Answered step by step

Verified Expert Solution

Question

1 Approved Answer

How have you and your family or community participated in health and healing practices that differ from or complement biomedicine and western, scientific medicine (Olmos

How have you and your family or community participated in health and healing practices that differ from or complement biomedicine and western, "scientific medicine" (Olmos and Paravisini-Gebert, 2011, pg. 110).

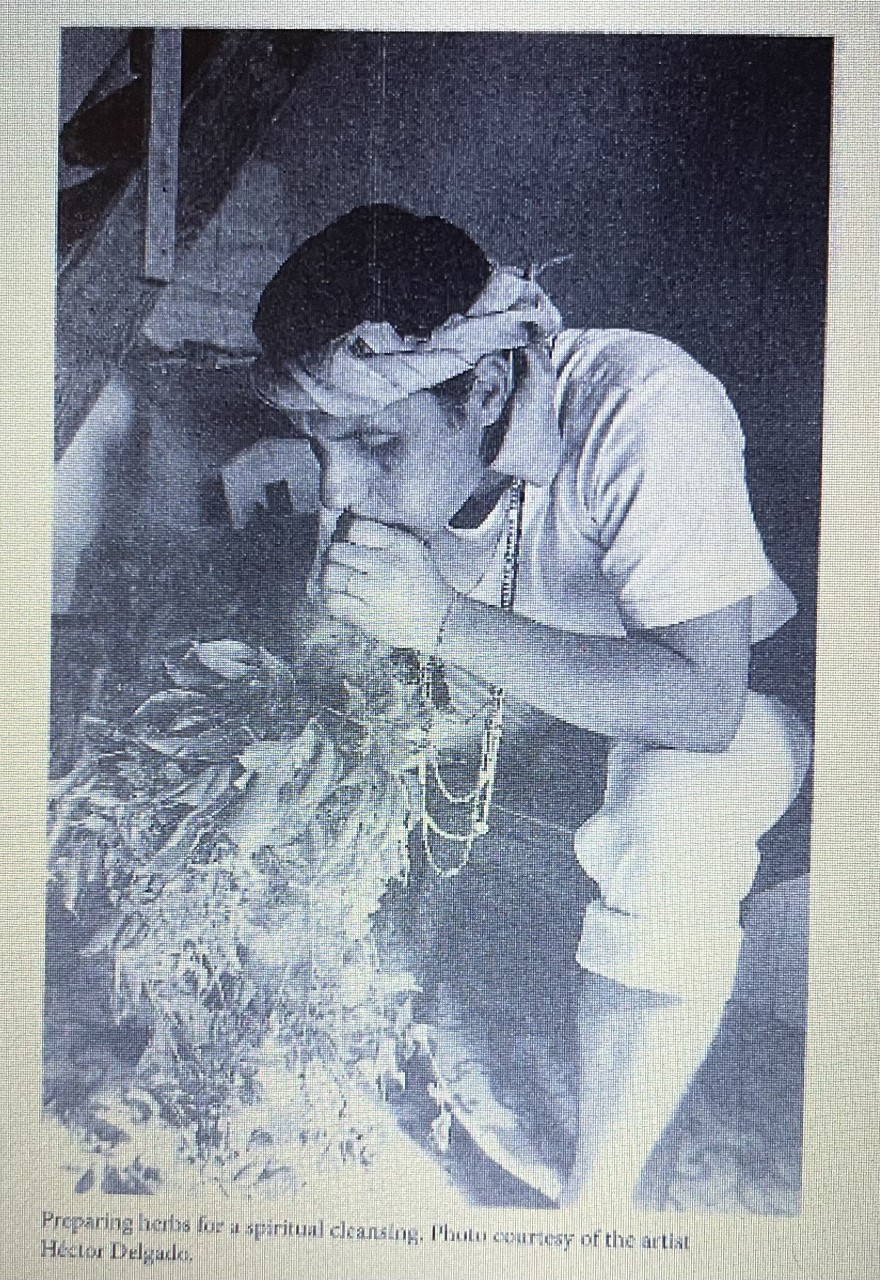

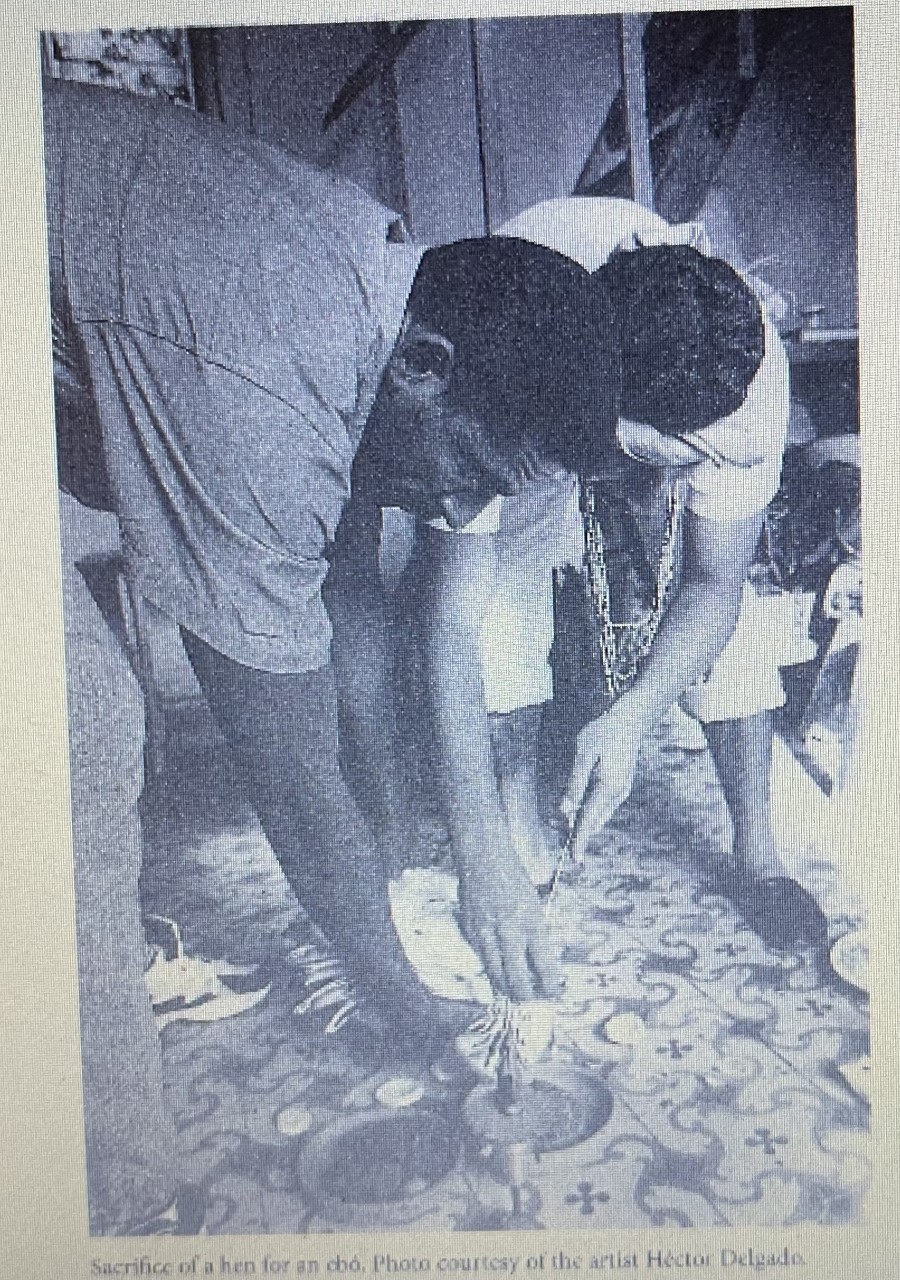

An Introduction from Vodou and Santeria to Obeah and Espiritismo SECONDEDITION 201 Margarite Fernndez Olmos and Lizabeth Paravisini-Gebert The Healing Traditions of Afro-Cubun Religions As with other Creole religions, Afro-Cuban practices are wide-ranging, influencing the arts, language, and virtually every aspect of Cuban culture. Healing, both physical and emotional, is no exception. Cuban anthropologist Lydia Cabrera and her Hailian counterpart Michel laguerre," among others, have written of the syncretic medical traditions of their respective cultures, folk practices not usually addressed in rescarch anchored in exclusively Western scientific conceptual categories. Although all healing practices originated in spiritual practices, boundaries gradually began to be erected between scientific medicine (symbolized by the germ theory of disease) and the supernatural. Although by the nineteenth century the process of desacralixing medicine appeared to be complete, in truth it was not. Faich healing and similar religious practices that consider faith a more effective cure than biomedicine experienced a revival in the 1980 s as part of a search for spiritual approaches to wellness: "It was Hippocrates who first bantshed spirits from the healing arts, and for the past 2,500 years the faithful hare struggled to force them back in" (Sides 1997: 94). In the Caribbean the spirits never left. An intrinsic part of the Amerindian world that later blended with the saints of the Roman Catholle colonist and the orishas and lwas of the African slave, they are a part of a syncretic healing system that is inclusive, pluralistic, local, and, in many cases, mag-cal The elements of Caribbean folk healing most rejected by mainstream culture-those that cannot withstand the scrutiny of scientific empirical investigation-are precisely the ones that claim the most tenacious hold on the Caribbean cultural imagination, namely, the magical, spiritual, religious methodologies of Santeria, Espiritismo, Vodou, Obeah, and the myriad other spiritual practices in the region and its. Diaspora. ("Root" and "hoodoo" doctors studied by Zora Neale Hurston and others in the southeastern United States are an example of the herbal-magical ethnomedical practices transplanted to the area from the Caribbean.) )27 