Answered step by step

Verified Expert Solution

Question

1 Approved Answer

How do you match different types of distribution density to three different types of consumer goods (convenient goods, specialty goods, and shopping goods)? As defined

How do you match different types of distribution density to three different types of consumer goods (convenient goods, specialty goods, and shopping goods)?

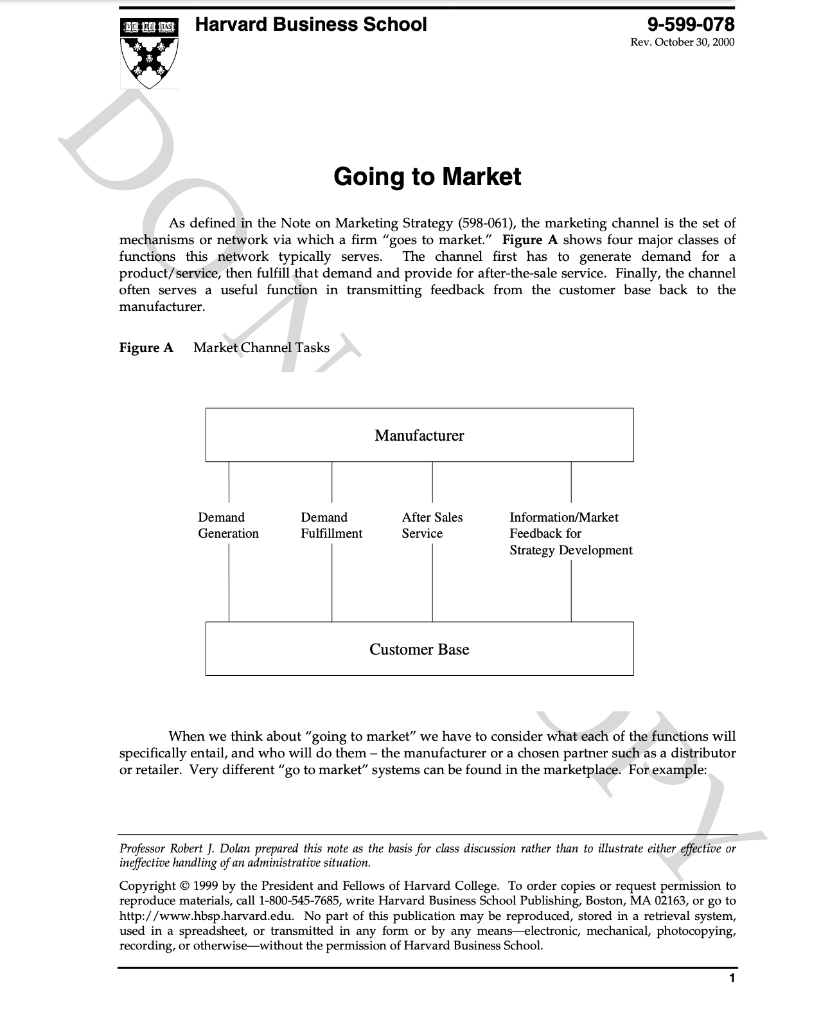

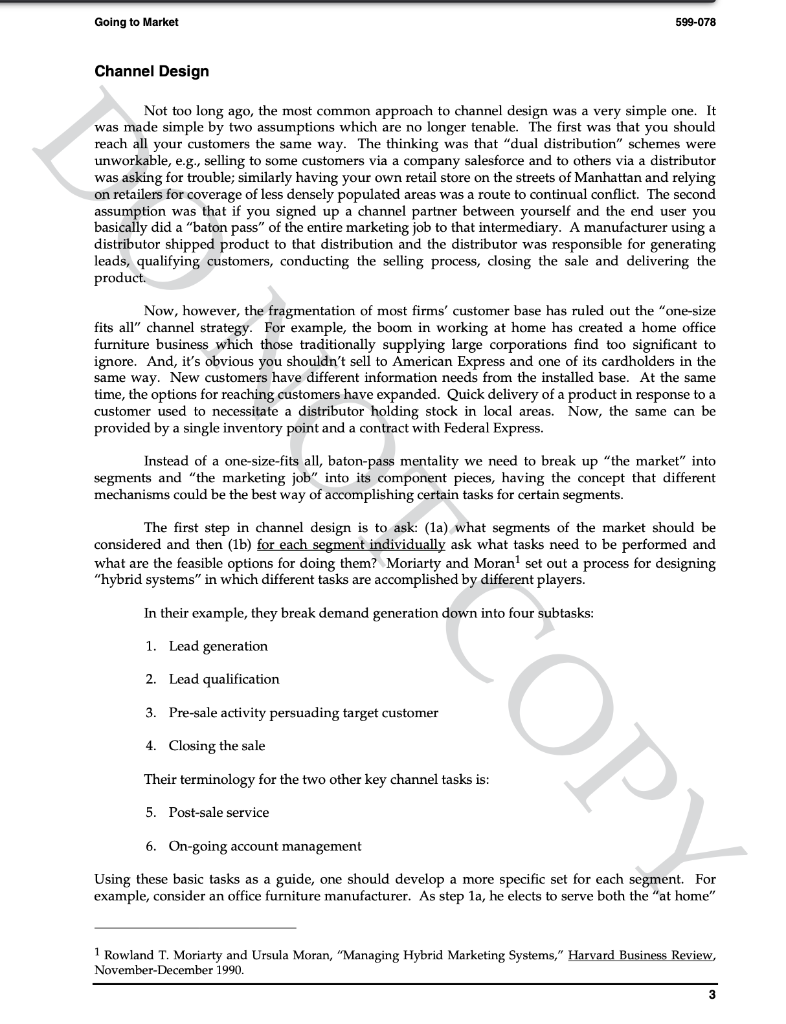

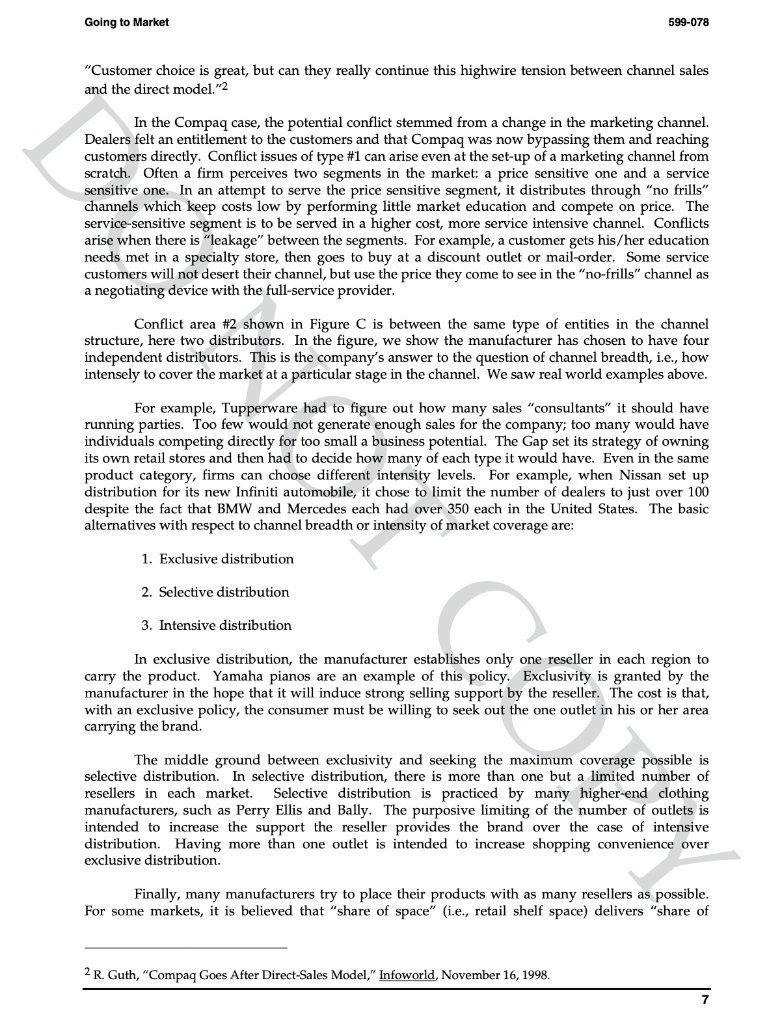

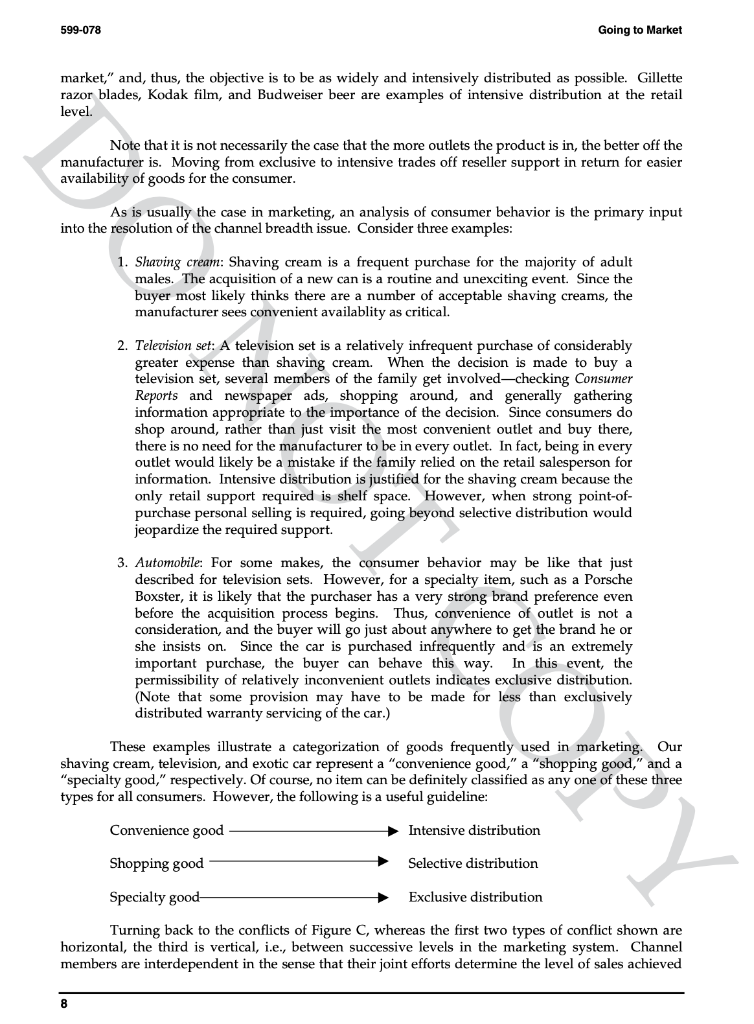

As defined in the Note on Marketing Strategy (598-061), the marketing channel is the set of mechanisms or network via which a firm "goes to market." Figure A shows four major classes of functions this network typically serves. The channel first has to generate demand for a product/service, then fulfill that demand and provide for after-the-sale service. Finally, the channel often serves a useful function in transmitting feedback from the customer base back to the manufacturer. Figure A Market Channel Tasks When we think about "going to market" we have to consider what each of the functions will specifically entail, and who will do them - the manufacturer or a chosen partner such as a distributor or retailer. Very different "go to market" systems can be found in the marketplace. For example: Professor Robert J. Dolan prepared this note as the basis for class discussion rather than to illustrate either effective or ineffective handling of an administrative situation. Copyright @ 1999 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College. To order copies or request permission to reproduce materials, call 1-800-545-7685, write Harvard Business School Publishing, Boston, MA 02163, or go to http://www.hbsp.harvard.edu. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, used in a spreadsheet, or transmitted in any form or by any means -electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise-without the permission of Harvard Business School. Knoll Furniture, a leading maker of high-end office furniture systems, uses its own salesforce to generate demand from large accounts. Demand fulfillment takes place through a dealer network. Avon Products generated $5 billion in sales in 1997 selling through 2.6 million sales representatives worldwide. Selling mostly cosmetics and fragrances, these reps are independent agents, not employees of Avon, who work part-time selling to female customers on a door-to-door basis. - Tupperware follows a similar direct selling model for its food storage containers, utilizing 950,000 independent Tupperware "consultants" worldwide. These consultants sell via the "party plan" in which potential customers gather at the home of a hostess for refreshments, product demonstration, and product ordering. - The Gap, Inc. designs all its own products which it sells through over 2,000 company-owned retail stores. It recently moved into electronic retailing opening the "Gap Online" store at www.gap.com. It outsources manufacturing, purchasing from 1200 suppliers, but manages the "going-to-market" phase entirely itself. - BMW, on the other hand, goes-to-market through partners, about 300 franchised dealers selling its automobiles in the United States. The dealers and BMW share responsibility for demand generation. BMW designs and implements national advertising. Dealers provide for product display and convenient testing by customers. Dealers fulfill demand, delivering vehicles to customers, and