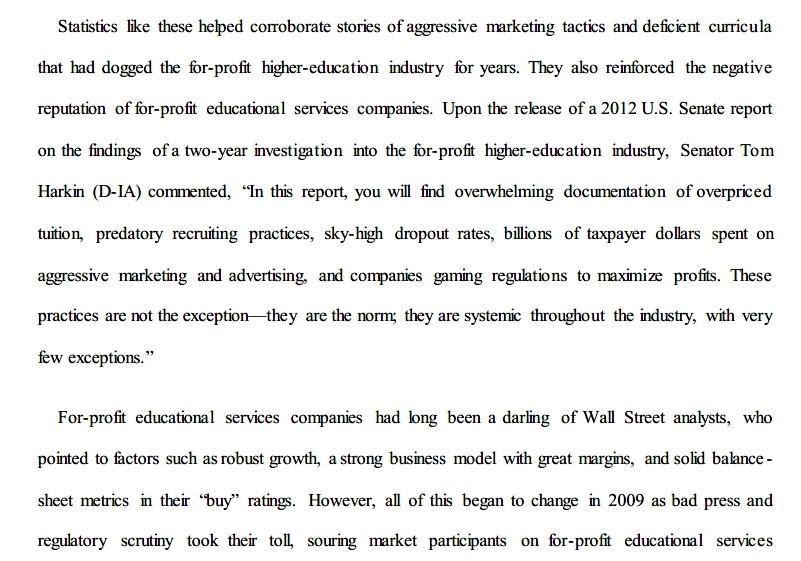

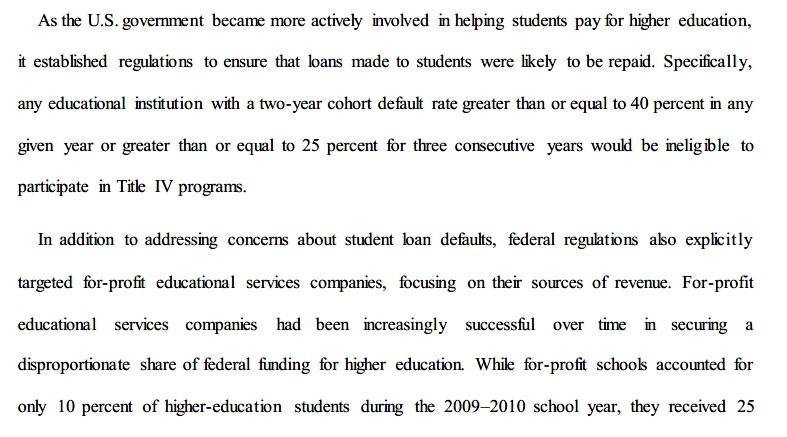

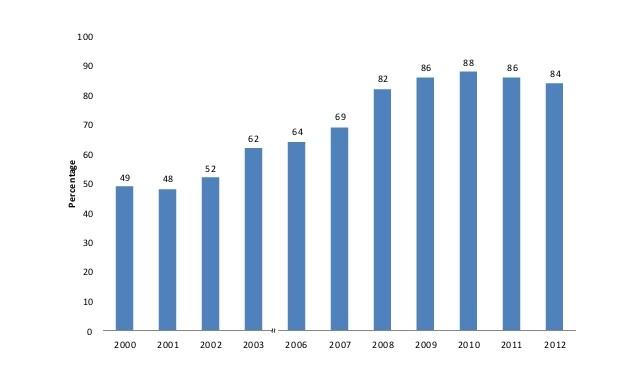

(Exhibit 2): FY 2000 - 2012 University of Waterloo Percentage of Cash Basis Revenue from Title IV