Lydia Cabrera's brand of ethnobotany in her seminal work El monte is a case in point. The first half of the ethnographic work transcribes the belief systems of the Afm-Cuban peoples in the words of their followers-rituals, customs, and the magical causes of illness, legends, and traditions. In the second half Cabrera presents an extensive list of medicinal plants utilized by curanderos (faith-folk healers) classified by their local colloquial name in Cuba, the official Latin botanical nomenclaturc, and their spiritual name according to the appropriate Afro-Cuban religion: (L,) for the LukumiRegla de Ocha classification, and ( " C) for the Congo or Palo name, succceded by the plant's dueo or lord, that is, deity assoclated with it. Some entries are brief, with descriptions of their medical use, alternative names, and suggested medicinal recommendations, followed by a popular expression or anecdotal story related to Cabrera by one of her many informants. However, other entries are much more complex and detailed, with intricate rituals, historical background, and occasionally extensive stories surmounding the expcriences of an informant or the retelling of a Santeria pataki of the If divination 5y stem. Cabrera' brand of ethnobotany retlects the creolization process: established Western authoritative codes and hierarchies fuse in a fantastic synthesis and on equal footing with popular belief, personal anecdote, religgion, spirituality, indigennus and folk healing traditions, official and oral history, testimony, fiction, and fantasy, Not limited to one religion or knowledge tradition, Cahrera presents aeveral (L.ukumi, Palo, Abakua-anigo, and derivations of the same) from within the Afro-Cuban context that complement rather than compete with the Euro-Western elements of Ouben culture. Cabrera's 1984 study of Cuban healing systems, La medtcina popular en Cuba (Popular Medicine in Cuba), particularty chapter 4, "Black Folk Healers, documents the resilience of these bellef-healing practices." Their "divinely-inspired science" was based on fulfilling the required sacrifices or ebo to cure a malady. Each of the Afro-Cuban religions arrives at a diagnosis in its own fashion: Regla de Ocha practitioners determine the origin of a problem by questioning an orisha through possession or by means of one of the divination methods described in chapter 2; the Congo practitioner will communicate with the fumbi (the spirit of a deceased person) or a mpungu (a supernatural force) in his or her nganga who will speak and diagnose through trance, Anyone who has been around practitioners of the African religions in Cuba can appreciate the fact that sickness and dcath are not always attributable to natural causcs ... a curse can cat our lives short, as can the ire of an oricha when carelessness, disobedience, or