provide local after-the-sale service. - Compaq Computer sells primarily through third-party resellers. A systems integrator may obtain a Compaq computer and package it with other equipment to sell a system to a customer. Like the Gap, Compaq has recently added a direct on-line selling capability. Due to differences in the market situation, these manufacturers have seen fit to "go-tomarket" in different ways. The go-to-market approach may vary even within firm for different customer segments. The firm may choose "multiple channels." The Gap's set up of electronic store on the Web is an example of this strategy. The not-time-pressured customer who enjoys shopping visits the company store at the mall; while the time-pressured shopper visits the on-line store. A given individual may find a different channel more efficient depending on the buying occasion, e.g. a new sweater meriting a store visit, a simple blue jean replenishment order for a known size and style being best handle "on the Web." This note expands on the treatment of "Marketing Channels" in the Note on Marketing Strategy. As noted there, and suggested by these examples, the two key issues in "going to market" are (i) designing the network, i.e., who is on the team and what do we want each to do, and (ii) managing the network. In the short-term, this means figuring out how do we motivate each team member to do the desired tasks. In the longer term, it means how do we evolve and hold the system together in light of new products, evolution of the customer base (e.g., formation of buying groups) and new communication technologies such as the Internet. Going to Market 599-078 Channel Design Not too long ago, the most common approach to channel design was a very simple one. It was made simple by two assumptions which are no longer tenable. The first was that you should reach all your customers the same way. The thinking was that "dual distribution" schemes were unworkable, e.g., selling to some customers via a company salesforce and to others via a distributor was asking for trouble; similarly having your own retail store on the streets of Manhattan and relying on retailers for coverage of less densely populated areas was a route to continual conflict. The second assumption was that if you signed up a channel partner between yourself and the end user you basically did a "baton pass" of the entire marketing job to that intermediary. A manufacturer using a distributor shipped product to that distribution and the distributor was responsible for generating leads, qualifying customers, conducting the selling process, closing the sale and delivering the product. Now, however, the fragmentation of most firms' customer base has ruled out the "one-size fits all" channel strategy. For example, the boom in working at home has created a home office furniture business which those traditionally supplying large corporations find too significant to ignore. And, it's obvious you shouldn't sell to American Express and one of its cardholders in the same way. New customers have different information needs from the installed base. At the same time, the options for reaching customers have expanded. Quick delivery of a product in response to a customer used to necessitate a distributor holding stock in local areas. Now, the same can be provided by a single inventory point and a contract with Federal Express. Instead of a one-size-fits all, baton-pass mentality we need to break up "the market" into segments and "the marketing job" into its component