i just need some help figuring out how to find the answers in number 2 with all this given information.

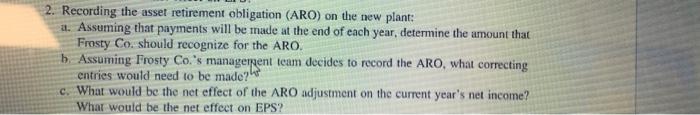

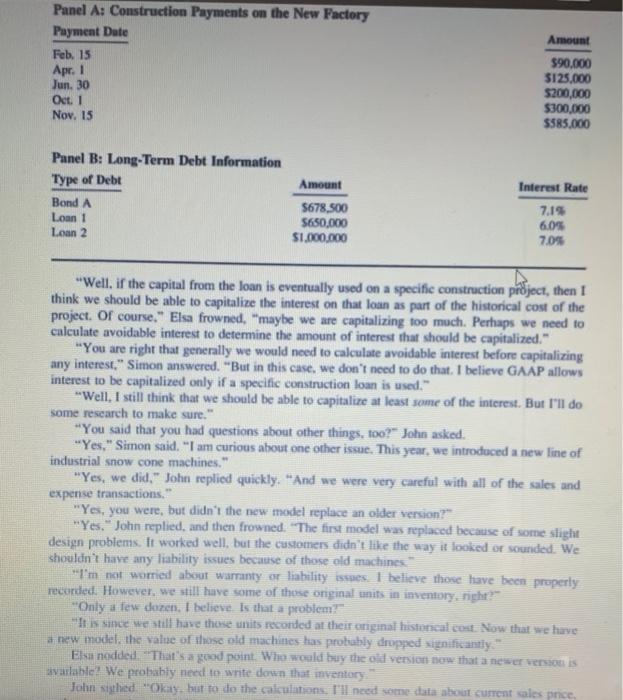

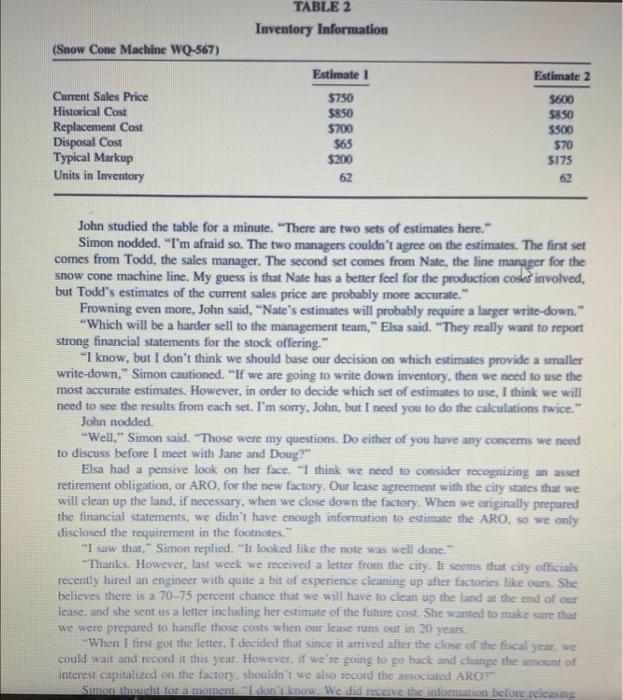

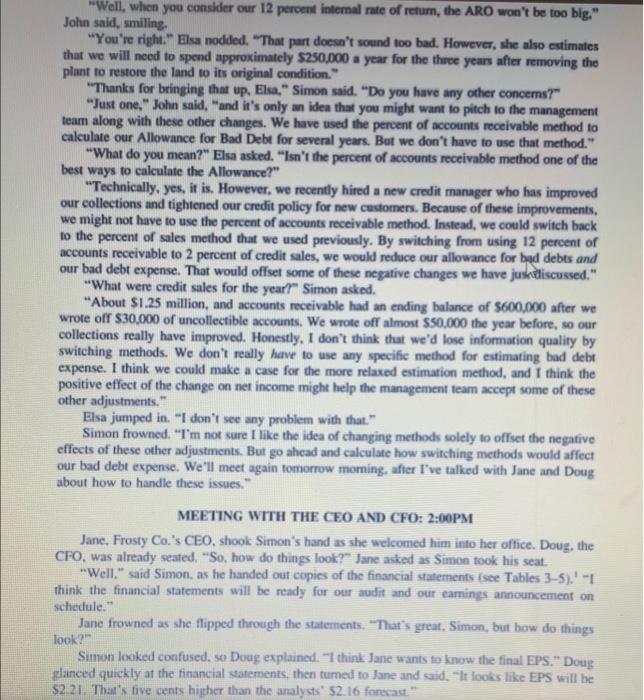

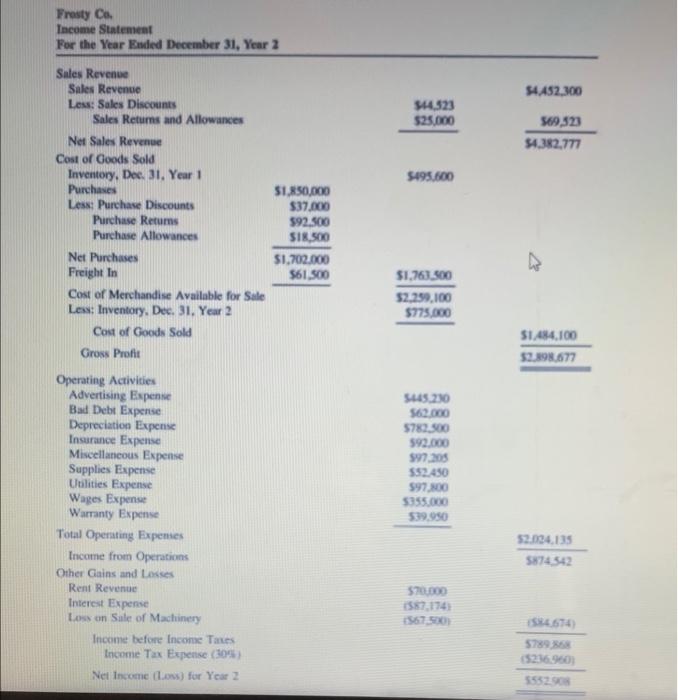

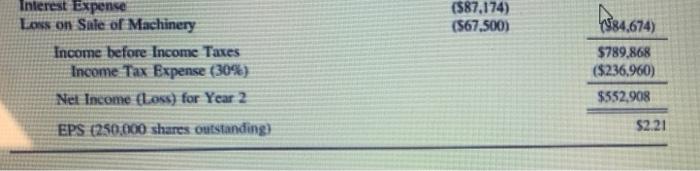

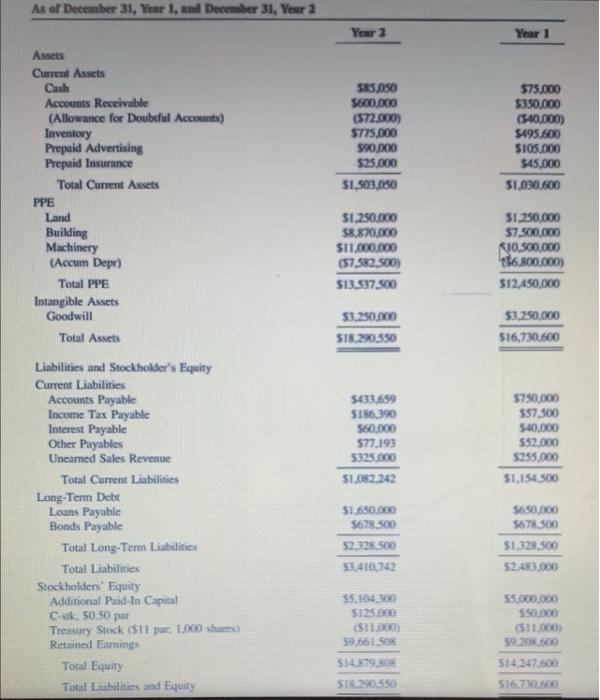

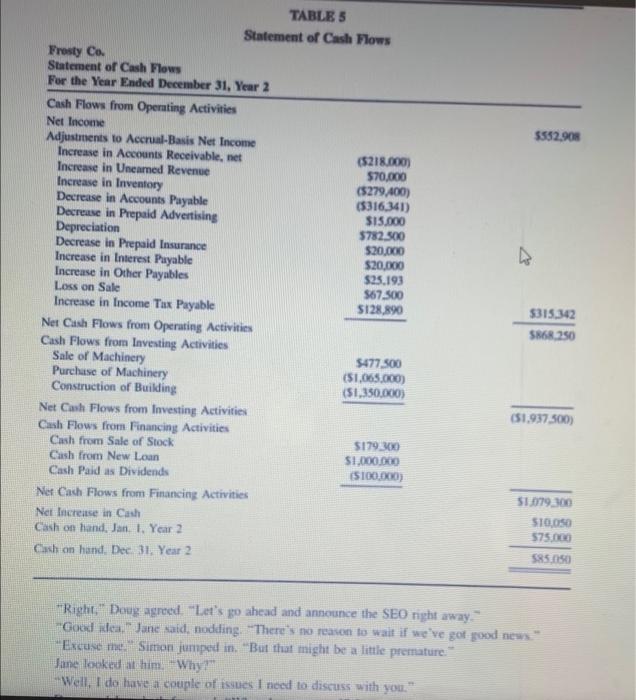

2. Recording the asset retirement obligation (ARO) on the new plant: a. Assuming that payments will be made at the end of each year, determine the amount that Frosty Co. should recognize for the ARO. b. Assuming Frosty Co.'s management team decides to record the ARO, what correcting entries would need to be made? c. What would be the net effect of the ARO adjustment on the current year's net income? What would be the net effect on EPS? Panel A: Construction Payments on the New Factory Payment Date Amount Feb. 15 $90,000 Apr. 1 Jun. 30 $125,000 $200,000 Oct. 1 $300,000 Nov. 15 $585,000 Panel B: Long-Term Debt Information Type of Debt Amount Interest Rate Bond A $678,500 7.1% Loan 1 6.0% Loan 2 $650,000 $1,000,000 7.0% "Well, if the capital from the loan is eventually used on a specific construction project, then I think we should be able to capitalize the interest on that loan as part of the historical cost of the project. Of course." Elsa frowned, "maybe we are capitalizing too much. Perhaps we need to calculate avoidable interest to determine the amount of interest that should be capitalized." "You are right that generally we would need to calculate avoidable interest before capitalizing any interest." Simon answered. "But in this case, we don't need to do that. I believe GAAP allows interest to be capitalized only if a specific construction loan is used." "Well, I still think that we should be able to capitalize at least some of the interest. But I'll do some research to make sure." "You said that you had questions about other things, too?" John asked. "Yes," Simon said. "I am curious about one other issue. This year, we introduced a new line of industrial snow cone machines." "Yes, we did." John replied quickly. "And we were very careful with all of the sales and expense transactions." "Yes, you were, but didn't the new model replace an older version?" "Yes." John replied, and then frowned. "The first model was replaced because of some slight design problems. It worked well, but the customers didn't like the way it looked or sounded. We shouldn't have any liability issues because of those old machines." "I'm not worried about warranty or liability issues. I believe those have been properly recorded. However, we still have some of those original units in inventory, right?" "Only a few dozen. I believe. Is that a problem?" "It is since we still have those units recorded at their original historical cost. Now that we have a new model, the value of those old machines has probably dropped significantly." Elsa nodded. "That's a good point. Who would buy the old version now that a newer version is available? We probably need to write down that inventory John sighed. "Okay, but to do the calculations. I'll need some data about current sales price, TABLE 2 Inventory Information (Snow Cone Machine