unfulfillad promiscs incur its anger. Neglecting the deccased is yet another cause for suttering and death.... Despite their severity, the orishas ultimately come to the aid of their children and the faithful who beg them and offer gitts. A generous and timely ebb will appease them. (Fernndez Olmos, "Black Arts." 2001: 33). Afro-Cuban ethnomedical therapeutics is essentially plant-based: decoctions, infusions, aromatics, and/or baths arc prescribed to cleanse an evil spell or attract beneficent healing spirits. Some evil spells-bilongos, wembas, murumbas-are so powerful, however, that another sorcerer cannot undo them without risk to his own life. One of the more fascinating procedures used by practitioners of the Palo tradition is that of "switching lives." a practice that reflects the Congo belief in the ability to control a person's life spirit. tricking death. After consulting spiritually with the spirit of the dead of his or her nganga, the palero will dispense the treatment: We have heard of the wayombero seated on the floor next to the patient administering the brew he has prepired to "extract the witcherafl" and of the latter who drinks it and vomits feathers, stones, and huir. At that moment the sorcerer "swilches lives" [cambia vida]: he uses chalk, twine, 113 I Ajro-Cuban Religious Traditions a doll, or the stump of a plantain tree. He measures the patient and ties the doll or the stump with seven knots. With this procedure the evil that attacks the patient is transferred by the curandero onto the doll or stump, which is given the sick person's name, and thus death is tricked into believing that the buried stump or doll is the patient's cadaver.... A doll, we are told, properly baptized, is placed to sleep beside the sick person in his bed. The following day it is placed in a box, as if dead, and buried. The patient is cleansed three times with a rooster that is passed over the entire body. The rooster dies because it has absorbed the illness and is taken to a crossroad. The putienl then rests and undergoes a treatment of infusions. (Fernndez Olmos, "Black Arts", 2no1: 37-39) Folk healing modalities in the Caribbean region continue to become even more varied and complex due to migrations within the region and throughout the world, giving rise to new medical syncretisms and to a U.S. medi cal subculture. In Mlami, Puerto Ricans can be found buying folk spiritual remedies from Cubans, and Bahamians consult root doctors, for example. while in New York, Puerto Rican Spiritist healers treat Cuban patients, and Zuerto Ricans in turn consult Haitian folk healers (Laguerre 198 \&: 108-140). The aiternative and integrative strategies of adaptation and reinvention are embiematic of Creole healing modalities and have heen and will continue to :3 the tools of survival in resonrceful Carbbean societies