pieces, having the concept that different mechanisms could be the best way of accomplishing certain tasks for certain segments. The first step in channel design is to ask: (1a) what segments of the market should be considered and then (1b) for each segment individually ask what tasks need to be performed and what are the feasible options for doing them? Moriarty and Moran 1 set out a process for designing "hybrid systems" in which different tasks are accomplished by different players. In their example, they break demand generation down into four subtasks: 1. Lead generation 2. Lead qualification 3. Pre-sale activity persuading target customer 4. Closing the sale Their terminology for the two other key channel tasks is: 5. Post-sale service 6. On-going account management Using these basic tasks as a guide, one should develop a more specific set for each segment. For example, consider an office furniture manufacturer. As step 1a, he elects to serve both the "at home" 1 Rowland T. Moriarty and Ursula Moran, "Managing Hybrid Marketing Systems," Harvard Business Review, November-December 1990. segment and the large corporate segment. Research shows the following about the tasks needed to be accomplished in "obtaining and maintaining" the "at home" buyer. Preliminary 1. Attract Attention as Potential Supplier 2. Position Company as Ergonomic Experts and One-Stop Shop for All needs (desk, chair, files, etc.) Moriarty and Moran suggest using "The Hybrid Grid" to support decision-making on how tasks should be accomplished. The grid, as shown Figure B, is a map of the tasks to be accomplished as the columns and the ways of possibly accomplishing the task as the rows. Each column has one " X Figure B The Hybrid Grid placed in it to show the mechanism via which the task moving the customer through the purchase process may be effected. At the start of the process, one should think expansively about the possible matrix rows, i.e., the options for providing for specific task accomplishment. For our furniture seller, for example, task Going to Market 599-078 \#4 "Demonstrate Products" may initially suggest the need for a customer visit to retail outlet. But, with new technology, perhaps an adequate "demonstration" could be done virtually on the Web. Or, if convinced of the power of an in-home demonstration, one could induce it by offering free delivery and return if the product is not satisfactory. Imagine that the best plan for accomplishing the eleven at home buyer tasks are as follows: In this model, the firm did not "pass the baton" of its marketing job to another entity. Rather it kept 9 of the 11 functions itself, and outsourced two: task 6 to Federal Express and task 11 to the credit card companies. Obviously, the approach for our furniture maker to serve a large corporate account moving into a new headquarters building would be quite different. The economics of a large order allow for different selling techniques, but more fundamentally the tasks which need to be accomplished are different, e.g., they might be: 1. Get On Short List For This Job (any account of this size would already be aware of company and its positioning vis--vis competitors) 2. Present the Product Line 3. Demonstrate Company Ability to Customize a Solution to Client's Needs 4. Work with Client's Architect/Designer to Specify Furniture Solution, including mock-up of Furniture at Customer Location 5. Negotiate Price/Terms 6. Facilitate Disposal of Old Furniture 7. Accept Order 8. Work with Other Vendors to Develop