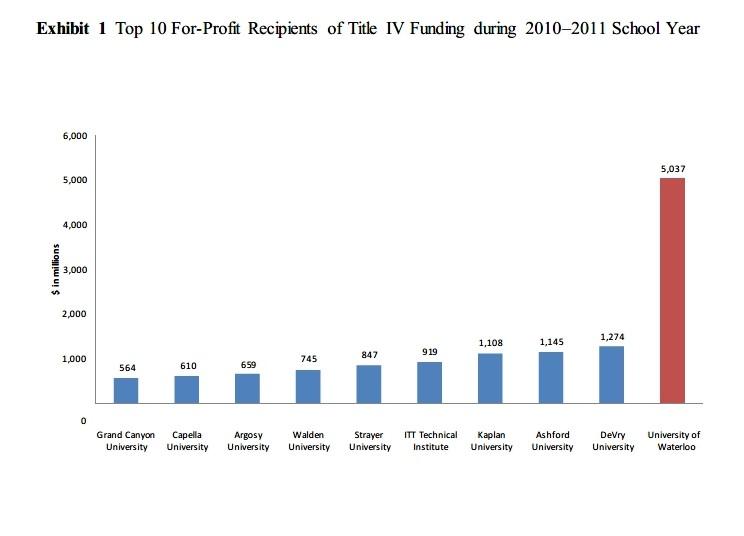

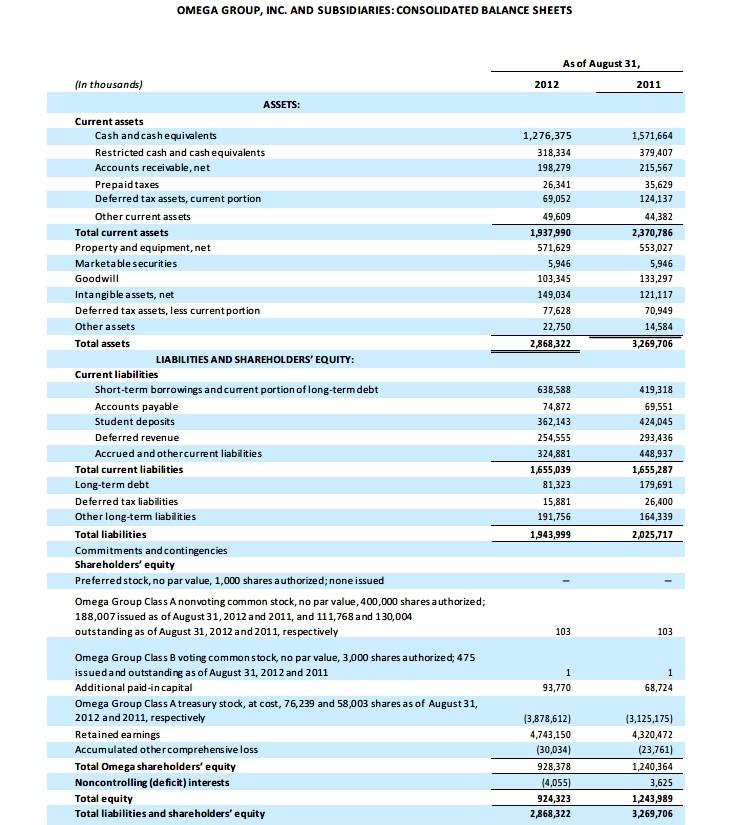

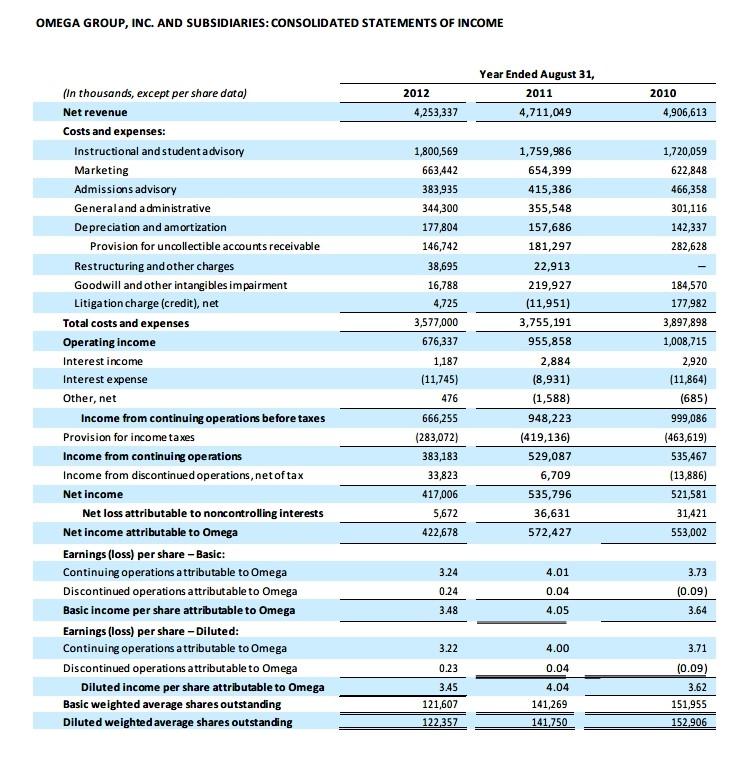

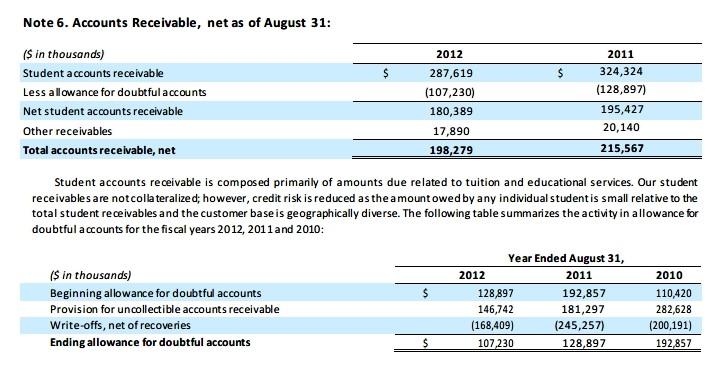

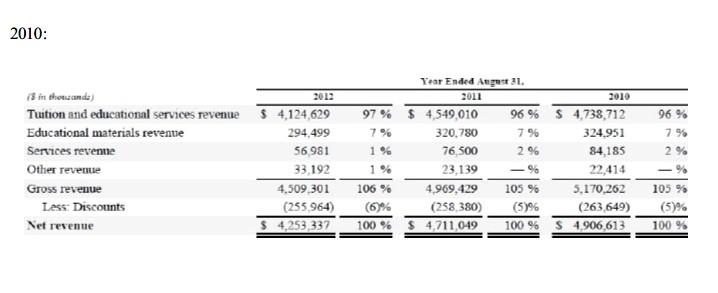

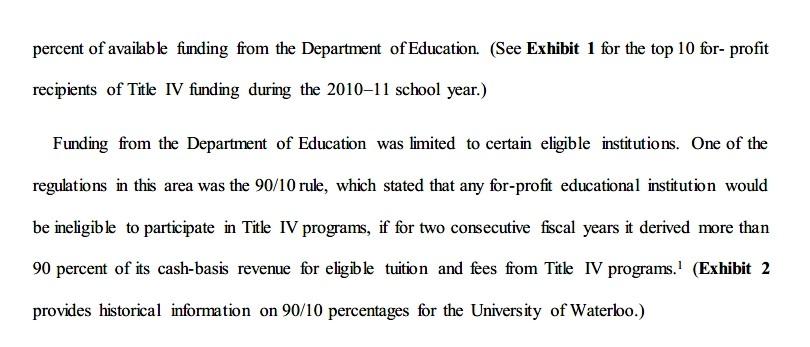

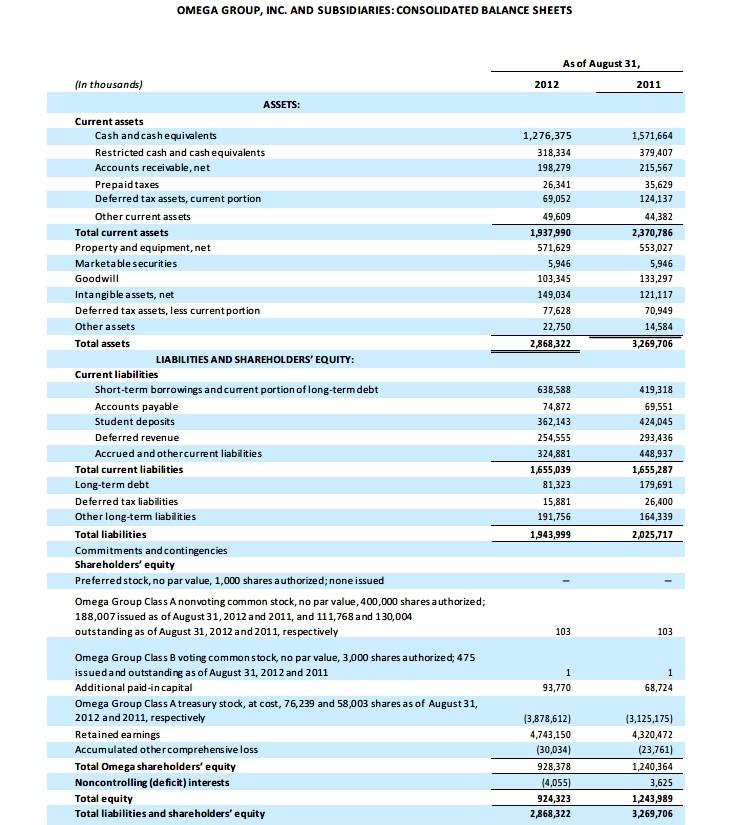

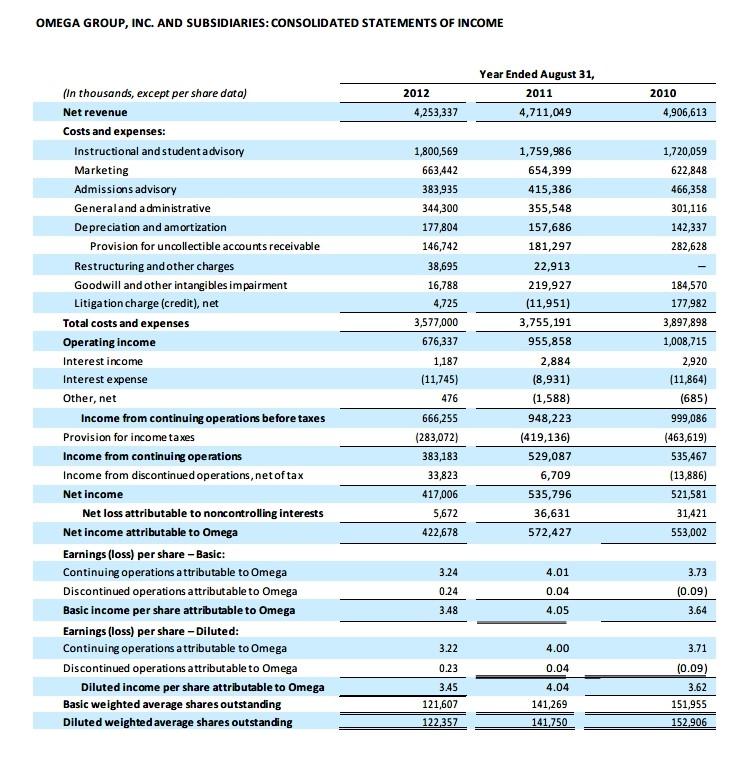

(Exhibit 3) : FY 2012 Omega Group Balance Sheet and Income Statement

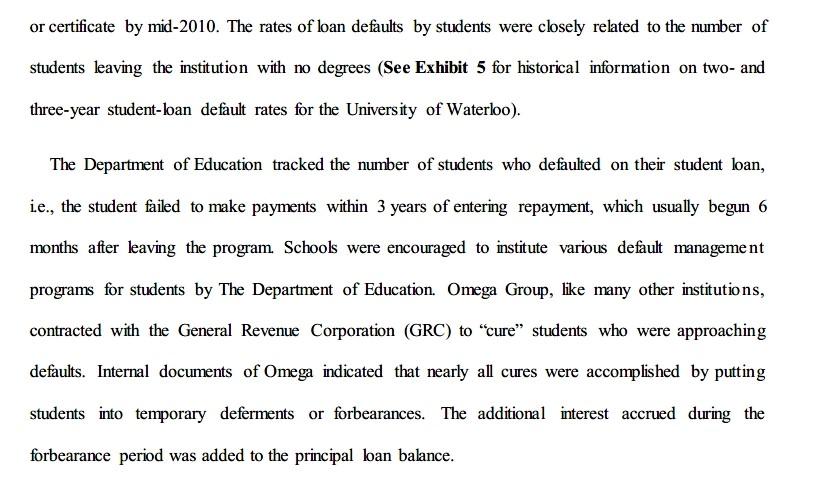

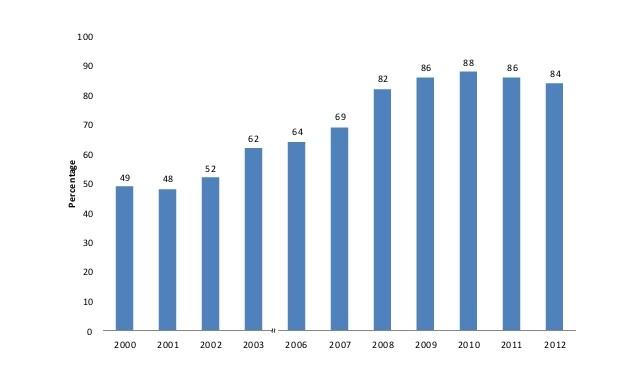

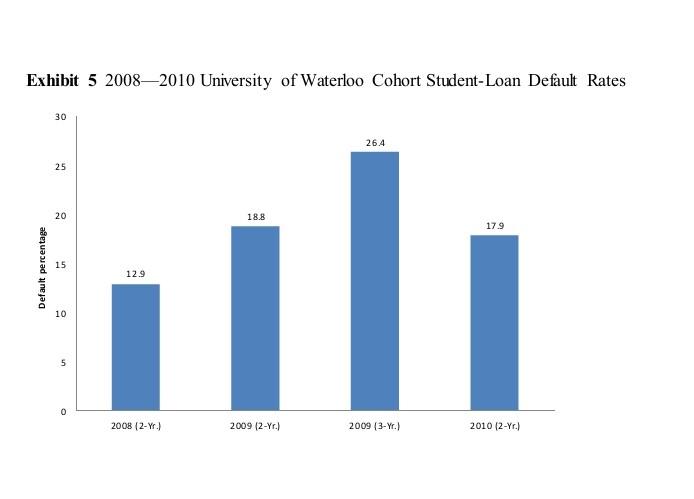

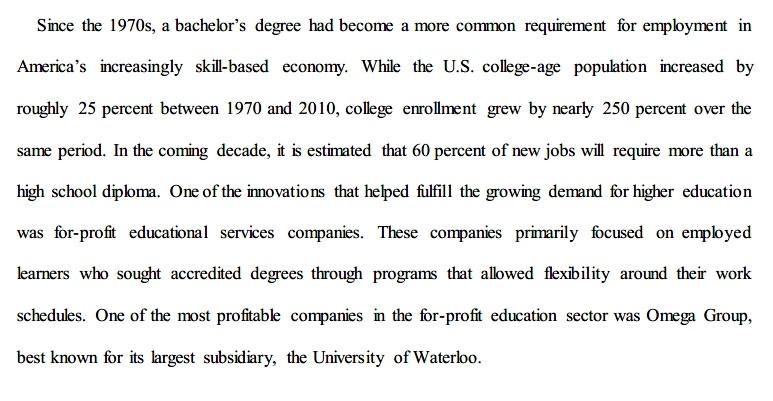

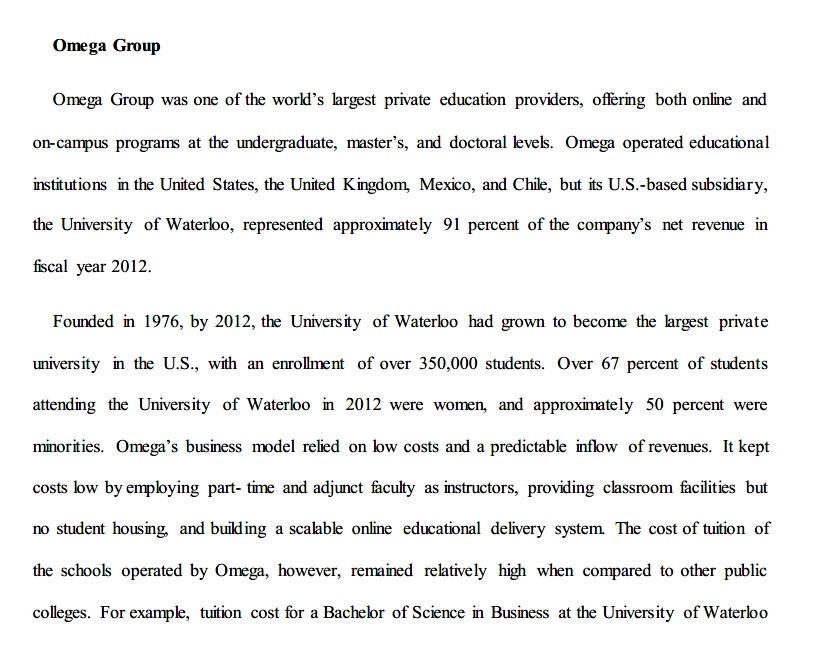

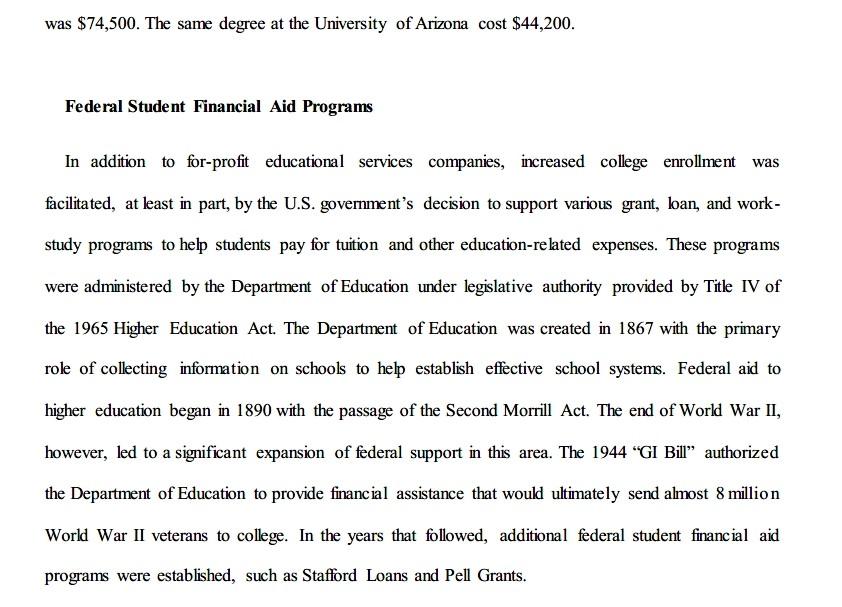

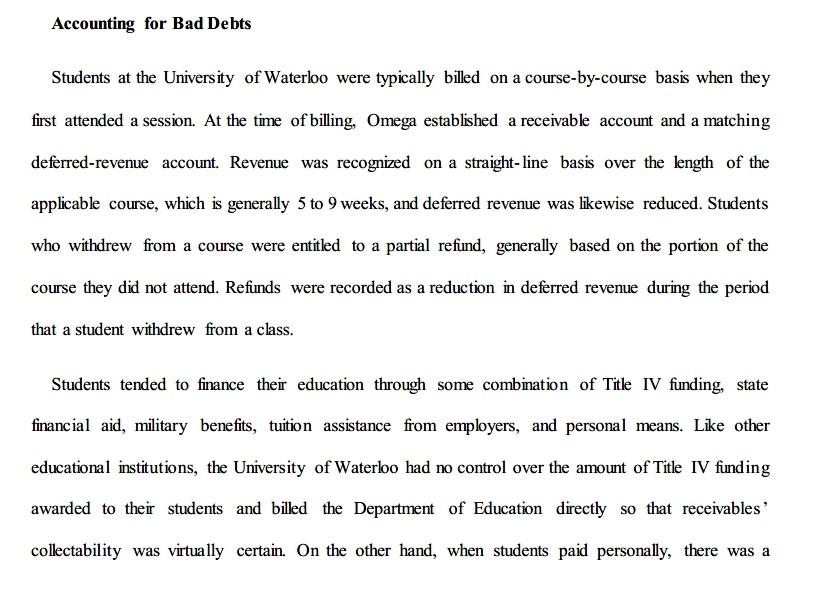

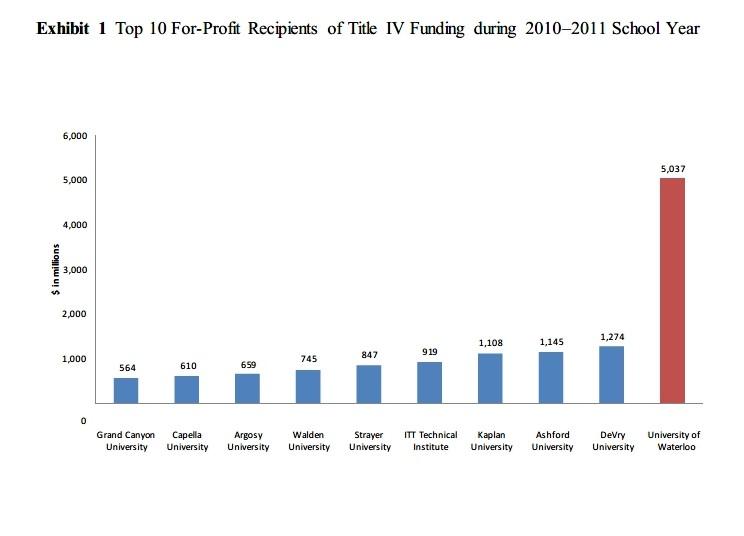

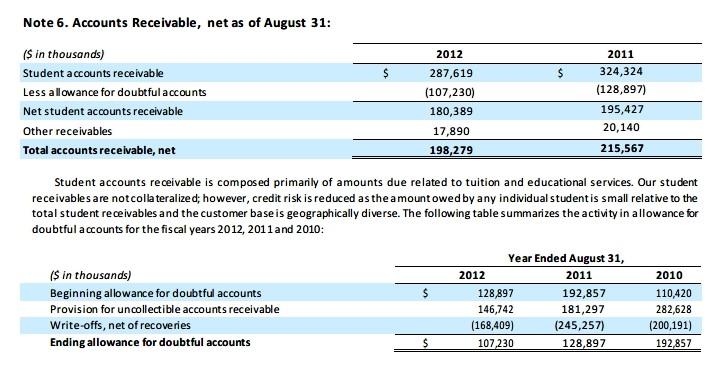

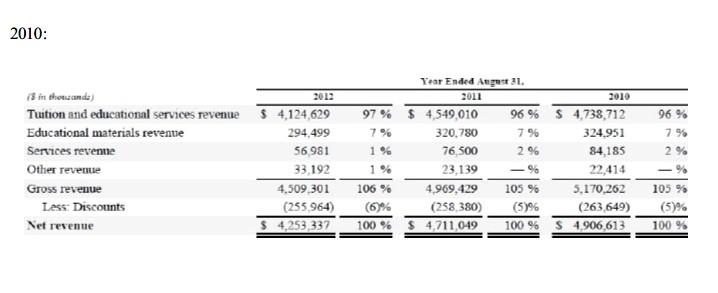

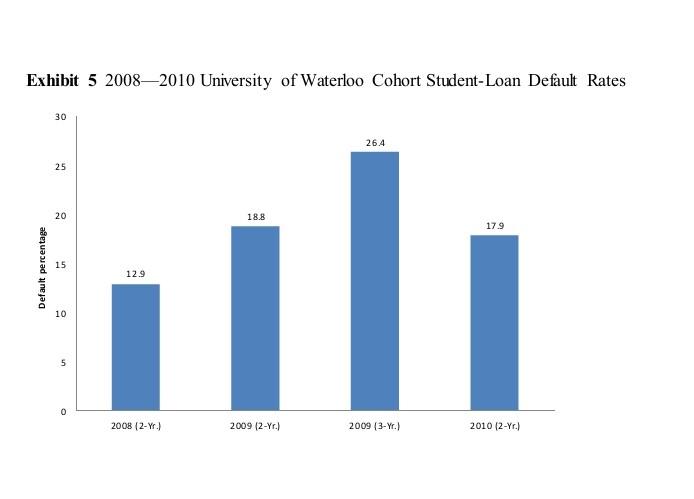

Since the 1970s, a bachelor's degree had become a more common requirement for employment in America's increasingly skill-based economy. While the U.S. college-age population increased by roughly 25 percent between 1970 and 2010, college enrollment grew by nearly 250 percent over the same period. In the coming decade, it is estimated that 60 percent of new jobs will require more than a high school diploma. One of the innovations that helped fulfill the growing demand for higher education was for-profit educational services companies. These companies primarily focused on employed learners who sought accredited degrees through programs that allowed flexibility around their work schedules. One of the most profitable companies in the for-profit education sector was Omega Group, best known for its largest subsidiary, the University of Waterloo. Omega Group Omega Group was one of the world's largest private education providers, offering both online and on-campus programs at the undergraduate, master's, and doctoral levels. Omega operated educational institutions in the United States, the United Kingdom, Mexico, and Chile, but its U.S.-based subsidiary, the University of Waterloo, represented approximately 91 percent of the company's net revenue in fiscal year 2012. Founded in 1976, by 2012, the University of Waterloo had grown to become the largest private university in the U.S., with an enrollment of over 350,000 students. Over 67 percent of students attending the University of Waterloo in 2012 were women, and approximately 50 percent were minorities. Omega's business model relied on low costs and a predictable inflow of revenues. It kept costs low by employing part-time and adjunct faculty as instructors, providing classroom facilities but no student housing and build ing a scalable online educational delivery system. The cost of tuition of the schools operated by Omega, however, remained relatively high when compared to other public colleges. For example, tuition cost for a Bachelor of Science in Business at the University of Waterloo was $74,500. The same degree at the University of Arizona cost $44,200. Federal Student Financial Aid Programs In addition to for-profit educational services companies, increased college enrollment was facilitated, at least in part, by the U.S. government's decision to support various grant, loan, and work- study programs to help students pay for tuition and other education-related expenses. These programs were administered by the Department of Education under legislative authority provided by Title IV of the 1965 Higher Education Act. The Department of Education was created in 1867 with the primary role of collecting information on schools to help establish effective school systems. Federal aid to higher education began in 1890 with the passage of the Second Morrill Act. The end of World War II, however, led to a significant expansion of federal support in this area. The 1944 GI Bill" authorized the Department of Education to provide financial assistance that would ultimately send almost 8 million World War II veterans to college. In the years that followed, additional federal student financial aid programs were established, such as Stafford Loans and Pell Grants. As the U.S. government became more actively involved in helping students pay for higher education, it established regulations to ensure that loans made to students were likely to be repaid. Specifically, any educational institution with a two-year cohort default rate greater than or equal to 40 percent in any given year or greater than or equal to 25 percent for three consecutive years would be ineligible to participate in Title IV programs. In addition to addressing concerns about student loan defaults, federal regulations also explicitly targeted for-profit educational services companies, focusing on their sources of revenue. For-profit educational services companies had been increasingly successful over time in securing a disproportionate share of federal funding