WQ-567) Estimate 1 Estimate 2 $750 $600 $850 $8.50 Current Sales Price Historical Cost Replacement Cost Disposal Cost $700 $500 $65 $70 Typical Markup $200 $175 Units in Inventory 62 62 John studied the table for a minute. "There are two sets of estimates here." Simon nodded. "I'm afraid so. The two managers couldn't agree on the estimates. The first set comes from Todd, the sales manager. The second set comes from Nate, the line manager for the snow cone machine line. My guess is that Nate has a better feel for the production coses involved, but Todd's estimates of the current sales price are probably more accurate." Frowning even more, John said, "Nate's estimates will probably require a larger write-down." "Which will be a harder sell to the management team," Elsa said. "They really want to report strong financial statements for the stock offering." "I know, but I don't think we should base our decision on which estimates provide a smaller write-down." Simon cautioned. "If we are going to write down inventory, then we need to use the most accurate estimates. However, in order to decide which set of estimates to use, I think we will need to see the results from each set. I'm sorry, John, but I need you to do the calculations twice." John nodded. "Well," Simon said. "Those were my questions. Do either of you have any concerns we need to discuss before I meet with Jane and Doug?" Elsa had a pensive look on her face. "I think we need to consider recognizing an asset retirement obligation, or ARO, for the new factory. Our lease agreement with the city states that we will clean up the land, if necessary, when we close down the factory. When we originally prepared the financial statements, we didn't have enough information to estimate the ARO, so we only disclosed the requirement in the footnotes." "I saw that," Simon replied. "It looked like the note was well done. "Thanks. However, last week we received a letter from the city. It seems that city officials recently hired an engineer with quite a bit of experience cleaning up after factories like ours. She believes there is a 70-75 percent chance that we will have to clean up the land at the end of our lease, and she sent us a letter including her estimate of the future cost. She wanted to make sure that we were prepared to handle those costs when our lease runs out in 20 years. "When I first got the letter. I decided that since it arrived after the close of the fiscal year, we could wait and record it this year. However, if we're going to go back and change the amount of interest capitalized on the factory, shouldn't we also record the associated ARO?" Simon thought for a moment. I don't know. We did receive the information before releasing "Well, when you consider our 12 percent internal rate of return, the ARO won't be too big." John said, smiling. "You're right." Elsa nodded. "That part doesn't sound too bad. However, she also estimates that we will need to spend approximately $250,000 a year for the three years after removing the plant to restore the land to its original condition." "Thanks for bringing that up, Elsa." Simon said. "Do you have any other concerns?" "Just one," John said, "and it's only an idea that you might want to pitch to the management team along