Installation Plan 9. Respond to Changes Made to Order from Time of Order to Delivery 10. Deliver and Install Systems 11. Maintain Systems 12. Sell Accessories and Additional Systems 13. Upgrade as New Products are Introduced 14. Extend Credit Again, the Hybrid Grid should be used to specify the possible mechanisms to accomplishing these tasks. This helps to show key handoffs and cooperations. For example, step 2 may be best achieved by a visit to the local dealer showroom. Then steps 37 are to be accomplished by the company salesperson without any dealer input. This example we have worked through is typical in the sense that the different segments have very different marketing systems set up to serve them. In the case here, the at-home buyer and large corporation are so different that the systems are unlikely to come into conflict with one another. They could, if the firm made the mistake of offering a lower price on an item on its Website for the "at home" buyer than it offered to the customer buying large quantities of the same item. But generally, this example's two segments seem to be distinct enough that the manner of servicing one would have little impact on the other. Such is not always the case however. Once the tentative assessments have been made at the segment level, they have to be rolled up into a system view for potential channel conflicts. As an example, Figure C depicts a marketing system in which the manufacturer has a multiple channel strategy, i.e., it "goes to market" through its own salesforce calling on large accounts and uses distributors to call on smaller accounts. Potential Conflict area \#1 is that between the company salesforce and distributors. A distributor may regard a potential account as rightfully his to serve and resent the loss in margin opportunity due to the company's serving the large customers directly. Figure C Three Types of Channel Conflict A specific example of this type of conflict in channels was Compaq's November 1998 decision to sell computers directly to small business customers via the Internet. The new Prosigna line was offered via the Compaq DirectPlus on-line service. Compaq was already selling through 44,000 dealers and described the addition of the direct channel for the segment as a melding of traditional sales channels and the Internet, offering customers a choice. However, one commentator noted "Customer choice is great, but can they really continue this highwire tension between channel sales and the direct model." In the Compaq case, the potential conflict stemmed from a change in the marketing channel. Dealers felt an entitlement to the customers and that Compaq was now bypassing them and reaching customers directly. Conflict issues of type \#1 can arise even at the set-up of a marketing channel from scratch. Often a firm perceives two segments in the market: a price sensitive one and a service sensitive one. In an attempt to serve the price sensitive segment, it distributes through "no frills" channels which keep costs low by performing little market education and compete on price. The service-sensitive segment is to be served in a higher cost, more service intensive channel. Conflicts arise when there is "leakage" between the segments. For example, a customer gets his/her education needs met in a specialty store, then goes to buy at a discount outlet or mail-order. Some service customers will not desert their channel, but use the price they come to see in the "no-frills" channel as a negotiating device with the full-service