for higher education. While for-profit schools accounted for only 10 percent of higher-education students during the 20092010 school year, they received 25 percent of available funding from the Department of Education. (See Exhibit 1 for the top 10 for-profit recipients of Title IV funding during the 2010-11 school year.) Funding from the Department of Education was limited to certain eligible institutions. One of the regulations in this area was the 90/10 rule, which stated that any for-profit educational institution would be ineligible to participate in Title IV programs, if for two consecutive fiscal years it derived more than 90 percent of its cash-basis revenue for eligible tuition and fees from Title IV programs. (Exhibit 2 provides historical information on 90/10 percentages for the University of Waterloo.) Accounting for Bad Debts Students at the University of Waterloo were typically billed on a course-by-course basis when they first attended a session. At the time of billing, Omega established a receivable account and a matching deferred-revenue account. Revenue was recognized on a straight-line basis over the length of the applicable course, which is generally 5 to 9 weeks, and deferred revenue was likewise reduced. Students who withdrew from a course were entitled to a partial refund, generally based on the portion of the course they did not attend. Refunds were recorded as a reduction in deferred revenue during the period that a student withdrew from a class. Students tended to finance their education through some combination of Title IV funding, state financial aid, military benefits, tuition assistance from employers, and personal means. Like other educational institutions, the University of Waterloo had no control over the amount of Title IV funding awarded to their students and billed the Department of Education directly so that receivables' collectability was virtually certain. On the other hand, when students paid personally, there was a possibility that receivables would not be collectible. To account for the issue of uncollectible receivables, Omega reduced its receivables, as they were generated, by setting up allowances for amounts expected to become uncollectible. These estimates were based on historical collection experience, current trends, and other relevant factors. For example, the company increased its allowance for doubtful accounts after a student withdrew from an educational program. When an actual write-off occurred, the receivable was removed from the balance sheet, and the allowance for doubtful accounts was correspondingly decreased. (See Exhibit 3 for Omega's fiscal year 2012 balance sheet and income statement, and Exhibit 4 for historical information on Omega revenues, receivables, allowances for receivables expected to become uncollectible, provisions incurred in different periods for potentially uncollectible receivables, and write-offs as they took place.) Signs of Trouble In the wake of the 20072009 financial crisis, many began to question the value of higher education. Skyrocketing tuition had grown by almost five times the rate of inflation since 1983 and had resulted in students taking on ever more debt. Toward the end of 2012, student-loan debt in the U.S. approached $1 trillion dollars. At the same time, diminished job prospects due to relatively weak economic conditions caused student-loan delinquencies to rise, with student loans accounting for a higher percentage of household debt over 90 days past due than credit cards, mortgages, auto loans, and home-equity loans. While many blamed the financial crisis for high student-loan default rates, others pointed to another culprit: for-profit higher education. Differences in student outcomes had emerged between for-profit and not-for-profit schools. The three-year student-loan default rate for the 20082009 cohort of students was 8 percent at private not- for-profit schools and 11 percent at public not-for-profit schools, but it was 23 percent at for-profit schools. Of students who enrolled in for-profit schools in 2008-2009, 54 percent left without a degree or certificate by mid-2010. The rates of loan defaults by students were closely related to the number of students leaving the institution with no degrees (See Exhibit 5 for historical information on two- and three-year student-loan default rates for the University of Waterloo). The Department of Education tracked the number of students who defaulted on their student loan, ie., the student failed to make payments within 3 years of entering repayment, which usually begun 6 months after leaving the program Schools were encouraged to institute various default management programs for students by The Department of Education. Omega Group, like many other institutions, contracted with the General Revenue Corporation (GRC) to "cure students who were approaching