with these other changes. We have used the percent of accounts receivable method to calculate our Allowance for Bad Debt for several years. But we don't have to use that method." "What do you mean?" Elsa asked. "Isn't the percent of accounts receivable method one of the best ways to calculate the Allowance?" "Technically, yes, it is. However, we recently hired a new credit manager who has improved our collections and tightened our credit policy for new customers. Because of these improvements, we might not have to use the percent of accounts receivable method. Instead, we could switch back to the percent of sales method that we used previously. By switching from using 12 percent of accounts receivable to 2 percent of credit sales, we would reduce our allowance for bad debts and our bad debt expense. That would offset some of these negative changes we have jus discussed." "What were credit sales for the year?" Simon asked. "About $1.25 million, and accounts receivable had an ending balance of $600,000 after we wrote off $30,000 of uncollectible accounts. We wrote off almost $50,000 the year before, so our collections really have improved. Honestly, I don't think that we'd lose information quality by switching methods. We don't really have to use any specific method for estimating bad debt expense. I think we could make a case for the more relaxed estimation method, and I think the positive effect of the change on net income might help the management team accept some of these other adjustments." Elsa jumped in. "I don't see any problem with that." Simon frowned. "I'm not sure I like the idea of changing methods solely to offset the negative effects of these other adjustments. But go ahead and calculate how switching methods would affect our bad debt expense. We'll meet again tomorrow morning, after I've talked with Jane and Doug about how to handle these issues." MEETING WITH THE CEO AND CFO: 2:00PM Jane, Frosty Co.'s CEO, shook Simon's hand as she welcomed him into her office. Doug, the CFO, was already seated. "So, how do things look?" Jane asked as Simon took his seat. "Well," said Simon, as he handed out copies of the financial statements (see Tables 3-5). " think the financial statements will be ready for our audit and our earings announcement on schedule." Jane frowned as she flipped through the statements. "That's great, Simon, but how do things look?" Simon looked confused, so Doug explained. "I think Jane wants to know the final EPS." Doug glanced quickly at the financial statements, then turned to Jane and said, "It looks like EPS will be $2.21. That's five cents higher than the analysts' $2.16 forecast." Frosty Co. Income Statement For the Year Ended December 31, Year 2 Sales Revenue Sales Revenue Less: Sales Discounts Sales Returns and Allowances Net Sales Revenue Cost of Goods Sold Inventory, Dec. 31. Year 1 Purchases Less: Purchase Discounts Purchase Returns Purchase Allowances Net Purchases Freight In Cost of Merchandise Available for Sale Less: Inventory, Dec. 31. Year 2 Cost of Goods Sold Gross Profit Operating Activities Advertising Expense Bad Debt Expense Depreciation Expense Insurance Expense Miscellaneous Expense Supplies Expense Utilities Expense Wages Expense Warranty Expense Total Operating Expenses