provider. Conflict area \#2 shown in Figure C is between the same type of entities in the channel structure, here two distributors. In the figure, we show the manufacturer has chosen to have four independent distributors. This is the company's answer to the question of channel breadth, i.e., how intensely to cover the market at a particular stage in the channel. We saw real world examples above. For example, Tupperware had to figure out how many sales "consultants" it should have running parties. Too few would not generate enough sales for the company; too many would have individuals competing directly for too small a business potential. The Gap set its strategy of owning its own retail stores and then had to decide how many of each type it would have. Even in the same product category, firms can choose different intensity levels. For example, when Nissan set up distribution for its new Infiniti automobile, it chose to limit the number of dealers to just over 100 despite the fact that BMW and Mercedes each had over 350 each in the United States. The basic alternatives with respect to channel breadth or intensity of market coverage are: 1. Exclusive distribution 2. Selective distribution 3. Intensive distribution In exclusive distribution, the manufacturer establishes only one reseller in each region to carry the product. Yamaha pianos are an example of this policy. Exclusivity is granted by the manufacturer in the hope that it will induce strong selling support by the reseller. The cost is that, with an exclusive policy, the consumer must be willing to seek out the one outlet in his or her area carrying the brand. The middle ground between exclusivity and seeking the maximum coverage possible is selective distribution. In selective distribution, there is more than one but a limited number of resellers in each market. Selective distribution is practiced by many higher-end clothing manufacturers, such as Perry Ellis and Bally. The purposive limiting of the number of outlets is intended to increase the support the reseller provides the brand over the case of intensive distribution. Having more than one outlet is intended to increase shopping convenience over exclusive distribution. Finally, many manufacturers try to place their products with as many resellers as possible. For some markets, it is believed that "share of space" (i.e., retail shelf space) delivers "share of 2 R. Guth, "Compaq Goes After Direct-Sales Model," Infoworld, November 16, 1998. 599-078 Going to Market market," and, thus, the objective is to be as widely and intensively distributed as possible. Gillette razor blades, Kodak film, and Budweiser beer are examples of intensive distribution at the retail level. Note that it is not necessarily the case that the more outlets the product is in, the better off the manufacturer is. Moving from exclusive to intensive trades off reseller support in return for easier availability of goods for the consumer. As is usually the case in marketing, an analysis of consumer behavior is the primary input into the resolution of the channel breadth issue. Consider three examples: 1. Shaving cream: Shaving cream is a frequent purchase for the majority of adult males. The acquisition of a new can is a routine and unexciting event. Since the buyer most likely thinks there are a number of acceptable shaving creams, the manufacturer sees convenient availablity as critical. 