defaults. Internal documents of Omega indicated that nearly all cures were accomplished by putting students into temporary deferments or forbearances. The additional interest accrued during the forbearance period was added to the principal loan balance. Statistics like these helped corroborate stories of aggressive marketing tactics and deficient curricula that had dogged the for-profit higher-education industry for years. They also reinforced the negative reputation of for-profit educational services companies. Upon the release of a 2012 U.S. Senate report on the findings of a two-year investigation into the for-profit higher-education industry, Senator Tom Harkin (D-IA) commented, In this report, you will find overwhelming documentation of overpriced tuition, predatory recruiting practices, sky-high dropout rates, billions of taxpayer dollars spent on aggressive marketing and advertising, and companies gaming regulations to maximize profits. These practices are not the exceptionthey are the norm; they are systemic throughout the industry, with very few exceptions." For-profit educational services companies had long been a darling of Wall Street analysts, who pointed to factors such as robust growth, a strong business model with great margins, and solid balance - sheet metrics in their buy ratings. However, all of this began to change in 2009 as bad press and regulatory scrutiny took their toll, souring market participants on for-profit educational services Exhibit 1 Top 10 For-Profit Recipients of Title IV Funding during 20102011 School Year 6,000 5,037 5,000 4,000 $ in millions 3,000 2,000 1,274 1,108 1,145 847 919 1,000 745 564 610 659 0 Grand Canyon University Capella University Argosy University Walden University Strayer University ITT Technical Institute Kaplan University Ashford University Devry University University of Waterloo 100 90 88 86 86 82 84 80 69 70 64 62 60 52 49 48 Percentage 50 40 30 20 10 0 2000 2001 2002 2003 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 OMEGA GROUP, INC. AND SUBSIDIARIES: CONSOLIDATED BALANCE SHEETS As of August 31, 2012 2011 1,276,375 318,334 198,279 26,341 69,052 49,609 1,937,990 571,629 5,946 103,345 149,034 77,628 22,750 2,868,322 1,571,664 379,407 215,567 35,629 124,137 44,382 2,370,786 553,027 5,946 133,297 121,117 70,949 14,584 3,269,706 419,318 (in thousands) ASSETS: Current assets Cash and cash equivalents Restricted cash and cash equivalents Accounts receivable, net Prepaid taxes Deferred tax assets, current portion Other current assets Total current assets Property and equipment, net Marketable securities Goodwill Intangible assets, net Deferred tax assets, less current portion Other assets Total assets LIABILITIES AND SHAREHOLDERS' EQUITY: Current liabilities Short-term borrowings and current portion of long-term debt Accounts payable Student deposits Deferred revenue Accrued and other current liabilities Total current liabilities Long-term debt Deferred tax liabilities Other long-term liabilities Total liabilities Commitments and contingencies Shareholders' equity Preferred stock, no par value, 1,000 shares authorized; none issued Omega Group Class A nonvoting common stock, no par value,400,000 shares authorized; 188,007 issued as of August 31, 2012 and 2011, and 111,768 and 130,004 outstanding as of August 31, 2012 and 2011, respectively Omega Group Class B voting common stock, no par value, 3,000 shares authorized: 475 issued and outstanding as of August 31, 2012 and 2011 Additional paid-in capital Omega Group Class A treasury stock, at cost, 76,239 and 58,003 shares as of August 31, 2012 and 2011, respectively Retained earnings Accumulated other comprehensive loss Total Omegashareholders' equity Noncontrolling (deficit) interests Total equity Total liabilities and shareholders' equity 638,588 74,872 362,143 254,555 324,881 1,655,039 81,323 15,881 191,756 1,943,999 69,551 424,045 293,436 448,937 1,655,287 179,691 26,400 164,339 2,025,717 103 103 1 93,770 1 68,724 13,878,612) 4,743,150 (30,034) 928,378 (4,055) 924,323 2,868,322 (3,125,175) 4,320,472 (23,761) 1,240,364 3,625 1,243,989 3,269,706 OMEGA GROUP, INC. AND SUBSIDIARIES: CONSOLIDATED STATEMENTS OF INCOME 2012 4,253,337 Year Ended August 31, 2011 4,711,049 2010 4,906,613 1,759,986 1,720,059 622,848 466,358 301,116 142,337 282,628 1,800,569 663,442 383,935 344,300 177,804 146,742 38,695 16,788 4,725 3,577,000 676,337 1,187 (11,745) 476 (In thousands, except per share data) Net revenue Costs and expenses: Instructional and studentadvisory Marketing Admissions advisory General and administrative Depreciation and amortization Provision for uncollectible accounts receivable Restructuring and other charges Goodwill and other intangibles impairment Litigation charge (credit), net Total costs and expenses Operating income Interest income Interest expense Other, net Income from continuing