Income from Operations Other Gains and Losses Rent Revenue Interest Expense Loss on Sale of Machinery Income before Income Taxes Income Tax Expense (30%) Net Income (Loss) for Year 2 $1,850,000 $37,000 $92,500 $18,500 $1,702,000 $61,500 $44,523 $25,000 $495.600 $1,763.500 $2,259,100 $775,000 5445,230 $62,000 $782,500 $92,000 $97,205 $52,450 $97,800 $355,000 $39,950 $70,000 (587,174) $4,452,300 $69,523 $4,382,777 $1,484,100 $2.898.677 $2.024,135 $874,542 5789,868 ($236.960) $552.908 Interest Expense Loss on Sale of Machinery Income before Income Taxes Income Tax Expense (30%) Net Income (Loss) for Year 2 EPS (250,000 shares outstanding) ($87,174) ($67,500) ($84,674) $789,868 ($236,960) $552,908 $2.21 As of December 31, Year 1, and December 31, Year 2 Assets Current Assets Cash Accounts Receivable (Allowance for Doubtful Accounts) Inventory Prepaid Advertising Prepaid Insurance PPE Total Current Assets Land Building Machinery (Accum Depr) Total PPE Intangible Assets Goodwill Total Assets Liabilities and Stockholder's Equity Current Liabilities Accounts Payable Income Tax Payable Interest Payable Other Payables Uneamed Sales Revenue Total Current Liabilities Long-Term Debt Loans Payable Bonds Payable Total Long-Term Liabilities Total Liabilities Stockholders' Equity Additional Paid-In Capital C-stk, $0.50 par Treasury Stock ($11 par 1000 shares) Retained Earnings Total Equity Total Liabilities and Equity Year 2 $85,050 $600,000 ($72,000) $775,000 $90,000 $25,000 $1,503,050 $1,250,000 $8,870,000 $11,000,000 ($7,582,500) $13,537.500 $3,250,000 $18.290.550 $433,659 $186,390 $60,000 $77.193 $325,000 $1,082,242 $1,650,000 $678.500 $2.328.500 $3,410,742 $5,104.300 $125.000 ($11,000) $9,661,508 $14,879,808 $18.290.550 Year 1 $75,000 $350,000 ($40,000) $495,600 $105,000 $45,000 $1,030.600 $1,250,000 $7,500,000 10,500,000 6.800.000) $12,450,000 $3,250,000 $16,730,600 $750,000 $57,500 $40,000 $52,000 $255,000 $1,154,500 $650,000 $678.500 $1.328,500 $2,483,000 $5,000,000 $50,000 ($11,000) $9.208.600 $14,247.600 $16,730,600 TABLE 5 Statement of Cash Flows Frosty Co. Statement of Cash Flows For the Year Ended December 31, Year 2 Cash Flows from Operating Activities Net Income $552,908 Adjustments to Accrual-Basis Net Income Increase in Accounts Receivable, net Increase in Unearned Revenue Increase in Inventory ($218.000) $70,000 ($279,400) ($316,341) Decrease in Accounts Payable Decrease in Prepaid Advertising Depreciation $15,000 $782.500 $20,000 Decrease in Prepaid Insurance Increase in Interest Payable Increase in Other Payables Loss on Sale $20,000 $25.193 $67.500 Increase in Income Tax Payable $128,890 $315,342 Net Cash Flows from Operating Activities $868.250 Cash Flows from Investing Activities $477.500 Sale of Machinery Purchase of Machinery Construction of Building ($1,065.000) ($1,350,000) Net Cash Flows from Investing Activities ($1,937,500) Cash Flows from Financing Activities Cash from Sale of Stock $179.300 Cash from New Loan $1,000,000 Cash Paid as Dividends ($100,000) Net Cash Flows from Financing Activities $1.079.300 Net Increase in Cash $10,050 Cash on hand, Jan. 1. Year 2 $75,000 Cash on hand, Dec. 31, Year 2 $85,050 "Right," Doug agreed. "Let's go ahead and announce the SEO right away." "Good idea." Jane