2. Television set: A television set is a relatively infrequent purchase of considerably greater expense than shaving cream. When the decision is made to buy a television set, several members of the family get involved-checking Consumer Reports and newspaper ads, shopping around, and generally gathering information appropriate to the importance of the decision. Since consumers do shop around, rather than just visit the most convenient outlet and buy there, there is no need for the manufacturer to be in every outlet. In fact, being in every outlet would likely be a mistake if the family relied on the retail salesperson for information. Intensive distribution is justified for the shaving cream because the only retail support required is shelf space. However, when strong point-ofpurchase personal selling is required, going beyond selective distribution would jeopardize the required support. 3. Automobile: For some makes, the consumer behavior may be like that just described for television sets. However, for a specialty item, such as a Porsche Boxster, it is likely that the purchaser has a very strong brand preference even before the acquisition process begins. Thus, convenience of outlet is not a consideration, and the buyer will go just about anywhere to get the brand he or she insists on. Since the car is purchased infrequently and is an extremely important purchase, the buyer can behave this way. In this event, the permissibility of relatively inconvenient outlets indicates exclusive distribution. (Note that some provision may have to be made for less than exclusively distributed warranty servicing of the car.) These examples illustrate a categorization of goods frequently used in marketing. Our shaving cream, television, and exotic car represent a "convenience good," a "shopping good," and a "specialty good," respectively. Of course, no item can be definitely classified as any one of these three types for all consumers. However, the following is a useful guideline: Turning back to the conflicts of Figure C, whereas the first two types of conflict shown are horizontal, the third is vertical, i.e., between successive levels in the marketing system. Channel members are interdependent in the sense that their joint efforts determine the level of sales achieved 8 Going to Market 599-078 for the product. Consequently, there is a natural incentive to cooperate. However, there is also an inherent stimulus to conflict. Each party would like to see the other "do more" to improve the sales situation. A distributor wishes the manufacturer would spend more on national advertising to set the stage better for the distributors' salesforce as it calls on customers. The manufacturer wishes that the distributor would invest in better training for the salesforce and outfit them with the state-of-theart selling tools. Researchers 3 have identified the major sources of conflict as parties' differences in: 1. Goals 2. Understanding of proper scope of activities 3. Perceptions of reality An obvious difference in goals between a manufacturer and a distributor is each is focused on its own sales not the other's. The manufacturer may see an opportunity to expand its sales by opening up a new channel like the Internet. The distributor sees this as cannibalizing sales it would otherwise make. A distributor typically incorporates the manufacturer's product with lines from other manufacturers. To suit the distributor's purpose, the line may take on a strategic role that does not serve the best interests of the manufacturer. These conflicts are natural occurrences between two business entities each trying to serve its