operations before taxes Provision for income taxes Income from continuing operations Income from discontinued operations, net of tax Net income Net loss attributable to noncontrolling interests Net income attributable to Omega Earnings (loss) per share - Basic: Continuing operations attributable to Omega Discontinued operations attributable to Omega Basic Income per share attributable to Omega Earnings (loss) per share - Diluted: Continuing operations attributable to Omega Discontinued operations attributable to Omega Diluted income per share attributable to Omega Basic weighted average shares outstanding Diluted weighted average shares outstanding 654,399 415,386 355,548 157,686 181,297 22,913 219,927 (11,951) 3,755,191 955,858 2,884 (8,931) (1,588) 948,223 (419,136) 529,087 6,709 535,796 36,631 572,427 184,570 177,982 3,897,898 1,008,715 2,920 (11,864) (685) 999,086 (463,619) 535,467 (13,886) 521,581 31,421 553,002 666,255 (283,072) 383,183 33,823 417,006 5,672 422,678 3.24 4.01 0.24 0.04 3.73 (0.09) 3.64 3.48 4.05 3.22 4.00 3.71 0.23 0.04 (0.09) 3.62 3.45 121,607 122.357 4.04 141,269 141.750 151,955 152 906 2012 $ $ Note 6. Accounts Receivable, net as of August 31: (s in thousands) Student accounts receivable Less allowance for doubtful accounts Net student accounts receivable Other receivables Total accounts receivable, net 287,619 (107,230) 180,389 17,890 198,279 2011 324,324 (128,897) 195,427 20,140 215,567 Student accounts receivable is composed primarily of amounts due related to tuition and educational services. Our student receivables are not collateralized; however, credit risk is reduced as the amount owed by any individual student is small relative to the total student receivables and the customer base is geographically diverse. The following table summarizes the activity in allowance for doubtful accounts for the fiscal years 2012, 2011 and 2010: Year Ended August 31, (s in thousands) 2012 2011 2010 Beginning allowance for doubtful accounts 128,897 192,857 110,420 Provision for uncollectible accounts receivable 146,742 181,297 282,628 Write-offs, net of recoveries (168,409) (245,257) (200,191) Ending allowance for doubtful accounts $ 107,230 128,897 192,857 2010: 2013 is in these artis) Tuition and educational services revenue $4,124,629 Educational materials revente 294,499 Services revenue 56.981 Other reveme 33.192 Gross revenue Less: Discounts (255 964) Net revenue $ 4,253,337 Year Ended August 31. 2011 2010 97% $ 4,549,010 96 % $4,738,712 7 % 320.780 796 324.951 1 % 76 500 296 84 185 1 % 23,139 22,414 106 % 4.969,429 105 % 5.170,262 (258 380) (596 (263,649) 100 % $ 4,711,049 100 % S 4906,613 96 % 7% 2% - % 4.509.301 105 % (5)% 100 % Exhibit 5 2008-2010 University of Waterloo Cohort Student-Loan Default Rates 30 26.4 25 20 18.8 17.9 Default percentage 15 129 10 5 0 2008 (2-Y) 2009 (2-Yr.) 2009 (3-Yr. 2010 (2-Yr.) Since the 1970s, a bachelor's degree had become a more common requirement for employment in America's increasingly skill-based economy. While the U.S. college-age population increased by roughly 25 percent between 1970 and 2010, college enrollment grew by nearly 250 percent over the same period. In the coming decade, it is estimated that 60 percent of new jobs will require more than a high school diploma. One of the innovations that helped fulfill the growing demand for higher education was for-profit educational services companies. These companies primarily focused on employed learners who sought accredited degrees through programs that allowed flexibility around their work schedules. One of the most profitable companies in the for-profit education sector was Omega Group, best known for its largest subsidiary, the University of Waterloo. Omega Group Omega Group was one of the world's largest private education providers, offering both online and on-campus programs at the undergraduate, master's, and doctoral levels. Omega operated educational institutions in the United States, the United Kingdom, Mexico, and Chile, but its U.S.-based subsidiary, the University of Waterloo, represented approximately 91 percent of the company's net revenue in fiscal year 2012. Founded in 1976, by 2012, the University of Waterloo had grown to become the largest private university in the U.S., with an enrollment of over 350,000 students. Over 67 percent of students attending the University of Waterloo in 2012 were women, and approximately 50 percent were minorities. Omega's business model relied on low costs and a predictable inflow of revenues. It kept costs low by employing part-time and adjunct faculty as instructors, providing classroom facilities but no student housing and build ing a scalable online educational delivery system. The cost of tuition of the schools operated by Omega, however, remained relatively high when compared to other public colleges. For example, tuition cost for a Bachelor