said, nodding. "There's no reason to wait if we've got good news" "Excuse me." Simon jumped in. "But that might be a little premature." Jane looked at him. "Why?" "Well, I do have a couple of issues I need to discuss with you." 2. Recording the asset retirement obligation (ARO) on the new plant: a. Assuming that payments will be made at the end of each year, determine the amount that Frosty Co. should recognize for the ARO. b. Assuming Frosty Co.'s management team decides to record the ARO, what correcting entries would need to be made? c. What would be the net effect of the ARO adjustment on the current year's net income? What would be the net effect on EPS? Panel A: Construction Payments on the New Factory Payment Date Amount Feb. 15 $90,000 Apr. 1 Jun. 30 $125,000 $200,000 Oct. 1 $300,000 Nov. 15 $585,000 Panel B: Long-Term Debt Information Type of Debt Amount Interest Rate Bond A $678,500 7.1% Loan 1 6.0% Loan 2 $650,000 $1,000,000 7.0% "Well, if the capital from the loan is eventually used on a specific construction project, then I think we should be able to capitalize the interest on that loan as part of the historical cost of the project. Of course." Elsa frowned, "maybe we are capitalizing too much. Perhaps we need to calculate avoidable interest to determine the amount of interest that should be capitalized." "You are right that generally we would need to calculate avoidable interest before capitalizing any interest." Simon answered. "But in this case, we don't need to do that. I believe GAAP allows interest to be capitalized only if a specific construction loan is used." "Well, I still think that we should be able to capitalize at least some of the interest. But I'll do some research to make sure." "You said that you had questions about other things, too?" John asked. "Yes," Simon said. "I am curious about one other issue. This year, we introduced a new line of industrial snow cone machines." "Yes, we did." John replied quickly. "And we were very careful with all of the sales and expense transactions." "Yes, you were, but didn't the new model replace an older version?" "Yes." John replied, and then frowned. "The first model was replaced because of some slight design problems. It worked well, but the customers didn't like the way it looked or sounded. We shouldn't have any liability issues because of those old machines." "I'm not worried about warranty or liability issues. I believe those have been properly recorded. However, we still have some of those original units in inventory, right?" "Only a few dozen. I believe. Is that a problem?" "It is since we still have those units recorded at their original historical cost. Now that we have a new model, the value of those old machines has probably dropped significantly." Elsa nodded. "That's a good point. Who would buy the old version now that a newer version is available? We probably need to write down that inventory John sighed. "Okay, but to do the calculations. I'll need some data about current sales price, TABLE 2 Inventory Information (Snow Cone Machine WQ-567) Estimate 1 Estimate 2 $750 $600 $850 $8.50 Current Sales Price Historical Cost Replacement Cost Disposal Cost $700 $500 $65 $70 Typical Markup $200 $175 Units in Inventory 62 62 John studied the table for a