An Introduction from Vodou and Santeria to Obeah and Espiritismo SECONDEDITION 201 Margarite Fernndez Olmos and Lizabeth Paravisini-Gebert The Healing Traditions of Afro-Cubun Religions As with other Creole religions, Afro-Cuban practices are wide-ranging, influencing the arts, language, and virtually every aspect of Cuban culture. Healing, both physical and emotional, is no exception. Cuban anthropologist Lydia Cabrera and her Hailian counterpart Michel laguerre," among others, have written of the syncretic medical traditions of their respective cultures, folk practices not usually addressed in rescarch anchored in exclusively Western scientific conceptual categories. Although all healing practices originated in spiritual practices, boundaries gradually began to be erected between scientific medicine (symbolized by the germ theory of disease) and the supernatural. Although by the nineteenth century the process of desacralixing medicine appeared to be complete, in truth it was not. Faich healing and similar religious practices that consider faith a more effective cure than biomedicine experienced a revival in the 1980 s as part of a search for spiritual approaches to wellness: "It was Hippocrates who first bantshed spirits from the healing arts, and for the past 2,500 years the faithful hare struggled to force them back in" (Sides 1997: 94). In the Caribbean the spirits never left. An intrinsic part of the Amerindian world that later blended with the saints of the Roman Catholle colonist and the orishas and lwas of the African slave, they are a part of a syncretic healing system that is inclusive, pluralistic, local, and, in many cases, mag-cal The elements of Caribbean folk healing most rejected by mainstream culture-those that cannot withstand the scrutiny of scientific empirical investigation-are precisely the ones that claim the most tenacious hold on the Caribbean cultural imagination, namely, the magical, spiritual, religious methodologies of Santeria, Espiritismo, Vodou, Obeah, and the myriad other spiritual practices in the region and its. Diaspora. ("Root" and "hoodoo" doctors studied by Zora Neale Hurston and others in the southeastern United States are an example of the herbal-magical ethnomedical practices transplanted to the area from the Caribbean.) )27 Lydia Cabrera's brand of ethnobotany in her seminal work El monte is a case in point. The first half of the ethnographic work transcribes the belief systems of the Afm-Cuban peoples in the words of their followers-rituals, customs, and the magical causes of illness, legends, and traditions. In the second half Cabrera presents an extensive list of medicinal plants utilized by curanderos (faith-folk healers) classified by their local colloquial name in Cuba, the official Latin botanical nomenclaturc, and their spiritual name according to the appropriate Afro-Cuban religion: (L,) for the LukumiRegla de Ocha classification, and ( " C) for the Congo or Palo name, succceded by the plant's dueo or lord, that is, deity assoclated with it. Some entries are brief, with descriptions of their medical use, alternative names, and suggested medicinal recommendations, followed by a popular expression or anecdotal story related to Cabrera by one of her many informants. However, other entries are much more complex and detailed, with intricate rituals, historical background, and occasionally extensive stories surmounding the expcriences of an informant or the retelling of a Santeria pataki of the If divination 5y stem. Cabrera' brand of ethnobotany retlects the creolization process: established Western authoritative codes and hierarchies fuse in a fantastic synthesis and on equal footing with popular belief, personal anecdote, religgion, spirituality, indigennus and folk healing traditions, official and oral history, testimony, fiction, and fantasy, Not limited to one religion or knowledge tradition, Cahrera presents aeveral (L.ukumi, Palo, Abakua-anigo, and derivations of the same) from within the Afro-Cuban context that complement rather than compete with the Euro-Western elements of Ouben culture. Cabrera's 1984 study of Cuban healing systems, La