of Science in Business at the University of Waterloo was $74,500. The same degree at the University of Arizona cost $44,200. Federal Student Financial Aid Programs In addition to for-profit educational services companies, increased college enrollment was facilitated, at least in part, by the U.S. government's decision to support various grant, loan, and work- study programs to help students pay for tuition and other education-related expenses. These programs were administered by the Department of Education under legislative authority provided by Title IV of the 1965 Higher Education Act. The Department of Education was created in 1867 with the primary role of collecting information on schools to help establish effective school systems. Federal aid to higher education began in 1890 with the passage of the Second Morrill Act. The end of World War II, however, led to a significant expansion of federal support in this area. The 1944 GI Bill" authorized the Department of Education to provide financial assistance that would ultimately send almost 8 million World War II veterans to college. In the years that followed, additional federal student financial aid programs were established, such as Stafford Loans and Pell Grants. As the U.S. government became more actively involved in helping students pay for higher education, it established regulations to ensure that loans made to students were likely to be repaid. Specifically, any educational institution with a two-year cohort default rate greater than or equal to 40 percent in any given year or greater than or equal to 25 percent for three consecutive years would be ineligible to participate in Title IV programs. In addition to addressing concerns about student loan defaults, federal regulations also explicitly targeted for-profit educational services companies, focusing on their sources of revenue. For-profit educational services companies had been increasingly successful over time in securing a disproportionate share of federal funding for higher education. While for-profit schools accounted for only 10 percent of higher-education students during the 20092010 school year, they received 25 percent of available funding from the Department of Education. (See Exhibit 1 for the top 10 for-profit recipients of Title IV funding during the 2010-11 school year.) Funding from the Department of Education was limited to certain eligible institutions. One of the regulations in this area was the 90/10 rule, which stated that any for-profit educational institution would be ineligible to participate in Title IV programs, if for two consecutive fiscal years it derived more than 90 percent of its cash-basis revenue for eligible tuition and fees from Title IV programs. (Exhibit 2 provides historical information on 90/10 percentages for the University of Waterloo.) Accounting for Bad Debts Students at the University of Waterloo were typically billed on a course-by-course basis when they first attended a session. At the time of billing, Omega established a receivable account and a matching deferred-revenue account. Revenue was recognized on a straight-line basis over the length of the applicable course, which is generally 5 to 9 weeks, and deferred revenue was likewise reduced. Students who withdrew from a course were entitled to a partial refund, generally based on the portion of the course they did not attend. Refunds were recorded as a reduction in deferred revenue during the period that a student withdrew from a class. Students tended to finance their education through some combination of Title IV funding, state financial aid, military benefits, tuition assistance from employers, and personal means. Like other educational institutions, the University of Waterloo had no control over the amount of Title IV funding awarded to their students and billed the Department of Education directly so that receivables' collectability was virtually certain. On the other hand, when students paid personally, there was a possibility that receivables would not be collectible. To account for the issue of uncollectible receivables, Omega reduced its receivables, as they were generated, by setting up allowances for amounts expected to become uncollectible. These estimates were based on historical collection experience, current trends, and other relevant factors. For example, the company increased its allowance for doubtful accounts after a student withdrew from an educational program. When an actual write-off occurred, the receivable was removed from the balance sheet, and the allowance for doubtful accounts was correspondingly decreased. (See Exhibit 3 for Omega's fiscal year 2012 balance sheet and income statement, and Exhibit 4 for historical information on Omega revenues, receivables, allowances for receivables expected to become uncollectible, provisions incurred in different periods for