minute. "There are two sets of estimates here." Simon nodded. "I'm afraid so. The two managers couldn't agree on the estimates. The first set comes from Todd, the sales manager. The second set comes from Nate, the line manager for the snow cone machine line. My guess is that Nate has a better feel for the production coses involved, but Todd's estimates of the current sales price are probably more accurate." Frowning even more, John said, "Nate's estimates will probably require a larger write-down." "Which will be a harder sell to the management team," Elsa said. "They really want to report strong financial statements for the stock offering." "I know, but I don't think we should base our decision on which estimates provide a smaller write-down." Simon cautioned. "If we are going to write down inventory, then we need to use the most accurate estimates. However, in order to decide which set of estimates to use, I think we will need to see the results from each set. I'm sorry, John, but I need you to do the calculations twice." John nodded. "Well," Simon said. "Those were my questions. Do either of you have any concerns we need to discuss before I meet with Jane and Doug?" Elsa had a pensive look on her face. "I think we need to consider recognizing an asset retirement obligation, or ARO, for the new factory. Our lease agreement with the city states that we will clean up the land, if necessary, when we close down the factory. When we originally prepared the financial statements, we didn't have enough information to estimate the ARO, so we only disclosed the requirement in the footnotes." "I saw that," Simon replied. "It looked like the note was well done. "Thanks. However, last week we received a letter from the city. It seems that city officials recently hired an engineer with quite a bit of experience cleaning up after factories like ours. She believes there is a 70-75 percent chance that we will have to clean up the land at the end of our lease, and she sent us a letter including her estimate of the future cost. She wanted to make sure that we were prepared to handle those costs when our lease runs out in 20 years. "When I first got the letter. I decided that since it arrived after the close of the fiscal year, we could wait and record it this year. However, if we're going to go back and change the amount of interest capitalized on the factory, shouldn't we also record the associated ARO?" Simon thought for a moment. I don't know. We did receive the information before releasing "Well, when you consider our 12 percent internal rate of return, the ARO won't be too big." John said, smiling. "You're right." Elsa nodded. "That part doesn't sound too bad. However, she also estimates that we will need to spend approximately $250,000 a year for the three years after removing the plant to restore the land to its original condition." "Thanks for bringing that up, Elsa." Simon said. "Do you have any other concerns?" "Just one," John said, "and it's only an idea that you might want to pitch to the management team along with these other changes. We have used the percent of accounts receivable method to calculate our Allowance for Bad Debt for several years. But we don't have to use that method." "What do you mean?" Elsa asked. "Isn't