medtcina popular en Cuba (Popular Medicine in Cuba), particularty chapter 4, "Black Folk Healers, documents the resilience of these bellef-healing practices." Their "divinely-inspired science" was based on fulfilling the required sacrifices or ebo to cure a malady. Each of the Afro-Cuban religions arrives at a diagnosis in its own fashion: Regla de Ocha practitioners determine the origin of a problem by questioning an orisha through possession or by means of one of the divination methods described in chapter 2; the Congo practitioner will communicate with the fumbi (the spirit of a deceased person) or a mpungu (a supernatural force) in his or her nganga who will speak and diagnose through trance, Anyone who has been around practitioners of the African religions in Cuba can appreciate the fact that sickness and dcath are not always attributable to natural causcs ... a curse can cat our lives short, as can the ire of an oricha when carelessness, disobedience, or unfulfillad promiscs incur its anger. Neglecting the deccased is yet another cause for suttering and death.... Despite their severity, the orishas ultimately come to the aid of their children and the faithful who beg them and offer gitts. A generous and timely ebb will appease them. (Fernndez Olmos, "Black Arts." 2001: 33). Afro-Cuban ethnomedical therapeutics is essentially plant-based: decoctions, infusions, aromatics, and/or baths arc prescribed to cleanse an evil spell or attract beneficent healing spirits. Some evil spells-bilongos, wembas, murumbas-are so powerful, however, that another sorcerer cannot undo them without risk to his own life. One of the more fascinating procedures used by practitioners of the Palo tradition is that of "switching lives." a practice that reflects the Congo belief in the ability to control a person's life spirit. tricking death. After consulting spiritually with the spirit of the dead of his or her nganga, the palero will dispense the treatment: We have heard of the wayombero seated on the floor next to the patient administering the brew he has prepired to "extract the witcherafl" and of the latter who drinks it and vomits feathers, stones, and huir. At that moment the sorcerer "swilches lives" [cambia vida]: he uses chalk, twine, 113 I Ajro-Cuban Religious Traditions a doll, or the stump of a plantain tree. He measures the patient and ties the doll or the stump with seven knots. With this procedure the evil that attacks the patient is transferred by the curandero onto the doll or stump, which is given the sick person's name, and thus death is tricked into believing that the buried stump or doll is the patient's cadaver.... A doll, we are told, properly baptized, is placed to sleep beside the sick person in his bed. The following day it is placed in a box, as if dead, and buried. The patient is cleansed three times with a rooster that is passed over the entire body. The rooster dies because it has absorbed the illness and is taken to a crossroad. The putienl then rests and undergoes a treatment of infusions. (Fernndez Olmos, "Black Arts", 2no1: 37-39) Folk healing modalities in the Caribbean region continue to become even more varied and complex due to migrations within the region and throughout the world, giving rise to new medical syncretisms and to a U.S. medi cal subculture. In Mlami, Puerto Ricans can be found buying folk spiritual remedies from Cubans, and Bahamians consult root doctors, for example. while in New York, Puerto Rican Spiritist healers treat Cuban patients, and Zuerto Ricans in turn consult Haitian folk healers (Laguerre 198 \&: 108-140). The aiternative and integrative strategies of adaptation and reinvention are embiematic of Creole healing modalities and have heen and will continue to :3 the tools of survival in resonrceful Carbbean societies Step by Step Solution

There are 3 Steps involved in it

Step: 1

Get Instant Access to Expert-Tailored Solutions

See step-by-step solutions with expert insights and AI powered tools for academic success

Step: 2

Step: 3

Ace Your Homework with AI

Get the answers you need in no time with our AI-driven, step-by-step assistance

Get Started