potentially uncollectible receivables, and write-offs as they took place.) Signs of Trouble In the wake of the 20072009 financial crisis, many began to question the value of higher education. Skyrocketing tuition had grown by almost five times the rate of inflation since 1983 and had resulted in students taking on ever more debt. Toward the end of 2012, student-loan debt in the U.S. approached $1 trillion dollars. At the same time, diminished job prospects due to relatively weak economic conditions caused student-loan delinquencies to rise, with student loans accounting for a higher percentage of household debt over 90 days past due than credit cards, mortgages, auto loans, and home-equity loans. While many blamed the financial crisis for high student-loan default rates, others pointed to another culprit: for-profit higher education. Differences in student outcomes had emerged between for-profit and not-for-profit schools. The three-year student-loan default rate for the 20082009 cohort of students was 8 percent at private not- for-profit schools and 11 percent at public not-for-profit schools, but it was 23 percent at for-profit schools. Of students who enrolled in for-profit schools in 2008-2009, 54 percent left without a degree or certificate by mid-2010. The rates of loan defaults by students were closely related to the number of students leaving the institution with no degrees (See Exhibit 5 for historical information on two- and three-year student-loan default rates for the University of Waterloo). The Department of Education tracked the number of students who defaulted on their student loan, ie., the student failed to make payments within 3 years of entering repayment, which usually begun 6 months after leaving the program Schools were encouraged to institute various default management programs for students by The Department of Education. Omega Group, like many other institutions, contracted with the General Revenue Corporation (GRC) to "cure students who were approaching defaults. Internal documents of Omega indicated that nearly all cures were accomplished by putting students into temporary deferments or forbearances. The additional interest accrued during the forbearance period was added to the principal loan balance. Statistics like these helped corroborate stories of aggressive marketing tactics and deficient curricula that had dogged the for-profit higher-education industry for years. They also reinforced the negative reputation of for-profit educational services companies. Upon the release of a 2012 U.S. Senate report on the findings of a two-year investigation into the for-profit higher-education industry, Senator Tom Harkin (D-IA) commented, In this report, you will find overwhelming documentation of overpriced tuition, predatory recruiting practices, sky-high dropout rates, billions of taxpayer dollars spent on aggressive marketing and advertising, and companies gaming regulations to maximize profits. These practices are not the exceptionthey are the norm; they are systemic throughout the industry, with very few exceptions." For-profit educational services companies had long been a darling of Wall Street analysts, who pointed to factors such as robust growth, a strong business model with great margins, and solid balance - sheet metrics in their buy ratings. However, all of this began to change in 2009 as bad press and regulatory scrutiny took their toll, souring market participants on for-profit educational services Exhibit 1 Top 10 For-Profit Recipients of Title IV Funding during 20102011 School Year 6,000 5,037 5,000 4,000 $ in millions 3,000 2,000 1,274 1,108 1,145 847 919 1,000 745 564 610 659 0 Grand Canyon University Capella University Argosy University Walden University Strayer University ITT Technical Institute Kaplan University Ashford University Devry University University of Waterloo 100 90 88 86 86 82 84 80 69 70 64 62 60 52 49 48 Percentage 50 40 30 20 10 0 2000 2001 2002 2003 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 OMEGA GROUP, INC. AND SUBSIDIARIES: CONSOLIDATED BALANCE SHEETS As of August 31, 2012 2011 1,276,375 318,334 198,279 26,341 69,052 49,609 1,937,990 571,629 5,946 103,345 149,034 77,628 22,750 2,868,322 1,571,664 379,407 215,567 35,629 124,137 44,382 2,370,786 553,027 5,946 133,297 121,117 70,949 14,584 3,269,706 419,318 (in thousands) ASSETS: Current assets Cash and cash equivalents Restricted cash and cash equivalents Accounts receivable, net Prepaid taxes Deferred tax assets, current portion Other current assets Total current assets Property and equipment, net Marketable securities Goodwill Intangible assets, net Deferred tax assets, less current portion Other assets Total assets LIABILITIES AND SHAREHOLDERS' EQUITY: Current liabilities Short-term borrowings and current portion of long-term debt Accounts payable Student deposits Deferred revenue