the percent of accounts receivable method one of the best ways to calculate the Allowance?" "Technically, yes, it is. However, we recently hired a new credit manager who has improved our collections and tightened our credit policy for new customers. Because of these improvements, we might not have to use the percent of accounts receivable method. Instead, we could switch back to the percent of sales method that we used previously. By switching from using 12 percent of accounts receivable to 2 percent of credit sales, we would reduce our allowance for bad debts and our bad debt expense. That would offset some of these negative changes we have jus discussed." "What were credit sales for the year?" Simon asked. "About $1.25 million, and accounts receivable had an ending balance of $600,000 after we wrote off $30,000 of uncollectible accounts. We wrote off almost $50,000 the year before, so our collections really have improved. Honestly, I don't think that we'd lose information quality by switching methods. We don't really have to use any specific method for estimating bad debt expense. I think we could make a case for the more relaxed estimation method, and I think the positive effect of the change on net income might help the management team accept some of these other adjustments." Elsa jumped in. "I don't see any problem with that." Simon frowned. "I'm not sure I like the idea of changing methods solely to offset the negative effects of these other adjustments. But go ahead and calculate how switching methods would affect our bad debt expense. We'll meet again tomorrow morning, after I've talked with Jane and Doug about how to handle these issues." MEETING WITH THE CEO AND CFO: 2:00PM Jane, Frosty Co.'s CEO, shook Simon's hand as she welcomed him into her office. Doug, the CFO, was already seated. "So, how do things look?" Jane asked as Simon took his seat. "Well," said Simon, as he handed out copies of the financial statements (see Tables 3-5). " think the financial statements will be ready for our audit and our earings announcement on schedule." Jane frowned as she flipped through the statements. "That's great, Simon, but how do things look?" Simon looked confused, so Doug explained. "I think Jane wants to know the final EPS." Doug glanced quickly at the financial statements, then turned to Jane and said, "It looks like EPS will be $2.21. That's five cents higher than the analysts' $2.16 forecast." Frosty Co. Income Statement For the Year Ended December 31, Year 2 Sales Revenue Sales Revenue Less: Sales Discounts Sales Returns and Allowances Net Sales Revenue Cost of Goods Sold Inventory, Dec. 31. Year 1 Purchases Less: Purchase Discounts Purchase Returns Purchase Allowances Net Purchases Freight In Cost of Merchandise Available for Sale Less: Inventory, Dec. 31. Year 2 Cost of Goods Sold Gross Profit Operating Activities Advertising Expense Bad Debt Expense Depreciation Expense Insurance Expense Miscellaneous Expense Supplies Expense Utilities Expense Wages Expense Warranty Expense Total Operating Expenses Income from Operations Other Gains and Losses Rent Revenue Interest Expense Loss on Sale of Machinery Income before Income Taxes Income Tax Expense (30%) Net Income (Loss) for Year 2 $1,850,000 $37,000 $92,500 $18,500 $1,702,000 $61,500 $44,523 $25,000 $495.600 $1,763.500 $2,259,100 $775,000 5445,230 $62,000 $782,500 $92,000 $97,205 $52,450 $97,800 $355,000 $39,950 $70,000 (587,174) $4,452,300 $69,523 $4,382,777 $1,484,100 $2.898.677 $2.024,135 $874,542 5789,868 ($236.960) $552.908 Interest Expense Loss on Sale of Machinery Income before Income Taxes Income Tax Expense (30%) Net Income (Loss) for Year 2 EPS (250,000 shares outstanding) ($87,174) ($67,500) ($84,674) $789,868 ($236,960) $552,908 $2.21 As of December 31, Year 1, and December 31, Year 2 Assets Current Assets Cash Accounts Receivable (Allowance for Doubtful Accounts) Inventory Prepaid Advertising Prepaid Insurance PPE Total Current Assets Land Building Machinery (Accum Depr) Total PPE Intangible Assets Goodwill Total Assets Liabilities and Stockholder's Equity Current Liabilities Accounts Payable Income Tax Payable Interest Payable Other Payables Uneamed Sales Revenue Total Current Liabilities Long-Term Debt Loans Payable Bonds Payable Total Long-Term Liabilities Total Liabilities Stockholders' Equity Additional Paid-In Capital C-stk, $0.50 par Treasury Stock ($11 par 1000 shares) Retained Earnings Total Equity Total Liabilities and Equity Year 2 $85,050 $600,000 ($72,000) $775,000 $90,000 $25,000 $1,503,050 $1,250,000 $8,870,000 $11,000,000 ($7,582,500) $13,537.500 $3,250,000 $18.290.550 $433,659 $186,390 $60,000 $77.193 $325,000 $1,082,242 $1,650,000 $678.500 $2.328.500 $3,410,742 $5,104.300 $125.000 ($11,000) $9,661,508 $14,879,808 $18.290.550 Year 1 $75,000 $350,000 ($40,000) $495,600 $105,000 $45,000 $1,030.600 $1,250,000 $7,500,000 10,500,000 6.800.000) $12,450,000 $3,250,000 $16,730,600 $750,000 $57,500 $40,000 $52,000 $255,000 $1,154,500 $650,000 $678.500 $1.328,500 $2,483,000 $5,000,000 $50,000 ($11,000) $9.208.600 $14,247.600 $16,730,600 TABLE 5 Statement of Cash Flows Frosty Co. Statement of Cash Flows For the Year Ended December 31, Year 2 Cash Flows from Operating Activities Net Income $552,908 Adjustments to Accrual-Basis Net Income Increase in Accounts Receivable, net Increase in Unearned Revenue Increase in Inventory ($218.000) $70,000 ($279,400) ($316,341) Decrease in Accounts Payable Decrease in Prepaid Advertising Depreciation $15,000 $782.500 $20,000 Decrease in Prepaid Insurance Increase in Interest Payable Increase in Other Payables Loss on Sale $20,000 $25.193 $67.500 Increase in Income Tax Payable $128,890 $315,342 Net Cash Flows from Operating Activities $868.250 Cash Flows from Investing Activities $477.500 Sale of Machinery Purchase of Machinery Construction of Building ($1,065.000) ($1,350,000) Net Cash Flows from Investing Activities ($1,937,500) Cash Flows from Financing Activities Cash from Sale of Stock $179.300 Cash from New Loan $1,000,000 Cash Paid as Dividends ($100,000) Net Cash Flows from Financing Activities $1.079.300 Net Increase in Cash $10,050 Cash on hand, Jan. 1. Year 2 $75,000 Cash on hand, Dec. 31, Year 2 $85,050 "Right," Doug agreed. "Let's go ahead and announce the SEO right away." "Good idea." Jane said, nodding. "There's no reason to wait if we've got good news" "Excuse me." Simon jumped in. "But that might be a little premature." Jane looked at him. "Why?" "Well, I do have a couple of issues I need to discuss with you