stakeholders. Contracts can be set up to mitigate goal incompatibility problems. These might specifically address what each party will contribute to the joint effort, how the effort will be monitored, and the division of the system profits contingent upon inputs each party provided. The second related major source of conflict is differences in understanding about the scope of activity, viz. (a) the functions which each party will carry out and (b) the target population for whom they will perform these functions. For example, a distributor may see it as the company's job to open new accounts which are then turned over to the distributor for service; meanwhile, the company expects the distributor salesforce to be "cold calling" and can't understand why the customer list is not seeing new additions each month. A second key scope issue is the population served, defined either geographically or by account type. This is basically the issue of "who owns the account?" If a copier manufacturer serves the City of Boston direct (through its own salesforce) but has a distributor for outlying districts (e.g., Cambridge) whose account is Harvard Business School, physically located in Boston but part of Harvard University based in Cambridge? The hybrid grid model described earlier can be a useful mechanism for getting all channel partners to understand how the overall system is designed to work and their role in it. The third source of conflict is simple different perceptions of the reality of a situation. For example, the distributor with its salesforce "on-the-street" everyday may see the performance gap that has developed between the manufacturer's product and those of competitors in the eyes of customers. But, the manufacturer still believes it is delivering superior quality. As another example, the manufacturer, tracking unit sales, sees a downward trend while the distributor sees a rapidly declining overall market in which it has more than held market share for the manufacturer. Effective channel management requires recognition of these potential threats to the system's working as it should. Some issues can be avoided by carefully drawing up a specific understanding 3 L.W. Stern, A.I. El-Ansary, and A.T. Coughlan, Marketing Channels, 5* ed., Prentice-Hall, 1996. about roles, duties, performance measurement, and payoffs. The key is to have all members see the interdependence of system members and to arrange communications and contracts so that each party perceives a "fair" return to their value added to the system. Summary Marketing system design issues are critical and can be a source of competitive advantage. Some companies are, in fact, defined more by their marketing system than their products. For example, the innovation and phenomenal success of L'Eggs pantyhose was not so much in the product as in the distribution through supermarkets and drugstores with efficient display racks. A marketing system also needs to be examined for its adaptability to new market opportunities and new technologies. Because channels involve complex legal relationships, they can be difficult to adjust and flexibility should be a criterion in judging a proposed structureStep by Step Solution

There are 3 Steps involved in it

Step: 1

Get Instant Access to Expert-Tailored Solutions

See step-by-step solutions with expert insights and AI powered tools for academic success

Step: 2

Step: 3

Ace Your Homework with AI

Get the answers you need in no time with our AI-driven, step-by-step assistance

Get Started