Accrued and other current liabilities Total current liabilities Long-term debt Deferred tax liabilities Other long-term liabilities Total liabilities Commitments and contingencies Shareholders' equity Preferred stock, no par value, 1,000 shares authorized; none issued Omega Group Class A nonvoting common stock, no par value,400,000 shares authorized; 188,007 issued as of August 31, 2012 and 2011, and 111,768 and 130,004 outstanding as of August 31, 2012 and 2011, respectively Omega Group Class B voting common stock, no par value, 3,000 shares authorized: 475 issued and outstanding as of August 31, 2012 and 2011 Additional paid-in capital Omega Group Class A treasury stock, at cost, 76,239 and 58,003 shares as of August 31, 2012 and 2011, respectively Retained earnings Accumulated other comprehensive loss Total Omegashareholders' equity Noncontrolling (deficit) interests Total equity Total liabilities and shareholders' equity 638,588 74,872 362,143 254,555 324,881 1,655,039 81,323 15,881 191,756 1,943,999 69,551 424,045 293,436 448,937 1,655,287 179,691 26,400 164,339 2,025,717 103 103 1 93,770 1 68,724 13,878,612) 4,743,150 (30,034) 928,378 (4,055) 924,323 2,868,322 (3,125,175) 4,320,472 (23,761) 1,240,364 3,625 1,243,989 3,269,706 OMEGA GROUP, INC. AND SUBSIDIARIES: CONSOLIDATED STATEMENTS OF INCOME 2012 4,253,337 Year Ended August 31, 2011 4,711,049 2010 4,906,613 1,759,986 1,720,059 622,848 466,358 301,116 142,337 282,628 1,800,569 663,442 383,935 344,300 177,804 146,742 38,695 16,788 4,725 3,577,000 676,337 1,187 (11,745) 476 (In thousands, except per share data) Net revenue Costs and expenses: Instructional and studentadvisory Marketing Admissions advisory General and administrative Depreciation and amortization Provision for uncollectible accounts receivable Restructuring and other charges Goodwill and other intangibles impairment Litigation charge (credit), net Total costs and expenses Operating income Interest income Interest expense Other, net Income from continuing operations before taxes Provision for income taxes Income from continuing operations Income from discontinued operations, net of tax Net income Net loss attributable to noncontrolling interests Net income attributable to Omega Earnings (loss) per share - Basic: Continuing operations attributable to Omega Discontinued operations attributable to Omega Basic Income per share attributable to Omega Earnings (loss) per share - Diluted: Continuing operations attributable to Omega Discontinued operations attributable to Omega Diluted income per share attributable to Omega Basic weighted average shares outstanding Diluted weighted average shares outstanding 654,399 415,386 355,548 157,686 181,297 22,913 219,927 (11,951) 3,755,191 955,858 2,884 (8,931) (1,588) 948,223 (419,136) 529,087 6,709 535,796 36,631 572,427 184,570 177,982 3,897,898 1,008,715 2,920 (11,864) (685) 999,086 (463,619) 535,467 (13,886) 521,581 31,421 553,002 666,255 (283,072) 383,183 33,823 417,006 5,672 422,678 3.24 4.01 0.24 0.04 3.73 (0.09) 3.64 3.48 4.05 3.22 4.00 3.71 0.23 0.04 (0.09) 3.62 3.45 121,607 122.357 4.04 141,269 141.750 151,955 152 906 2012 $ $ Note 6. Accounts Receivable, net as of August 31: (s in thousands) Student accounts receivable Less allowance for doubtful accounts Net student accounts receivable Other receivables Total accounts receivable, net 287,619 (107,230) 180,389 17,890 198,279 2011 324,324 (128,897) 195,427 20,140 215,567 Student accounts receivable is composed primarily of amounts due related to tuition and educational services. Our student receivables are not collateralized; however, credit risk is reduced as the amount owed by any individual student is small relative to the total student receivables and the customer base is geographically diverse. The following table summarizes the activity in allowance for doubtful accounts for the fiscal years 2012, 2011 and 2010: Year Ended August 31, (s in thousands) 2012 2011 2010 Beginning allowance for doubtful accounts 128,897 192,857 110,420 Provision for uncollectible accounts receivable 146,742 181,297 282,628 Write-offs, net of recoveries (168,409) (245,257) (200,191) Ending allowance for doubtful accounts $ 107,230 128,897 192,857 2010: 2013 is in these artis) Tuition and educational services revenue $4,124,629 Educational materials revente 294,499 Services revenue 56.981 Other reveme 33.192 Gross revenue Less: Discounts (255 964) Net revenue $ 4,253,337 Year Ended August 31. 2011 2010 97% $ 4,549,010 96 % $4,738,712 7 % 320.780 796 324.951 1 % 76 500 296 84 185 1 % 23,139 22,414 106 % 4.969,429 105 % 5.170,262 (258 380) (596 (263,649) 100 % $ 4,711,049 100 % S 4906,613 96 % 7% 2% - % 4.509.301 105 % (5)% 100 % Exhibit 5 2008-2010 University of Waterloo Cohort Student-Loan Default Rates 30 26.4 25 20 18.8 17.9 Default percentage 15 129 10 5 0 2008 (2-Y) 2009 (2-Yr.) 2009 (3-Yr. 2010 (2-Yr.)